History

During the gold rush years, in 1857, to be exact, two German men who had been traveling with a wagon train headed to California, decided to leave the rest of the group and headed out on their own. They wound up in the Mono Lake region of northern California. One of the men would later describe the area as “the burnt country.” While crossing the Sierra Nevada near the headwaters of the Owens River, they sat down to rest near a stream. Looking around, they noticed a curious looking rock ledge of red lava filled with what appeared to be pure lumps of gold “cemented” together. That was how their “mine” got its name.

During the gold rush years, in 1857, to be exact, two German men who had been traveling with a wagon train headed to California, decided to leave the rest of the group and headed out on their own. They wound up in the Mono Lake region of northern California. One of the men would later describe the area as “the burnt country.” While crossing the Sierra Nevada near the headwaters of the Owens River, they sat down to rest near a stream. Looking around, they noticed a curious looking rock ledge of red lava filled with what appeared to be pure lumps of gold “cemented” together. That was how their “mine” got its name.

The ledge of that hillside was literally loaded with the ore. The excited men couldn’t believe their eyes. One of the men was laughing at the other as he pounded away about ten pounds of the ore to take with him…because he did not believe it was really gold. The man who believe that it was gold drew a map to the location and the two men continued their journey. Along the way, the disbeliever died and since he was laden with so much ore, the believer tossed the majority of the samples. Then, after crossing the mountains, he followed the San Joaquin River to the mining camp of Millerton, California. After a long, weary journey, the German had become ill and soon went to San Francisco for treatment. He was diagnosed and cared for by a Doctor Randall who told the man he was terminally ill with consumption (tuberculosis). With no money to pay the doctor and too ill to return to the treasure, he paid his caretaker with the ore, the map he had drawn, and provided him with a detailed description.

Doctor Randall shared this knowledge with a few of his friends and together they decided to go for the gold. They arrived at old Monoville in the spring of 1861. After enlisting additional men to help, Randall’s group began to prospect on a quarter-section of land called Pumice Flat. Their claim is thought to have been some eight miles north of Mammoth Canyon…the 120 acres were near what became known as Whiteman’s Camp. Word of possibly a huge cache of gold spread quickly and before long miners flooded the area hunting for the gold laden red “cement.” One story tells that two of Doctor Randall’s party had in fact found the “Cement Mine,” taking several thousand dollars from the ledge. Unfortunately, for those two men, the area was filled with the Owens Valley Indian War which began in 1861. The Paiute Indians, who had heretofore been generally peaceful, were angered at the large numbers of prospectors who had invaded their lands. The two miners who  had allegedly found the lost ledge were killed by the Indians before they were able to tell of its location.

had allegedly found the lost ledge were killed by the Indians before they were able to tell of its location.

Though the “cement” outcropping was never found again, the many prospectors who flooded the eastern Sierra region did find gold. Apparently there was a huge cache there after all. This resulted in the mining camps of Dogtown, Mammoth City, Lundy Canyon, Bodie, and many others. The lost lode is said to lie somewhere in the dense woods near the Sierra Mountain headwaters of the San Joaquin River’s middle fork. If it really exists, it must be very well hidden.

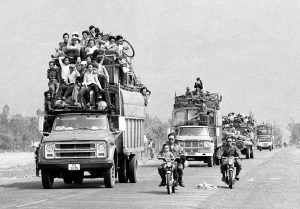

From November 1, 1955 until April 30, 1975, the Vietnam war raged. The United States entered the war on March 8, 1965. It was an unpopular war from the start. Those who protested US involvement felt like it wasn’t our war and we shouldn’t be there. Be that as it may, we were there, and for the time being, we weren’t going anywhere. The war was a long one, but on April 30, 1975, it came to an abrupt end, when Saigon fell.

From November 1, 1955 until April 30, 1975, the Vietnam war raged. The United States entered the war on March 8, 1965. It was an unpopular war from the start. Those who protested US involvement felt like it wasn’t our war and we shouldn’t be there. Be that as it may, we were there, and for the time being, we weren’t going anywhere. The war was a long one, but on April 30, 1975, it came to an abrupt end, when Saigon fell.

At dawn that spring morning, communist forces moved into Saigon, where they received only sporadic resistance. The South Vietnamese forces had collapsed under the rapid advancement of the North Vietnamese. The most recent fighting had begun in December 1974. That was when the North Vietnamese launched a major attack against the lightly defended province of Phuoc Long, which was located due north of Saigon along the Cambodian border, overrunning the provincial capital at Phuoc Binh on January 6, 1975. Despite previous promises, from President Nixon, to provide aid if the communists attacked Saigon, the United States did nothing. The problem…Nixon had resigned from office and his successor, Gerald Ford, was unable to convince a hostile Congress to keep Nixon’s earlier promises to rescue Saigon from communist takeover. The United States had its own set of tumultuous circumstances to deal with at that time.

