History

You have probably heard of the famous “Shot Heard Round the World?” It is a phrase referring to several historical incidents, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, and particularly the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775. Tensions had been mounting because colonists were frustrated as Britain forced them to pay taxes. The big problem was that they did not give them any representation in the British Parliament. The colonists were fair minded people and this flew in the face of that fairness. They rallied behind the phrase, “no taxation without representation.” The first shots rang out on the morning of April 19, 1775 in Lexington, Massachusetts.

You have probably heard of the famous “Shot Heard Round the World?” It is a phrase referring to several historical incidents, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914, and particularly the beginning of the American Revolutionary War in 1775. Tensions had been mounting because colonists were frustrated as Britain forced them to pay taxes. The big problem was that they did not give them any representation in the British Parliament. The colonists were fair minded people and this flew in the face of that fairness. They rallied behind the phrase, “no taxation without representation.” The first shots rang out on the morning of April 19, 1775 in Lexington, Massachusetts.

At the Battle of Bunker Hill, colonial officer William Prescott ordered, “Do not fire until you see the whites of their eyes!” His troops had the courage and discipline to hold their fire until the enemy was near, an early sign that the rag-tag American army had a chance at defeating the well-trained, well-armed British troops. Congress chose George Washington as commander and chief of America’s armed forces. The Battle of Saratoga was the first great American victory of the war and is widely believed to have been the turning point that led America to triumph over Britain. The Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, and at last, Great Britain acknowledged America’s  independence. The treaty established a northern boundary with Canada and set the Mississippi River as the western boundary. In all 217,000 men took part in the war, and 4,435 lost their lives. Most people know all or at least most of this…or at least have read about it.

independence. The treaty established a northern boundary with Canada and set the Mississippi River as the western boundary. In all 217,000 men took part in the war, and 4,435 lost their lives. Most people know all or at least most of this…or at least have read about it.

However, you might not know that the Revolutionary War almost started early thanks to Sarah Tarrant, a nurse with a fiery temper who lived in Salem, Massachusetts in 1775, hurled insults at the retreating redcoats aimed his musket at her, and she dared him, “Fire, if you have the courage, but I doubt it.” No shots were fired, and the British, having found no weapons, left the town. Had he shot her, the war would have started earlier than it did.

The Swamp Ghost began its very short career on December 6, 1941, one day before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The Swamp Ghost started out as B-17 Flying Fortress, 41-2446 (which is not a tail number, and indicated that the plane was a new purchase) and under that number it was delivered to the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). Eleven days later, the bomber departed California for Hickam Field in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The plane and her crew were based at Wheeler Field in Wahiawa for a very short time, and flew patrol missions for the Navy until February 1942, when the Japanese Troops invaded Rabaul on New Britain and established a base. Of course, this was a threat to the rest of New Guinea and Australia. In response to the invasion, 41-2446 was ordered to Garbutt Field, Townsville, in Queensland, Australia. Swamp Ghost’s crew included Pilot Captain Frederick C. “Fred” Eaton, Co-Pilot Captain Henry M. “Hotfoot” Harlow, Navigator 1st Lieutenant George B. Munroe Jr, Bombardier Sergeant J.J. Trelia, Flight Engineer Technical Sergeant Clarence A. LeMieux, Radio Operator/Gunner Sergeant Howard A. Sorensen, Waist Gunner Sergeant William E. Schwartz, Waist Gunner Technical Sergeant Russell Crawford, and Tail Gunner Staff Sergeant John V. Hall. The only crew change would be Sergeant Richard Oliver, who replaced Bombardier Trelia after he became ill.

The Swamp Ghost began its very short career on December 6, 1941, one day before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The Swamp Ghost started out as B-17 Flying Fortress, 41-2446 (which is not a tail number, and indicated that the plane was a new purchase) and under that number it was delivered to the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF). Eleven days later, the bomber departed California for Hickam Field in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The plane and her crew were based at Wheeler Field in Wahiawa for a very short time, and flew patrol missions for the Navy until February 1942, when the Japanese Troops invaded Rabaul on New Britain and established a base. Of course, this was a threat to the rest of New Guinea and Australia. In response to the invasion, 41-2446 was ordered to Garbutt Field, Townsville, in Queensland, Australia. Swamp Ghost’s crew included Pilot Captain Frederick C. “Fred” Eaton, Co-Pilot Captain Henry M. “Hotfoot” Harlow, Navigator 1st Lieutenant George B. Munroe Jr, Bombardier Sergeant J.J. Trelia, Flight Engineer Technical Sergeant Clarence A. LeMieux, Radio Operator/Gunner Sergeant Howard A. Sorensen, Waist Gunner Sergeant William E. Schwartz, Waist Gunner Technical Sergeant Russell Crawford, and Tail Gunner Staff Sergeant John V. Hall. The only crew change would be Sergeant Richard Oliver, who replaced Bombardier Trelia after he became ill.

