History

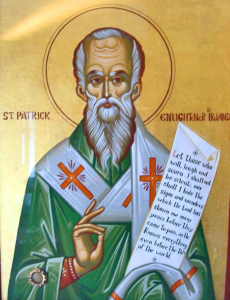

Once a year, we find ourselves puttin’ on a little bit o’ the Irish style, to step out and partake of the green Guinness beer, Corned Beef and Cabbage, and a number of other Irish treats, as we celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day. The day really isn’t about wearing green clothes, so you don’t get pinched, or drinking green beer, but rather a day to celebrate Saint Patrick, who came to Ireland in the fifth century and brought many of the people to Christ. In fact, in Ireland, the day is not a party day, but rather, a religious holiday, similar to Christmas and Easter. Things have changed some over the years, and these days you can find Saint Patrick’s Day parades, shamrocks, and green Guinness beer in Ireland, but it’s mostly there for the tourists who think that is the right way to celebrate the day. For most of the Irish people, however it would not be that way, and in fact, up until 1970 Irish laws mandated that pubs be closed on Saint Patrick’s Day. That is a stark contrast to the way the day is celebrated here, but the holiday doesn’t mean the same thing to Americans. I suppose that our Independence Day doesn’t mean the same thing to the Irish either.

Once a year, we find ourselves puttin’ on a little bit o’ the Irish style, to step out and partake of the green Guinness beer, Corned Beef and Cabbage, and a number of other Irish treats, as we celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day. The day really isn’t about wearing green clothes, so you don’t get pinched, or drinking green beer, but rather a day to celebrate Saint Patrick, who came to Ireland in the fifth century and brought many of the people to Christ. In fact, in Ireland, the day is not a party day, but rather, a religious holiday, similar to Christmas and Easter. Things have changed some over the years, and these days you can find Saint Patrick’s Day parades, shamrocks, and green Guinness beer in Ireland, but it’s mostly there for the tourists who think that is the right way to celebrate the day. For most of the Irish people, however it would not be that way, and in fact, up until 1970 Irish laws mandated that pubs be closed on Saint Patrick’s Day. That is a stark contrast to the way the day is celebrated here, but the holiday doesn’t mean the same thing to Americans. I suppose that our Independence Day doesn’t mean the same thing to the Irish either.

In the United States, Saint Patrick’s Day is a day to celebrate out Irish roots, and to participate in a little playful silliness. We celebrate with “pub crawls” and green coloring in rivers. While the Chicago River is the most prominent green river on Saint Patrick’s Day, there are currently others working to emulate the same effects or have done so in the past. The Irish Marching Society decided to bring the tradition to Rockford, Illinois and dye Rock River last year. San Antonio, Texas; Savannah, Georgia; Indianapolis, Indiana; Charlotte, North Carolina; Tampa, Florida; and Washington DC have all dyed various rivers green. In 2020, city officials in Dublin, Ireland decided to get in on the fun by dying the River Liffey green…as a way to get everyone involved.

I think most of us have some Irish background, but people may not know it. It seems to me that a lot of people have immigrated from Ireland over the years. In fact, many industries like mining and the rail roads, likely

would have been a ways behind where they were with the Irish immigrants. With the number of Irish immigrants that came over, there are probably very few families who don’t have a least a little bit of the Irish in them. Nevertheless, Irish or not, most of us like to celebrate the wearin’ of the green every year when Saint Paddy’s Day rolls around. So, whether you drink green beer or eat corned beef and cabbage, or simply wear green so you don’t get pinched, happy Saint Patrick’s Day to you all!!

would have been a ways behind where they were with the Irish immigrants. With the number of Irish immigrants that came over, there are probably very few families who don’t have a least a little bit of the Irish in them. Nevertheless, Irish or not, most of us like to celebrate the wearin’ of the green every year when Saint Paddy’s Day rolls around. So, whether you drink green beer or eat corned beef and cabbage, or simply wear green so you don’t get pinched, happy Saint Patrick’s Day to you all!!

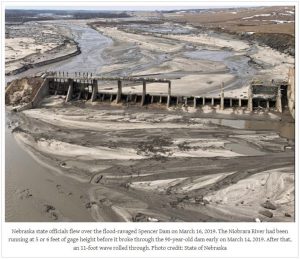

The town of Spencer, Nebraska is a small town of just 423 people, but on March 14, 2019, the town became more well known that it probably ever dreamed it could, or even wanted to be. Suddenly, Spencer, Nebraska was big news, or at least the dam there was. Events unfolded that lead to the collapse of the 93-year-old dam, when the pressure from an icy flood mixed with an area that had a history of unaddressed ice problems. Perhaps it was the rural area of the state, or that they misjudged the surge that could follow a collapse, but they didn’t think that many people would be affected and certainly that no one would die, should the Spencer dam fail. That proved to be untrue, when Kenny Angel, who lived just beneath the dam, was found dead after the flood washed away his home and business. Workers for the Nebraska Public Power District, which operated the dam, warned Angel just minutes ahead of time of the impending danger.