The lack of response from the United States emboldened the North Vietnamese, who launched a new campaign  in March 1975. The South Vietnamese forces fell back in total chaos, and once again, the United States did nothing. The South Vietnamese abandoned Pleiku and Kontum in the Highlands with little to no fighting. Then Quang Tri, Hue, and Da Nang fell to the communist onslaught. The North Vietnamese continued to attack south along the coast toward Saigon, defeating the South Vietnamese forces at each encounter.

in March 1975. The South Vietnamese forces fell back in total chaos, and once again, the United States did nothing. The South Vietnamese abandoned Pleiku and Kontum in the Highlands with little to no fighting. Then Quang Tri, Hue, and Da Nang fell to the communist onslaught. The North Vietnamese continued to attack south along the coast toward Saigon, defeating the South Vietnamese forces at each encounter.

The South Vietnamese 18th Division had fought a valiant battle at Xuan Loc, just to the east of Saigon, destroying three North Vietnamese divisions in the process. They were the only division that seemed capable of continuing the fight. That was to be the last battle in the defense of the Republic of South Vietnam. The South Vietnamese forces held out against the attackers until they ran out of tactical air support and weapons, finally abandoning Xuan Loc to the communists on April 21, 1975.

Having crushed the last major organized opposition before Saigon, the North Vietnamese got into position for the final assault. In Saigon, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu resigned and transferred authority to Vice President Tran Van Huong before fleeing the city on April 25. By April 27, the North Vietnamese had  completely encircled Saigon and began to maneuver for a complete takeover. When they attacked at dawn on April 30, they met little resistance. North Vietnamese tanks crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace and the war came to an end. North Vietnamese Colonel Bui Tin accepted the surrender from General Duong Van Minh, who had taken over after Tran Van Huong and had only spent only one day in power. Tin explained to Minh, “You have nothing to fear. Between Vietnamese there are no victors and no vanquished. Only the Americans have been beaten. If you are patriots, consider this a moment of joy. The war for our country is over.” Of course, this also meant that Vietnam would be a Communist country, like it or not.

completely encircled Saigon and began to maneuver for a complete takeover. When they attacked at dawn on April 30, they met little resistance. North Vietnamese tanks crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace and the war came to an end. North Vietnamese Colonel Bui Tin accepted the surrender from General Duong Van Minh, who had taken over after Tran Van Huong and had only spent only one day in power. Tin explained to Minh, “You have nothing to fear. Between Vietnamese there are no victors and no vanquished. Only the Americans have been beaten. If you are patriots, consider this a moment of joy. The war for our country is over.” Of course, this also meant that Vietnam would be a Communist country, like it or not.

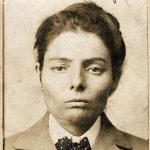

A while back, while looking at historical pictures, I came across one that bore an amazing resemblance to my grandson, Chris Petersen. I realize that a lot of people say that some people remind them of other people, but even my family agreed that this young man looked like Chris at that age. I have no idea who this boy is, or if he is related to Chris, because the picture doesn’t tell his name…just his occupation, which was quite interesting. The boy is, what is known as, a Powder Monkey. I had no idea what that was, and after doing some research on it, I’m thankful that powder monkey is not an occupation we have today, and thankful that my grandson never had the opportunity to be one. To me, it seems like a very dangerous occupation.

A while back, while looking at historical pictures, I came across one that bore an amazing resemblance to my grandson, Chris Petersen. I realize that a lot of people say that some people remind them of other people, but even my family agreed that this young man looked like Chris at that age. I have no idea who this boy is, or if he is related to Chris, because the picture doesn’t tell his name…just his occupation, which was quite interesting. The boy is, what is known as, a Powder Monkey. I had no idea what that was, and after doing some research on it, I’m thankful that powder monkey is not an occupation we have today, and thankful that my grandson never had the opportunity to be one. To me, it seems like a very dangerous occupation.

Powder boys were used during the 17th century on warships. A powder boy or “powder monkey” manned naval artillery guns as a member of a warship’s crew, primarily during the age of sailboats. His chief role was to carry gunpowder from the powder magazine in the ship’s hold to the artillery guns. Sometimes he carried bulk powder and other times he carried cartridges, to minimize the risk of fires and explosions. The function was usually fulfilled by boy seamen of 12 to 14 years of age. Powder monkeys were selected for the job for their speed and height. They needed to be short so they could not be seen, and could move more easily in the limited space between decks, while remaining hidden behind the ship’s gunwale, thereby keeping them from being shot by enemy ships’ sharp shooters. Some women and older men also worked as powder monkeys. I realize that this might have seemed like a good idea, but as a mom and grandma, I would be terribly worried if that were my boy on one of those ships.

While the Royal Navy first began using the term “powder monkey” in the 17th century, it was later used, and  continues to be used in some countries, to signify a skilled technician or engineer who engages in blasting work, such as in the mining or demolition industries. In such industries, a “powder monkey” is also sometimes referred to as a “blaster.” It seems that just about any occupation that carries the name “powder monkey” is a dangerous one. As to the boys who did this work on warships, well…their bravery is amazing. They must have see death around them. They knew the risks. Still, they saw a need, and knew that their contribution would help their country. They were patriots, and as with any soldier, they have my respect. They should never be forgotten, because they were soldiers too…in every way.

continues to be used in some countries, to signify a skilled technician or engineer who engages in blasting work, such as in the mining or demolition industries. In such industries, a “powder monkey” is also sometimes referred to as a “blaster.” It seems that just about any occupation that carries the name “powder monkey” is a dangerous one. As to the boys who did this work on warships, well…their bravery is amazing. They must have see death around them. They knew the risks. Still, they saw a need, and knew that their contribution would help their country. They were patriots, and as with any soldier, they have my respect. They should never be forgotten, because they were soldiers too…in every way.

