History

Tornado warnings and warning sirens are things that just about every person knows about these days, but in 1944, they weren’t available at all. It wasn’t that no one had thought about a tornado warning system, but rather that they had and they decided against it,and so nothing was developed. If you’re like me, you wonder why anyone would think it a bad idea to warn people about the possibility of a tornado, but that was exactly what happened. According to a report titled “The History (and Future) of Tornado Warning Dissemination in the United States” by Timothy A. Coleman, Kevin R. Knupp, James Spann, J. B. Elliott, and Brian E. Peters, “Despite promising research on the conditions that are favorable for tornadoes in the 1880s by John P. Finley, a general consensus was reached among scientists in the 1880s and 1890s that tornado forecasts and warnings would cause more harm than good. A ban was placed on the issuance of tornado warnings from 1887, when the U.S. Army Signal Corps handled weather forecasts, until 1938, when the civilian U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) finally lifted the ban.” Even after the an was lifted, warnings were pretty primitive. Modern tornado warning really took off and began to develop in 1948…too late for the people of West Virginia and Pennsylvania on June 23, 1944.

Tornado warnings and warning sirens are things that just about every person knows about these days, but in 1944, they weren’t available at all. It wasn’t that no one had thought about a tornado warning system, but rather that they had and they decided against it,and so nothing was developed. If you’re like me, you wonder why anyone would think it a bad idea to warn people about the possibility of a tornado, but that was exactly what happened. According to a report titled “The History (and Future) of Tornado Warning Dissemination in the United States” by Timothy A. Coleman, Kevin R. Knupp, James Spann, J. B. Elliott, and Brian E. Peters, “Despite promising research on the conditions that are favorable for tornadoes in the 1880s by John P. Finley, a general consensus was reached among scientists in the 1880s and 1890s that tornado forecasts and warnings would cause more harm than good. A ban was placed on the issuance of tornado warnings from 1887, when the U.S. Army Signal Corps handled weather forecasts, until 1938, when the civilian U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) finally lifted the ban.” Even after the an was lifted, warnings were pretty primitive. Modern tornado warning really took off and began to develop in 1948…too late for the people of West Virginia and Pennsylvania on June 23, 1944.

On that June 23rd in 1944, a series of tornadoes across West Virginia and Pennsylvania kill more than 150 people. Most of the twisters were classified as F3, but the most deadly one was an F4 on the Fujita scale, meaning it was a devastating tornado, with winds in excess of 207 miles per hour. The afternoon was very hot, when atmospheric conditions suddenly changed and the tornadoes began to form in Maryland. At about 5:30 pm, an F3 tornado, with winds between 158 and 206 miles per hour, struck in western Pennsylvania. That storm killed two people. Just Forty-five minutes later, a very large twister began in West Virginia, and moved into Pennsylvania. It then tracked back to West Virginia. By the time this F4 tornado ended, it had killed 151 people and leveled hundreds of homes. Another tornado struck that afternoon at a YMCA camp in Washington, Pennsylvania. A letter written by a camper was later found 100 miles away. Area Coal-mining towns were also hit hard on June 23rd. There were some reports that a couple of tornadoes actually crossed the Appalachian mountain range, going up one side and coming down the other…a very rare event with any mountain. Finally, about 10 pm, the remarkable series of twisters finally ended, after the last one hit in Tucker County, West Virginia. In all, the storms caused the  destruction of thousands of structures and millions of dollars in damages, and that was just the monetary losses.

destruction of thousands of structures and millions of dollars in damages, and that was just the monetary losses.

While there isn’t much that can be done to spare property in the path of tornadoes, an early warning, and the appropriate action taken, can save the lives of hundreds of people. Sadly, early warnings were not available to save the 153 people killed in the tornado outbreak of June 23, 1944. They were still in the works, because of all the years wasted when scientists decided it was not in the public’s best interest to know about tornadoes. I’m really thankful that the ban was lifted and we have these necessary warnings these days.

On June 22, 1962, an Air France Boeing 707 crashed on the island of Guadeloupe, killing all 113 passengers and crew members aboard. It was one of five major accidents involving Boeing 707s during that year. In all, the five crashes that year killed 457 people. Crashes happen, and unfortunately, they are not always such an unusual occurrence. Nevertheless, there was a mystery involved here. The Boeing 707 was originally a KC-135 military tanker and bomber. Boeing later decided to modify it to be used for civilian transport, and the finished product was the Boeing 707. The new design proved very popular in the commercial aviation industry. The Boeing 707 was not a fuel efficient as some of the other planes of that era, but it was faster than any other commercial jet at that time, so it made up for the fuel problem with its greater speed.

On June 22, 1962, an Air France Boeing 707 crashed on the island of Guadeloupe, killing all 113 passengers and crew members aboard. It was one of five major accidents involving Boeing 707s during that year. In all, the five crashes that year killed 457 people. Crashes happen, and unfortunately, they are not always such an unusual occurrence. Nevertheless, there was a mystery involved here. The Boeing 707 was originally a KC-135 military tanker and bomber. Boeing later decided to modify it to be used for civilian transport, and the finished product was the Boeing 707. The new design proved very popular in the commercial aviation industry. The Boeing 707 was not a fuel efficient as some of the other planes of that era, but it was faster than any other commercial jet at that time, so it made up for the fuel problem with its greater speed.