Because of the B-17’s long flying range, the Japanese control of Wake Island and Guam, and the Vichy government’s armistice with the Nazi government, 41-2446 island hopped nearly 5,700 detour miles to get to Townsville. They didn’t want to take a chance on running into enemy fighters, if they could help it. On February 22, 1942, nine B-17Es of the 19th Bombing Group were scheduled to take off for Rabaul. Unfortunately, this mission seemed doomed from the start, as nothing would go quite as planned. Out of the nine aircraft, four had to completely abort the mission due to mechanical problems. To further complicate matters, bad weather conditions made it difficult to see up in the air for those who were able to takeoff. Finally, poor visibility separated the five remaining in flight.

I would like to say that was all the problems they ran into, but there’s more. When 41-2446 was to drop its payload, the bomb bay malfunctioned. The crew had to go around for a second pass, where they managed a clear drop over their target. The Japanese were working hard to make this mission fail too. Japanese fire was intense and a flak round managed to punch a hole through the starboard wing of 41-2556. Fortunately for the crew, the wing didn’t detonate. While the crew hoped to make it to Fort Moresby, they were low on fuel. The dog-fight, had seen to that. They would have to land in New Guinea.

Captain Fred Eaton thought he was setting down the bomber in a wheat field, however, they actually landed wheels-up in the middle of Agaiambo swamp. The only good news in this horrific failure of a mission was that the crew was unscathed, except for one with minor cuts and scrapes. Now, they still had to get out of the swamp. It took two days of hacking their way through the razor-sharp kunai grass for the men to reach dry land. They ran into some locals who were chopping wood. The locals took them, horribly bitten by mosquitos and infected with malaria, to their village. After a night of rest, they traveled downriver in canoes, where they were handed over to an Australian magistrate, and eventually arrived at Port Moresby on April 1…thirty six days after their crash. After a week in the hospital, the men returned to combat, but their plane did not. After 41-2446’s crash, Captain Fred Eaton flew 60 more missions. Whenever these missions would take him over the crash site, he would circle it and tell his new crewmembers the story of what happened. I suppose it was therapeutic to re-live the amazing escape from the Agaiambo swamp. This was where the plane’s legend was born. After Eaton returned home, 41-2446 slipped from the public eye for nearly three decades.

Then, in 1972, some Australian soldiers happened upon the crash. After spotting the wreckage from a helicopter, they landed on the aircraft’s wing and found the plane semi-submerged, and strangely intact. The machine guns were in place, and even the coffee thermoses were intact. They nicknamed the plane, Swamp Ghost, and the name stuck. Thanks to warbird collector Charles Darby who included dozens of photographs in his book, Pacific Aircraft Wrecks, word spread in 1979 . Once the fad of recovering World War II aircraft really took off. Trekkers hiked into the site and began stripping the aircraft for keepsakes and sellable items. Despite the stripping, the aircraft structure itself remained remarkably intact, until it was removed from the swamp.

Alfred Hagen, a pilot and commercial builder from Pennsylvania, set his sights on Swamp Ghost and wanted to take it free it from the disintegration of the swamp. In November 2005, he obtained an export permit for the

B-17 for $100,000. For four weeks they labored over the aircraft, dismantling it in order to ship it out of the country. The controversy over its removal halted the cargo before it could be shipped to the United States. Eventually, it was cleared for import and by February 2010 it arrived at the Pacific Aviation Museum at Pearl Harbor for display.

B-17 for $100,000. For four weeks they labored over the aircraft, dismantling it in order to ship it out of the country. The controversy over its removal halted the cargo before it could be shipped to the United States. Eventually, it was cleared for import and by February 2010 it arrived at the Pacific Aviation Museum at Pearl Harbor for display.

Gunner was a stray male Kelpie, born in August 1941, who became notable for his reliability to accurately alert Allied Air Force personnel that Japanese aircraft were approaching Darwin during the Second World War. Gunner was six months old when he was found whimpering under a destroyed mess hut at Darwin Air Force base where he suffering a broken leg on February 19, 1942, following the first wave of Japanese attacks on Darwin.

Gunner was a stray male Kelpie, born in August 1941, who became notable for his reliability to accurately alert Allied Air Force personnel that Japanese aircraft were approaching Darwin during the Second World War. Gunner was six months old when he was found whimpering under a destroyed mess hut at Darwin Air Force base where he suffering a broken leg on February 19, 1942, following the first wave of Japanese attacks on Darwin.

