History

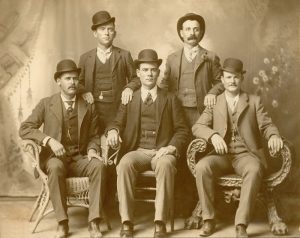

George “Bitter Creek” Newcomb was the first member of the infamous Dalton Gang…an outlaw gang in the Old West. Newcomb was born in 1866 near Fort Scott, Kansas. The Newcomb family was poor, and he began working as a cowboy at the age of twelve. Newcomb’s first job was on the “Long S Ranch” owned by CC Slaughter. By 1892, he had drifted into the Oklahoma Territory, where he first met Bill Doolin. Newcomb would meet up with Bill Doolin again, in a deadly way.

George “Bitter Creek” Newcomb was the first member of the infamous Dalton Gang…an outlaw gang in the Old West. Newcomb was born in 1866 near Fort Scott, Kansas. The Newcomb family was poor, and he began working as a cowboy at the age of twelve. Newcomb’s first job was on the “Long S Ranch” owned by CC Slaughter. By 1892, he had drifted into the Oklahoma Territory, where he first met Bill Doolin. Newcomb would meet up with Bill Doolin again, in a deadly way.

As a part of the Dalton Gang, Newcomb met up with Doolin and also met Charley Pierce, who were also members. The three men took part in the botched train robbery in Adair, Oklahoma Territory, on July 15, 1892. During the robbery, two guards and two townsmen, both doctors, were wounded. One of the doctors died the next day. Doolin, Newcomb, and Pierce complained that Bob was unfairly dividing the money fairly amongst the gang. They left in a huff, but later returned. It was at this point that Bob Dalton told Doolin, Newcomb, and Pierce that he no longer needed them. Dalton said that Newcomb was “too wild” for his gang, and Dalton left. Doolin and his friends returned to their hideout in Ingalls, Oklahoma Territory. On October 5, in Coffeyville, Kansas, the remaining members of the Dalton Gang were killed…except Emmett who survived despite being shot 27 times.  I suppose it was fortunate for Newcomb, Doolin, and Pierce that they were no longer part of the gang.

I suppose it was fortunate for Newcomb, Doolin, and Pierce that they were no longer part of the gang.

In 1893, Doolin organized his own gang from the remains of the original Dalton Gang, with Newcomb as a member, calling them the Wild Bunch. Bill Dalton later also joined the group and they became known as the Doolin-Dalton Gang. Newcomb began a romantic relationship with a 14 year old girl named Rose Dunn. She had four brothers who were outlaws and knew Newcomb. They would later become bounty hunters, calling themselves the Dunn Brothers. By 1895, Newcomb was a fugitive with a $5,000 reward on him, dead or alive. Rose Dunn traveled with him, since she could easily go into a town to purchase supplies, and no one knew that she was a part of the gang. This was the perfect plan to keep the gang hidden.

The gang often hung out in the town of Ingalls, Oklahoma. In those days, numerous outlaw gangs of the day took refuge there, and oddly, local residents often defended the outlaws and assisted in hiding them from lawmen. This was mostly due to the outlaws contributing greatly to the local economy. In one shootout with lawmen in Ingalls, called the Battle of Ingalls, three lawmen and three outlaws were shot. After several  shootouts with lawmen, Newcomb fled with outlaw Charley Pierce to a hideout near Norman, Oklahoma, both of them wounded in the Ingalls shootout with US Marshals.

shootouts with lawmen, Newcomb fled with outlaw Charley Pierce to a hideout near Norman, Oklahoma, both of them wounded in the Ingalls shootout with US Marshals.

On May 2, 1895, Newcomb and Pierce rode up to the Dunn ranch, possibly to visit Rose. As soon as they dismounted, her brothers opened fire, dropping both outlaws. The next day, the Dunn brothers had loaded the two bodies into their wagon and were driving it into town to collect the reward, when Newcomb suddenly moaned and asked for water, to which one of the brothers responded with another bullet. I guess the bounty on their heads outweighed the friendship the Dunn Brothers had previously with the Wild Bunch.

Casey, Illinois is a small town with just 2,635 people…as of 2018. Normally it would be considered a sleepy little town where nothing much happens, but Casey, Illinois is actually famous, and holds twelve world records. Yes, I said twelve!! That is a lot for a town of any size, and even more so for a town of only 2,635 people. Nevertheless, Casey has shown the world how it’s done.

Casey, Illinois is a small town with just 2,635 people…as of 2018. Normally it would be considered a sleepy little town where nothing much happens, but Casey, Illinois is actually famous, and holds twelve world records. Yes, I said twelve!! That is a lot for a town of any size, and even more so for a town of only 2,635 people. Nevertheless, Casey has shown the world how it’s done.

Their world’s record quest began with the Wind Chime in 2011. The framework for the Chime was assembled on site November 17, 2011. The huge wind chime features braces with Christian symbols. These add support, but more importantly they remind us of the importance of faith in our daily lives. The chimes were added to the frame on December 15, 2011. Many local residents attended the final touch on the structure, even though it was a cold day, it was also very exciting. With the world record the chime brought a new industry to the town…tourism. People like this sort of thing.