The airport on the island of Guadeloupe is located in a valley that is surrounded by mountains. Guadeloupe is a part of the French West Indies,located in the Caribbean. This particular airport is not the pilots favorite, because it requires them to make a steep descent just prior to landing. Any problem that occurs in the descent, is very hard to correct, because there is just no time. On June 22, the Air France flight failed to descend correctly and crashed directly into a peak call Dos D’Ane, or the Donkey’s Back. The plane exploded in a fireball; there were no survivors. The flight occurred before the black box flight recorder was invented, so no sure reason for the crash was ever officially found.

This crash was the third deadly crash of a Boeing 707 in a month, so something had to be done. On May 22nd, 45 people died when a plane went down in Missouri and on June 3rd, another Air France 707 crashed in Paris killing 130 people. No evidence was ever found that connected the accidents. It is believed that the weather played a part in the June 22, 1962 crash. The weather was poor in Guadeloupe that day. A violent thunderstorm was in the area, with a low cloud ceiling. Adding to the problem, the VOR navigational beacon  was out of service. The crew reported themselves over the non-directional beacon (NDB) at 5,000 feet and turned east to begin the final approach. That was the last time that anything was “normal” with the flight. Due to incorrect automatic direction finder (ADF) readings caused by the thunderstorm, the plane strayed 9.3 mile west from the procedural let-down track. Moments later, the plane crashed in a forest on the hill called Dos D’Ane, at about 1,400 feet and then exploded. There were no survivors. Among the dead was French Guianan politician and war hero Justin Catayée and poet and black-consciousness activist Paul Niger. While weather played a significant part in the crash, it was not the only cause.

was out of service. The crew reported themselves over the non-directional beacon (NDB) at 5,000 feet and turned east to begin the final approach. That was the last time that anything was “normal” with the flight. Due to incorrect automatic direction finder (ADF) readings caused by the thunderstorm, the plane strayed 9.3 mile west from the procedural let-down track. Moments later, the plane crashed in a forest on the hill called Dos D’Ane, at about 1,400 feet and then exploded. There were no survivors. Among the dead was French Guianan politician and war hero Justin Catayée and poet and black-consciousness activist Paul Niger. While weather played a significant part in the crash, it was not the only cause.

These days, at least in Wyoming, the news is often full of new eruption stories pertaining to Steamboat Geyser in Yellowstone National Park. Steamboat Geyser was dormant from 1911 to 1961. Eleven eruptions were noted between June 4, 1990 and September 23, 2014. Then beginning on March 15, 2018, we have seen a sudden increase in eruptions. Beginning on March 15th, there have been ten eruptions to date…just over three months. That is unheard of for this geyser in recorded history. In reality, it can do what Kilauea has done on Hawaii’s Big Island, only much bigger, because the geyser field in Yellowstone National Park lies on top of an active volcano, with multiple chambers of magma from deep beneath the earth. The same energy that causes geysers to blow could spew an ash cloud as far as Chicago and Los Angeles.

These days, at least in Wyoming, the news is often full of new eruption stories pertaining to Steamboat Geyser in Yellowstone National Park. Steamboat Geyser was dormant from 1911 to 1961. Eleven eruptions were noted between June 4, 1990 and September 23, 2014. Then beginning on March 15, 2018, we have seen a sudden increase in eruptions. Beginning on March 15th, there have been ten eruptions to date…just over three months. That is unheard of for this geyser in recorded history. In reality, it can do what Kilauea has done on Hawaii’s Big Island, only much bigger, because the geyser field in Yellowstone National Park lies on top of an active volcano, with multiple chambers of magma from deep beneath the earth. The same energy that causes geysers to blow could spew an ash cloud as far as Chicago and Los Angeles.

It’s strange to think about the fact that Yellowstone National Park lies on such a huge volcano, and yet three extremely large explosive eruptions have occurred at Yellowstone in the past 2.1 million years with a recurrence  interval of about 600,000 to 800,000 years. More frequent eruptions of basalt and rhyolite lava flows have occurred before and after the large caldera-forming events. It is said that if the Yellowstone volcano erupted again, it it would be catastrophic, but with the chances of a supervolcanic paroxysm being currently around one-in-730,000, it is less likely than a catastrophic asteroid impact. I guess Wyomingites can breathe a little easier. Nevertheless, scientists do want to know what’s behind the most recent activity at Steamboat Geyser. “We see gas emissions. We see all kinds of thermal activity. That’s what Yellowstone does. That’s what it’s supposed to do. It’s one of the most dynamic places on earth,” said Mike Poland, the scientist in charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory.

interval of about 600,000 to 800,000 years. More frequent eruptions of basalt and rhyolite lava flows have occurred before and after the large caldera-forming events. It is said that if the Yellowstone volcano erupted again, it it would be catastrophic, but with the chances of a supervolcanic paroxysm being currently around one-in-730,000, it is less likely than a catastrophic asteroid impact. I guess Wyomingites can breathe a little easier. Nevertheless, scientists do want to know what’s behind the most recent activity at Steamboat Geyser. “We see gas emissions. We see all kinds of thermal activity. That’s what Yellowstone does. That’s what it’s supposed to do. It’s one of the most dynamic places on earth,” said Mike Poland, the scientist in charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory.