The town of Spencer, Nebraska is a small town of just 423 people, but on March 14, 2019, the town became more well known that it probably ever dreamed it could, or even wanted to be. Suddenly, Spencer, Nebraska was big news, or at least the dam there was. Events unfolded that lead to the collapse of the 93-year-old dam, when the pressure from an icy flood mixed with an area that had a history of unaddressed ice problems. Perhaps it was the rural area of the state, or that they misjudged the surge that could follow a collapse, but they didn’t think that many people would be affected and certainly that no one would die, should the Spencer dam fail. That proved to be untrue, when Kenny Angel, who lived just beneath the dam, was found dead after the flood washed away his home and business. Workers for the Nebraska Public Power District, which operated the dam, warned Angel just minutes ahead of time of the impending danger.

The dam was operated by the Nebraska Public Power District (NPPD). Heavy precipitation during the March 2019 North American blizzard led to a failure of the dam in the early morning hours of March 14th, causing heavy flooding downstream. For a dam that was not expected to do much damage, if it failed, the damage was really devastating…affecting four counties. An 11-foot wall of water was released by the failure, as recorded by a US Geological Survey stream gage moments before it was washed away.

Nebraska regulators had categorized Spencer Dam as a “significant hazard,” which is a rating that meant no loss of life was expected if it failed. With that, no formal emergency action plan was required. After the collapse, it was noted that the Association of State Dam Safety Officials said the dam should have been rated as “high hazard,” which could have led to a plan to modify it to increase its flood capacity. Unfortunately, that was not done, and the failure was terrible. Knox County, the hardest hit of the four counties affected, saw estimates of more than $17M in damages. While the Spencer dam had a history of ice related issues, and other dams may have had ice issues too, the Spencer dam might just be the first dam in the nation to collapse due to

those ice issues. The 11-foot surge of water that followed the collapse took out roads, highways, homes, businesses, and bridges. For several months, motorists were required to detour 150 miles to get past the damage. The flood cut a new channel in the river, meaning a new 1050-foot section of the bridge on Highway 281 below the dam.

those ice issues. The 11-foot surge of water that followed the collapse took out roads, highways, homes, businesses, and bridges. For several months, motorists were required to detour 150 miles to get past the damage. The flood cut a new channel in the river, meaning a new 1050-foot section of the bridge on Highway 281 below the dam.

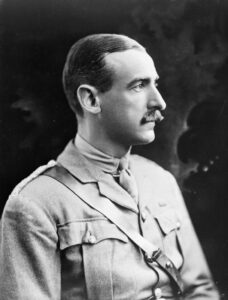

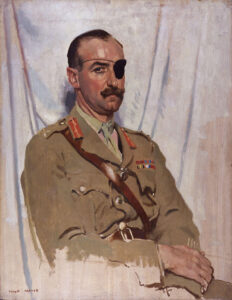

The unkillable soldier…a nickname that has deep ramifications, and a nickname no one really wants to have. It indicates that the soldier is wounded multiple times…and somehow survived. General Adrian Carton de Wiart was that soldier. He was born into an aristocratic family in Brussels, on May 5, 1880. He was the eldest son of Léon Constant Ghislain Carton de Wiart and Ernestine Wenzig. He spent his early days in Belgium and in England. When he was six years old, his parents divorced, and he moved with his father to Cairo. His mother remarried Demosthenes Gregory Cuppa later in 1886. His father was a lawyer and magistrate, as well as a director of the Cairo Electric Railways and Heliopolis Oases Company and was well connected in Egyptian governmental circles. Adrian Carton de Wiart learned to speak Arabic. He joined the British Army at the time of the Second Boer War around 1899, where he entered under the false name of “Trooper Carton,” claiming to be 25 years old, but he was actually 20. He was wounded in the stomach and groin in South Africa early in the Second Boer War and was sent home to recuperate. His father was furious when he learned his son had abandoned his studies. Nevertheless, he allowed his son to remain in the army.

The unkillable soldier…a nickname that has deep ramifications, and a nickname no one really wants to have. It indicates that the soldier is wounded multiple times…and somehow survived. General Adrian Carton de Wiart was that soldier. He was born into an aristocratic family in Brussels, on May 5, 1880. He was the eldest son of Léon Constant Ghislain Carton de Wiart and Ernestine Wenzig. He spent his early days in Belgium and in England. When he was six years old, his parents divorced, and he moved with his father to Cairo. His mother remarried Demosthenes Gregory Cuppa later in 1886. His father was a lawyer and magistrate, as well as a director of the Cairo Electric Railways and Heliopolis Oases Company and was well connected in Egyptian governmental circles. Adrian Carton de Wiart learned to speak Arabic. He joined the British Army at the time of the Second Boer War around 1899, where he entered under the false name of “Trooper Carton,” claiming to be 25 years old, but he was actually 20. He was wounded in the stomach and groin in South Africa early in the Second Boer War and was sent home to recuperate. His father was furious when he learned his son had abandoned his studies. Nevertheless, he allowed his son to remain in the army.

In 1908, he married Countess Friederike Maria Karoline Henriette Rosa Sabina Franziska Fugger von Babenhausen (1887 – 1949), eldest daughter of Karl, 5th Fürst (Prince) von Fugger- Babenhausen and Princess Eleonora zu Hohenlohe-Bartenstein und Jagstberg of Klagenfurt, Austria. They had two daughters, the elder of whom Anita (born 1909, now deceased) was the maternal grandmother of the war correspondent Anthony Loyd (born 1966). I wonder if Loyd was inspired by his grandfather’s story.