The long awaited birth of the third child of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge has finally arrived. It’s a prince. I am so excited to have a new royal cousin…my 16th cousin twice removed to be exact. Of course, we don’t know the baby boy’s name yet but he weighed in at 8 pounds 7 ounces, so he was a good sized boy. He is just perfect. It is always so exciting with one of my royal cousins has a new baby. There has been much speculation as to what the couple might name the little prince, with names like James, Phillip, and Arthur. The bookies have started the betting process, so everyone can be involved, Personally I like the names Michael, Phillip and Spencer. In fact I would like a some version of the three together. Time will tell, and until William and Kate inform the Queen of the name, no one else will get to know what it is, but from what I’ve read, the Queen will have no say in the baby’s name. As a grandmother, and soon-to-be great grandmother myself, while I have my own ideas about good baby names, I do not think it is my place to try to force my opinion, and in fact, when I have thought a name would not be the best on for the babies in my family, I have found out that each of their names seem to fit them perfectly. That said, no matter what the name is, it should be totally the decision of William and Kate. We just wish they would hurry up and tell us already!!

The long awaited birth of the third child of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge has finally arrived. It’s a prince. I am so excited to have a new royal cousin…my 16th cousin twice removed to be exact. Of course, we don’t know the baby boy’s name yet but he weighed in at 8 pounds 7 ounces, so he was a good sized boy. He is just perfect. It is always so exciting with one of my royal cousins has a new baby. There has been much speculation as to what the couple might name the little prince, with names like James, Phillip, and Arthur. The bookies have started the betting process, so everyone can be involved, Personally I like the names Michael, Phillip and Spencer. In fact I would like a some version of the three together. Time will tell, and until William and Kate inform the Queen of the name, no one else will get to know what it is, but from what I’ve read, the Queen will have no say in the baby’s name. As a grandmother, and soon-to-be great grandmother myself, while I have my own ideas about good baby names, I do not think it is my place to try to force my opinion, and in fact, when I have thought a name would not be the best on for the babies in my family, I have found out that each of their names seem to fit them perfectly. That said, no matter what the name is, it should be totally the decision of William and Kate. We just wish they would hurry up and tell us already!!

With the birth of this baby boy, history will be made again. This new baby will be 5th in line to the throne of England, following his grandpa, Prince Charles; his dad, Prince William; his brother, Prince George; and his sister, Princess Charlotte. In times past, Charlotte would have fallen after this new baby, but the law changed before her birth, and she now holds her line in the succession to the throne. Many people are not sure how they feel about that, but since her great grandmother, Queen Elizabeth has successfully ruled England for many years, it would be hard to dispute Princess Charlotte’s ability should that position ever arise. This baby also moves Prince Harry, William’s brother, to 6th place in the line of succession, which pretty much guarantees that he will never be the King of England, unless something huge happens, which I pray it never does…obviously.

So, as an eventful first day of life comes to an end for the little prince, who was born of Saint George’s Day, a big holiday in England, we go to sleep still wondering what this little man will be named. Not that he really cares either way right now. After all, he has had a busy day, and all he really wants is dinner and a soft bed. Happy birthday sweet little HRH Prince of Cambridge, which is his official title. We look forward to knowing your name very soon. Congratulations to the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. We are so happy for you!!

Who fired the shot that killed Richthofen? And who was Richthofen anyway? First, Richthofen was also known as the Red Baron. Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen was born on May 2, 1892. He was a fighter pilot with the German Air Force during World War I, and is considered the ace-of-aces of the war. He was officially credited with 80 air combat victories.

Who fired the shot that killed Richthofen? And who was Richthofen anyway? First, Richthofen was also known as the Red Baron. Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen was born on May 2, 1892. He was a fighter pilot with the German Air Force during World War I, and is considered the ace-of-aces of the war. He was officially credited with 80 air combat victories.

Nevertheless, as it goes with fighter pilots, their lives are always in jeopardy, and not all of them will come out of war alive. Such was the case with the Red Baron. The end came for him on April 21, 1918. It’s possible that he made mistakes on that final flight. Richthofen was a highly experienced and skilled fighter pilot, who was fully aware of the risk from ground fire. Furthermore, he concurred with the rules of air fighting created by his late mentor Boelcke, who specifically advised pilots not to take unnecessary risks. With that in mind, one must wonder if Richthofen’s judgement during his last combat was unsound or somehow compromised.

Several theories have been proposed to account for his behavior. In 1999, a German medical researcher, Henning Allmers, published an article in the British medical journal The Lancet, suggesting it was likely that brain damage from the head wound Richthofen suffered in July 1917, played a part in the Red Baron’s death. This was supported by a 2004 paper by researchers at the University of Texas. Richthofen’s behavior after his injury was noted as consistent with brain-injured patients, and such an injury could account for his perceived lack of judgement on his final flight…a flight in which he was flying too low over enemy territory and suffering target fixation, which is an attentional phenomenon observed in humans in which an individual becomes so focused on an observed object, that they inadvertently increase their risk of colliding with the object.

