History

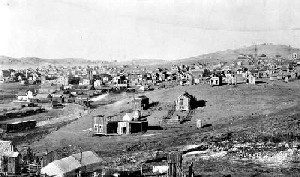

In the old west, few women went on to get a higher education, and even fewer became doctors. It was thought of as a man’s occupation, and the few women who dared to go into that field, were often looked at with distrust, and even disdain. People thought that women belonged in the home raising a family. Some didn’t even attempt to hide the dislike of women in medicine. Susan Anderson, MD was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1870. Her family moved to the mining camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado during her childhood. In 1893, Anderson left Cripple Creek to attend medical school at the University of Michigan. She graduated in 1897. During her time in medical school, Anderson contracted tuberculosis and soon returned to her family in Cripple Creek, where she set up her first practice.

In the old west, few women went on to get a higher education, and even fewer became doctors. It was thought of as a man’s occupation, and the few women who dared to go into that field, were often looked at with distrust, and even disdain. People thought that women belonged in the home raising a family. Some didn’t even attempt to hide the dislike of women in medicine. Susan Anderson, MD was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1870. Her family moved to the mining camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado during her childhood. In 1893, Anderson left Cripple Creek to attend medical school at the University of Michigan. She graduated in 1897. During her time in medical school, Anderson contracted tuberculosis and soon returned to her family in Cripple Creek, where she set up her first practice.

Anderson spent the next three years sympathetically tending to patients, but her father insisted that Cripple Creek, a lawless mining town at the time. He felt like it was no place for a woman, so Anderson moved to Denver. In Denver, she had a tough time securing patients. The people in Denver were reluctant to see a woman doctor. She then moved to Greeley, Colorado, where she worked as a nurse for six years. Somehow, people accepted a woman as a nurse, probably because they looked at it as just following the orders of the doctor, who was ultimately in charge.

Her tuberculosis got worse during this time, so she felt she needed a more cold and dry climate. She made the  decision to move to Fraser, Colorado in 1907. Fraser’s elevation of over 8,500 feet, definitely made the area cold and dry. Anderson was most concerned with getting her disease under control and didn’t open a practice. She didn’t even tell people that she was a doctor. Nevertheless, the word soon got out and the locals began to ask for her advice on various ailments, which soon led to her practicing her skills once again. Her reputation spread as she treated families, ranchers, loggers, railroad workers, and even an occasional horse or cow, which was not uncommon at the time. The vast majority of her patients required her to make house calls, though she never owned a horse or a car. Instead, she dressed in layers, wore high hip boots, and trekked through deep snows and freezing temperatures to reach her patients. Now that is dedication…especially for a woman trying to recover from Tuberculosis.

decision to move to Fraser, Colorado in 1907. Fraser’s elevation of over 8,500 feet, definitely made the area cold and dry. Anderson was most concerned with getting her disease under control and didn’t open a practice. She didn’t even tell people that she was a doctor. Nevertheless, the word soon got out and the locals began to ask for her advice on various ailments, which soon led to her practicing her skills once again. Her reputation spread as she treated families, ranchers, loggers, railroad workers, and even an occasional horse or cow, which was not uncommon at the time. The vast majority of her patients required her to make house calls, though she never owned a horse or a car. Instead, she dressed in layers, wore high hip boots, and trekked through deep snows and freezing temperatures to reach her patients. Now that is dedication…especially for a woman trying to recover from Tuberculosis.

During the many years that “Doc Susie,” which she familiarly became known as, practiced in the high mountains of Grand County, one of her busiest times was during the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919. Like people all over the world, Fraser locals also became sick in great numbers, and Dr Anderson found herself rushing from one deathbed to the next.

Another busy time for her was when the six-mile Moffat Tunnel was being built through the Rocky Mountains. Not long after construction began, she found herself treating numerous men who were injured during  construction. During this time, she was also asked to become the Grand County Coroner, a position that enabled her to confront the Tunnel Commission regarding working conditions and accidents. She hoped to make a difference. In the five years it took to complete the tunnel, there were about 19 who died and hundreds injured.

construction. During this time, she was also asked to become the Grand County Coroner, a position that enabled her to confront the Tunnel Commission regarding working conditions and accidents. She hoped to make a difference. In the five years it took to complete the tunnel, there were about 19 who died and hundreds injured.

Unlike physicians of today, Dr Anderson never became “rich” practicing her skills. Im not even sure you would say she made a middle class living, because she was often paid in firewood, food, services, and other items that could be bartered. Doc Susie continued to practice in Fraser until 1956. She died in Denver on April 16, 1960 and was buried in Cripple Creek, Colorado.

Despite having a domineering father, who was never pleased with anything he did, Edsel Ford, the son of the founder of Ford Motors is mainly remembered for the Edsel, a failed 1958-60 car model. In reality, he was one of the masterminds of the Allied victory in World War II. Against the wishes of his father, Edsel Ford telephones William Knudsen of the U.S. Office of Production Management on June 12, 1940, to confirm Ford Motor Company’s acceptance of Knudsen’s proposal to manufacture 9,000 Rolls-Royce-designed engines to be used in British and United States airplanes. In all, they would build, 9,000 B-24 Liberator bombers, 278,000 Jeeps, 93,000 military trucks, 12,000 armored cars, 3,000 tanks, and 27,000 tank engines, but it was not without a few stumbling blocks. Edsel and Charles Sorensen, Ford’s production chief, had apparently gotten the go-ahead from Henry Ford by June 12, when Edsel telephoned Knudsen to confirm that Ford would produce 9,000 Rolls-Royce Merlin airplane engines (6,000 for the RAF and 3,000 for the U.S. Army). However, as soon as the British press announced the deal, Henry Ford personally and publicly canceled it, telling a reporter: “We are not doing business with the British government or any other government.”