The next world record was the giant Golf Tee. This was suggested by the local Country Club president as a way of encouraging more interest in Casey’s public golf course. Work on the Tee in July of 2012. They team laminated lumber together to form the tee’s rough form. This took five months. Once the pieces of wood were secured, a chainsaw and sander were used to shape and smooth the surface. The Golf Tee claimed its “World’s Largest” status in May of 2013.

The Rocking Chair proved to be the most difficult World’s Record attempt. This behemoth of a project took two years to complete. The Chair claimed its world record title on October 20, 2015. In order to achieve the World’s Largest designation, the Rocking Chair needed to rock! This was quite a feat. It took ten grown men to accomplish this task! The headrest and armrests of the Chair include intricate carving and staining with a dove of peace featured on the center of the headrest and olive branches on the armrests.

In the years that followed, the wooden shoes (which can hold 15 people), the pitchfork, the mailbox (where you can actually mail a letter and go inside to do so), the key (an exact replica of the key for Jim Bolin’s work  truck), the gavel, the swizzle spoon, the golf driver, barber pole, and the teeter totter followed in quick succession…all earning world record status. There are many other “big” things that don’t have world record status, but are very cool, nevertheless. The big antlers, the big bird cage, the big softball bat, the big spinning top, the big toy glider, the big wooden token, the big pizza slicer, the big knitting needles and crochet hook, the big bookworm, the big nail puzzle, the big anvil and horseshoe, the big cactus, the big ear of corn, the big mouse trap, the big rocking horse, the big yardstick, the big pencil…all grace different areas of the town. I’m sure the idea was to be a unique town, and they have certainly achieved that status. While this might have started as a way to attract tourism, it proves one thing for sure…it is possible to be a little big town.

truck), the gavel, the swizzle spoon, the golf driver, barber pole, and the teeter totter followed in quick succession…all earning world record status. There are many other “big” things that don’t have world record status, but are very cool, nevertheless. The big antlers, the big bird cage, the big softball bat, the big spinning top, the big toy glider, the big wooden token, the big pizza slicer, the big knitting needles and crochet hook, the big bookworm, the big nail puzzle, the big anvil and horseshoe, the big cactus, the big ear of corn, the big mouse trap, the big rocking horse, the big yardstick, the big pencil…all grace different areas of the town. I’m sure the idea was to be a unique town, and they have certainly achieved that status. While this might have started as a way to attract tourism, it proves one thing for sure…it is possible to be a little big town.

Most of us have learned of the event that brought the United States into World War II…the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States was caught totally unaware, even though the signs were there, and even some chatter was heard. Nevertheless, our ships were sitting in the harbor, with many of the men not on board, and our planes were sitting on the tarmac. The plan the Japanese had was to wipe out the US military machine, so that the United States was virtually out of the war. The mistake the made was that they misjudged the United States. Nevertheless, on December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a battle the United States lost.

Most of us have learned of the event that brought the United States into World War II…the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States was caught totally unaware, even though the signs were there, and even some chatter was heard. Nevertheless, our ships were sitting in the harbor, with many of the men not on board, and our planes were sitting on the tarmac. The plan the Japanese had was to wipe out the US military machine, so that the United States was virtually out of the war. The mistake the made was that they misjudged the United States. Nevertheless, on December 7, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor was a battle the United States lost.

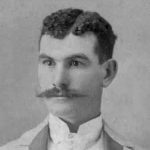

There were heroes on that day, however. The people who worked to save what lives they could, and put out the fires caused by the attack. And there were two heroes I had never heard about. I’m not sure why I hadn’t, but the fact remains that I hadn’t. Kenneth Taylor and George Welch were pilots stationed at Pearl Harbor on that fateful day. Taylor was a second lieutenant in the US Army Air Corps’ 47th Pursuit Squadron. He received his first posting to Wheeler Army Airfield in Honolulu, Hawaii in April 1941. His commanding officer, General Gordon Austin, chose Taylor and another pilot, George Welch, as his flight commanders shortly after they arrived in Hawaii. A week before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the 47th Pursuit Squadron was temporarily moved to the auxiliary airstrip at Haleiwa Field, located some 11 miles from Wheeler, for gunnery practice…a move that made their response to the attack possible.

Saturday, December 6, 1941, found Taylor and Welch spending the evening at a dance held at the officers’ club at Wheeler Field. After the dance, the two pilots joined an all-night poker game. After that, the account of the story gets a little fuzzy. Some said that the two pilots had finally gone to sleep, and were awoken only around 7:51am, when Japanese fighter planes and dive bombers attacked Wheeler, but others said that the poker game was just wrapping up, and they were contemplating a morning swim when the attack began. Whatever the case may be, Taylor and Welch were stunned to hear low-flying planes, explosions, and machine-gun fire above them. Information was scarce in all the chaos, but they learned that two-thirds of the planes at the main bases of Hickham and Wheeler Fields had been destroyed or damaged so badly that they were unable to fly. The two men rush to Haleiwa Field to get their planes. They had no orders, but Taylor called Haleiwa and  commanded the ground crew to prepare their Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks for takeoff, while Welch ran to get Taylor’s new Buick. The men were still wearing their tuxedo pants from the night before, but that didn’t stop them. The two pilots drove the 11 miles to Haleiwa, reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour along the way.

commanded the ground crew to prepare their Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks for takeoff, while Welch ran to get Taylor’s new Buick. The men were still wearing their tuxedo pants from the night before, but that didn’t stop them. The two pilots drove the 11 miles to Haleiwa, reaching speeds of 100 miles per hour along the way.