Still, the biggest question is not why the Red Baron made the mistake that would get him killed, but rather who killed him. The RAF credited Arthur Roy Brown, an RNAS lieutenant with shooting down the Red Baron, but it is  now generally agreed that the bullet that hit the Red Baron was fired from the ground. The Red Baron died following an extremely serious and inevitably fatal chest wound from a single bullet, penetrating from the right armpit and resurfacing from his left chest. Brown’s attack was from behind and above, and from Red Baron’s left. Even more conclusively, Red Baron could not have continued his pursuit for as long as he did…up to two minutes…had this wound come from Brown’s guns. Brown himself never spoke much about what happened that day, claiming, “There is no point in me commenting, as the evidence is already out there.”

now generally agreed that the bullet that hit the Red Baron was fired from the ground. The Red Baron died following an extremely serious and inevitably fatal chest wound from a single bullet, penetrating from the right armpit and resurfacing from his left chest. Brown’s attack was from behind and above, and from Red Baron’s left. Even more conclusively, Red Baron could not have continued his pursuit for as long as he did…up to two minutes…had this wound come from Brown’s guns. Brown himself never spoke much about what happened that day, claiming, “There is no point in me commenting, as the evidence is already out there.”

Many sources, including a 1998 article by Geoffrey Miller, a physician and historian of military medicine, and a 2002 British Channel 4 documentary, have suggested that Sergeant Cedric Popkin was the person most likely to have killed Richthofen. Popkin was an anti-aircraft (AA) machine gunner with the Australian 24th Machine Gun Company, and was using a Vickers gun. He fired at Richthofen’s aircraft on two occasions…first as the Baron was heading straight at his position, and then at long range from the right. Given the nature of Richthofen’s wounds, Popkin was in a position to fire the fatal shot, when the pilot passed him for a second time, on the right. Some confusion has been caused by a letter that Popkin wrote, in 1935, to an Australian official historian. It stated Popkin’s belief that he had fired the fatal shot as Red Baron flew straight at his position. In the latter respect, Popkin was incorrect. The bullet that caused the Baron’s death came from the side.

A 2002 Discovery Channel documentary suggests that Gunner W. J. “Snowy” Evans, a Lewis machine gunner with the 53rd Battery, 14th Field Artillery Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery is likely to have killed Red Baron.  Miller and the Channel 4 documentary dismiss this theory, because of the angle from which Evans fired at Richthofen.

Miller and the Channel 4 documentary dismiss this theory, because of the angle from which Evans fired at Richthofen.

Other sources have suggested that Gunner Robert Buie, also of the 53rd Battery, may have fired the fatal shot. There is little support for this theory. In 2007, a municipality in Sydney recognized Buie as the man who shot down Richthofen, placing a plaque near Buie’s former home. Buie, who died in 1964, has never been officially recognized in any other way. I suppose that, in reality, we will never really know for sure who killed Red Baron, but the theories present an interesting puzzle, and one that will most likely never be solved.

The Gallipoli campaign took place between April 1915 and December 1915 in an effort to take the Dardanelles from the Turkish Ottoman Empire…an ally of Germany and Austria, and thus force it out of the war. About 60,000 Australians and 18,000 New Zealanders were part of a larger British force. Among the wounded were some 26,000 Australians and 7,571 New Zealanders, while 7,594 Australians and 2,431 New Zealanders were killed. Numerically, Gallipoli was a minor campaign, but it took on considerable national and personal importance to the Australians and New Zealanders who fought there.

The Gallipoli campaign took place between April 1915 and December 1915 in an effort to take the Dardanelles from the Turkish Ottoman Empire…an ally of Germany and Austria, and thus force it out of the war. About 60,000 Australians and 18,000 New Zealanders were part of a larger British force. Among the wounded were some 26,000 Australians and 7,571 New Zealanders, while 7,594 Australians and 2,431 New Zealanders were killed. Numerically, Gallipoli was a minor campaign, but it took on considerable national and personal importance to the Australians and New Zealanders who fought there.

The Gallipoli Campaign was Australia’s and New Zealand’s introduction to the Great War. Many Australians and New Zealanders fought on the Peninsula from the day of the landings (April 25, 1915) until the evacuation on December 20, 1915. The 25th April is the New Zealand equivalent of Armistice Day and is marked as the ANZAC day in both countries with Dawn Parades and  other services in every city and town. Shops are closed in the morning. It is a very important day to Australians and New Zealanders for a variety of reasons that have changed and transmuted over the years. This campaign, while small in losses, was huge in the hearts of the Australians and New Zealanders.

other services in every city and town. Shops are closed in the morning. It is a very important day to Australians and New Zealanders for a variety of reasons that have changed and transmuted over the years. This campaign, while small in losses, was huge in the hearts of the Australians and New Zealanders.