Steamboat Geyser is the least predictable geyser in all of Yellowstone National Park. It could erupt in five  minutes, five years, or even 50 years from now. Yet no one visiting Yellowstone wants to turn away from the sight. “That would be the chance of a lifetime,” one visitor said. “I would be amazed.” Steamboat Geyser,is the world’s tallest and far more powerful than Old Faithful, and right now, it’s roaring back to life. Still, timing is everything, and only a few people get to see it. Poland’s team of volcanologists are using thermal-imaging equipment to track the temperature of the 50-mile-wide magma field. They also monitor 28 seismographs since a super volcano would include major earthquake activity. So far,there is no indication that this is anything other than an unusual series of eruptions, and not indication of increased volcanic activity, which puts many people’s minds at ease. The geyser is welcome to continue erupting, but I say, “Just leave that volcano alone.”

minutes, five years, or even 50 years from now. Yet no one visiting Yellowstone wants to turn away from the sight. “That would be the chance of a lifetime,” one visitor said. “I would be amazed.” Steamboat Geyser,is the world’s tallest and far more powerful than Old Faithful, and right now, it’s roaring back to life. Still, timing is everything, and only a few people get to see it. Poland’s team of volcanologists are using thermal-imaging equipment to track the temperature of the 50-mile-wide magma field. They also monitor 28 seismographs since a super volcano would include major earthquake activity. So far,there is no indication that this is anything other than an unusual series of eruptions, and not indication of increased volcanic activity, which puts many people’s minds at ease. The geyser is welcome to continue erupting, but I say, “Just leave that volcano alone.”

When we think of deployment, we think of the military and of war, but there are other ways to be deployed too, and some of them do not even include the military. Every year, thousands of firefighters are separated from their family members, some of them for months at a time. For the most part, these are wildland firefighters, but sometimes they even have to enlist the help of teams from cities around the country. Wildland fires are not bound by the schedules of humans. Once they get going, they take on a life of their own. Firefighters are in it for the long haul, and many wildland firefighters go from fire to fire, spending the entire fire season far away from their families.

When we think of deployment, we think of the military and of war, but there are other ways to be deployed too, and some of them do not even include the military. Every year, thousands of firefighters are separated from their family members, some of them for months at a time. For the most part, these are wildland firefighters, but sometimes they even have to enlist the help of teams from cities around the country. Wildland fires are not bound by the schedules of humans. Once they get going, they take on a life of their own. Firefighters are in it for the long haul, and many wildland firefighters go from fire to fire, spending the entire fire season far away from their families.

The other night my husband, Bob and I were watching a television program called FireStorm. The show focused on not just what happens during a wildfire, but also on the people who are affected by the fire, that most of us never think about…the firefighters. These are the people who leave their families at home and head out to fight a fire at a moments notice. Some of these people are gone for as much as nine months out of the year, going from fire to fire. These people include the smoke jumpers, the tanker  plane personnel, the hotshot units, and sometimes teams from cities in the area, as well as the Bureau of Land Management, and the Forest Service firefighting teams. These people talked about missing everything from school functions to weddings and childbirth. The fires wait for no man, and people depend on these men and women to drop everything and come quickly to try to save their homes.

plane personnel, the hotshot units, and sometimes teams from cities in the area, as well as the Bureau of Land Management, and the Forest Service firefighting teams. These people talked about missing everything from school functions to weddings and childbirth. The fires wait for no man, and people depend on these men and women to drop everything and come quickly to try to save their homes.

Smoke jumpers are especially isolated. They jump into a fire area and they are pretty much on their own for up to 3 weeks. The have to pack supplies, tents, and water with them. Part of it is dropped with the smoke jumpers and part of it with it’s own parachute. These firefighters are on their own now…in the middle of the monster. Obviously, they have ways out, but often it is by helicopter. They have to be alert at all times, and there is no time for fun and games. Smoke jumpers are essentially seal teams, when compared to the military. They go out on missions that no one else wants to attempt, and most often, they come back alive too. That is not always the case of course, because some of these teams have been overtaken and killed like the Prineville,  Oregon hotshot team killed on Storm King Mountain in Colorado, when the fire exploded and ran up the hill overtaking them. They paid the ultimate sacrifice for other people in an effort to save lives and homes.

Oregon hotshot team killed on Storm King Mountain in Colorado, when the fire exploded and ran up the hill overtaking them. They paid the ultimate sacrifice for other people in an effort to save lives and homes.

Firefighters who go out for months at a time fighting wildfires all over the country, are truly just as much deployed as their military counterparts, but we seldom think about the family side of their time fighting the fires. The spouses and children, and even parents and siblings, waiting and praying that their firefighter will make it home. It is a different kind of deployment, but it is a deployment nevertheless.