Despite having a domineering father, who was never pleased with anything he did, Edsel Ford, the son of the founder of Ford Motors is mainly remembered for the Edsel, a failed 1958-60 car model. In reality, he was one of the masterminds of the Allied victory in World War II. Against the wishes of his father, Edsel Ford telephones William Knudsen of the U.S. Office of Production Management on June 12, 1940, to confirm Ford Motor Company’s acceptance of Knudsen’s proposal to manufacture 9,000 Rolls-Royce-designed engines to be used in British and United States airplanes. In all, they would build, 9,000 B-24 Liberator bombers, 278,000 Jeeps, 93,000 military trucks, 12,000 armored cars, 3,000 tanks, and 27,000 tank engines, but it was not without a few stumbling blocks. Edsel and Charles Sorensen, Ford’s production chief, had apparently gotten the go-ahead from Henry Ford by June 12, when Edsel telephoned Knudsen to confirm that Ford would produce 9,000 Rolls-Royce Merlin airplane engines (6,000 for the RAF and 3,000 for the U.S. Army). However, as soon as the British press announced the deal, Henry Ford personally and publicly canceled it, telling a reporter: “We are not doing business with the British government or any other government.”

Unlike other automakers, Ford had already built a successful airplane in the 1920s called the Tri-Motor. That fact made them the logical choice when the war effort needed more planes. In two meetings in late May and early June 1940, Knudsen and Edsel Ford agreed that Ford would manufacture the new fleet of aircraft for the RAF on an expedited basis. The one significant obstacle was Edsel’s father Henry Ford, who still retained complete control over the company he founded, even though he had turned the figurehead control over to his son. Henry Ford was well known for his opposition to the possible U.S. entry into World War II, so it would be up to Edsel to convince him that it was necessary.

According to Douglas Brinkley’s biography of Ford, “Wheels for the World,” Henry Ford had in effect already accepted a contract from the German government. The Ford subsidiary Ford-Werke in Cologne was doing business with the Third Reich at the time, which Ford’s critics took as proof that he was concealing a pro-German bias behind his claims to be a man of peace. Nevertheless, as U.S. entry into the war became more of

a certainty, Ford reversed his position, and the company opened a large new government-sponsored facility at Willow Run, Michigan in May of 1941, for the purposes of manufacturing the B-24E Liberator bombers for the Allied war effort. Ford Motor plants also produced a great deal of other war materiel during World War II, including a variety of engines, trucks, jeeps, tanks and tank destroyers. The production needs met by Ford Motor Company during World War II were instrumental in the Allied victory in that war.

a certainty, Ford reversed his position, and the company opened a large new government-sponsored facility at Willow Run, Michigan in May of 1941, for the purposes of manufacturing the B-24E Liberator bombers for the Allied war effort. Ford Motor plants also produced a great deal of other war materiel during World War II, including a variety of engines, trucks, jeeps, tanks and tank destroyers. The production needs met by Ford Motor Company during World War II were instrumental in the Allied victory in that war.

During the Civil War, rail lines were crucial for moving supplies from one place to another. The different sides often tried to waylay the trains, derail the trains, or even destroy the rails. On June 10, 1864, a Confederate cavalry intercepted General Phillip Sheridan’s Union cavalry while they were trying to destroy a rail line near Trevilian Station, Virginia. The ensuing battle lasted two days before the Confederates were finally able to drive off the Union cavalry from the station, with minimal damage to a precious supply line.

During the Civil War, rail lines were crucial for moving supplies from one place to another. The different sides often tried to waylay the trains, derail the trains, or even destroy the rails. On June 10, 1864, a Confederate cavalry intercepted General Phillip Sheridan’s Union cavalry while they were trying to destroy a rail line near Trevilian Station, Virginia. The ensuing battle lasted two days before the Confederates were finally able to drive off the Union cavalry from the station, with minimal damage to a precious supply line.

After the Confederate victory at the Battle of Cold Harbor in June 1864, in which over 15,000 combined casualties fell during the nearly two-week fight, Union General Ulysses S. Grant dispatched his cavalry commander, General Phillip Sheridan to ride towards Charlottesville and cut the Virginia Central Railroad. The line was supplying Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Lee’s Army was engaged in a life-or-death struggle with Grant’s Army of the Potomac, in the areas of Richmond and Petersburg.

Sheridan turned north to skirt around Richmond and headed toward Charlottesville, which was 60 miles northwest of Richmond. Unfortunately, Sheridan’s move was far from secret, and General Wade Hampton, commander of the Confederate cavalry, set out to intercept the Union cavalry. On the morning of June 11, Union General George Custer’s men attacked Hampton’s supply train near Trevilian Station. Although they scored an initial success, Custer soon found himself almost completely surrounded by the Confederate Cavalry. Custer formed his men into a triangle and made several counterattacks before Sheridan came to his rescue in the late afternoon, taking 500 Southern prisoners in the process.

The struggle continued the next day. With his ammunition running low and his cavalry dangerously far from its supply line, Sheridan eventually withdrew his force and returned to the Army of the Potomac. The Union Cavalry tore up about five miles of rail line, but the damage was relatively light for the high number of casualties. Sheridan lost 735 men compared with nearly 1,000 for Hampton. But the Confederates had driven off the Union cavalry and had kept the damage to railroad to a minimum…not that it would make a difference in the outcome of the Civil War.