While many losses came out of this campaign, it seems that there were two who were saved…potentially anyway. After the campaign was over, and people were wandering the area, someone came across an unusual, and seriously rare, find. There on the ground were two bullets that had collided with each other in mid-air, thus saving the lives of the two combatants who fired the rounds. Obviously, they could have been hit by another round, in which case the mid-air collision only slightly prolonged their lives. At least this scenario might be what you would think. The reality is that you would be wrong. Taking a look closer at the bullets, it is quite obvious that one round collided with  another. But the round on the left doesn’t have any rifling on it, whereas the round on the right does. They collided, but in reality, the round on the left probably wasn’t moving as fast as an actual speeding bullet. Maybe it was part of a clip on an ANZAC soldiers webgear as he was in an attack, or some other bizarre reason. But this most certainly wasn’t the intersection of two trajectories between the lines…making such a collision between two bullets even more rare. Nevertheless, the picture itself is quite interesting, and would have caught the eye of anyone looking at it. How they got there really makes no difference, but the fact that they were found on the Gallipoli battlefield makes them an interesting find. If you ask me, it is still a very rare occurrence.

another. But the round on the left doesn’t have any rifling on it, whereas the round on the right does. They collided, but in reality, the round on the left probably wasn’t moving as fast as an actual speeding bullet. Maybe it was part of a clip on an ANZAC soldiers webgear as he was in an attack, or some other bizarre reason. But this most certainly wasn’t the intersection of two trajectories between the lines…making such a collision between two bullets even more rare. Nevertheless, the picture itself is quite interesting, and would have caught the eye of anyone looking at it. How they got there really makes no difference, but the fact that they were found on the Gallipoli battlefield makes them an interesting find. If you ask me, it is still a very rare occurrence.

Stagecoach drivers like Charley Parkhurst were tough as nails. Not everyone could handle a stagecoach. The stagecoach driver was respected…sometimes even more than was the millionaire statesman who might be riding beside him, or anyone else who had been given that honor. Parkhurst had been through the good times and bad times of driving stagecoach. Twice, Charley was held up. The first time, he was forced to throw down his strongbox because he was unarmed. The second time, he was prepared. When a road agent ordered the stage to stop and commanded Charley to throw down its strongbox, Parkhurst leveled a shotgun blast into the chest of the outlaw, whipped his horses into a full gallop, and left the bandit in the road.

Stagecoach drivers like Charley Parkhurst were tough as nails. Not everyone could handle a stagecoach. The stagecoach driver was respected…sometimes even more than was the millionaire statesman who might be riding beside him, or anyone else who had been given that honor. Parkhurst had been through the good times and bad times of driving stagecoach. Twice, Charley was held up. The first time, he was forced to throw down his strongbox because he was unarmed. The second time, he was prepared. When a road agent ordered the stage to stop and commanded Charley to throw down its strongbox, Parkhurst leveled a shotgun blast into the chest of the outlaw, whipped his horses into a full gallop, and left the bandit in the road.

Charley Parkhurst was one of the more skillful stagecoach drivers, not only in  California, but throughout the west. He was often called “One-eyed” or “Cockeyed” Charley, because he had lost an eye when kicked by a horse. He drove a stagecoach in California for 20 years. One-eyed Charley was known as one of the toughest, roughest, and the most daring of all stagecoach drivers. Like most drivers, he was proud of his skill in the extremely difficult job as “whip.” A “whip” is what stagecoach drivers were often called. Proper handling of the horses and the great coaches was an art that required much practice, experience, and not the least, courage. Whips received high salaries for the times, sometimes as much as $125 a month, plus room and board. While most stage drivers were sober, at least while on duty, nearly all were fond of an occasional “eye opener.” A good driver was the captain of his craft. His timid passengers feared him. He was

California, but throughout the west. He was often called “One-eyed” or “Cockeyed” Charley, because he had lost an eye when kicked by a horse. He drove a stagecoach in California for 20 years. One-eyed Charley was known as one of the toughest, roughest, and the most daring of all stagecoach drivers. Like most drivers, he was proud of his skill in the extremely difficult job as “whip.” A “whip” is what stagecoach drivers were often called. Proper handling of the horses and the great coaches was an art that required much practice, experience, and not the least, courage. Whips received high salaries for the times, sometimes as much as $125 a month, plus room and board. While most stage drivers were sober, at least while on duty, nearly all were fond of an occasional “eye opener.” A good driver was the captain of his craft. His timid passengers feared him. He was  held in awe by stable boys, and was the trusty agent of his employer…and Charley was the best.

held in awe by stable boys, and was the trusty agent of his employer…and Charley was the best.

Nevertheless, little was really known about Charley Parkhurst before or after he came to California. It wasn’t until his body was prepared for burial that his true secret was discovered. Charlotte “Charley” Parkhurst was a woman. One doctor claimed that at some point in her life, she had been a mother. Unknowingly, Parkhurst could claim a national first. After voting on Election Day, November 3, 1868, Charley was probably the first woman to cast a ballot in any election. It wasn’t until 52 years later that the right to vote was guaranteed to women by the nineteenth amendment.