Gunner was taken to a field hospital, but the doctor insisted he could not fix a “man” with a broken leg without knowing his name and serial number. The doctor repaired and plastered his leg after the air force personnel replied that his name was “Gunner” and his number was “0000”. Gunner entered the airforce on that day. It might have been unofficial, but only is the way he was “drafted.” Gunner’s Air Force career was very real. Leading Aircraftman Percy Westcott, one of the two airmen who found Gunner, took ownership of him and became his master and handler. Gunner was badly shaken after the bombing and quite skittish, but being only six months old he quickly responded to the attention of the men on base.

About a week later, Gunner first demonstrated his remarkable hearing skills. The men were working on the airfield, when Gunner became agitated. He started to whine and jump. A little while later, the sound of approaching airplane engines was heard by the airmen. Suddenly, a wave of Japanese raiders appeared in the skies above Darwin and began bombing and strafing the town. Somehow…Gunner knew. Two days later, Gunner became agitated again, and not long afterwards came another air attack. In the months that followed, the same pattern played out every time an attack occurred. Long before the sirens sounded, Gunner would become agitated and head for shelter. Because of Gunner’s amazing hearing he was able to warn air force personnel of approaching Japanese aircraft up to 20 minutes before they arrived and before they showed up on the radar. Gunner was never agitated when he heard Allied planes taking off or landing….just the enemy aircraft. Somehow Gunner could differentiate the sounds of Allied and enemy aircraft. He was so reliable that Wing Commander McFarlane gave approval for Westcott to sound a portable air raid siren whenever Gunner’s  whining or jumping alerted him. Before long, there were a number of stray dogs roaming the base. McFarlane gave the order that all dogs be shot, with the exception of Gunner. They couldn’t afford any distractions.

whining or jumping alerted him. Before long, there were a number of stray dogs roaming the base. McFarlane gave the order that all dogs be shot, with the exception of Gunner. They couldn’t afford any distractions.

Gunner became such a part of the air force that he slept under Westcott’s bunk, showered with the men in the shower block, sat with the men at the outdoor movie pictures, and went up with the pilots during practice take-off and landings. When Westcott was posted to Melbourne 18 months later, Gunner stayed in Darwin, looked after by the RAAF butcher. It is unknown what happened to Gunner after the war, but he was a most amazing dog.

Most of us who were around in the 1960s, know about the early space program, and especially the very first American to orbit the Earth…John Glenn. John Glenn’s historic flight put the United States on the map of the space race, so to speak. It all seems very commonplace in this day and age of space shuttles, and the International Space Station, but the reality was that this first American orbit could have ended tragically.

Most of us who were around in the 1960s, know about the early space program, and especially the very first American to orbit the Earth…John Glenn. John Glenn’s historic flight put the United States on the map of the space race, so to speak. It all seems very commonplace in this day and age of space shuttles, and the International Space Station, but the reality was that this first American orbit could have ended tragically.

While some change had happened concerning blacks and women, there was still much that had not changed. Women were not viewed as mathematically inclined, and black women even less so. That was before they knew about Katherine Johnson. Katherine Johnson was handpicked to be one of three black students to integrate West Virginia’s graduate schools. Born in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia in 1918, her intense curiosity and brilliance with numbers vaulted her ahead several grades in school. She graduated from high school at the age of 14, and the historically black West Virginia State University at 18, where she had made quick work of the school’s math curriculum. Katherine graduated with highest honors in 1937 and took a job teaching at a black public school in Virginia, but this was not to be her career.

In 1935, the NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, a precursor to NASA) hired five women to be their first computer pool at the Langley campus. “The women were meticulous and accurate…and they didn’t have to pay them very much,” NASA’s historian Bill Barry says, explaining the NACA’s decision. Six months later, after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II, NACA and Langley began recruiting African-American women with college degrees to work as human computers.

Johnson was hired by NACA in 1953. Johnson, along with Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson, became part of NASA’s team of human computers. These people were mathematicians who performed the necessary calculations to make space flight possible in a time when “machine computers” didn’t exist, or were very new. Johnson was perfect for this job. After working for Nasa a while, and really proving her worth, Johnson was still running into road blocks. When NASA engineer Paul Stafford was preparing a meeting about John Glenn’s upcoming mission. Johnson felt that she needed to be at that meeting to explain her numbers, but Stafford refused her the request to attend stating, “There’s no protocol for women attending.” Johnson instantly replied, “There’s no protocol for a man circling Earth either, sir.”

Johnson saw an opportunity when NASA installed huge IBM computers…that no one knew how to use. They tried to get the machines set up so that the human computers could be replaced by the far more accurate machines, but the set up proved too difficult, until Johnson taught herself to use the machines. She then taught the rest of the black women, human computers to run them too. In the end, they were the only ones who knew how to do it. It made them much more important to the space program. The men had to face the fact that the women, that they had all but discounted, were going to be the ones to save the space program.