When they reached the field, Welch and Taylor jumped into their P-40s, which by that time had been fueled but not fully armed. That didn’t stop them. They took off and immediately attracted Japanese fire. Welch and Taylor were facing off virtually alone against some 200 to 300 enemy aircraft. When they ran out of ammunition, they returned to Wheeler to reload. The senior officers ordered the pilots to stay on the ground, but then

the second wave of Japanese raiders flew in, scattering the crowd. Taylor and Welch took off again, in the midst of a swarm of enemy planes. Though Welch’s machine guns were disconnected, he fired his .30-caliber guns, destroying two Japanese planes on the first attack run. On the second, with his plane heavily damaged by gunfire, he shot down two more enemy aircraft. A bullet pierced the canopy of Taylor’s plane, hitting his arm and sending shrapnel into his leg, but he managed to shoot down at least two Japanese planes, and perhaps more. In the end, Taylor was officially credited with two kills, and Welch with four.

Welch and Taylor were among only five Air Force pilots who managed to get their planes off the ground and engage the Japanese that morning. The total loss in aircraft at Pearl Harbor were estimated at 188 planes destroyed and 159 damaged. The Japanese lost just 29 planes. Both men were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross medals, becoming the first to be awarded that distinction in World War II. Welch was nominated for the Medal of Honor, the military’s highest award, but was reportedly denied because his superiors maintained he had taken off without proper authorization. For his injuries, Taylor received the Purple Heart.

After Pearl Harbor, George Welch flew nearly 350 missions in the Pacific Theater during World War II, shooting down 12 more planes and winning many other decorations. After he contracted malaria in 1943, his wartime career came to an end. While in the hospital in Sydney, Australia, he met his wife. After the war, Welch became a test pilot for North American Aviation. There are some claims that he became the first pilot to break the Mach-1 barrier with an unauthorized flight over the California desert in 1947, several weeks before Chuck Yeager’s famous flight. Unfortunately, Welch was killed in 1954 while ejecting from his disintegrating F-100 Super Sabre fighter jet during a test flight.

After Pearl Harbor, Ken Taylor was transferred to the South Pacific, where he flew out of Guadalcanal and was credited with downing another Japanese aircraft. Unfortunately, his combat career was cut short after someone fell on top of him in a trench during an air raid on the base, breaking his leg. He became a commander in the Alaska Air National Guard and retired as a brigadier general after 27 years of active duty. Taylor was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Legion of Merit, the Air Medal, and a number of other decorations. In his post military career, he worked as an insurance underwriter. Taylor died in Tucson, Arizona in 2006, at the age of 86.

Primo Levi was an Italian Jew born on July 31, 1919 at Corso Re Umberto 75 in Turin, Italy, to Jewish parents Cesare and Esther “Rina” Levi. His father worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Levi’s mother was well educated, having attended the Istituto Maria Letizia. Rina and Cesare’s marriage was arranged by Rina’s father, Cesare Luzzati, who gave the young couple the apartment at Corso Re Umberto as a wedding gift. Primo Levi lived there for almost his entire life.

Primo Levi was an Italian Jew born on July 31, 1919 at Corso Re Umberto 75 in Turin, Italy, to Jewish parents Cesare and Esther “Rina” Levi. His father worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Levi’s mother was well educated, having attended the Istituto Maria Letizia. Rina and Cesare’s marriage was arranged by Rina’s father, Cesare Luzzati, who gave the young couple the apartment at Corso Re Umberto as a wedding gift. Primo Levi lived there for almost his entire life.

Primo Levi was an intelligent young man who excelled in school. In September 1930 he entered the Massimo d’Azeglio Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the most clever…he was also the only Jew. All this brought as its reward constant bullying. In August 1932, following two years at the Talmud Torah school in Turin, he sang in the local synagogue for his Bar Mitzvah. In 1933, he joined the Avanguardisti movement for young Fascists, as was expected of all young Italian schoolboys. He never wanted to be a soldier, so he avoided rifle drill by joining the ski division, and spent every Saturday during the season on the slopes above Turin. As a young boy Levi was plagued by illness, particularly chest infections, but he was keen to participate in physical activity. In his teens, Levi and a few friends would sneak into a disused sports stadium and conduct athletic competitions.