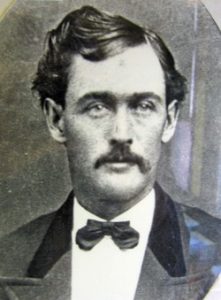

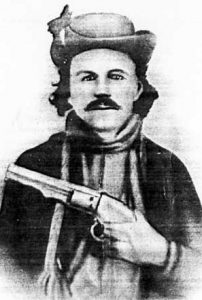

Many men helped to tame the wild west, but unfortunately things didn’t always go exactly as the lawmen planned. Billy Daniels was a pretty typical lawman, but like the thousands of courageous young men and women who helped tame the Wild West, whose names and stories have since been largely forgotten, Billy was not a well remembered lawman. For every Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp, who have been immortalized by the dramatic exaggerations of dime novelists and journalists, the West had dozens of men like Billy Daniels, who quietly did their duty with little fanfare, celebration, or thanks.

Many men helped to tame the wild west, but unfortunately things didn’t always go exactly as the lawmen planned. Billy Daniels was a pretty typical lawman, but like the thousands of courageous young men and women who helped tame the Wild West, whose names and stories have since been largely forgotten, Billy was not a well remembered lawman. For every Wild Bill Hickok or Wyatt Earp, who have been immortalized by the dramatic exaggerations of dime novelists and journalists, the West had dozens of men like Billy Daniels, who quietly did their duty with little fanfare, celebration, or thanks.

On December 8, 1883, five desperadoes led by Daniel “Big Dan” Dowd, rode into the booming mining town of Bisbee, Arizona. Dowd had heard that the $7,000 payroll of the Copper Queen Mine would be in the vault at the Bisbee General Store. He had planned to surprise the store owners, and make off with the payroll, but things didn’t go exactly as planned. When the outlaws barged into the store with their guns drawn, demanding the payroll, they discovered, to Dowd’s disappointment, that they were too early. The payroll hadn’t arrived yet. The outlaws quickly gathered up what money there was, somewhere between $900 to $3,000, and took valuable rings and watches from the customers who just happened to be in the store. After the robbery, for reasons that are unclear…but possibly, anger…the robbery turned into a slaughter. When the five desperadoes rode away, they left behind four dead or dying people, including Deputy Sheriff Tom Smith and a Bisbee woman named Anna Roberts.

The people of Arizona were stunned. The people had cooperated with the outlaws. There was no reason to kill  those people. The killings were a completely senseless show of brutality. The newspapers called it the “Bisbee Massacre.” The sheriff quickly organized citizen posses to track down the killers, placing Deputy Sheriff Billy Daniels at the head of one. Unfortunately, the posses soon ran out of clues and the trail grew cold. Most of the citizen members gave up, but not Daniels. He stubbornly continued the pursuit alone. Daniels eventually learned the identities of the five men from area ranchers and began to track them down one by one.

those people. The killings were a completely senseless show of brutality. The newspapers called it the “Bisbee Massacre.” The sheriff quickly organized citizen posses to track down the killers, placing Deputy Sheriff Billy Daniels at the head of one. Unfortunately, the posses soon ran out of clues and the trail grew cold. Most of the citizen members gave up, but not Daniels. He stubbornly continued the pursuit alone. Daniels eventually learned the identities of the five men from area ranchers and began to track them down one by one.

Daniels found one of the killers in Deming, New Mexico, and arrested him. He then learned from a Mexican informant that the gang leader, Big Dan Dowd, had fled south of the border to a hideout at Sabinal, Chihuahua. Daniels went under cover, disguising himself as an ore buyer. He tricked Dowd into a meeting and took him prisoner. A few weeks later, Daniels returned to Mexico and arrested another of the outlaws. Other law officers apprehended the remaining two members of the gang. A jury in Tombstone, Arizona, quickly convicted all five men. They were sentenced to be hanged simultaneously. As the noose was fitted around his neck on the five-man gallows, Big Dan reportedly muttered, “This is a regular killing machine.”

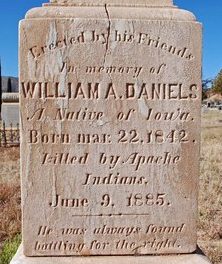

Daniels ran for sheriff the net year, but oddly lost. I would think that a hometown hero would be a shoo-in. After all he had done for the town, it would seem that being the sheriff was a thankless job. He found a new  position as an inspector of customs. The job required him to travel all around the vast and often isolated Arizona countryside, where various bands of hostile Apache Indians were a serious danger. Early on the morning of June 10, 1885, Daniels and two companions were riding up a narrow canyon trail in the Mule Mountains east of Bisbee. Daniels, who was in the lead, rode into an Apache ambush. The first bullets killed his horse, and the animal collapsed, pinning Daniels to the ground. Trapped, Daniels used his rifle to defend himself as best he could, but the Apache quickly overwhelmed him and cut his throat. A mere two years after Arizona Deputy Sheriff William Daniels apprehended three of the five outlaws responsible for the Bisbee Massacre, it was an Apache Indians ambush that would end his life. His two companions escaped with their lives and returned the next day with a posse. They found Daniels’ badly mutilated corpse but were unable to track the Apache Indians who murdered him. I guess they lacked Daniels’ under cover or investigative skills.