The biggest highlight of Katherine Johnson’s career came at the point when John Glenn was getting ready to  make that historic first orbit around the Earth. Johnson’s main job in the lead-up and during the mission was to double-check and reverse engineer the newly-installed IBM 7090s trajectory calculations. There were very tense moments during the flight that forced the mission to end earlier than expected. John Glenn requested that Johnson specifically check and confirm trajectories and entry points that the IBM put out. Glenn didn’t completely trust the computer. So, he asked the head engineers to “get the girl to check the numbers…If she says the numbers are good…I’m ready to go.” Johnson couldn’t have been given a greater seal of approval than to have John Glenn say that she was the only one he trusted…after all, it was his life.

make that historic first orbit around the Earth. Johnson’s main job in the lead-up and during the mission was to double-check and reverse engineer the newly-installed IBM 7090s trajectory calculations. There were very tense moments during the flight that forced the mission to end earlier than expected. John Glenn requested that Johnson specifically check and confirm trajectories and entry points that the IBM put out. Glenn didn’t completely trust the computer. So, he asked the head engineers to “get the girl to check the numbers…If she says the numbers are good…I’m ready to go.” Johnson couldn’t have been given a greater seal of approval than to have John Glenn say that she was the only one he trusted…after all, it was his life.

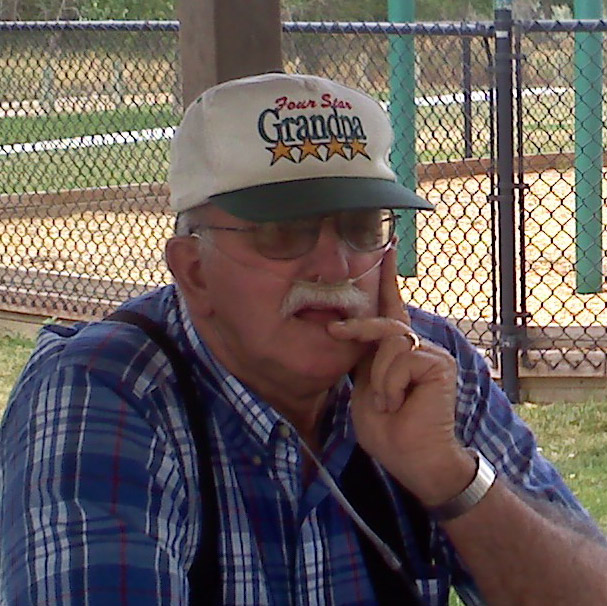

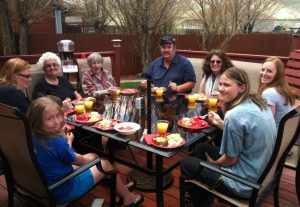

My Uncle Jack McDaniels was always a great guy…very pleasant and always ready with a joke of some other funny remark. All my life, I enjoyed being around him and my Aunt Bonnie. Uncle Jack went home to Heaven on July 14, 2012, and he has been greatly missed by his family ever since. As I was getting ready to write his birthday story, I wanted to capture his personality in a way that maybe many people did not know him, so I contacted his daughter-in-law, Deena for assistance. I like to think that my inquiry gave Deena and Michael a prime opportunity to remember his dad on his birthday, because what better way to remember a parent than happy memories discussed on their birthday.

My Uncle Jack McDaniels was always a great guy…very pleasant and always ready with a joke of some other funny remark. All my life, I enjoyed being around him and my Aunt Bonnie. Uncle Jack went home to Heaven on July 14, 2012, and he has been greatly missed by his family ever since. As I was getting ready to write his birthday story, I wanted to capture his personality in a way that maybe many people did not know him, so I contacted his daughter-in-law, Deena for assistance. I like to think that my inquiry gave Deena and Michael a prime opportunity to remember his dad on his birthday, because what better way to remember a parent than happy memories discussed on their birthday.

If you have ever been a part of a family on the larger side of size, you know that when they all get together, especially when there are little children in the mix, it is not a quiet event. Michael remembered a large family gathering that was quite loud, as you can imagine. Suddenly, everything went still…how that many people would all get quiet at the same time is shocking enough in and of itself. Nevertheless, for a few moments all was quiet before someone finally spoke. Uncle Jack said, in relief, “Thank goodness, I thought I had gone deaf!” I can absolutely see my Uncle Jack saying just that, with a twinkle in his eye, because that is how he was. He always saw the humor in life.

Uncle Jack and Aunt Bonnie’s son, Michael married his wife, Deena in 2006, so Deena got to know Uncle Jack for a little over six years. Deena told me about her first real interaction with Uncle Jack. Michael, having grown up with his dad’s influence, made the joke that he found Deena by the side of the road. So, when Uncle Jack met Deena for the first time, he said “So, you must be the hitchhiker!!!” The nickname stuck, and she is the hitchhiker to this day. It was all part of his teasing nature.