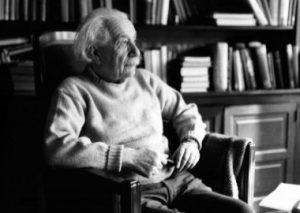

For many years, I have admired Albert Einstein. His mind and his level of intelligence intrigued me, as did his quirkiness. When you think of a genius, your mind automatically produces a picture of a very organized person, who is able to handle any situation, but even geniuses have their issues with things. One well know “weakness” for Einstein was the fact that if something can be written down, it need not take up space in his brain. His brain was very full after all, and clutter was always an issue. That said, if he couldn’t find his train ticket…for the train he took every day from home to work and back…he didn’t know at which stop to get off, because he relied on his ticket to tell him that. I don’t think most of us could even begin to filter our brain in such a way…but Einstein could, and did.

For many years, I have admired Albert Einstein. His mind and his level of intelligence intrigued me, as did his quirkiness. When you think of a genius, your mind automatically produces a picture of a very organized person, who is able to handle any situation, but even geniuses have their issues with things. One well know “weakness” for Einstein was the fact that if something can be written down, it need not take up space in his brain. His brain was very full after all, and clutter was always an issue. That said, if he couldn’t find his train ticket…for the train he took every day from home to work and back…he didn’t know at which stop to get off, because he relied on his ticket to tell him that. I don’t think most of us could even begin to filter our brain in such a way…but Einstein could, and did.

Einstein was a gifted scientist and mathematician. He was most famous for his theory of relativity and the resulting formula relating mass and energy…E = MC². He was the winner of 1921 Nobel Prize in physics for his work on the photoelectric effect, which is also known as the Hertz effect. Einstein was born in Ulm, in the Kingdom of Württemberg in the German Empire, on March 14, 1879. His parents were Hermann Einstein, a salesman and engineer, and Pauline Koch. He didn’t feel the need to celebrate his birthday,saying “It is a known fact that I was born, and that is all that is necessary.” Friends, colleagues and complete strangers still felt the need to send telegrams, cards, letters, gifts, and an elaborate birthday cake.

Being a Jewish man, circumstances in Germany became life threatening for Einstein in the early 1930s, so early in 1933, while on a trip to the United States, he knew he could not go home again, so he moved permanently  to the United States, and worked at Princeton University…a career that would take him to the end of his life on April 18, 1955. Einstein could have been saved, but when he was asked if he wanted to undergo surgery, he refused, saying, “I want to go when I want to go. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.” After an autopsy, Einstein’s body was cremated and his ashes spread in an undisclosed location.

to the United States, and worked at Princeton University…a career that would take him to the end of his life on April 18, 1955. Einstein could have been saved, but when he was asked if he wanted to undergo surgery, he refused, saying, “I want to go when I want to go. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.” After an autopsy, Einstein’s body was cremated and his ashes spread in an undisclosed location.

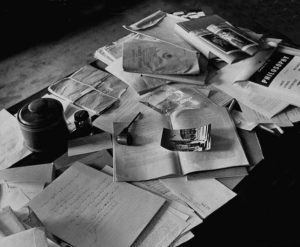

After his passing, another of the multiple quirky aspects of Einstein’s personality came to light when LIFE magazine wrote about a famous picture taken in Albert Einstein’s Princeton office. Einstein’s desk was just as he left it. Here, the picture says, is where Einstein worked, dreamed, lived his singular, principled life to its fullest. “When I was young, all I wanted and expected from life was to sit quietly in some corner doing my work without the public paying attention to me,” said Einstein after being honored at a social function. “And now see what has become of me.”

When I look and Einstein’s desk, it takes me back to the many times my own desk has looked exactly like that. It is another way that the famed scientific and mathematical genius and I are alike. Now, I do not claim to have the IQ of this man, but we do have a few things in common, and the ability to work on top of a stack of papers seems to be one of them. Maybe that and the ability to somewhat filter things out of my mind if they are stored in my phone which could be the same thing as filtering because I have it written down. And because of my shy side, I suppose I can understand his concern over public attention, and yet knowing that sometimes it can’t be helped. When I look at his desk, I can see a man whose mind was fill with many thoughts, making it easy to  lose himself in his thoughts to the point of seeming to ignore those around him. Those who met Einstein recalled his human side. He “walked to work or rode the bus in bad weather; visited the neighbors’ newborn kittens; greeted carolers on winter nights; refused to update his eyeglass prescription; and declined to wear socks because they would get holes in them. But he didn’t seem to mind fuzzy slippers!” He was his own man with his own ideas, and if those ideas didn’t make sense to those around him, it was simply not his problem. On April 18, 1955, Albert Einstein died soon after a blood vessel burst near his heart. The world mourned Einstein’s death, but true to form, at his request, his office and house were not turned into memorials.

lose himself in his thoughts to the point of seeming to ignore those around him. Those who met Einstein recalled his human side. He “walked to work or rode the bus in bad weather; visited the neighbors’ newborn kittens; greeted carolers on winter nights; refused to update his eyeglass prescription; and declined to wear socks because they would get holes in them. But he didn’t seem to mind fuzzy slippers!” He was his own man with his own ideas, and if those ideas didn’t make sense to those around him, it was simply not his problem. On April 18, 1955, Albert Einstein died soon after a blood vessel burst near his heart. The world mourned Einstein’s death, but true to form, at his request, his office and house were not turned into memorials.