position as an inspector of customs. The job required him to travel all around the vast and often isolated Arizona countryside, where various bands of hostile Apache Indians were a serious danger. Early on the morning of June 10, 1885, Daniels and two companions were riding up a narrow canyon trail in the Mule Mountains east of Bisbee. Daniels, who was in the lead, rode into an Apache ambush. The first bullets killed his horse, and the animal collapsed, pinning Daniels to the ground. Trapped, Daniels used his rifle to defend himself as best he could, but the Apache quickly overwhelmed him and cut his throat. A mere two years after Arizona Deputy Sheriff William Daniels apprehended three of the five outlaws responsible for the Bisbee Massacre, it was an Apache Indians ambush that would end his life. His two companions escaped with their lives and returned the next day with a posse. They found Daniels’ badly mutilated corpse but were unable to track the Apache Indians who murdered him. I guess they lacked Daniels’ under cover or investigative skills.

When a mistake is made in the air, it usually results in a disaster. Air disasters often involve the pilot, a mechanic, or an old part. Of course, some of the worst disasters were caused when an air traffic controller sent two planes to the same place at the same altitude. The resulting mid-air collision killed everyone on board. Mistakes are never good, but in the air they are especially devastating.

When a mistake is made in the air, it usually results in a disaster. Air disasters often involve the pilot, a mechanic, or an old part. Of course, some of the worst disasters were caused when an air traffic controller sent two planes to the same place at the same altitude. The resulting mid-air collision killed everyone on board. Mistakes are never good, but in the air they are especially devastating.

War is no different, in fact mistakes in war can be really disastrous. Gunners shooting at the enemy planes are often so focused that when the enemy flies past their own squadron, they can end up shooting down their own squadron members with friendly fire.

The strange thing is that sometimes, a would be disaster ends up becoming one of the greatest miracles. Such was the case during World War II. The Americans planed a bombing run, and it was going to be a big bombing run. The orders had been issued. The problem…one squadron accidentally showed up thousands of feet lower down than the other one. In many cases, this would not have bee such a big problem, but both squadrons ended up a the drop site at the same time. The scheduled bombing began, and no one would really realize what was about to happen until it was too late.

Neither of the squadrons saw each other, until the bombs had been dropped. Miraculously, none of the lower planes were hit by the higher planes. It was a miracle of epic proportions. In addition, the Germans thought  that the Allies had come up with an ingenious bombing strategy to bomb an area twice as much. After that bombing event, the Germans were scared that the Allies had this level of skill. It seemed completely impossible that they could plan a bomb run in which the lower planes flew in sync enough to allow the upper planes to drop their bombs in between the lower planes, while the lower planes were also dropping their bombs. It was impossible, and yet it happened. The impossible was achieved without one bit of planning. There is simply no other word for it. It was a miracle. God took a potential disaster and turned it into one of the greatest feats of warfare.

that the Allies had come up with an ingenious bombing strategy to bomb an area twice as much. After that bombing event, the Germans were scared that the Allies had this level of skill. It seemed completely impossible that they could plan a bomb run in which the lower planes flew in sync enough to allow the upper planes to drop their bombs in between the lower planes, while the lower planes were also dropping their bombs. It was impossible, and yet it happened. The impossible was achieved without one bit of planning. There is simply no other word for it. It was a miracle. God took a potential disaster and turned it into one of the greatest feats of warfare.

I grew up in a time when western shows were all the rage on television. One show that my family always watched was Daniel Boone. Most people know Daniel Boone from their history classes, as an American frontiersman. Most of his fame stemmed from his exploits during the exploration and settlement of Kentucky. Boone arrived in Kentucky in 1767, about 25 years before it became a state on June 1, 1792. He spent the next 30 years exploring and settling the lands of Kentucky, including carving out the Wilderness Road and building the settlement station of Boonesboro. Without Boone the history of Kentucky would have been much different.

I grew up in a time when western shows were all the rage on television. One show that my family always watched was Daniel Boone. Most people know Daniel Boone from their history classes, as an American frontiersman. Most of his fame stemmed from his exploits during the exploration and settlement of Kentucky. Boone arrived in Kentucky in 1767, about 25 years before it became a state on June 1, 1792. He spent the next 30 years exploring and settling the lands of Kentucky, including carving out the Wilderness Road and building the settlement station of Boonesboro. Without Boone the history of Kentucky would have been much different.

Boone was born near Reading, in Berks County, Pennsylvania, the son of hard-working but adventurous Quaker parents. He learned some blacksmithing, but had very little formal education. Daniel appears to have been a scrappy lad who loved hunting, the wilderness, and independence. When his parents left Pennsylvania in 1750 bound for the Yadkin valley of northwest North Carolina, Daniel went along willingly, because the move fit right in with his spirit of adventure.

Upon arriving in North Carolina, the cutting edge of the frontier, he was able to indulge his hunting prowess and love of the wilderness. In the years that followed, he served as a wagoner with General Edward Braddock’s ill-fated expedition to Fort Duquesne in 1755. Boone then married a neighbor’s daughter, Rebecca Bryan, in 1756, and in 1758 is believed to have been a wagoner with General John Forbes who was hacking out the road to Fort Duquesne, which he rebuilt as Fort Pitt…now Pittsburgh. Back in North Carolina, Daniel purchased land from his father but never seriously engaged in farming. He loved to roam far too much to settle down and farm the land in one place. In 1763 he and his brother Squire journeyed to Florida, but for unknown reasons they did not stay. I guess Kentucky would always be his first love.