One thing I didn’t know, but wished I did, is that Uncle Jack loved local history. It is something he shared with Michael and Deena. Conversations between the three of them often centered around Casper and Natrona

County history. They all collect books on local history too. Uncle Jack would share his collection of books with us, and their love of history grew. Books on local history became popular gifts for birthdays and Christmas, and I’m sure they are extra special treasures, now that Uncle Jack is in Heaven, as are the wonderful conversations they had over the years. Today would have been Uncle Jack’s 81st birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Jack. We all love and miss you very much.

County history. They all collect books on local history too. Uncle Jack would share his collection of books with us, and their love of history grew. Books on local history became popular gifts for birthdays and Christmas, and I’m sure they are extra special treasures, now that Uncle Jack is in Heaven, as are the wonderful conversations they had over the years. Today would have been Uncle Jack’s 81st birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Jack. We all love and miss you very much.

I think most of us try to be nice people. We try to do nice things for our friends and loved ones, but what about random acts of kindness for people we don’t know. Most of us really put those things on the back burner, so to speak. It is probably a sad thing that there has to be a day set aside for random acts of kindness, but maybe we all need a reminder once in a while. There are always people who are less fortunate than we are…no matter how bad off we think we are. Most people think that random acts of kindness need to include money, but that isn’t so. The needs of those around us are not always monetary. Sometimes, people simply need a smile at the right moment, because they are feeling down. Other times, money is the need, of course. I think the key is to be aware, and to listen to your own spirit when it comes to hearing about the needs of those around you. If you feel led to do something for someone, act

I think most of us try to be nice people. We try to do nice things for our friends and loved ones, but what about random acts of kindness for people we don’t know. Most of us really put those things on the back burner, so to speak. It is probably a sad thing that there has to be a day set aside for random acts of kindness, but maybe we all need a reminder once in a while. There are always people who are less fortunate than we are…no matter how bad off we think we are. Most people think that random acts of kindness need to include money, but that isn’t so. The needs of those around us are not always monetary. Sometimes, people simply need a smile at the right moment, because they are feeling down. Other times, money is the need, of course. I think the key is to be aware, and to listen to your own spirit when it comes to hearing about the needs of those around you. If you feel led to do something for someone, act  upon that leading, using the appropriate amount of caution of course, because not everyone is nice.

upon that leading, using the appropriate amount of caution of course, because not everyone is nice.

Sometimes random acts of kindness should be anonymous too. I think that applies to most of the time. There is no need for recognition with random acts of kindness. In fact, that is the point of a random act of kindness, to remain anonymous…and even if they see you, they don’t have to know your name. All they have to know is that someone cared enough to do something nice for them. The thing that I always find to be true is that invariably, the person you choose to do something nice for, really needed to know that someone cared right then. We always think that we could not possibly know who needed our help, but I think that there are always telltale signs…even if it is just a feeling we have inside.

I suppose that sometimes, a random act of kindness can bless someone who, for all intents and purposes, doesn’t need any such act of kindness. Maybe there is nothing lacking in their life. Still, can a kindness shown ever be wasted? I don’t think so, because who could need a random act of kindness more than someone who thinks that they only have themselves to count on. We all know people who “don’t need any help” from anyone. To me, that is the saddest of all, because, as the saying goes, “no man is an island.” So today, if you have the chance to, show someone a random act of kindness, and maybe it could become a habit for every day.

This year marks the 82nd anniversary of the invention of nylon. For most of us, this invention was life-changing, whether we realize it or not. This invention was more than just the stockings or pantyhose that most of us think about, because nylon is in much more than that. It is used to make toothbrushes, umbrellas, hair brushes, fishing line, windbreakers, camping tents, winter gloves, kites, dog leashes, dog collars, guitar strings, guitar picks, children’s toys, racket strings, and medical implants, just to name a few of the nearly innumerable things made from nylon. People have Wallace Carothers and his team at DuPont to thank for it.

This year marks the 82nd anniversary of the invention of nylon. For most of us, this invention was life-changing, whether we realize it or not. This invention was more than just the stockings or pantyhose that most of us think about, because nylon is in much more than that. It is used to make toothbrushes, umbrellas, hair brushes, fishing line, windbreakers, camping tents, winter gloves, kites, dog leashes, dog collars, guitar strings, guitar picks, children’s toys, racket strings, and medical implants, just to name a few of the nearly innumerable things made from nylon. People have Wallace Carothers and his team at DuPont to thank for it.

The inspiration for nylon really came during the Great Depression. Women have always loved soft stockings, and at that time, silk was very expensive, and most women couldn’t afford them. So, by the mid-30s, several DuPont Chemicals scientists led by Wallace Carothers were secretly working on a prototype polymer known then as “fiber 6-6,” which is another name for nylon.