A sudden downpour near Terry, Montana on the evening of June 19, 1938 caused a flash flooding of the Custer Creek that would lead to a disaster before the night was over. Earlier in the day, a track walker was sent out the check the rail lines near Custer Creek which was located near the town of Terry, Montana. After his inspection, he reported to his superiors that the conditions were dry, and there were no problems with the tracks.

A sudden downpour near Terry, Montana on the evening of June 19, 1938 caused a flash flooding of the Custer Creek that would lead to a disaster before the night was over. Earlier in the day, a track walker was sent out the check the rail lines near Custer Creek which was located near the town of Terry, Montana. After his inspection, he reported to his superiors that the conditions were dry, and there were no problems with the tracks.

That was true at the time, but within a few hours, a sudden downpour overwhelmed Custer Creek. A small winding river, Custer Creek runs through 25 miles of the Great Plains before depositing into the Yellowstone River. Small streams like Custer Creek are prone to flash floods, because they don’t have  the capacity to handle any big influx of water, and their banks can quickly and easily be overtaken during heavy rains. As the water came rushing down stream, it washed out a bridge used by the trains. When the Olympian Special came through, it went crashing into the raging waters with no warning. Two sleeper cars were buried in the muddy waters. The night was pitch black seriously hampering rescue efforts. In all, 46 people lost their lives, and 60 others were seriously injured. The rear cars stayed above the water, but scores of passengers were seriously injured. They could not be evacuated until the following morning. I can’t even begin to imagine how awful that was.

the capacity to handle any big influx of water, and their banks can quickly and easily be overtaken during heavy rains. As the water came rushing down stream, it washed out a bridge used by the trains. When the Olympian Special came through, it went crashing into the raging waters with no warning. Two sleeper cars were buried in the muddy waters. The night was pitch black seriously hampering rescue efforts. In all, 46 people lost their lives, and 60 others were seriously injured. The rear cars stayed above the water, but scores of passengers were seriously injured. They could not be evacuated until the following morning. I can’t even begin to imagine how awful that was.

That was a tough week for Montana. Just a few days later, Black Eagle saw “torrents of water” that floated  furniture in the house of Sam Tadich, the sheriff had to help a rescue effort, the road to Giant Springs washed away and water was up to cows’ flanks around the Sun River. Havre’s worst flood came in June 22, 1938, when a cloudburst in the Bear Paw Mountains sent out a wall of water. Ten people were killed. Floating train cars were wedged under the viaduct, 10 miles of highway were underwater between Laredo and Box Elder, with a bridge washed out, the Havre Daily News reported. Rain is a good thing, but too much rain, coming too fast can devastate an area, especially one with a creek or river, in a very short time, and for Montana, it was a very rainy week, making it a very tough week.

furniture in the house of Sam Tadich, the sheriff had to help a rescue effort, the road to Giant Springs washed away and water was up to cows’ flanks around the Sun River. Havre’s worst flood came in June 22, 1938, when a cloudburst in the Bear Paw Mountains sent out a wall of water. Ten people were killed. Floating train cars were wedged under the viaduct, 10 miles of highway were underwater between Laredo and Box Elder, with a bridge washed out, the Havre Daily News reported. Rain is a good thing, but too much rain, coming too fast can devastate an area, especially one with a creek or river, in a very short time, and for Montana, it was a very rainy week, making it a very tough week.

During the Cold War, the threat of a nuclear attack was the biggest concern in world relationships. During the late 1960s, the United States learned that the Soviet Union had embarked upon a massive Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) buildup designed to catch up with the United States. The situation seemed to be heating up, because the Soviet Union seemed far more likely to use such weapons, so it looked like it was time to take action. In January 1967, President Lyndon Johnson announced that the Soviet Union had begun to construct a limited Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) defense system around Moscow. The development of an ABM system could allow one side to launch a first strike and then prevent the other from retaliating by shooting down incoming missiles. That was completely unacceptable.

During the Cold War, the threat of a nuclear attack was the biggest concern in world relationships. During the late 1960s, the United States learned that the Soviet Union had embarked upon a massive Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) buildup designed to catch up with the United States. The situation seemed to be heating up, because the Soviet Union seemed far more likely to use such weapons, so it looked like it was time to take action. In January 1967, President Lyndon Johnson announced that the Soviet Union had begun to construct a limited Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) defense system around Moscow. The development of an ABM system could allow one side to launch a first strike and then prevent the other from retaliating by shooting down incoming missiles. That was completely unacceptable.