Boone was first in eastern Kentucky in 1767, but his expedition of 1769-1771 is more widely known. With a small party Boone advanced along the Warrior’s Path into a beautiful garden-like region. When the time came for the party to return he remained behind in the wilderness until March 1771. On the way home, he and his brother were robbed by Indians of their deer skins and pelts, but the two remained exuberant over the land known as “Kentuck.”

So much did Daniel love that “dark and bloody ground” that he tried to return in 1773, taking forty settlers with him, but the Indians drove them back. The next year he went again into the region carrying a warning of Indian troubles to Governor John Murray Dunmore’s surveyors. As Judge Richard Henderson was concluding the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. in March 1775, by which much of Kentucky was sold to his Transylvania Company, Boone was hacking out the Wilderness Road. As soon as he reached his destination, he began building Boonesboro, one of several stations, or forts under construction at that time. For the next four years…through 1778…Boone was a captain in the militia, and was busy defending the settlements. His leadership  helped save the three remaining Kentucky stations, Boonesboro, Logan’s (St. Asaph’s), and Harrodsburg. These were years of many ambushes; such as Blue Licks in 1778; captures, including Boone, himself, who was was captured but escaped from the Shawnees; rescues, and desperate defenses.

helped save the three remaining Kentucky stations, Boonesboro, Logan’s (St. Asaph’s), and Harrodsburg. These were years of many ambushes; such as Blue Licks in 1778; captures, including Boone, himself, who was was captured but escaped from the Shawnees; rescues, and desperate defenses.

I knew and have learned much about Daniel Boone over the years, but for me the most interesting thing I have learned is that Daniel Boone is my 5th Cousin 8 times removed, on the Pattan side of my mother, Collene Spencer’s family. It is a small, small world. Today is Daniel Boone Day. It is a day to remember all this great man did for our country.

People love to fight…be it in a war, debate, argument, or feud. It’s not so much a matter of loving to fight really, as it is an inability to get along, due to very differing opinions and ideas. One of the best known of all the feuds in Texas was the Lee-Peacock Feud. This feud took place in northeast Texas following the Civil War. It was a continuation of the war that would last for four bloody years after the rest of the nation had laid down their arms.The feud was fought in the Corners region of northeast Texas, where Grayson, Fannin, Hunt, and Collin Counties converged in an area known as the “Wildcat Thicket.” This thicket, covering many square miles, was so dense with trees, tall grass, brier brush, and thorn vines, that few people had even ventured into it until the Civil War, when it became a haven for army deserters and outlaws. It was in the northern part of this thicket that Daniel W Lee had built his home and raised his son, Bob Lee, who would become one of the leaders in the feud that was to come.

People love to fight…be it in a war, debate, argument, or feud. It’s not so much a matter of loving to fight really, as it is an inability to get along, due to very differing opinions and ideas. One of the best known of all the feuds in Texas was the Lee-Peacock Feud. This feud took place in northeast Texas following the Civil War. It was a continuation of the war that would last for four bloody years after the rest of the nation had laid down their arms.The feud was fought in the Corners region of northeast Texas, where Grayson, Fannin, Hunt, and Collin Counties converged in an area known as the “Wildcat Thicket.” This thicket, covering many square miles, was so dense with trees, tall grass, brier brush, and thorn vines, that few people had even ventured into it until the Civil War, when it became a haven for army deserters and outlaws. It was in the northern part of this thicket that Daniel W Lee had built his home and raised his son, Bob Lee, who would become one of the leaders in the feud that was to come.

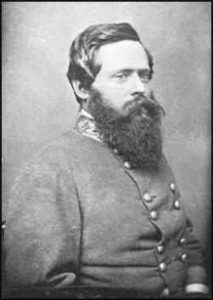

When the Civil War broke out, Bob Lee, by that time married with three children, quickly joined the Confederate Army, serving with the Ninth Texas Cavalry. Other young men in the area, including the Maddox brothers…John, William, and Francis; their cousin Jim Maddox, and several of the Boren boys, also joined the Ninth. Towards the end of the war, Bob heard that the Union League, an organization that worked for the protection of the blacks and Union sympathizers, had set up its North Texas headquarters at Pilot Grove, just about seven miles away from the Lee family homes.

The head of the Union League was a man named Lewis Peacock, who had arrived in Texas in 1856 and lived just south of Pilot Grove. Federal Troops were sent to Texas to aid in reconstruction efforts. By the time the Confederate soldiers returned to their homes in northeast Texas, the area was already in heavy conflict. Whether they owned slaves or not, most area residents resented the intrusion of Reconstruction ideals and new laws. When Bob Lee returned home, he was seen as a natural leader for the “Civil War” that was still being fought in northeast Texas.

To Peacock, Lee was seen as a threat to his cause and to reconstruction itself. To remove this threat, the Union League conceived of the idea to extort money from Lee. Peacock and his cohorts arrived at Lee’s house one night and “arrested” him, allegedly for crimes that he had committed during the Civil War. Lee would later say that he recognized the men as Lewis Peacock, James Maddox, Bill Smith, Sam Bier, Hardy Dial, Doc Wilson, and Israel Boren. Stating to Lee that he was to be taken into Sherman, they instead stopped in Choctaw Creek bottoms, where they took Lee’s watch, a $20 gold coin, and forced him to sign a promissory note for $2,000. The Lee’s refused to pay the note, bringing suit in Bonham, Texas and winning the case. This was the start of an all-out war, known as the Lee-Peacock Feud.