Though nylon was first synthesized in a DuPont Chemicals laboratory on February 28, 1935, it didn’t become available to the public until 1940. When it did, it was in the form of stockings, and women across the United States flocked to department stores to get their hands on a pair. While silk probably felt more luxurious, the cost of it made it impossible to get, so nylon stockings became a great alternative, and when I think about my Aunt Gladys silk stockings, and how as little girls, my sisters and I couldn’t resist the feel of them. All Aunt Gladys ever said was to be careful not to snag them. I think that most people would be seriously worried about them, simply because of the cost. I often wonder if she was secretly cringing over the whole situation.

Dupont thought about going into other lines of products, but with the money they were making on the women’s  stockings bringing in in $9 million for DuPont in 1940, or $150 million in today’s dollars. They were pretty much the exclusive line at that time. Nevertheless, despite its wildly successful first year, DuPont shifted nearly all of its nylon production from the consumer market to the military in 1941 as the United States entered World War II. Allied forces used the material for everything from parachutes to mosquito nets.

stockings bringing in in $9 million for DuPont in 1940, or $150 million in today’s dollars. They were pretty much the exclusive line at that time. Nevertheless, despite its wildly successful first year, DuPont shifted nearly all of its nylon production from the consumer market to the military in 1941 as the United States entered World War II. Allied forces used the material for everything from parachutes to mosquito nets.

By then, fashion trends had already spurred such high demand for the stockings that when consumers couldn’t get their hands on them, a sort of black market emerged. Some women even resorted to painting their legs in an effort to capture the look. When the war ended and production returned to pre-war levels, women rushed to department stores. They waited in lines that made early day Black Friday lines seem small by comparison, and sometimes even resulted in violent chaos. The phenomenon came to be known as the nylon riots. One of the most notable examples occurred in Pittsburgh in 1945, where 40,000 women lined up to try to snag a pair of nylons.

One of the first American battleships, the USS Maine weighed more than 6,000 tons and was built at a cost of more than $2 million. That was a lot of money back in 1884, when the USS Maine, several other new battleships, and other warships built by the United States Navy to modernize the fleet. The Maine was launched on November 18, 1889, and commissioned on September 17, 1895.

One of the first American battleships, the USS Maine weighed more than 6,000 tons and was built at a cost of more than $2 million. That was a lot of money back in 1884, when the USS Maine, several other new battleships, and other warships built by the United States Navy to modernize the fleet. The Maine was launched on November 18, 1889, and commissioned on September 17, 1895.

The ship was sent to Cuba on a friendly visit to protect the interests of Americans there after a rebellion against Spanish rule broke out in Havana in January, 1898. On February 15, 1898, while sitting in Cuba’s Havana harbor, the ship suddenly exploded, killing 260 of the fewer than 400 American crewmen onboard. The massive explosion of unknown origin, was the subject of an official U.S. Naval  Court of Inquiry, which ruled in March that the ship was blown up by a mine, without directly placing the blame on Spain. The majority of Congressmen and of the American public felt that there was little doubt that Spain was responsible and they called for a declaration of war.

Court of Inquiry, which ruled in March that the ship was blown up by a mine, without directly placing the blame on Spain. The majority of Congressmen and of the American public felt that there was little doubt that Spain was responsible and they called for a declaration of war.

Diplomatic failures to resolve the USS Maine explosion, in addition to the indignation the United States felt over Spain’s brutal suppression of the Cuban rebellion and continued losses to American investment, led to the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in April 1898. The destruction of USS Maine and the loss of life that accompanied it, played a large part in the beginning of that war. As we have seen in history both before and after this incident, waking the sleeping giant that is the United States is never a good idea. We may be slow to enter a war, but when we get into one, we go into it full bore. When this giant goes to war, we go to win.

It took the United States only three months to decisively defeat the Spanish forces on land and sea. In August an armistice halted the fighting. On December 12, 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed between the United States and Spain, officially ending the Spanish-American War and granting the United States its first overseas empire with the ceding of such former Spanish possessions as Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. In 1976, a team of American naval investigators concluded that the Maine explosion was likely caused by a fire that ignited its ammunition stocks, not by a Spanish mine or act of sabotage. I guess we will never know for sure.

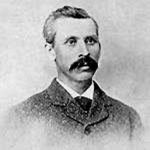

Shortly after President Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase from France, which made it an American territory, William Ashley, who was a Virginia native, made the decision to move to Missouri. Ashley was a young man, who was looking to make a name for himself. He entered into a partnership with Andrew Henry to manufacture gunpowder and lead. Opportunists, Ashley and Henry took advantage of the fact that these two commodities were in short supply in young America.