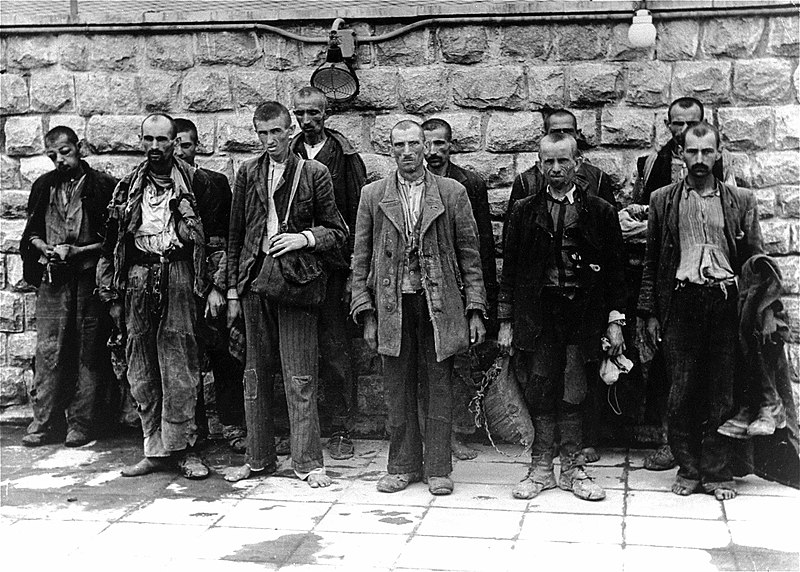

Levi later became a scientist, and it was this decision that would save his life during the Holocaust years…so to speak. When the deportations began, Levi found himself on a train to Auschwitz…the notorious death camp. The prisoners were put through a rigorous selection process. Those who didn’t make the cut, went directly to  the gas chambers. The rest were placed into forced labor…a harsh back-breaking labor with starvation level rations.

the gas chambers. The rest were placed into forced labor…a harsh back-breaking labor with starvation level rations.

Surviving the initial selection process at Auschwitz merely qualified a prisoner to be assigned to extremely harsh conditions involving back-breaking labor and intentionally miniscule amounts of nourishment. Levi was different. He was considered “useful” to the Nazis. His expertise as a scientist got him assigned in the camp laboratory. It also got him better food rations. Many would consider him lucky, but there was a price to pay for such luck. Levi was spared the horrific treatment his fellow prisoners were subjected to, but his protection from actually being subjected to such treatment did not save him from the horrors of witnessing such treatment. Levi tells the story of how prisoners at Auschwitz were treated in the books he has written on the subject. He tells of periodic selections, in which prisoners were forced to strip naked. These inspections were to “weed out” prisoners who were too exhausted or sick to provide meaningful labor. These prisoners were designated for transport to Auschwitz-Birkenau and the gas chamber. The prisoners who had been at Auschwitz…unlike newer prisoners, knew exactly what awaited them.

Levi’s description of this process from his work “The Drowned and the Saved” explains how most were already too mentally defeated and humiliated to resist: “The day in the [camp] was studded with innumerable harsh strippings – checking for lice, searching one’s clothes, examining for scabies and then the morning wash-up – as well as for the periodic selections, during which a ‘commission’ decided who was still fit for work and who, on the contrary, was marked for elimination. Now a naked and barefoot man feels that all his nerves and tendons are severed: He is helpless prey. Clothes, even the foul clothes distributed, even the crude clogs with their  wooden soles, are a tenuous but indispensable defense. Anyone who does not have them no longer perceives himself as a human being but rather as a worm: naked, slow, ignoble, prone on the ground. He knows that he can be crushed at any moment.”

wooden soles, are a tenuous but indispensable defense. Anyone who does not have them no longer perceives himself as a human being but rather as a worm: naked, slow, ignoble, prone on the ground. He knows that he can be crushed at any moment.”

Levi survived his ordeal in Auschwitz, one of the few that did, but that did not ensure a quiet peaceful life for him. On April 11, 1987, Primo Levi died after a fall from a three-story building. His death was ruled a suicide, which would not be surprising with “survivor’s guilt” syndrome, but there are many who don’t believe that Levi would have committed suicide, and they think his death was an accident. I don’t suppose we will ever know, but I believe that whatever happened, Primo Levi is finally at peace.

The atrocities the Nazis put the Jewish people and other minorities through in the camps, is well known to be horrible, but many people don’t know the half of it. Hitler had a number of camps in which to imprison these people that he had decided were “undesirable” for one reason or another. Some were even German people, who disagreed with Hitler’s ideas. They became the political prisoners. They were treated no better than their minority counterparts. Disagreeing with Hitler was a fatal choice for the most part.

The atrocities the Nazis put the Jewish people and other minorities through in the camps, is well known to be horrible, but many people don’t know the half of it. Hitler had a number of camps in which to imprison these people that he had decided were “undesirable” for one reason or another. Some were even German people, who disagreed with Hitler’s ideas. They became the political prisoners. They were treated no better than their minority counterparts. Disagreeing with Hitler was a fatal choice for the most part.

Mauthausen was the main political concentration camp in Austria. Mauthausen was not an extermination camp like Auschwitz-Birkenau. Nevertheless, it is estimated that about 100,000 people died at Mauthausen between its inception in 1939 and May 5, 1945, when it became the last camp liberated by the Allies. Sadly, like most of the camps, the liberation came just hours or days too late for some of the prisoners. These unfortunate ones died just prior to the liberation. Their strength gave out, just when rescue was so close.