President Johnson decided to call for strategic arms limitations talks…nicknamed SALT, and in 1967, he and Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin met at Glassboro State College in New Jersey. Johnson said they must gain “control of the ABM race,” and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara argued that the more each reacted to the other’s escalation, the more they had chosen “an insane road to follow.” Completely abolishing nuclear weapons would be impossible, but limiting the development of both offensive and defensive strategic systems could be done, and it might help stabilize relations between the  United States and the Soviet Union. The resulting SALT-I treaty was signed in 1972. The 1972 treaty limited a wide variety of nuclear weapons, but it did not address many of the other issues, so shortly after the SALT-I treaty was ratified, talks between the United States and the Soviet Union began anew. Those talks failed to achieve any new breakthroughs. By 1979, both the United States and the Soviet Union were eager to try again. For the United States, the thought that the Soviets were leaping ahead in the arms race was the primary motivator. For the Soviet Union, the increasingly close relationship between America and communist China was a cause for growing concern.

United States and the Soviet Union. The resulting SALT-I treaty was signed in 1972. The 1972 treaty limited a wide variety of nuclear weapons, but it did not address many of the other issues, so shortly after the SALT-I treaty was ratified, talks between the United States and the Soviet Union began anew. Those talks failed to achieve any new breakthroughs. By 1979, both the United States and the Soviet Union were eager to try again. For the United States, the thought that the Soviets were leaping ahead in the arms race was the primary motivator. For the Soviet Union, the increasingly close relationship between America and communist China was a cause for growing concern.

The SALT-II agreement was the result of those many nagging issues that were left over from the successful SALT-I treaty of 1972, but it had problems of its own. The treaty basically established numerical equality between the two nations in terms of nuclear weapons delivery systems. It also limited the number of MIRV missiles (missiles with multiple, independent nuclear warheads). In truth, the treaty did little or nothing to stop, or even substantially slow down, the arms race, and it met with unrelenting criticism in the United States. The treaty was thought to be a “sellout” to the Soviets. People believed that it would leave America virtually defenseless against a whole range of new weapons not mentioned in the agreement. Even supporters of arms control were less than enthusiastic about the treaty, since it did little to actually control arms. Nevertheless, during a summit meeting in Vienna, President Jimmy Carter and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev signed the  SALT-II agreement dealing with limitations and guidelines for nuclear weapons, on June 18, 1979. The treaty, would never formally go into effect, and it proved to be one of the most controversial agreements between the United States and the Soviet Union of the entire Cold War. Debate over SALT-II in the U.S. Congress continued for months. Then in December 1979, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. The Soviet attack effectively killed any chance of SALT-II being passed, and Carter ensured this by withdrawing the treaty from the Senate in January 1980. SALT-II thus remained signed, but was never ratified. During the 1980s, both nations agreed to respect the agreement until such time as new arms negotiations could take place.

SALT-II agreement dealing with limitations and guidelines for nuclear weapons, on June 18, 1979. The treaty, would never formally go into effect, and it proved to be one of the most controversial agreements between the United States and the Soviet Union of the entire Cold War. Debate over SALT-II in the U.S. Congress continued for months. Then in December 1979, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. The Soviet attack effectively killed any chance of SALT-II being passed, and Carter ensured this by withdrawing the treaty from the Senate in January 1980. SALT-II thus remained signed, but was never ratified. During the 1980s, both nations agreed to respect the agreement until such time as new arms negotiations could take place.

In the old west, few women went on to get a higher education, and even fewer became doctors. It was thought of as a man’s occupation, and the few women who dared to go into that field, were often looked at with distrust, and even disdain. People thought that women belonged in the home raising a family. Some didn’t even attempt to hide the dislike of women in medicine. Susan Anderson, MD was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1870. Her family moved to the mining camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado during her childhood. In 1893, Anderson left Cripple Creek to attend medical school at the University of Michigan. She graduated in 1897. During her time in medical school, Anderson contracted tuberculosis and soon returned to her family in Cripple Creek, where she set up her first practice.

In the old west, few women went on to get a higher education, and even fewer became doctors. It was thought of as a man’s occupation, and the few women who dared to go into that field, were often looked at with distrust, and even disdain. People thought that women belonged in the home raising a family. Some didn’t even attempt to hide the dislike of women in medicine. Susan Anderson, MD was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1870. Her family moved to the mining camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado during her childhood. In 1893, Anderson left Cripple Creek to attend medical school at the University of Michigan. She graduated in 1897. During her time in medical school, Anderson contracted tuberculosis and soon returned to her family in Cripple Creek, where she set up her first practice.

Anderson spent the next three years sympathetically tending to patients, but her father insisted that Cripple Creek, a lawless mining town at the time. He felt like it was no place for a woman, so Anderson moved to Denver. In Denver, she had a tough time securing patients. The people in Denver were reluctant to see a woman doctor. She then moved to Greeley, Colorado, where she worked as a nurse for six years. Somehow, people accepted a woman as a nurse, probably because they looked at it as just following the orders of the doctor, who was ultimately in charge.