Babenhausen and Princess Eleonora zu Hohenlohe-Bartenstein und Jagstberg of Klagenfurt, Austria. They had two daughters, the elder of whom Anita (born 1909, now deceased) was the maternal grandmother of the war correspondent Anthony Loyd (born 1966). I wonder if Loyd was inspired by his grandfather’s story.

Over the course of his career, General Adrian Carton de Wiart earned the nickname “the unkillable soldier.” By 1915, he was promoted to captain and had already survived his first war…the Boer War. One night, near the French battlefield of Ypres, he and a small group of officers wandered too far into enemy territory and ran into a group of German soldiers, who fired. De Wiart was badly shot in the hand but scrambled back to his regiment. According to his memoirs, he used a “scarf he’d taken off a slain German soldier to stop the bleeding.” He was taken to a hospital where surgeons debated what to do about the gory mess of dangling fingers that had been his hand. De Wiart said, “I asked the doctor to take my fingers off; he refused, so I pulled them off myself and felt absolutely no pain in doing it.” De Wairt’s injuries were not over yet. The hand became infected and later had to be amputated. Three weeks later, De Wiart and returned to duty. He was shot several more times in his career, survived two plane crashes, and lost an eye. Over the course of four conflicts,  he sustained 11 grievous injuries, and simply could not be killed in war.

he sustained 11 grievous injuries, and simply could not be killed in war.

En route home via French Indochina, Carton de Wiart stopped in Rangoon as a guest of the army commander. Coming down the stairs, he slipped on coconut matting, fell down, broke several vertebrae, and knocked himself unconscious. He was admitted to Rangoon Hospital where he was treated and recovered. His wife died in 1949. Then, in 1951, at the age of 71, he married Ruth Myrtle Muriel Joan McKechnie, a divorcee known as Joan Sutherland, 23 years his junior (born in late 1903, she died January 13, 2006, at the age of 102.) They settled at Aghinagh House, Killinardrish, County Cork, Ireland. Carton de Wiart died at the age of 83 on June 5, 1963. He left no papers. He and his wife Joan are buried in Caum Churchyard just off the main Macroom road. The grave site is just outside the actual graveyard wall on the grounds of his own home.

As most of us know, dogs have been used in many kinds of work from K-9 units to military units to guide dogs, to cadaver dogs, and many more. During World War II, one such dog named Chips, who was a Shepherd-Collie-Husky mix, served for 3.5 years of the war. When the US entered World War II, the military actually asked Americans to “donate” their dogs to serve on patrols and guard duty. That seems so strange to me. How could the dog know what was going on? How could it not get depressed or aggressive, thinking its owner was dead or had abandoned it? It’s one thing to send a soldier into a war situation, they have either been legally drafted or they freely joined up, but a dog…or any animal for that matter, couldn’t possibly understand why, after having a family of their own, they were suddenly in a foreign country, without their owner, their own bed, or their home.

As most of us know, dogs have been used in many kinds of work from K-9 units to military units to guide dogs, to cadaver dogs, and many more. During World War II, one such dog named Chips, who was a Shepherd-Collie-Husky mix, served for 3.5 years of the war. When the US entered World War II, the military actually asked Americans to “donate” their dogs to serve on patrols and guard duty. That seems so strange to me. How could the dog know what was going on? How could it not get depressed or aggressive, thinking its owner was dead or had abandoned it? It’s one thing to send a soldier into a war situation, they have either been legally drafted or they freely joined up, but a dog…or any animal for that matter, couldn’t possibly understand why, after having a family of their own, they were suddenly in a foreign country, without their owner, their own bed, or their home.

Nevertheless, when their country asked, over 11,000 Americans volunteered their pets, including Chips’s owner, John Wren of Pleasantville, New York. Chips the first “volunteer” dog in the United States, took part in the invasion of Sicily, just a year into his deployment. When an Italian machine gunner pinned down Chips and his squad, he broke away from his leash and charged into the enemy position. A single shot rang out. Then, the Italian gunner emerged with Chips at his throat, followed by three more soldiers. They all quickly surrendered. Chips received a wound on his scalp and burns on his mouth and left eye. That didn’t stop this hero dog, who kept fighting and helped capture 10 more soldiers that day.

After the war, per their request, it was time for Chips to be returned to his family. Plans would have to be put in place for that to happen. So, in the fall of 1945 he was taken back to Front Royal where he was retrained so that he could go back to his family. A dog who had been in combat couldn’t just go back to his family as if nothing had happened. Finally in December of 1945, he traveled home to Pleasantville, riding in the baggage car of a train. He didn’t go alone. He was accompanied by six reporters and photographers who wanted to

cover the story. They were met by Mr and Mrs Wren and their son, Johnny, who was only a baby when Chips left. The girls raced home after school to see their dog. It was a sweet homecoming. Chips lived for just four months before his kidneys failed. I guess war had taken its toll.

cover the story. They were met by Mr and Mrs Wren and their son, Johnny, who was only a baby when Chips left. The girls raced home after school to see their dog. It was a sweet homecoming. Chips lived for just four months before his kidneys failed. I guess war had taken its toll.

Chips’s story made him an international sensation. He received a Silver Star for his heroics. Unfortunately, some people thought that a dog shouldn’t be awarded the same medal as a human, so it was revoked. Then, in 2018, he was awarded the PDSA Dickin Award, the highest honor for wartime bravery for an animal. A well-deserved honor. While his award was amazing, I think that the family should have also received an award, as should all of the other families who donated their dogs for the war effort. It was a very selfless act.