Mauthausen was a little bit different than the other camps. Probably the greatest difference was the fact that the camp was in close proximity to a rock quarry. Near the quarry was a set of rock stairs known as the Stairs of Death. Most of us couldn’t imagine how a set of stairs could be considered such an instrument of death, that  they would become infamous, but that is exactly what these stairs did, and it is shocking. One of the survivors of Mauthausen gave this account saying, “Inmates were given light clothing and wooden (clogs) and put to work in the stone quarry. This involved carrying heavy stones up 180 steps, known as the “staircase of death” because of the beatings, shootings and fatal accidents to which the crowded mass of inmates was exposed to there. The food was totally inadequate for the heavy labor performed, and a stay in Mauthausen was indeed synonymous with “extermination by work.”

they would become infamous, but that is exactly what these stairs did, and it is shocking. One of the survivors of Mauthausen gave this account saying, “Inmates were given light clothing and wooden (clogs) and put to work in the stone quarry. This involved carrying heavy stones up 180 steps, known as the “staircase of death” because of the beatings, shootings and fatal accidents to which the crowded mass of inmates was exposed to there. The food was totally inadequate for the heavy labor performed, and a stay in Mauthausen was indeed synonymous with “extermination by work.”

Apparently, climbing the stone steps carrying heave stones was not the normal work performed at Mauthausen, but rather a deliberate punishment and death. The unfortunate prisoner or group of prisoners who made the guards angry, found out just how horrific this particular punishment was. One of the most famous incidents involved 47 Allied aviators transported to the camp. These men were essentially murdered in September 1944. Maurice Lampe, a French political prisoner, testified at Nuremberg saying, “For all the prisoners at Mauthausen, the murder of these men has remained in their minds like a scene from Dante’s Inferno. This is how it was done: at the bottom of the steps they loaded stones on the backs of these poor men and they had to carry  them to the top. The first journey was made with stones weighing 25 to 30 kilos (55 to 65 pounds) and was accompanied by blows. Then they were made to run down. For the second journey, the stones were even heavier; and whenever the poor wretches sank under their burden, they were kicked and hit with a bludgeon. Even stones were hurled at them… In the evening when I returned from the gang with which I was then working, the road which led to the camp was a bath of blood… I almost stepped on the lower jaw of a man. Twenty-one bodies were strewn along the road. Twenty-one had died on the first day. The twenty-six others died the following morning…”

them to the top. The first journey was made with stones weighing 25 to 30 kilos (55 to 65 pounds) and was accompanied by blows. Then they were made to run down. For the second journey, the stones were even heavier; and whenever the poor wretches sank under their burden, they were kicked and hit with a bludgeon. Even stones were hurled at them… In the evening when I returned from the gang with which I was then working, the road which led to the camp was a bath of blood… I almost stepped on the lower jaw of a man. Twenty-one bodies were strewn along the road. Twenty-one had died on the first day. The twenty-six others died the following morning…”

The sight of it was enough to make the description difficult for a man who had seen his share of horrific scenes in his lifetime. Anyone who had been in the camps, or through the camp, or involved in liberating the camps knew first hand the viciousness of the Nazi regime. Once they witnessed these atrocities, they could never forget what they saw. It was a scene that shaped them for the rest of their lives.

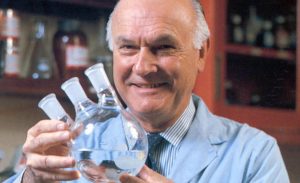

An inventor might set out to solve a problem or make a job easier, but halfway through the process…somehow, the invention turns into something completely different. And some inventions maybe started out simply experimenting with different chemicals and suddenly, you have something amazing.

An inventor might set out to solve a problem or make a job easier, but halfway through the process…somehow, the invention turns into something completely different. And some inventions maybe started out simply experimenting with different chemicals and suddenly, you have something amazing.

Eastman Kodak researcher, Harry Coover was trying to create plastic gunsights. Coover first came across cyanoacrylates (the chemical name for these überadhesives) in World War II. The problem was that the cyanoacrylates kept sticking to everything. The substance they came up with was very sticky. In fact, it was so sticky that it just wouldn’t work.  Its stickiness infuriated Coover. The substance was “shelved” for years, because while it was an interesting substance, they couldn’t figure out what to use it for.

Its stickiness infuriated Coover. The substance was “shelved” for years, because while it was an interesting substance, they couldn’t figure out what to use it for.

Coover dismissed the chemical and tried different approaches. He came across the material again in 1951. This time, Kodak experimented with cyanoacrylates for heat-resistant jet airplane canopies. Again, the stickiness got in the way. It wouldn’t work for the project at hand, but then Coover had an epiphany. “Coover realized these sticky adhesives had unique properties in that they required no heat or pressure to bond,” writes the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in a column from 2004. “He and his team tried the substance on various items in the lab and each time, the items became permanently bonded together. Coover – and his employer – knew they were on to something.” This stuff was an amazing adhesive.