Her tuberculosis got worse during this time, so she felt she needed a more cold and dry climate. She made the  decision to move to Fraser, Colorado in 1907. Fraser’s elevation of over 8,500 feet, definitely made the area cold and dry. Anderson was most concerned with getting her disease under control and didn’t open a practice. She didn’t even tell people that she was a doctor. Nevertheless, the word soon got out and the locals began to ask for her advice on various ailments, which soon led to her practicing her skills once again. Her reputation spread as she treated families, ranchers, loggers, railroad workers, and even an occasional horse or cow, which was not uncommon at the time. The vast majority of her patients required her to make house calls, though she never owned a horse or a car. Instead, she dressed in layers, wore high hip boots, and trekked through deep snows and freezing temperatures to reach her patients. Now that is dedication…especially for a woman trying to recover from Tuberculosis.

decision to move to Fraser, Colorado in 1907. Fraser’s elevation of over 8,500 feet, definitely made the area cold and dry. Anderson was most concerned with getting her disease under control and didn’t open a practice. She didn’t even tell people that she was a doctor. Nevertheless, the word soon got out and the locals began to ask for her advice on various ailments, which soon led to her practicing her skills once again. Her reputation spread as she treated families, ranchers, loggers, railroad workers, and even an occasional horse or cow, which was not uncommon at the time. The vast majority of her patients required her to make house calls, though she never owned a horse or a car. Instead, she dressed in layers, wore high hip boots, and trekked through deep snows and freezing temperatures to reach her patients. Now that is dedication…especially for a woman trying to recover from Tuberculosis.

During the many years that “Doc Susie,” which she familiarly became known as, practiced in the high mountains of Grand County, one of her busiest times was during the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919. Like people all over the world, Fraser locals also became sick in great numbers, and Dr Anderson found herself rushing from one deathbed to the next.

Another busy time for her was when the six-mile Moffat Tunnel was being built through the Rocky Mountains. Not long after construction began, she found herself treating numerous men who were injured during  construction. During this time, she was also asked to become the Grand County Coroner, a position that enabled her to confront the Tunnel Commission regarding working conditions and accidents. She hoped to make a difference. In the five years it took to complete the tunnel, there were about 19 who died and hundreds injured.

construction. During this time, she was also asked to become the Grand County Coroner, a position that enabled her to confront the Tunnel Commission regarding working conditions and accidents. She hoped to make a difference. In the five years it took to complete the tunnel, there were about 19 who died and hundreds injured.

Unlike physicians of today, Dr Anderson never became “rich” practicing her skills. Im not even sure you would say she made a middle class living, because she was often paid in firewood, food, services, and other items that could be bartered. Doc Susie continued to practice in Fraser until 1956. She died in Denver on April 16, 1960 and was buried in Cripple Creek, Colorado.

Despite having a domineering father, who was never pleased with anything he did, Edsel Ford, the son of the founder of Ford Motors is mainly remembered for the Edsel, a failed 1958-60 car model. In reality, he was one of the masterminds of the Allied victory in World War II. Against the wishes of his father, Edsel Ford telephones William Knudsen of the U.S. Office of Production Management on June 12, 1940, to confirm Ford Motor Company’s acceptance of Knudsen’s proposal to manufacture 9,000 Rolls-Royce-designed engines to be used in British and United States airplanes. In all, they would build, 9,000 B-24 Liberator bombers, 278,000 Jeeps, 93,000 military trucks, 12,000 armored cars, 3,000 tanks, and 27,000 tank engines, but it was not without a few stumbling blocks. Edsel and Charles Sorensen, Ford’s production chief, had apparently gotten the go-ahead from Henry Ford by June 12, when Edsel telephoned Knudsen to confirm that Ford would produce 9,000 Rolls-Royce Merlin airplane engines (6,000 for the RAF and 3,000 for the U.S. Army). However, as soon as the British press announced the deal, Henry Ford personally and publicly canceled it, telling a reporter: “We are not doing business with the British government or any other government.”

Despite having a domineering father, who was never pleased with anything he did, Edsel Ford, the son of the founder of Ford Motors is mainly remembered for the Edsel, a failed 1958-60 car model. In reality, he was one of the masterminds of the Allied victory in World War II. Against the wishes of his father, Edsel Ford telephones William Knudsen of the U.S. Office of Production Management on June 12, 1940, to confirm Ford Motor Company’s acceptance of Knudsen’s proposal to manufacture 9,000 Rolls-Royce-designed engines to be used in British and United States airplanes. In all, they would build, 9,000 B-24 Liberator bombers, 278,000 Jeeps, 93,000 military trucks, 12,000 armored cars, 3,000 tanks, and 27,000 tank engines, but it was not without a few stumbling blocks. Edsel and Charles Sorensen, Ford’s production chief, had apparently gotten the go-ahead from Henry Ford by June 12, when Edsel telephoned Knudsen to confirm that Ford would produce 9,000 Rolls-Royce Merlin airplane engines (6,000 for the RAF and 3,000 for the U.S. Army). However, as soon as the British press announced the deal, Henry Ford personally and publicly canceled it, telling a reporter: “We are not doing business with the British government or any other government.”

Unlike other automakers, Ford had already built a successful airplane in the 1920s called the Tri-Motor. That fact made them the logical choice when the war effort needed more planes. In two meetings in late May and early June 1940, Knudsen and Edsel Ford agreed that Ford would manufacture the new fleet of aircraft for the RAF on an expedited basis. The one significant obstacle was Edsel’s father Henry Ford, who still retained complete control over the company he founded, even though he had turned the figurehead control over to his son. Henry Ford was well known for his opposition to the possible U.S. entry into World War II, so it would be up to Edsel to convince him that it was necessary.