The day after the debut of the Barbi doll on March 9, 1959, at the American Toy Fair in New York City, the doll had become an instant sensation. Basically, her debut makes Barbie 63 years old. The old girl has aged very well. In fact, she hasn’t aged a bit, although she can’t say she hasn’t had any work done. The reality is that Barbie has been redesigned at least every year. Of course, that isn’t saying she has had plastic surgery…or is it? She is, after all, made of plastic.

The day after the debut of the Barbi doll on March 9, 1959, at the American Toy Fair in New York City, the doll had become an instant sensation. Basically, her debut makes Barbie 63 years old. The old girl has aged very well. In fact, she hasn’t aged a bit, although she can’t say she hasn’t had any work done. The reality is that Barbie has been redesigned at least every year. Of course, that isn’t saying she has had plastic surgery…or is it? She is, after all, made of plastic.

Barbie stands eleven inches tall, and at first anyway, had long blond hair. These days, of course as hairstyles have changed and it was decided that not all girls are blonds, her hair color and style have changed with the times. She has been given lots of cool clothes, shoes, a house, car, RV, and boat…and probably many other things. Barbie was the first mass-produced toy doll in the United States with adult features. I suppose that she caused quite a stir with many parents, but for girls everywhere, she was the princess they were going to be when they grew up. I know I couldn’t wait to get one.

The woman behind Barbie was Ruth Handler, who co-founded Mattel, Inc with her husband in 1945. Handler witnessed her young daughter ignore her baby dolls to play make-believe with paper dolls of adult women, at which point she realized there was an important niche in the market for a toy that allowed little girls to imagine the future. Barbie’s appearance was modeled on a doll named Lilli, based on a German comic strip character. Lilli was originally marketed as a racy gag gift to adult men in tobacco shops, but she later became extremely popular with children. Mattel bought the rights to Lilli and made its own version, which Handler named after her daughter, Barbara.

In 1955, Mattel became a sponsor of the “Mickey Mouse Club” TV program. With that, Mattel became one of the first toy companies to broadcast commercials aimed specifically at children. They used their commercials to promote their new toy, and by 1961, the enormous consumer demand for the doll led Mattel to release a boyfriend for Barbie. Handler named him Ken, after her son. Then, Barbie’s best friend, Midge, came out in 1963; her little sister, Skipper, debuted in 1964.

Of course, the Barbie doll was not without controversy. On a positive note, many women saw Barbie as providing an alternative to traditional 1950s gender roles. Her many careers, like airline stewardess, doctor, pilot, astronaut, Olympic athlete, and even US presidential candidate made some women see a possible future that was different

than was common in the 1950s. Others thought Barbie’s never-ending supply of designer outfits, cars, and “Dream Houses” encouraged kids to be materialistic. However, the biggest controversy was over Barbie’s appearance. Her figure was unrealistic for a real woman. It was estimated that if she were a real woman, her measurements would be 36-18-38–led many to claim that Barbie provided little girls with an unrealistic and harmful example and fostered negative body image. Nevertheless, even with the criticism, Barbie never lost her appeal, and in fact she is as popular today as she ever was. I was just 3 years old when Barbie came out, and today, my great granddaughter, Cambree Petersen loves her Barbie dolls as much as I did, even if Barbie is…old!!!

than was common in the 1950s. Others thought Barbie’s never-ending supply of designer outfits, cars, and “Dream Houses” encouraged kids to be materialistic. However, the biggest controversy was over Barbie’s appearance. Her figure was unrealistic for a real woman. It was estimated that if she were a real woman, her measurements would be 36-18-38–led many to claim that Barbie provided little girls with an unrealistic and harmful example and fostered negative body image. Nevertheless, even with the criticism, Barbie never lost her appeal, and in fact she is as popular today as she ever was. I was just 3 years old when Barbie came out, and today, my great granddaughter, Cambree Petersen loves her Barbie dolls as much as I did, even if Barbie is…old!!!

How can the February Revolution begin on March 8th, you might ask? Well, if you know much about 1917 Russia, you know that the calendar at that time was the Julian calendar, and not the Gregorian calendar that we use today in most countries. That was how the February Revolution (known as such because of Russia’s use of the Julian calendar) which began on February 23rd in the Julian calendar, actually began on March 8th in the now-used Gregorian calendar. The February Revolution started with riots and strikes over the scarcity of food erupt in Petrograd. One week later, centuries of czarist rule in Russia ended with the abdication of Czar Nicholas II, and Russia took a dramatic step closer to a communist revolution.

How can the February Revolution begin on March 8th, you might ask? Well, if you know much about 1917 Russia, you know that the calendar at that time was the Julian calendar, and not the Gregorian calendar that we use today in most countries. That was how the February Revolution (known as such because of Russia’s use of the Julian calendar) which began on February 23rd in the Julian calendar, actually began on March 8th in the now-used Gregorian calendar. The February Revolution started with riots and strikes over the scarcity of food erupt in Petrograd. One week later, centuries of czarist rule in Russia ended with the abdication of Czar Nicholas II, and Russia took a dramatic step closer to a communist revolution.