While Coover’s original patent called the new invention “Superglue,” Kodak sold the adhesive under the less-evocative name “Eastman 910.” Have you ever heard of Eastman 910? No…I haven’t either. Sometimes the  success of an invention is partly or even largely in the name. Eastman 910 was a very good adhesive, but with a lackluster name. “Later it became known as Super Glue, and Coover became somewhat of a celebrity, appearing on television in the show ‘I’ve Got a Secret,’ where he lifted the host, Garry Moore, off the ground using a single drop of the substance,” writes MIT. I doubt there are many people these days who haven’t heard of Superglue. We have all used it, because it is one of the best glues out there. As the years go by, I’m sure inventors will come up with better glues, but I don’t know if any of them will be as easy to use as Superglue is.

success of an invention is partly or even largely in the name. Eastman 910 was a very good adhesive, but with a lackluster name. “Later it became known as Super Glue, and Coover became somewhat of a celebrity, appearing on television in the show ‘I’ve Got a Secret,’ where he lifted the host, Garry Moore, off the ground using a single drop of the substance,” writes MIT. I doubt there are many people these days who haven’t heard of Superglue. We have all used it, because it is one of the best glues out there. As the years go by, I’m sure inventors will come up with better glues, but I don’t know if any of them will be as easy to use as Superglue is.

As we all know, being a prisoner of war is not a safe place to be. Growing us watching shows like “Hogan’s Heroes” gave the impression that the enemy was always nice to their prisoners, and that being in a POW camp was ok, but that wasn’t the reality of those camps. Of course, in the days of “Hogan’s Heroes” violence was just not shown on television. The world was a different place…at least for the people back home watching it on television. The reality of the POW camps was much different, as many of us have seen in newer shows about prisoners during wars. We have witnessed some of the atrocities that have been done…and we still aren’t seeing the true story, I don’t suppose.

As we all know, being a prisoner of war is not a safe place to be. Growing us watching shows like “Hogan’s Heroes” gave the impression that the enemy was always nice to their prisoners, and that being in a POW camp was ok, but that wasn’t the reality of those camps. Of course, in the days of “Hogan’s Heroes” violence was just not shown on television. The world was a different place…at least for the people back home watching it on television. The reality of the POW camps was much different, as many of us have seen in newer shows about prisoners during wars. We have witnessed some of the atrocities that have been done…and we still aren’t seeing the true story, I don’t suppose.

One example of the true story is the Sandakan Death March. For some reason, when the Japanese were close to getting caught in their brutality, they decided that the best thing to do was to take the prisoners on a march deeper into the jungle so that the evidence of their torture was not found. In reality, they could have just left the prisoners in the camp…abandoned them, and they would have likely never been caught, but apparently it was more about retaliation over their loss in the war. One such march was the Bataan Death March in the Philippians and the deadly construction of the rail line linking Burma with Thailand.

Similar to that was the Sandakan Death March in Malaysia. It is not as well known, and in fact many Australians would like it to be removed from history…not from the history books, but they wish it had never happened at all. I can fully understand that, once I found out what the Sandakan Death March was all about. Still, I don’t understand why more people don’t know about it. There were 2,700 British and Australian prisoners of war interned there by Japanese forces, as the end of World War II  approached. The Sandakan Death March has been called that Australia’s worst military tragedy.

approached. The Sandakan Death March has been called that Australia’s worst military tragedy.

Sandakan was a brutal place. About 900 British soldiers were among the prisoners of war brought to Sandakan. Most of them did not survived. Prisoners interned here died slowly. They were starved and beaten. Toward the end of the war, when the Japanese decided to flee Sandakan, most of the remaining prisoners were marched to their deaths. Those who were strong enough to make it to the end of the trail were executed. Only six…a man named Owen Campbell and five others survived…and then only because they escaped. Campbell is the last living survivor, and a reminder that when war veterans pass away, a little piece of history dies with them. That is the saddest part of such horrific loss. When people forget about the atrocities of the past, the world is destined to repeat them. When life is viewed as so insignificant, then killing becomes easy, and the consequences of these killings is somehow pushed aside and even justified. That should never be allowed to happen…not in the POW camps, or in the streets of our cities. Bruce Scott, Australia’s minister for veterans affairs, referring to the prison guards at Sandakan said, “The proud and honorable title of soldier cannot be applied to those men.” The guards forced the prisoners to begin the death march from the camp at Sandakan as the Allies were approaching. The men were already very weak from being starved and beaten. Most of the men did not survive the march…succumbing to their conditions along the way. Those that survived the march were simply executed when they reached the end of the journey. That was even more brutal than the march itself.

Campbell returned to Borneo for a ceremony in March of 1999, back to the jungles where half a century ago his  best mates were marched to their deaths. Wearing a row of ribbons and medals across his left breast pocket, Mr. Campbell, aged 82, stared straight ahead at a black slab of granite, a memorial to one of the most horrific…yet little-known…atrocities of World War II in the Pacific. “We come here to this place to help ensure that this story is not forgotten,” Bruce Ruxton, an Australian veteran, told the crowd assembled at the memorial site. “We acknowledge that great evil was done here, that inhumanity here reached such depths that shame us as human beings even to contemplate.” In a sign of the continuing sensitivities and anger surrounding the prison camp and death march, no Japanese were present at the ceremony.

best mates were marched to their deaths. Wearing a row of ribbons and medals across his left breast pocket, Mr. Campbell, aged 82, stared straight ahead at a black slab of granite, a memorial to one of the most horrific…yet little-known…atrocities of World War II in the Pacific. “We come here to this place to help ensure that this story is not forgotten,” Bruce Ruxton, an Australian veteran, told the crowd assembled at the memorial site. “We acknowledge that great evil was done here, that inhumanity here reached such depths that shame us as human beings even to contemplate.” In a sign of the continuing sensitivities and anger surrounding the prison camp and death march, no Japanese were present at the ceremony.