According to Douglas Brinkley’s biography of Ford, “Wheels for the World,” Henry Ford had in effect already accepted a contract from the German government. The Ford subsidiary Ford-Werke in Cologne was doing business with the Third Reich at the time, which Ford’s critics took as proof that he was concealing a pro-German bias behind his claims to be a man of peace. Nevertheless, as U.S. entry into the war became more of

a certainty, Ford reversed his position, and the company opened a large new government-sponsored facility at Willow Run, Michigan in May of 1941, for the purposes of manufacturing the B-24E Liberator bombers for the Allied war effort. Ford Motor plants also produced a great deal of other war materiel during World War II, including a variety of engines, trucks, jeeps, tanks and tank destroyers. The production needs met by Ford Motor Company during World War II were instrumental in the Allied victory in that war.

a certainty, Ford reversed his position, and the company opened a large new government-sponsored facility at Willow Run, Michigan in May of 1941, for the purposes of manufacturing the B-24E Liberator bombers for the Allied war effort. Ford Motor plants also produced a great deal of other war materiel during World War II, including a variety of engines, trucks, jeeps, tanks and tank destroyers. The production needs met by Ford Motor Company during World War II were instrumental in the Allied victory in that war.

During the Civil War, rail lines were crucial for moving supplies from one place to another. The different sides often tried to waylay the trains, derail the trains, or even destroy the rails. On June 10, 1864, a Confederate cavalry intercepted General Phillip Sheridan’s Union cavalry while they were trying to destroy a rail line near Trevilian Station, Virginia. The ensuing battle lasted two days before the Confederates were finally able to drive off the Union cavalry from the station, with minimal damage to a precious supply line.

During the Civil War, rail lines were crucial for moving supplies from one place to another. The different sides often tried to waylay the trains, derail the trains, or even destroy the rails. On June 10, 1864, a Confederate cavalry intercepted General Phillip Sheridan’s Union cavalry while they were trying to destroy a rail line near Trevilian Station, Virginia. The ensuing battle lasted two days before the Confederates were finally able to drive off the Union cavalry from the station, with minimal damage to a precious supply line.

After the Confederate victory at the Battle of Cold Harbor in June 1864, in which over 15,000 combined casualties fell during the nearly two-week fight, Union General Ulysses S. Grant dispatched his cavalry commander, General Phillip Sheridan to ride towards Charlottesville and cut the Virginia Central Railroad. The line was supplying Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Lee’s Army was engaged in a life-or-death struggle with Grant’s Army of the Potomac, in the areas of Richmond and Petersburg.

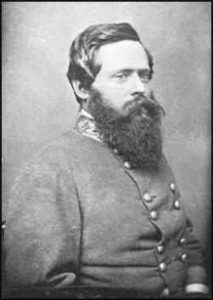

Sheridan turned north to skirt around Richmond and headed toward Charlottesville, which was 60 miles northwest of Richmond. Unfortunately, Sheridan’s move was far from secret, and General Wade Hampton, commander of the Confederate cavalry, set out to intercept the Union cavalry. On the morning of June 11, Union General George Custer’s men attacked Hampton’s supply train near Trevilian Station. Although they scored an initial success, Custer soon found himself almost completely surrounded by the Confederate Cavalry. Custer formed his men into a triangle and made several counterattacks before Sheridan came to his rescue in the late afternoon, taking 500 Southern prisoners in the process.

The struggle continued the next day. With his ammunition running low and his cavalry dangerously far from its supply line, Sheridan eventually withdrew his force and returned to the Army of the Potomac. The Union Cavalry tore up about five miles of rail line, but the damage was relatively light for the high number of casualties. Sheridan lost 735 men compared with nearly 1,000 for Hampton. But the Confederates had driven off the Union cavalry and had kept the damage to railroad to a minimum…not that it would make a difference in the outcome of the Civil War.

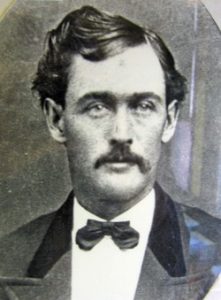

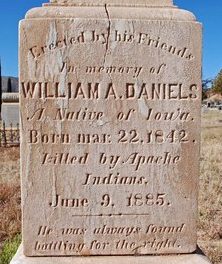

Many men helped to tame the wild west, but unfortunately things didn’t always go exactly as the lawmen planned. Billy Daniels was a pretty typical lawman, but like the thousands of courageous young men and women who helped tame the Wild West, whose names and stories have since been largely forgotten, Billy was not a well remembered lawman. For every Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp, who have been immortalized by the dramatic exaggerations of dime novelists and journalists, the West had dozens of men like Billy Daniels, who quietly did their duty with little fanfare, celebration, or thanks.