By 1917, Czar Nicholas II had already lost all of his credibility. The corruption in the government was rampant, the economy was a mess, and Nicholas repeatedly dissolved the Duma…the Russian parliament established after the Revolution of 1905…whenever it opposed his will. All that was bad, but the immediate cause of the February Revolution, which was the first phase of the Russian Revolution of 1917…was Russia’s disastrous involvement in World War I. Militarily, Russia was no match for industrialized Germany, and Russian casualties were greater than those sustained by any nation in any previous war. They were severely pounded by the Germans. Meanwhile, the economy was hopelessly disrupted by the costly war effort, and moderates joined Russian radical elements in calling for the overthrow of the czar, who was already weak due to family problems, namely a sick child.

While most of the world switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1582, Russia didn’t make the conversion until 1918. So, 104 years ago, the Russian people irrevocably had half a month wiped out of their lives…13 days of February in 1918. Their calendar went from January 31, 1918, to February 14, 1918…overnight. On March 8th or February 23rd, 1917, depending on the calendar you choose to use for the event, demonstrators were clamoring for bread in the streets of the Russian capital of Petrograd (now known as Saint Petersburg). Supported by 90,000 men and women on strike, the protesters clashed with police but refused to leave the streets. The strike spread, and on March 10th, it had spread among all of Petrograd’s workers, and irate mobs of workers destroyed police stations. Several factories elected deputies to the Petrograd Soviet, or “council” of workers’ committees, following the model devised during the Revolution of 1905.

By March 11th, the troops of the Petrograd army garrison ordered soldiers to crush the uprising. Regiments opened fire, killing demonstrators, but the protesters kept to the streets, and the troops began to waver. Nicholas dissolved the Duma again on that day, and on March 12, the revolution triumphed when regiment after regiment of the Petrograd garrison defected to the cause of the demonstrators. The soldiers, some 150,000 men, subsequently formed committees that elected deputies to the Petrograd Soviet.

The uprising forced the imperial government to resign, and the Duma formed a provisional government that peacefully vied with the Petrograd Soviet for control of the revolution. March 14th, saw the Petrograd Soviet  issuing “Order No. 1,” which instructed Russian soldiers and sailors to obey only those orders that did not conflict with the directives of the Soviet. Czar Nicholas II abdicated the throne the next day, March 15th, in favor of his brother Michael, who refused the crown, ending the czarist autocracy.

issuing “Order No. 1,” which instructed Russian soldiers and sailors to obey only those orders that did not conflict with the directives of the Soviet. Czar Nicholas II abdicated the throne the next day, March 15th, in favor of his brother Michael, who refused the crown, ending the czarist autocracy.

The Petrograd Soviet tolerated the new provincial government and hoped to salvage the Russian war effort while ending the food shortage and many other domestic crises…a daunting task. Meanwhile, Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik revolutionary party, left his exile in Switzerland and crossed German enemy lines to return home and take control of the Russian Revolution.

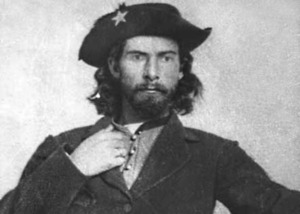

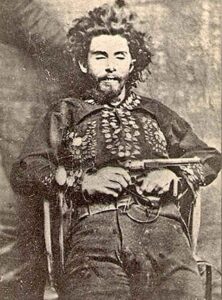

William T Anderson’s life was always rather a violent one, but it escalated when his sister died while in the custody of the Union soldiers during the Civil War. Anderson was born around 1840 in Hopkins County, Kentucky, to William and Martha Anderson. His siblings were Jim, Ellis, Mary, Josephine, and Martha. His schoolmates recalled him as a well-behaved, reserved child, so they might be surprised to see how he ended up. Anderson began to support himself early on, by stealing and selling horses in 1862. After a Union loyalist judge killed his father, Anderson killed the judge and fled to Missouri. He was always one to exact revenge for anything in which he felt that he or his family were wronged. In Missouri, he robbed travelers and killed several Union soldiers.

William T Anderson’s life was always rather a violent one, but it escalated when his sister died while in the custody of the Union soldiers during the Civil War. Anderson was born around 1840 in Hopkins County, Kentucky, to William and Martha Anderson. His siblings were Jim, Ellis, Mary, Josephine, and Martha. His schoolmates recalled him as a well-behaved, reserved child, so they might be surprised to see how he ended up. Anderson began to support himself early on, by stealing and selling horses in 1862. After a Union loyalist judge killed his father, Anderson killed the judge and fled to Missouri. He was always one to exact revenge for anything in which he felt that he or his family were wronged. In Missouri, he robbed travelers and killed several Union soldiers.

Anderson became a guerrilla, when his family was living in Council Grove, Territory of Kansas at the start of the Civil War. After William Quantrill’s raid on Aubry, Kansas on March 7, 1862, a Federal company from Olathe, Kansas sent a patrol from Company D, Eighth Kansas Jayhawker Regiment to investigate. Their mission was to seek out Southern sympathizers living nearby, who might be accused of aiding the raiders. Anderson’s father and uncle were named as such, and when the Jayhawker company arrived at the Anderson farm on March 11th, William and his younger brother Jim were delivering 15 head of cattle to the US commissary agent at Fort Leavenworth. When the brothers returned to their farm, they found their father and uncle hanged in retaliation, their home burned to the ground, and all their possessions stolen. It was an act of war in their minds, because the men had no chance to defend themselves. Two days later Bill and his brother Jim were both riding with Quantrill’s Raiders, a group of Confederate guerrillas operating along the Kansas–Missouri border. Anderson moved his sisters from Kansas, and for a year they lived at various places stopping finally with the Mundy family on the Missouri side of the line near Little Santa Fe. When asked why he joined Quantrill, Anderson replied by saying, “I have chosen guerrilla warfare to revenge myself for wrongs that I could not honorable revenge otherwise. I lived in Kansas when this war commenced. Because I would not fight the people of Missouri, my native State, the Yankees sought my life but failed to get me. [They] revenged themselves by murdering my father, [and] destroying all my property.”