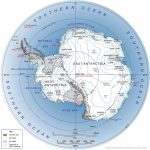

A military-free zone…is there such a place? Most of us don’t think so, but there is, actually. In reality, I can’t imagine fighting a war in Antarctica, but the area has actually been involved in a few disputes. Since the 1800s a number of nations, including Great Britain, Australia, Chile and Norway, have laid claim to parts of Antarctica. I think mostly the purpose for most nations is scientific research, but people have also taken trips across the frozen landscape as a way to challenge themselves. Of course, they didn’t do that in the 1800s.

A military-free zone…is there such a place? Most of us don’t think so, but there is, actually. In reality, I can’t imagine fighting a war in Antarctica, but the area has actually been involved in a few disputes. Since the 1800s a number of nations, including Great Britain, Australia, Chile and Norway, have laid claim to parts of Antarctica. I think mostly the purpose for most nations is scientific research, but people have also taken trips across the frozen landscape as a way to challenge themselves. Of course, they didn’t do that in the 1800s.

Over the years, the competing claims led to diplomatic disputes and even armed clashes. In 1948, Argentine military forces fired on British troops in an area claimed by both nations. Different nations, over the years have disputed lands and fought wars over ownership, and I guess that Antarctica was no different…even if I can’t imagine fighting over a frozen piece of land that, while it is 5,400,000 square miles of land, it is largely covered with ice and snow year round. Still, it seems to me that a continent that is that big would have plenty of room for everyone, but that did not settle the disputes.

Due to the increased number and type of incidents, together with evidence that the Soviet Union was becoming more interested in Antarctica, the United States decided to propose that the continent be made a trustee of the United Nations. This idea was rejected when none of the other nations with interests on the continent would agree to cede their claims of sovereignty to an international organization. That idea didn’t really go over too well either. By the 1950s, some officials in the United States began to press for a more active United States role in Antarctica, believing that the continent might have military potential as an area for nuclear tests. It looked like something was going to have to be done. President Dwight D Eisenhower took a different approach. US diplomats, working with their Soviet counterparts, worked out a treaty that set aside Antarctica as a military-free zone and postponed settling territorial claims for future debate. There could be “no military presence on the continent, and no testing of weapons of any sort, including nuclear weapons. Scientific ventures were allowed, and scientists would not be prohibited from traveling through any of the areas claimed by various nations.” Since the treaty did not directly tamper with issues of territorial sovereignty in Antarctica, the involved

parties included all nations with territorial claims on the continent. As such, the treaty marked a small but significant first step toward US-Soviet arms control and political cooperation. On December 1, 1959, twelve nations, including the United States and the Soviet Union, sign the Antarctica Treaty, which bans military activity and weapons testing on that continent. It was the first arms control agreement signed in the Cold War period. The treaty went into effect in June 1961, and its policies continue to govern Antarctica to this day.

parties included all nations with territorial claims on the continent. As such, the treaty marked a small but significant first step toward US-Soviet arms control and political cooperation. On December 1, 1959, twelve nations, including the United States and the Soviet Union, sign the Antarctica Treaty, which bans military activity and weapons testing on that continent. It was the first arms control agreement signed in the Cold War period. The treaty went into effect in June 1961, and its policies continue to govern Antarctica to this day.

I read an article recently, that I can’t get out of my head. “A Study Finds 66% Of US Millennials Can’t Identify What Auschwitz Is” talks about the movement to remove certain elements from world history. The picture of Auschwitz is as foreign to kids these days as the idea of “The Final Solution” was prior to Hitler’s reign of terror in Germany and parts of Europe which led to the Holocaust. The thing that shocks me most is that when they were asked, after a tour of Auschwitz, which is located in Poland, why they didn’t tear these horrible buildings down, they responded, “Oh no!! We leave them up so that we will never forget what happened here, and never allow it to happen again.” Wise words, and words that more people would do well to remember today.

I read an article recently, that I can’t get out of my head. “A Study Finds 66% Of US Millennials Can’t Identify What Auschwitz Is” talks about the movement to remove certain elements from world history. The picture of Auschwitz is as foreign to kids these days as the idea of “The Final Solution” was prior to Hitler’s reign of terror in Germany and parts of Europe which led to the Holocaust. The thing that shocks me most is that when they were asked, after a tour of Auschwitz, which is located in Poland, why they didn’t tear these horrible buildings down, they responded, “Oh no!! We leave them up so that we will never forget what happened here, and never allow it to happen again.” Wise words, and words that more people would do well to remember today.