Shortly after President Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase from France, which made it an American territory, William Ashley, who was a Virginia native, made the decision to move to Missouri. Ashley was a young man, who was looking to make a name for himself. He entered into a partnership with Andrew Henry to manufacture gunpowder and lead. Opportunists, Ashley and Henry took advantage of the fact that these two commodities were in short supply in young America.

Ashley’s business prospered during the War of 1812, and he also joined the Missouri militia. He eventually achieved the rank of general. When Missouri became a state in 1822, Ashley used his military fame, and his business success to win election at lieutenant governor. Once elected, Ashley set about looking for opportunities to enrich both Missouri and his own pocketbook. Because he knew the area, he realized that Saint Louis was in a perfect place to exploit the fur trade on the upper Missouri River.

Ashley recruited his old business partner, Henry to join him in this new venture. Then, Ashley placed an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette and Public Advisor seeking 100 “enterprising young men” to engage in fur trading on the Upper Missouri. The advertisement was a big success. Scores of young men responded and came to Saint Louis. Among them were such future legendary mountain men as Jedediah Smith and Jim Bridger, as well as the famous river man Mike Fink. In time, these men and dozens of others would go on to uncover many of the geographic mysteries of the Far West, but for now they were looking to make a living trapping animals for their furs.

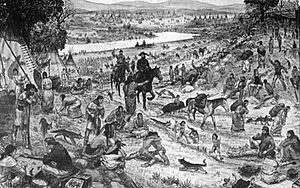

1822 found Ashley and a small band of his fur trappers building a trading post on the Yellowstone River in Montana in order to expand outward from the Missouri River. The Arikara Indians didn’t like this invasion, and they were deeply hostile to Ashley’s attempts to undercut their long-standing position as middlemen in the fur trade. The ensuing attacks eventually forced the men to abandon the Yellowstone post. Out of desperation, Ashley hit on a new strategy. Instead of building central permanent forts along the major rivers, he decided to send his trappers overland in small groups traveling by horseback. By avoiding the river arteries, the trappers could both escape detection by hostile Indians and develop new and untapped fur regions. Almost by accident, Ashley invented the famous “rendezvous” system that revolutionized the American fur trade. The necessary supplies were delivered and furs were delivered at meetings in a large meadow near the Henry’s Fork of Wyoming’s Green River in the early summer of 1825.

Ashley’s first fur trapper rendezvous was very successful. Ashley took home a tidy profit for his efforts. The fur  trappers not only had an opportunity to trade for supplies, but a chance to enjoy a few weeks of often drunken socializing. Ashley organized a second highly profitable rendezvous in 1826, and then decided to sell out. While he was no longer a part of it, his rendezvous system continued to be used by others. The system eventually became the foundation for the powerful Rocky Mountain Fur Company. With plenty of money in the bank, Ashley was able to return to his first love…politics. He was elected to Congress three times and once to the Senate, where he helped further the interests of the western land that had made him rich.

trappers not only had an opportunity to trade for supplies, but a chance to enjoy a few weeks of often drunken socializing. Ashley organized a second highly profitable rendezvous in 1826, and then decided to sell out. While he was no longer a part of it, his rendezvous system continued to be used by others. The system eventually became the foundation for the powerful Rocky Mountain Fur Company. With plenty of money in the bank, Ashley was able to return to his first love…politics. He was elected to Congress three times and once to the Senate, where he helped further the interests of the western land that had made him rich.

Most kids have, at one point or another, imagined that they were hunting for lost treasure. Some people, however, continue to be treasure hunters well into adulthood. Such was the case with two Michigan-based treasure hunters in 2011. The men were hunting for gold in Lake Michigan. Of course, that doesn’t mean they were looking for gold nuggets, like the gold rush days of old. They were looking for gold in the many shipwrecks of the Great Lakes.

Most kids have, at one point or another, imagined that they were hunting for lost treasure. Some people, however, continue to be treasure hunters well into adulthood. Such was the case with two Michigan-based treasure hunters in 2011. The men were hunting for gold in Lake Michigan. Of course, that doesn’t mean they were looking for gold nuggets, like the gold rush days of old. They were looking for gold in the many shipwrecks of the Great Lakes.

On this particular treasure hunting expedition, Kevin Dykstra and Frederick Monroe were searching for $2 million in gold that had, according to local legend, fallen from a ferry crossing Lake Michigan in the 1800s. While moving their sonar over the lake, it caught a mass below. Dykstra dove into the water to video the mass. “I didn’t go down there with the expectation of seeing a shipwreck–I can tell you that,” Dykstra told Live Science. Nevertheless, there beneath the cold waves of Lake Michigan was an aging shipwreck. Brown and gray zebra mussels, encrusted the wooden planks of the old ship. When Dykstra and Monroe reviewed the video, they realized that the ship might be the remnants of a 17th-century ship called the Griffin, or Le Griffon. French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle built the ship in 1679. It was lost in Lake Michigan the same year.