Many men helped to tame the wild west, but unfortunately things didn’t always go exactly as the lawmen planned. Billy Daniels was a pretty typical lawman, but like the thousands of courageous young men and women who helped tame the Wild West, whose names and stories have since been largely forgotten, Billy was not a well remembered lawman. For every Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp, who have been immortalized by the dramatic exaggerations of dime novelists and journalists, the West had dozens of men like Billy Daniels, who quietly did their duty with little fanfare, celebration, or thanks.

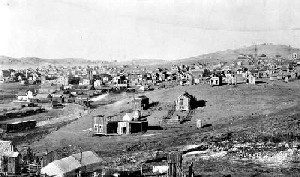

On December 8, 1883, five desperadoes led by Daniel “Big Dan” Dowd, rode into the booming mining town of Bisbee, Arizona. Dowd had heard that the $7,000 payroll of the Copper Queen Mine would be in the vault at the Bisbee General Store. He had planned to surprise the store owners, and make off with the payroll, but things didn’t go exactly as planned. When the outlaws barged into the store with their guns drawn, demanding the payroll, they discovered, to Dowd’s disappointment, that they were too early. The payroll hadn’t arrived yet. The outlaws quickly gathered up what money there was, somewhere between $900 to $3,000, and took valuable rings and watches from the customers who just happened to be in the store. After the robbery, for reasons that are unclear…but possibly, anger…the robbery turned into a slaughter. When the five desperadoes rode away, they left behind four dead or dying people, including Deputy Sheriff Tom Smith and a Bisbee woman named Anna Roberts.

The people of Arizona were stunned. The people had cooperated with the outlaws. There was no reason to kill  those people. The killings were a completely senseless show of brutality. The newspapers called it the “Bisbee Massacre.” The sheriff quickly organized citizen posses to track down the killers, placing Deputy Sheriff Billy Daniels at the head of one. Unfortunately, the posses soon ran out of clues and the trail grew cold. Most of the citizen members gave up, but not Daniels. He stubbornly continued the pursuit alone. Daniels eventually learned the identities of the five men from area ranchers and began to track them down one by one.

those people. The killings were a completely senseless show of brutality. The newspapers called it the “Bisbee Massacre.” The sheriff quickly organized citizen posses to track down the killers, placing Deputy Sheriff Billy Daniels at the head of one. Unfortunately, the posses soon ran out of clues and the trail grew cold. Most of the citizen members gave up, but not Daniels. He stubbornly continued the pursuit alone. Daniels eventually learned the identities of the five men from area ranchers and began to track them down one by one.

Daniels found one of the killers in Deming, New Mexico, and arrested him. He then learned from a Mexican informant that the gang leader, Big Dan Dowd, had fled south of the border to a hideout at Sabinal, Chihuahua. Daniels went under cover, disguising himself as an ore buyer. He tricked Dowd into a meeting and took him prisoner. A few weeks later, Daniels returned to Mexico and arrested another of the outlaws. Other law officers apprehended the remaining two members of the gang. A jury in Tombstone, Arizona, quickly convicted all five men. They were sentenced to be hanged simultaneously. As the noose was fitted around his neck on the five-man gallows, Big Dan reportedly muttered, “This is a regular killing machine.”

Daniels ran for sheriff the net year, but oddly lost. I would think that a hometown hero would be a shoo-in. After all he had done for the town, it would seem that being the sheriff was a thankless job. He found a new  position as an inspector of customs. The job required him to travel all around the vast and often isolated Arizona countryside, where various bands of hostile Apache Indians were a serious danger. Early on the morning of June 10, 1885, Daniels and two companions were riding up a narrow canyon trail in the Mule Mountains east of Bisbee. Daniels, who was in the lead, rode into an Apache ambush. The first bullets killed his horse, and the animal collapsed, pinning Daniels to the ground. Trapped, Daniels used his rifle to defend himself as best he could, but the Apache quickly overwhelmed him and cut his throat. A mere two years after Arizona Deputy Sheriff William Daniels apprehended three of the five outlaws responsible for the Bisbee Massacre, it was an Apache Indians ambush that would end his life. His two companions escaped with their lives and returned the next day with a posse. They found Daniels’ badly mutilated corpse but were unable to track the Apache Indians who murdered him. I guess they lacked Daniels’ under cover or investigative skills.

position as an inspector of customs. The job required him to travel all around the vast and often isolated Arizona countryside, where various bands of hostile Apache Indians were a serious danger. Early on the morning of June 10, 1885, Daniels and two companions were riding up a narrow canyon trail in the Mule Mountains east of Bisbee. Daniels, who was in the lead, rode into an Apache ambush. The first bullets killed his horse, and the animal collapsed, pinning Daniels to the ground. Trapped, Daniels used his rifle to defend himself as best he could, but the Apache quickly overwhelmed him and cut his throat. A mere two years after Arizona Deputy Sheriff William Daniels apprehended three of the five outlaws responsible for the Bisbee Massacre, it was an Apache Indians ambush that would end his life. His two companions escaped with their lives and returned the next day with a posse. They found Daniels’ badly mutilated corpse but were unable to track the Apache Indians who murdered him. I guess they lacked Daniels’ under cover or investigative skills.