Both men gathered their friends and sympathizers and from 1867 through June 1869, a second “Civil War” raged in northeast Texas. An estimated 50 men losing their lives. By the summer of 1868, it had become so heated that the Union League requested help from the Federal Government, to which General JJ Reynolds posted a reward of $1,000 for the capture of Bob Lee. In late February, 1867, Lee was in a store in Pilot Grove when he ran across Jim Maddox, one of the men who had kidnapped him. Confronting Maddox, Lee offered Maddox a gun so they could fight. When Lee turned around to walk away, a bullet grazed his ear and head and he fell to the ground unconscious. Lee was taken to Dr William H Pierce, who treated him in his home. A report went to Austin to the Headquarters of the Fifth Military District under command of General John J. Reynolds, and the following entry was made in his ledger: “Murder and Assaults with Intent to Kill”, listed as criminals were James Maddox and John Vaught, listed as injured was Robert Lee. The charge: “Assault with intent to murder.” The result: “Set aside by the Military”. A few days later, on February 24, 1867, while Lee was still, convalescing in Pierce’s home, the doctor was shot to death by Hugh Hudson, a known Peacock man. Lee swore to avenge Pierce’s death and as word spread to both sides of the conflict, neighbors in the thickets of Four Corners began to arm themselves.

Hugh Hudson, the doctor’s killer was later shot at Saltillo, a teamster’s stop on the road to Jefferson. The feud had begun in full force. In 1868, Lige Clark, Billy Dixon, Dow Nance, Dan Sanders, Elijah Clark, and John Baldock were killed and many others wounded. Even Peacock suffered a wound at the hands of Lee’s followers. On August 27, 1868, General J. J. Reynolds issued the $1,000 reward for Bob Lee, dead or alive, an act that attracted bounty hunters from all over the country to the “Four Corners.” Three of these men, union sympathizers from Kansas, converged on the area in the early spring of 1869 to try to capture Lee. Instead, all three were found dead on the road. Bob Lee, in the meantime, had set up a hideout in the “Wildcat Thicket.”

General JJ Reynolds responded by dispatching the Fourth United States Cavalry to search for Lee and attempt to settle the trouble in the area. As they began a search from house to house for Lee, in which several gun battles ensued and several men were killed. In the end, one of Bob Lee’s “supporters,” a man named Henry Boren, betrayed him to the cavalry who shot down Lee on May 24, 1869. Later, Boren was shot down by his  own nephew, Bill Boren, who was a Lee supporter and felt that a “traitor” had to be put to death. After he killed his uncle, Bill Boren left the area and began to ride with John Wesley Hardin.

own nephew, Bill Boren, who was a Lee supporter and felt that a “traitor” had to be put to death. After he killed his uncle, Bill Boren left the area and began to ride with John Wesley Hardin.

As the Texas authorities had hoped, the killing of Lee began to dissolve the heated dispute, as many men scattered to other parts of the state. Though they were fewer in number, the “war” continued for two years, as more men were killed in both the four-corners region and other parts of the state. It wouldn’t be until Lewis Peacock was shot on June 13, 1871, that the feud finally ended.

Most people have heard of Crazy Horse, the Lakota Sioux Indian who has been memorialized in the Black Hills. Most of us know that Crazy Horse was a great warrior, but I did not know much about his upbringing. Crazy Horse was born on the Republican River about 1845. Crazy Horse was an uncommonly handsome man, and a man of refinement and grace. He was as modest and courteous as Chief Joseph, but unlike Chief Joseph, Crazy Horse was a born warrior, but a gentle warrior, a true brave, who stood for the highest ideal of the Lakota Sioux people. Of course, you would never hear these things from his enemies, but history should probably judge him more by the accounts of those who knew him…his own people.

Most people have heard of Crazy Horse, the Lakota Sioux Indian who has been memorialized in the Black Hills. Most of us know that Crazy Horse was a great warrior, but I did not know much about his upbringing. Crazy Horse was born on the Republican River about 1845. Crazy Horse was an uncommonly handsome man, and a man of refinement and grace. He was as modest and courteous as Chief Joseph, but unlike Chief Joseph, Crazy Horse was a born warrior, but a gentle warrior, a true brave, who stood for the highest ideal of the Lakota Sioux people. Of course, you would never hear these things from his enemies, but history should probably judge him more by the accounts of those who knew him…his own people.

No matter what Crazy Horse the man was or was thought to be, Crazy Horse, the boy showed great bravery a number of times. In those days, the Sioux prided themselves on the training and development of their sons and daughters, and not a step in that development was overlooked as an excuse to bring the child before the public by giving a feast in its honor. At such times the parents often gave so generously to the needy that they almost impoverished themselves, thus setting an example to the child of self-denial for the general good. His first step alone, the first word spoken, first game killed, the attainment of manhood or womanhood, each was the occasion of a feast and dance in his honor, at which the poor always benefited to the full extent of the parents’ ability. He was carefully brought up according to the tribal customs. I suppose it would have put him in the Indian version of today’s high society.

He was about five years old when the tribe was snowed in one severe winter. They were very short of food, but his father tirelessly hunted for food. The buffalo, their main dependence, were not to be found, but he was out in the storm and cold every day and finally brought in two antelopes. Young Crazy Horse got on his pet pony and rode through the camp, telling the old folks to come to his mother’s teepee for meat. Neither his father nor mother had authorized him to do this, and before they knew it, old men and women were lined up before the teepee home, to receive the meat, in answer to his invitation. As a result, the mother had to distribute nearly all of it, keeping only enough for two meals. On the following day he asked for food. His mother told him that the old folks had taken it all, and added: “Remember, my son, they went home singing praises in your name, not my name or your father’s. You must be brave. You must live up to your reputation.” And so he did.