Anderson became a skilled bushwhacker and quickly earned the trust of the group’s leaders, William Quantrill and George M Todd. It was his bushwhacking skills that ultimately marked him as a dangerous man…and eventually led the Union to imprison his sisters. Then, after a building collapse in the makeshift jail in Kansas City, Missouri, left one of his sisters dead, while in custody and the others permanently maimed, Anderson devoted himself to revenge. He took a leading role in the Lawrence Massacre and later took part in the Battle of Baxter Springs, both in 1863. He later satisfied his revenge by hijacking a train full of Union troops and slaughtering 24 of them, thus giving him the name “Bloody Bill” Anderson.

By 1863, all Bill had left was a brother and two sisters, who had miraculously survived the August 13 Union jail collapse in Kansas City. The collapse wasn’t an accident. Union guards from the 9th Kansas Jayhawker Regiment, serving as provost guards in town, intentionally collapsed a three-story brick building on a number of young Southern female prisoners. Fourteen-year-old Josephine Anderson was killed in the collapse. Bill’s ten-year-old sister Martha’s legs were horribly crushed crippling her for life, and his sixteen-year-old sister Mary suffered serious back injuries and facial lacerations. Both girls would carry their physical and emotional scars for the rest of their lives. War is an ugly thing, and unfortunately, sometimes unscrupulous people do things  they shouldn’t. The atrocity at the jail was a war crime and should have been punished as such, but I suppose that didn’t justify the murders that followed, because there was no proof that those murdered were involved in any way.

they shouldn’t. The atrocity at the jail was a war crime and should have been punished as such, but I suppose that didn’t justify the murders that followed, because there was no proof that those murdered were involved in any way.

Union military leaders ordered Lieutenant Colonel Samuel P Cox to kill Anderson and provided him with a group of experienced soldiers. A local woman saw Anderson soon after he left Glasgow and told Cox where he was. On October 26, 1864, Cox pursued Anderson’s group with 150 men and engaged them in a battle called the Skirmish at Albany, Missouri. Anderson and his men charged the Union forces, killing five or six of them, but turned back under heavy fire. Only Anderson and one other man, the son of a Confederate general, continued to charge after the others had retreated. Anderson was hit by a bullet behind an ear, which most likely killed him instantly. Four other guerrillas were killed in the attack as well. The victory made a hero of Cox and led to his promotion.

Sometimes, I am amazed at what you can “sell” people. In 1977, one of Elvis Presley’s assistants saw an opportunity when Elvis didn’t finish a glass of water after a concert. The assistant held an auction and sold the few drops of water left in the glass for $455. And then, there was the two golf balls that were sold for $1400. So, what made these golf balls so special…well, they were swallowed by a python. The snake had to have surgery to remove them, and they were sold after. A British artist, after going through a period of depression, during which she simply stayed in bed, decided to sell the ensuing messy bedroom “furnishings,” so she auctioned them off for $150,000 after calling them “My Bed.” And let us not forget that on March 6, 2012, a woman from Nebraska sold a three-year-old McDonald’s Chicken McNugget for $8100 because it resembled George Washington. She was raising the money to send children to summer camp. The auction site apparently eased its rules on selling expired food for the woman, so that she could raise money to support her cause.

Sometimes, I am amazed at what you can “sell” people. In 1977, one of Elvis Presley’s assistants saw an opportunity when Elvis didn’t finish a glass of water after a concert. The assistant held an auction and sold the few drops of water left in the glass for $455. And then, there was the two golf balls that were sold for $1400. So, what made these golf balls so special…well, they were swallowed by a python. The snake had to have surgery to remove them, and they were sold after. A British artist, after going through a period of depression, during which she simply stayed in bed, decided to sell the ensuing messy bedroom “furnishings,” so she auctioned them off for $150,000 after calling them “My Bed.” And let us not forget that on March 6, 2012, a woman from Nebraska sold a three-year-old McDonald’s Chicken McNugget for $8100 because it resembled George Washington. She was raising the money to send children to summer camp. The auction site apparently eased its rules on selling expired food for the woman, so that she could raise money to support her cause.

Granted these items are novelties, and some went for a good cause, but seriously…people will pay good money  for the strangest things. It actually makes me want to look through my own possessions to see what oddities I might have that would bring in millions of dollars, because apparently, they could sell. You just never know. What is it that makes people decide that they need a few drops of water left in a glass after Elvis drank from the glass, or a McNugget that looks like George Washington, or the many food items that have looked like the Virgin Mary? I suppose that if these things are for a good cause, maybe they are simply donating for the purpose of helping the cause. Or maybe they actually see value in the item or items they are bidding on.

for the strangest things. It actually makes me want to look through my own possessions to see what oddities I might have that would bring in millions of dollars, because apparently, they could sell. You just never know. What is it that makes people decide that they need a few drops of water left in a glass after Elvis drank from the glass, or a McNugget that looks like George Washington, or the many food items that have looked like the Virgin Mary? I suppose that if these things are for a good cause, maybe they are simply donating for the purpose of helping the cause. Or maybe they actually see value in the item or items they are bidding on.