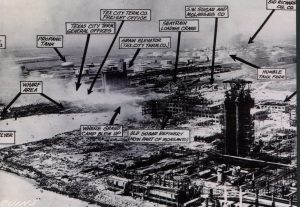

It was a typical day in Texas City, Texas…a port city in Galveston Bay. April was always warm, in the mid-70s, so it was perfect outdoor weather. Fires around the docks were a fairly common occurrence in Texas City, and it was not unusual for residents to travel down to the docks to watch the fires and the firemen working. Fires tend to attract the casual observer as well as the local news agencies. This day started out just as any other typical Texas day, but all that would change very soon. On the morning of April 16, 1947 a fire broke out on the S.S. Grandcamp. The fire produced a dense, brilliantly colored smoke that could be seen all over town. On board Grandcamp, among other things, was a supply of ammonium nitrate, which was producing the brilliant colors. The ship was docked in the Texas City port, so the smoke could be seen all over town. This fire, like any other, brought anybody who had any free time down to the dock to watch the action. This would be a fatal mistake for many of the bystanders.

It was a typical day in Texas City, Texas…a port city in Galveston Bay. April was always warm, in the mid-70s, so it was perfect outdoor weather. Fires around the docks were a fairly common occurrence in Texas City, and it was not unusual for residents to travel down to the docks to watch the fires and the firemen working. Fires tend to attract the casual observer as well as the local news agencies. This day started out just as any other typical Texas day, but all that would change very soon. On the morning of April 16, 1947 a fire broke out on the S.S. Grandcamp. The fire produced a dense, brilliantly colored smoke that could be seen all over town. On board Grandcamp, among other things, was a supply of ammonium nitrate, which was producing the brilliant colors. The ship was docked in the Texas City port, so the smoke could be seen all over town. This fire, like any other, brought anybody who had any free time down to the dock to watch the action. This would be a fatal mistake for many of the bystanders.

The ammonium nitrate on board the Grandcamp detonated at 9:12 am, blowing he ship apart and sending the cargo of peanuts, tobacco, twine, bunker oil and the remaining bags of ammonium nitrate 2,000 to 3,000 feet into the air. Fireballs streaked across the sky and could be seen for miles across Galveston Bay as molten ship fragments erupted out of the pier. The blast sent a fifteen foot tidal wave crashing onto the dock and flooding the surrounding area. Windows were shattered in Houston, 40 miles to the north, and people in Louisiana felt the shock 250 miles away. Most of the buildings closest to the blast were flattened, and there were many more that had doors and roofs blown off. The Monsanto plant which was only three hundred feet away, was destroyed by the blast. Most of the Texas City Terminal Railways’ warehouses along the docks were destroyed. Hundreds of employees, pedestrians and bystanders were killed. At the time of the Grandcamp’s explosion, only two additional vessels were docked in port…the S.S. High Flyer and the Wilson B. Keene, both American C-2 cargo ships similar to the Grandcamp.

The intensity of the blast sent shrapnel tearing into the surrounding area. Flaming debris ignited giant tanks full  of oil and chemicals stored at the refineries, causing a set of secondary fires and smaller explosions. The Longhorn II, a barge anchored in port, was lifted out of the water by the sheer force of the explosion and landed 100 feet away on the shore. Buildings blazed long after the initial explosion, provoking large scale emergency relief efforts throughout the day, that night, and into the following day. The fires in nearby industrial buildings and chemical plants spread the destruction even farther. The chief and 27 firefighters from the Texas City Fire Department were killed in the initial blast. Official estimates put the death toll at 567 and injuries at more than 5,000. Some of the dead were never identified, and some may never have been found at all.

of oil and chemicals stored at the refineries, causing a set of secondary fires and smaller explosions. The Longhorn II, a barge anchored in port, was lifted out of the water by the sheer force of the explosion and landed 100 feet away on the shore. Buildings blazed long after the initial explosion, provoking large scale emergency relief efforts throughout the day, that night, and into the following day. The fires in nearby industrial buildings and chemical plants spread the destruction even farther. The chief and 27 firefighters from the Texas City Fire Department were killed in the initial blast. Official estimates put the death toll at 567 and injuries at more than 5,000. Some of the dead were never identified, and some may never have been found at all.

The blast registered on a seismograph as far away as Denver, Colorado. Dockworker Pete Suderman remembers flying thirty feet as the blast carried him and several of the dock’s three-inch wooden planks across the pier. Nattie Morrow was in her home with her two children and sister-in-law Sadie. She watched the billowing smoke near the Monsanto plant from her back porch just prior to the blast. “Suddenly a thundering boom sounded, and seconds later the door ripped off its facing, skidded across the kitchen floor, and slammed down onto the table where I sat with the baby. The house toppled to one side and sat off its piers at a crazy angle. Broken glass filled the air, and we didn’t know what was happening.”