When he was about twelve he went to look for the ponies with his little brother, whom he loved much, and took a great deal of pains to teach what he had already learned. They came to some wild cherry trees full of ripe fruit. Suddenly, the brothers were startled by the growl and sudden rush of a bear. Young Crazy Horse pushed his brother up into the nearest tree and then jumped upon the back of one of the horses, which was frightened and ran some distance before he could control him. As soon as he could, he turned him about and came back, yelling and swinging his lariat over his head. The bear at first showed fight but finally turned and ran. The old man who told me this story added that young as he was, he had some power, so that even a grizzly did not care to tackle him. I believe it is a fact that a grizzly will dare anything except a bell or a lasso line, so he accidentally hit upon the very thing which would drive him off.

At this period of his life, as was customary with the best young men, he spent much time in prayer and solitude. Just what happened in these days of his fasting in the wilderness and upon the crown of bald buttes, no one will ever know. These things may only be known when one has lived through the battles of life to an honored old age. He was much sought after by his youthful associates, but was noticeably reserved and modest. Yet, in the moment of danger he at once rose above them all…a natural leader! Crazy Horse was a typical Sioux brave, and from the point of view of the white man, an ideal hero.

At the age of sixteen he joined a war party against the Gros Ventres. He was well in the front of the charge,  and at once established his bravery by following closely one of the foremost Sioux warriors, by the name of Hump, drawing the enemy’s fire and circling around their advance guard. Suddenly Hump’s horse was shot from under him, and there was a rush of warriors to kill or capture him while he was down. Amidst a shower of arrows Crazy Horse jumped from his pony, helped his friend into his own saddle, sprang up behind him, and carried him off to safety, although they were hotly pursued by the enemy. Thus, in his first battle he associated himself with the wizard of Indian warfare, and Hump, who was then at the height of his own career. Hump pronounced Crazy Horse the coming warrior of the Teton Sioux. He was killed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1877, so that he lived barely thirty-three years.

and at once established his bravery by following closely one of the foremost Sioux warriors, by the name of Hump, drawing the enemy’s fire and circling around their advance guard. Suddenly Hump’s horse was shot from under him, and there was a rush of warriors to kill or capture him while he was down. Amidst a shower of arrows Crazy Horse jumped from his pony, helped his friend into his own saddle, sprang up behind him, and carried him off to safety, although they were hotly pursued by the enemy. Thus, in his first battle he associated himself with the wizard of Indian warfare, and Hump, who was then at the height of his own career. Hump pronounced Crazy Horse the coming warrior of the Teton Sioux. He was killed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska, in 1877, so that he lived barely thirty-three years.

On June 1, 2009, Air France Flight number 447 went down in the Atlantic Ocean. The flight took off from Rio de Janeiro on May 31, 2009.It was on it’s way to Paris, but nose-dived into the ocean long before reaching it’s destination. All 228 people on board were killed. A combination of bad weather, pilot error, and the captain’s extra-marital affair contributed to the deadliest crash in Air France history. Junior co-pilot Pierre-Cedric Bonin, 32, was piloting the Airbus A330 when it hit a thunderstorm over the sea. Bonin and fellow co-pilot David Robert, 37, pitched their craft sharply up instead of down, a fatal error that caused the plane to stall and and then pitch down, leading to the nose-dive into the ocean. Complicating the situation, Marc Dubois, the 58-year-old captain, had left the cockpit to take a nap, because he had been up all night with his mistress, and by the time he returned, it was too late to avoid catastrophe. Dubois had more than 11,000 flight hours compared to Bonin, who had logged a little less than 3,000.

On June 1, 2009, Air France Flight number 447 went down in the Atlantic Ocean. The flight took off from Rio de Janeiro on May 31, 2009.It was on it’s way to Paris, but nose-dived into the ocean long before reaching it’s destination. All 228 people on board were killed. A combination of bad weather, pilot error, and the captain’s extra-marital affair contributed to the deadliest crash in Air France history. Junior co-pilot Pierre-Cedric Bonin, 32, was piloting the Airbus A330 when it hit a thunderstorm over the sea. Bonin and fellow co-pilot David Robert, 37, pitched their craft sharply up instead of down, a fatal error that caused the plane to stall and and then pitch down, leading to the nose-dive into the ocean. Complicating the situation, Marc Dubois, the 58-year-old captain, had left the cockpit to take a nap, because he had been up all night with his mistress, and by the time he returned, it was too late to avoid catastrophe. Dubois had more than 11,000 flight hours compared to Bonin, who had logged a little less than 3,000.