During the past year, we have seen unrest, protests, riots, and the “cancel culture” that has become almost the norm of our time. The schools don’t teach parts of history anymore, in an act of Historical Negationism or denialism. This is not about revising history based on new information that would correct history. Usually, the purpose of historical negation is to achieve a national, political aim, by transferring war-guilt, demonizing an enemy, providing an illusion of victory, or preserving a friendship. Sometimes the purpose of a revised history is to sell more books or to attract attention with a newspaper headline. The historian James M. McPherson said that negationists would want revisionist history understood as, “a consciously-falsified or distorted interpretation of the past to serve partisan or ideological purposes in the present” All of that sounds an awful lot like what we have going on today.

Couple Historical Negationism with “taking offence” or “political correctness” and you have a recipe for disaster. In many of the riots of recent days, the rioters have torn down our historical statues. To me, it doesn’t matter if they think the statue portrays someone they find offensive, or not. That person is a pert of history, good, bad, or ugly. A hero of the South, might not be a hero of the North, but to those in the South he or she might have been. Was a war hero from Germany any less a war hero to his countrymen, simply because he was forced to fight on the side of the Nazis? I don’t think so. In fact many of the German soldiers had no idea of what was happening in their own country. I’m not standing up for the rightness, nor against the wrongness of the people

portrayed in the statues, but rather against the destruction of property. The buildings destroyed in the riots, the statues destroyed by the mobs, the looting that took place, all deemed “okay” because these places had insurance…does not make these vicious acts acceptable, or their perpetrators blameless. It’s time that we teach our children about patriotism, respect, fairness, and decency. If we don’t, we are going to find ourselves in the middle of a country that is destroyed by violence and hate. Wake up America!!

portrayed in the statues, but rather against the destruction of property. The buildings destroyed in the riots, the statues destroyed by the mobs, the looting that took place, all deemed “okay” because these places had insurance…does not make these vicious acts acceptable, or their perpetrators blameless. It’s time that we teach our children about patriotism, respect, fairness, and decency. If we don’t, we are going to find ourselves in the middle of a country that is destroyed by violence and hate. Wake up America!!

These days, we have advance warnings about potentially dangerous storms heading our way. Of course, the meteorologists aren’t always right on with their predictions, but often they are incredibly accurate. In centuries gone by, it was often the elder men, the ones who had been around a while, who had watched the sky, to see the signs that would give them clues as to coming weather. Unfortunately, on November 14, 1703, any clues they might have seen would not do any good for the people of England. The unusual weather began that day with strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean that battered the southern part of Britain and Wales. The pounding winds damaged many homes and other buildings, but the hurricane-like storm only began doing serious damage on November 26. Then the winds estimated at over 80 miles per hour, blew bricks from some buildings and embedded them in others. Wood beams, separated from buildings, flew through the air and killed hundreds across the south of the country. Towns such as Plymouth, Hull, Cowes, Portsmouth, and Bristol were devastated.

These days, we have advance warnings about potentially dangerous storms heading our way. Of course, the meteorologists aren’t always right on with their predictions, but often they are incredibly accurate. In centuries gone by, it was often the elder men, the ones who had been around a while, who had watched the sky, to see the signs that would give them clues as to coming weather. Unfortunately, on November 14, 1703, any clues they might have seen would not do any good for the people of England. The unusual weather began that day with strong winds from the Atlantic Ocean that battered the southern part of Britain and Wales. The pounding winds damaged many homes and other buildings, but the hurricane-like storm only began doing serious damage on November 26. Then the winds estimated at over 80 miles per hour, blew bricks from some buildings and embedded them in others. Wood beams, separated from buildings, flew through the air and killed hundreds across the south of the country. Towns such as Plymouth, Hull, Cowes, Portsmouth, and Bristol were devastated.

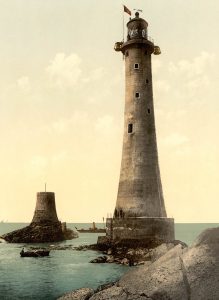

Finally, on November 27, 1703, the storm system finally dissipated over England. For almost two weeks, it had ripped the country nearly to shreds. With its hurricane force winds, the storm killed somewhere between 10,000 and 30,000 people. Hundreds of Royal Navy ships were lost to the storm, the worst in Britain’s history. It was the loss of the 300 Royal Navy ships that really caused the death toll to rise. The ships that were anchored carried some 8,000 sailors. All were lost. Then, the Eddystone Lighthouse, which had been built on a  rock outcropping 14 miles from Plymouth, was blown over by the storm. All of its residents, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were killed. Huge waves on the Thames River sent water six feet higher than ever before recorded near London. More than 5,000 homes along the river were destroyed.

rock outcropping 14 miles from Plymouth, was blown over by the storm. All of its residents, including its designer, Henry Winstanley, were killed. Huge waves on the Thames River sent water six feet higher than ever before recorded near London. More than 5,000 homes along the river were destroyed.

The author Daniel Defoe, witnessed the storm, and it had such an impact on him that he wrote his first book, entitled “The Storm” the following year. In “The Storm” he described the storm as an “Army of Terror in its furious March.” Sometimes the best inspiration for writing a book is the events of real life. Defoe would later go on to write the well known novel “Robinson Crusoe.”