At the time of the explosion, phone services in Texas City were not working because of a telephone operators’ strike. When the operators learned of the accident, they quickly went back to work, but the strike caused an initial delay in coordinating rescue efforts. Once operators began calling for help, rescue workers from all over the area began responding immediately. The U.S. Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marine Reserve and the Texas National Guard all sent personnel, including doctors, nurses and ambulances. The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston sent doctors, nurses, and medical students. Firefighters from Galveston, Houston, Fort Crockett, Ellington Field, and surrounding towns arrived to help. The cities of Galveston, Houston and San Antonio sent policemen to assist the Texas City Police Department in maintaining order after the explosion. The U.S. Army flew in blood  plasma, gas masks, food, and other supplies, provided bull-dozers to begin clearing the wreckage, and set up temporary housing for the survivors at Camp Wallace in Hitchcock. The Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America sent a flood of volunteers who provided first aid, food, water and comfort to city residents. Volunteers from other local organizations, and others who were not part of any organization, felt compelled to help. There was no operational hospital in Texas City at the time of the disaster, so volunteers converted city hall and chamber of commerce buildings into makeshift infirmaries. Many wounded were evacuated to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, the hospital at Fort Crockett, and hospitals in Houston.

plasma, gas masks, food, and other supplies, provided bull-dozers to begin clearing the wreckage, and set up temporary housing for the survivors at Camp Wallace in Hitchcock. The Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America sent a flood of volunteers who provided first aid, food, water and comfort to city residents. Volunteers from other local organizations, and others who were not part of any organization, felt compelled to help. There was no operational hospital in Texas City at the time of the disaster, so volunteers converted city hall and chamber of commerce buildings into makeshift infirmaries. Many wounded were evacuated to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, the hospital at Fort Crockett, and hospitals in Houston.

On April 10, 1912, Titanic set sail from Southampton. Titanic called at Cherbourg in France and Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland before heading west to New York. For the passengers and crew, Titanic was the ultimate in luxury, and to be on it was the ultimate thrill. The ship was the most luxurious ship of its day, and to add to their sense of excitement, it was unsinkable. The passengers were assured that the ship had so many fail-safes in place that the builders didn’t even think the lifeboats were necessary, and any that were considered to be in the way, were removed, in what would prove to be a fatal mistake. In the end, there were 20 lifeboats on board the ship, when she was supposed to have 64 lifeboats. Each had a capacity of 65 people. Most lifeboats were lowered to the water with less than half their actual capacity.

On April 10, 1912, Titanic set sail from Southampton. Titanic called at Cherbourg in France and Queenstown (now Cobh) in Ireland before heading west to New York. For the passengers and crew, Titanic was the ultimate in luxury, and to be on it was the ultimate thrill. The ship was the most luxurious ship of its day, and to add to their sense of excitement, it was unsinkable. The passengers were assured that the ship had so many fail-safes in place that the builders didn’t even think the lifeboats were necessary, and any that were considered to be in the way, were removed, in what would prove to be a fatal mistake. In the end, there were 20 lifeboats on board the ship, when she was supposed to have 64 lifeboats. Each had a capacity of 65 people. Most lifeboats were lowered to the water with less than half their actual capacity.

The night of April 14, 1912 was very cold, and the route Titanic was on was littered with icebergs. Other ships  in the area tried to warn Titanic, but the radio operator of Titanic did not take the warnings seriously. He was operating under the mistaken idea that Titanic could sail right through any ice field she might come upon, and have no problems whatsoever. The radio operator was wrong. Nevertheless, he shut of the radio after the 6th warning transmission. The iceberg strike came at 11:40 pm…but the first distress call was sent almost an hour later and even then the ships receiving the calls could did not believe it could be real. Finally, at 12:40 am, Carpathia’s radio operator gave the call to head for Titanic’s last known position.

in the area tried to warn Titanic, but the radio operator of Titanic did not take the warnings seriously. He was operating under the mistaken idea that Titanic could sail right through any ice field she might come upon, and have no problems whatsoever. The radio operator was wrong. Nevertheless, he shut of the radio after the 6th warning transmission. The iceberg strike came at 11:40 pm…but the first distress call was sent almost an hour later and even then the ships receiving the calls could did not believe it could be real. Finally, at 12:40 am, Carpathia’s radio operator gave the call to head for Titanic’s last known position.

Help would come too late for Titanic. By 2:20 am on April 15, 1912, Titanic sank, but she was not without her heroes. As the Titanic was sinking, the deck crew began loading passengers onto lifeboats. The engineering crew stayed at their posts to work the pumps, controlling flooding as much as possible. This action ensured the  power stayed on during the evacuation and allowed the wireless radio system to keep sending distress calls. These men bravely kept at their work and helped save more than 700 people…even though it would cost them their own lives. When Titanic went down, she took with her 1500 people. of those, 688 were crew members, including all 25 of the engineers who worked tirelessly, at their own peril to buy what little bit of time they could for the passengers in their care. Many of the crew members forfeited their lives so that the passengers might live. Were serious mistakes made…yes, of course, but by the same token, the sinking of Titanic saw some of the most amazing bravery ever.

power stayed on during the evacuation and allowed the wireless radio system to keep sending distress calls. These men bravely kept at their work and helped save more than 700 people…even though it would cost them their own lives. When Titanic went down, she took with her 1500 people. of those, 688 were crew members, including all 25 of the engineers who worked tirelessly, at their own peril to buy what little bit of time they could for the passengers in their care. Many of the crew members forfeited their lives so that the passengers might live. Were serious mistakes made…yes, of course, but by the same token, the sinking of Titanic saw some of the most amazing bravery ever.