Dubois and the rest of his crew had arrived in Rio three days before Flight 447’s departure. The probe’s lead  French investigator believes that the pilot, Dubois could have properly navigated the storm, but he was napping. “If the captain had stayed in position . . . it would have delayed his sleep by no more than 15 minutes, and because of his experience, maybe the story would have ended differently,” chief French investigator Alain Bouillard said. A search was quickly organized, but the plane sank to the ocean floor and wasn’t found for nearly two years. An oil slick thought to have been left by the downed Air France flight was spotted on June 3, 2009. Search and rescue was the toughest part in trying to solve the mystery of Flight 447’s disappearance over the Atlantic Ocean back on June 1st, 2009. Some wreckage was found a few days after the crash, but the probable cause couldn’t properly be determined until they found the black box, which took was about two years later. Of the bodies of the 228 passengers and crew, 74 remain lost in the water after the search

French investigator believes that the pilot, Dubois could have properly navigated the storm, but he was napping. “If the captain had stayed in position . . . it would have delayed his sleep by no more than 15 minutes, and because of his experience, maybe the story would have ended differently,” chief French investigator Alain Bouillard said. A search was quickly organized, but the plane sank to the ocean floor and wasn’t found for nearly two years. An oil slick thought to have been left by the downed Air France flight was spotted on June 3, 2009. Search and rescue was the toughest part in trying to solve the mystery of Flight 447’s disappearance over the Atlantic Ocean back on June 1st, 2009. Some wreckage was found a few days after the crash, but the probable cause couldn’t properly be determined until they found the black box, which took was about two years later. Of the bodies of the 228 passengers and crew, 74 remain lost in the water after the search  was finally called off.

was finally called off.

When the black box was finally found, the investigation into the crash could really begin. Flight 447 was going from Rio de Janeiro to Paris when it encountered a thunderstorm. It is now believed that the probable cause was a disconnect from autopilot due to ice crystals in the pitot tubes. With an aerodynamic stall, the crew couldn’t recover and eventually it led to the plane falling into the ocean. The inexperienced pilots did what most people would have in a stall, they pulled up. This only made the situation worse. By the time the experienced pilot got to the cockpit, it was too late to save the plane.

Over the centuries, people have gone to great lengths to humiliate their enemies. The worst thing for the Jewish people was that over the centuries, there have been so many enemies. To this day, it doesn’t matter that Israel is one of the smallest nations in the world, the Muslim nations don’t even want them to have that small area, and the Muslims weren’t the only enemy of the Jewish people either. The Jews of Europe were legally forced to wear badges or distinguishing garments, like pointed hats, to let everyone know who they were. This practice began at least as far back as the 13th century. It continued throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but was then largely phased out during the 17th and 18th centuries. With the coming of the French Revolution and the emancipation of western European Jews throughout the 19th century, the wearing of Jewish badges was abolished in Western Europe.

Over the centuries, people have gone to great lengths to humiliate their enemies. The worst thing for the Jewish people was that over the centuries, there have been so many enemies. To this day, it doesn’t matter that Israel is one of the smallest nations in the world, the Muslim nations don’t even want them to have that small area, and the Muslims weren’t the only enemy of the Jewish people either. The Jews of Europe were legally forced to wear badges or distinguishing garments, like pointed hats, to let everyone know who they were. This practice began at least as far back as the 13th century. It continued throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but was then largely phased out during the 17th and 18th centuries. With the coming of the French Revolution and the emancipation of western European Jews throughout the 19th century, the wearing of Jewish badges was abolished in Western Europe.

Enter Hitler. The Nazis, under Hitler’s direction, resurrected this practice as part of humiliation tactics during the Holocaust. Reinhardt Heydrich, chief of the Reich Main Security Office, first recommended that Jews should wear identifying badges following the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 9 and 10, 1938. Hitler liked the idea, because Hitler hated the Jews. Shortly after the invasion of Poland in September 1939, local German authorities began introducing mandatory wearing of badges. By the end of 1939, all Jews in the newly-acquired Polish territories were required to wear badges. Upon invading the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Germans again required the Jews in the newly-conquered lands to wear badges. Throughout the rest of 1941 and 1942, Germany, its satellite states and western occupied territories adopted regulations stipulating that Jews wear identifying badges. On May 29, 1942, on the advice of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler orders all Jews in occupied Paris to wear an identifying yellow star on the left side of their coats. Only in Denmark, where King Christian X is said to have threatened to wear the badge himself if it were imposed on his country’s Jewish population, were the Germans unable to impose such a regulation. Too bad some of the other nations did not stand up for the Jewish people too.

The Yellow Star was imposed on the Jewish people as part of many psychological tactics aimed at isolating and dehumanizing the Jews of Europe and especially by the Nazis. They were being directly marked as being different and inferior to everyone else. It also allowed the Germans to facilitate their separation from society and subsequent ghettoization, which ultimately led to the deportation and murder of 6 million Jews. Those who failed or refused to wear the badge risked severe punishment, including death. For example, the Jewish Council (Judenrat) of the ghetto in Bialystok, Poland announced that “… the authorities have warned that severe punishment – up to and including death by shooting – is in store for Jews who do not wear the yellow badge on back and front.” The star took on different forms in different regions, but everyone in the area knew what it

meant. Of course, the Jewish people hated the badge for what it symbolized, even though the Star of David had stood for the Jewish people since about the 12th century. While the Star of David, known as the Magen David, has continued to be the unofficial symbol of the Jewish people, even on their flag, the Menorah continues to be the official symbol of Judaism (The Jewish people). It seems to me that they would not really want the Star of David after all of the persecution that has been associated with it, but I guess it could be looked at as a badge of honor, as they, as a people survived the persecution.

meant. Of course, the Jewish people hated the badge for what it symbolized, even though the Star of David had stood for the Jewish people since about the 12th century. While the Star of David, known as the Magen David, has continued to be the unofficial symbol of the Jewish people, even on their flag, the Menorah continues to be the official symbol of Judaism (The Jewish people). It seems to me that they would not really want the Star of David after all of the persecution that has been associated with it, but I guess it could be looked at as a badge of honor, as they, as a people survived the persecution.