Some experts were not convinced that the men had indeed found the Griffin. The experts thought it might be the remnants of a tugboat that was scrapped after “steam engines became more economical to operate,” said Brendon Baillod, a Great Lakes historian, who has written scholarly papers on the Griffin. More evidence was needed to prove that this ship was the Griffin. State archaeologists reviewed the footage, and “They’ve been very diligent to say, ‘This is really interesting; these are some neat pictures,'” Dykstra said. “Can we call this the Griffin? Certainly not–not without a lot more information–but these are very compelling.”

La Salle apparently sailed the Griffin through the Great Lakes and crossed into Lake Michigan in an effort to reach the mouth of the Mississippi River, according to Baillod. Running out of money, he disembarked with the other expedition leaders, leaving the ship and its crew to pay off his debts with furs. “La Salle never saw the Griffin again. La Salle returned to the area in 1682, to try again to locate the Mississippi’s mouth. But members of the Potawatomi tribe brought pieces of the ship to the explorer, including some moldy beaver furs and a pair of sailor’s britches,” said Baillod, who translated La Salle’s journal from French to English.

The Native Americans told La Salle that the crew planned to sail toward the Straits of Mackinac in stormy weather. “The [American] Indians told the captain not to sail out, to wait the storm out, but he wouldn’t listen to them,” Baillod said. Of course, because of his haste to set sail, the captain lost control of the ship in the strong winds. The ship was blown away from shore, southward, toward some islands in the distance. “They lost the ship from sight,” Baillod said, “and that’s the last anybody has ever seen the Griffin.”

About 30 various adventurers have claimed to have found the Griffin, but have never really been able to prove their claim. “They’re looking for something else, they find an old ship and they’ve heard of the Griffin, so they pronounce it the Griffin,” Baillod said. According to Baillod, none of these adventurers were looking near the Beaver Island area, which was most likely the area the ship went down. But the latest finding, made popular again by Wreck Diving Magazine in its latest issue, holds a number of clues about the ship’s past. “There was no rudder on the boat,” Dykstra said. “That was kind of telling to us that the ship probably weathered a storm; otherwise, there would probably be a rudder on it.” They also found a part of the ship that they said could be a mussel-covered griffin, the mythical beast carved onto the ship’s bow.

Dykstra was so intrigued that he went back to have another look. He took a magnet with him to help determine the metal composition of the ship. Purely by accident, a nail attached itself to the magnet. The treasure hunters discovered it later, once they were above water. “When we had it looked at, they [the archaeologists] could tell that the nail was very old,” Dykstra said. “It was a hand-forged nail, which helps date it back to that time period, we feel.” Of course, this accident could have landed the men in hot water with the state of Michigan, which has rules stipulating that artifacts found on state land, including the land at the bottom of the Great Lakes, are state property. “The two men did not bring up the nail on purpose, and they plan to return it to the state,” said Dean Anderson, the state archaeologist for Michigan.

About 1,500 shipwrecks have been found on the bottom of Lake Michigan, Anderson said, and it’s unclear whether this one is the Griffin. “It’s very difficult to access a wreck based on photo and film footage,” Anderson said. If the state underwater archaeologist were to look at the wreck, he would look for artifacts that could be  dated, such as ceramics or glass. Baillod is “99 percent sure” that the wreck is not Le Griffon. The figurehead likely isn’t the remains of a griffin, but a “big encrustation of zebra mussels,” on burned wood. He noted that the wreck is near the western Michigan coast, not near Beaver Island, the area mentioned in La Salle’s journal. Nevertheless, Dykstra and Monroe said they’ll wait until they hear the final word. They’re not going back to the wreckage for a while, so they don’t make the site vulnerable to other treasure seekers. In the meantime, the duo plans to continue their hunt for the gold bullion. “It’s a mystery ship that got in our way,” Dykstra said, “and now, we’re going for the gold.”

dated, such as ceramics or glass. Baillod is “99 percent sure” that the wreck is not Le Griffon. The figurehead likely isn’t the remains of a griffin, but a “big encrustation of zebra mussels,” on burned wood. He noted that the wreck is near the western Michigan coast, not near Beaver Island, the area mentioned in La Salle’s journal. Nevertheless, Dykstra and Monroe said they’ll wait until they hear the final word. They’re not going back to the wreckage for a while, so they don’t make the site vulnerable to other treasure seekers. In the meantime, the duo plans to continue their hunt for the gold bullion. “It’s a mystery ship that got in our way,” Dykstra said, “and now, we’re going for the gold.”