I suppose that in the case of “seeing value” in an item that almost no one else sees value in, I would have to  say…to each his own, but that for the amount some of these items went, there must have been a few people who could see value in something seemingly worthless…at least to me. That said, I decided to go out to an auction site to see what “treasures” I could find. I was somewhat disappointed in that I found no expired food items, or famously worthless celebrity use items. Mostly what I saw were items that did have some value, depending on your need…things like bags full of vintage doll clothes, old pitchers and glassware, belt buckles, automobile emblems, vintage cigarette lighters, coins, and vintage toys. Some of these things could very easily have great value, in that the vintage items could be rare collectables. Nevertheless, I didn’t see anything I couldn’t live without, nor did I find anything that was going for a very high price. I suppose that it would be a rare thing to come across something that cost you nothing, but sold for millions. Still, the idea of selling something for big money isn’t a bad one. It’s just a matter of finding the right item, presenting it to the right audience, and finding yourself feeling very shocked when it sold for the big bucks.

say…to each his own, but that for the amount some of these items went, there must have been a few people who could see value in something seemingly worthless…at least to me. That said, I decided to go out to an auction site to see what “treasures” I could find. I was somewhat disappointed in that I found no expired food items, or famously worthless celebrity use items. Mostly what I saw were items that did have some value, depending on your need…things like bags full of vintage doll clothes, old pitchers and glassware, belt buckles, automobile emblems, vintage cigarette lighters, coins, and vintage toys. Some of these things could very easily have great value, in that the vintage items could be rare collectables. Nevertheless, I didn’t see anything I couldn’t live without, nor did I find anything that was going for a very high price. I suppose that it would be a rare thing to come across something that cost you nothing, but sold for millions. Still, the idea of selling something for big money isn’t a bad one. It’s just a matter of finding the right item, presenting it to the right audience, and finding yourself feeling very shocked when it sold for the big bucks.

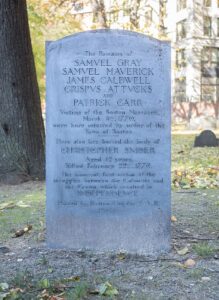

A mob of American colonists gathered at the Customs House in Boston, on the cold, snowy night of March 5, 1770. They called themselves Patriots, and they were there to protest the occupation of their city by British troops, who were sent to Boston in 1768 to enforce unpopular taxation measures passed by a British parliament that lacked American representation. I suppose it is possible that the colonists would have agreed to increase their taxes in an effort to help pay for the Seven-Year War, but the reality is that they were not asked…they were told, and it was to be forced upon them. They were not going tolerate that…so they would fight.

A mob of American colonists gathered at the Customs House in Boston, on the cold, snowy night of March 5, 1770. They called themselves Patriots, and they were there to protest the occupation of their city by British troops, who were sent to Boston in 1768 to enforce unpopular taxation measures passed by a British parliament that lacked American representation. I suppose it is possible that the colonists would have agreed to increase their taxes in an effort to help pay for the Seven-Year War, but the reality is that they were not asked…they were told, and it was to be forced upon them. They were not going tolerate that…so they would fight.

For their part, the British would also not be moved, and they were prepared to fight. British Captain Thomas Preston, the commanding officer at the Customs House, ordered his men to fix their bayonets and join the guard outside the building. The colonists…somewhat less prepared, responded by throwing snowballs and other objects at the British regulars. As the snowball fight commenced, Private Hugh Montgomery was hit, and not knowing what hit him, he discharged his rifle at the crowd. With that, the other soldiers began firing too, and when the smoke cleared, five colonists were dead or dying. They were Crispus Attucks, Patrick Carr, Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick and James Caldwell. Three more were injured. Although it is unclear whether Crispus Attucks, an African American, was the first to fall as is commonly believed, the deaths of the five men are regarded by some historians as the first fatalities in the American Revolutionary War. After the massacre, the British soldiers were put on trial for war crimes. Strangely, patriots John Adams and Josiah Quincy agreed  to defend the soldiers in a show of support of the colonial justice system. When the trial ended in December 1770, two of the British soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter. As punishment, their thumbs were branded with an “M” for murder. In my mind, that is such a minor punishment, for what we view as such a major crime. I’m not sure if I think that any of the British soldiers were really guilty of murder, or even manslaughter, because it seems to me that in a moment of panic, the soldier mistakenly thought he was in eminent danger, when in reality, it was simply a snowball. Still, the punishment really didn’t fit the crime for which it was given.

to defend the soldiers in a show of support of the colonial justice system. When the trial ended in December 1770, two of the British soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter. As punishment, their thumbs were branded with an “M” for murder. In my mind, that is such a minor punishment, for what we view as such a major crime. I’m not sure if I think that any of the British soldiers were really guilty of murder, or even manslaughter, because it seems to me that in a moment of panic, the soldier mistakenly thought he was in eminent danger, when in reality, it was simply a snowball. Still, the punishment really didn’t fit the crime for which it was given.

The Stamp Act was called the “Boston Massacre” by the Sons of Liberty, a Patriot group formed in 1765 to oppose it. The “Boston Massacre” was viewed as a battle for American liberty and just cause for the removal of British troops from Boston. Patriot Paul Revere made an engraving of the incident, depicting the British soldiers lining up like an organized army to suppress an idealized representation of the colonist uprising. Copies of the engraving were distributed throughout the colonies. This was to help reinforce negative American sentiments about British rule. The colonists needed as many in their ranks to be onboard with the battle, and so any depiction of the British as cruel slave masters would help.

The American Revolution officially began in April of 1775, when British troops from Boston fought with American militiamen at the battles of Lexington and Concord. The British troops were under orders to capture  Patriot leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock in Lexington and to confiscate the Patriot arsenal at Concord. Unfortunately for them, the Patriots were several steps ahead of them, and neither of the missions were accomplished because Paul Revere and William Dawes rode ahead of the British to warn Adams and Hancock and to rouse the Patriot minutemen.

Patriot leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock in Lexington and to confiscate the Patriot arsenal at Concord. Unfortunately for them, the Patriots were several steps ahead of them, and neither of the missions were accomplished because Paul Revere and William Dawes rode ahead of the British to warn Adams and Hancock and to rouse the Patriot minutemen.

The British forces were forced to evacuate Boston eleven months later, in March 1776, following American General George Washington’s successful placement of fortifications and cannons on Dorchester Heights. Oddly the eight-year British occupation of Boston ended with a bloodless liberation of the city. General Washington, commander of the Continental Army, was presented with the first medal ever awarded by the Continental Congress for the victory. It would be more than five years before the Revolutionary War came to an end with British General Charles Cornwallis’ surrender to Washington at Yorktown, Virginia.

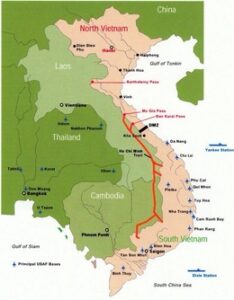

Many people believe that there was no good reason for the war in Vietnam. It seemed like a war we were not going to be allowed to win, and many thought it should have been one we just stayed out of. Vietnam became a French colony in 1877 with the founding of French Indochina, which included Tonkin, Annam, Cochin China and Cambodia…Laos was added in 1893. The French lost control of their colony briefly during World War II, when Japanese troops occupied Vietnam.

Many people believe that there was no good reason for the war in Vietnam. It seemed like a war we were not going to be allowed to win, and many thought it should have been one we just stayed out of. Vietnam became a French colony in 1877 with the founding of French Indochina, which included Tonkin, Annam, Cochin China and Cambodia…Laos was added in 1893. The French lost control of their colony briefly during World War II, when Japanese troops occupied Vietnam.

After the war, Japan and France continued to fight over Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh, a revolutionary leader inspired by Lenin’s Bolshevik Revolution began forming an independence movement. He established the League for the Independence of Vietnam, better known as the Viet Minh, in May of 1941. On September 2, 1945, he declared Vietnam’s independence from France, just hours after Japan’s surrender in World War II. When the French rejected his plan, the Viet Minh resorted to guerilla warfare to fight for an independent Vietnam.

One of the most well-known campaigns of the Vietnam War was codenamed Operation Rolling Thunder. It was an American bombing campaign in which US military aircraft attacked targets throughout North Vietnam from March 1965 to October 1968. This operation was intended to put military pressure on North Vietnam’s communist leaders, thereby reducing their capacity to wage war against the US-supported government of South Vietnam. With that, operation American began its involvement began, not only its assault on North Vietnamese territory, but the expansion of US involvement in the Vietnam War.

By the 1950s, the US military began providing equipment and advisors to help the government of South Vietnam to resist a communist takeover by North Vietnam and its South Vietnam-based allies, the Viet Cong guerrilla fighters. The American military initiated limited air operations within South Vietnam in 1962, in an effort to offer air support to South Vietnamese army forces, destroy suspected Viet Cong bases, and spray herbicides such as Agent Orange to eliminate jungle cover. It was an ugly time for anyone in the area. In August 1964, President Lyndon B Johnson expanded American air operations, when he authorized retaliatory air strikes against North Vietnam following a reported attack on US warships in the Gulf of Tonkin. Later that year, Johnson approved  limited bombing raids on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of pathways that connected North Vietnam and South Vietnam by way of neighboring Laos and Cambodia. The president’s goal was to disrupt the flow of manpower and supplies from North Vietnam to its Viet Cong allies. Nothing the United States tried really worked to remove the tensions in the area, and so in 1963, the United States withdrew from Vietnam. Unfortunately, they left behind bombs and land mines from Operation Rolling Thunder and other bombing campaigns of the Vietnam War. By some estimates, those bombs and land mines have killed or injured tens of thousands of Vietnamese people since the United States withdrew its combat troops in 1973.

limited bombing raids on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a network of pathways that connected North Vietnam and South Vietnam by way of neighboring Laos and Cambodia. The president’s goal was to disrupt the flow of manpower and supplies from North Vietnam to its Viet Cong allies. Nothing the United States tried really worked to remove the tensions in the area, and so in 1963, the United States withdrew from Vietnam. Unfortunately, they left behind bombs and land mines from Operation Rolling Thunder and other bombing campaigns of the Vietnam War. By some estimates, those bombs and land mines have killed or injured tens of thousands of Vietnamese people since the United States withdrew its combat troops in 1973.