History

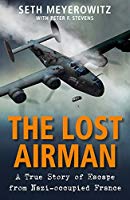

Whenever I come across a book about World War II, and especially about a B-17 Bomber, I want to read it. That subject holds my interest mostly because my dad, Allen Spencer was a top turret gunner and flight engineer on a B-17 bomber stationed at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England. Lately, I have been “reading” by way of Audible.com, and I must say that having a book read to you, allows you to sit back and enjoy it as if you were watching it unfold before your very eyes. So, when I came across a book called The Lost Airman written by Seth Meyerowitz, I knew I had to hear about it. As the true story began, I found that Arthur Meyerowitz (Seth Meyerowitz’ grandfather) could have been my own dad…at least to the extent that both of them were in the Eight Air Force stationed in England. Arthur was assigned to a B-24 Liberator. At first their experiences were probably almost identical. Arriving at his base, Arthur heard the men who had been there a while, tease the newcomers with things like “You’ll be sorry you came here” or “Look, fresh meat.” I can only imagine how that kind of thing must have felt to the new and often very young airmen…like a swift kick in the gut!! Then the book went on to tell how the airmen felt on their first mission, when no one could eat breakfast, because of the churning in their stomach. Arthur was the flight engineer and top turret gunner, just like my dad had been. It was the job of the flight engineer to check the plane over to ensure that it was fight worthy, and report to the captain. Arthur found problems with their plane, Harmful Lil Armful, and told his captain it needed repairs, but his captain wouldn’t hear of it. He was close to going home, and wanted his last mission out of the way, and besides what did this “newbie” know. He was only on his second mission, and he was filling in for someone else. So, they took off…a catastrophic decision.

Whenever I come across a book about World War II, and especially about a B-17 Bomber, I want to read it. That subject holds my interest mostly because my dad, Allen Spencer was a top turret gunner and flight engineer on a B-17 bomber stationed at Great Ashfield, Suffolk, England. Lately, I have been “reading” by way of Audible.com, and I must say that having a book read to you, allows you to sit back and enjoy it as if you were watching it unfold before your very eyes. So, when I came across a book called The Lost Airman written by Seth Meyerowitz, I knew I had to hear about it. As the true story began, I found that Arthur Meyerowitz (Seth Meyerowitz’ grandfather) could have been my own dad…at least to the extent that both of them were in the Eight Air Force stationed in England. Arthur was assigned to a B-24 Liberator. At first their experiences were probably almost identical. Arriving at his base, Arthur heard the men who had been there a while, tease the newcomers with things like “You’ll be sorry you came here” or “Look, fresh meat.” I can only imagine how that kind of thing must have felt to the new and often very young airmen…like a swift kick in the gut!! Then the book went on to tell how the airmen felt on their first mission, when no one could eat breakfast, because of the churning in their stomach. Arthur was the flight engineer and top turret gunner, just like my dad had been. It was the job of the flight engineer to check the plane over to ensure that it was fight worthy, and report to the captain. Arthur found problems with their plane, Harmful Lil Armful, and told his captain it needed repairs, but his captain wouldn’t hear of it. He was close to going home, and wanted his last mission out of the way, and besides what did this “newbie” know. He was only on his second mission, and he was filling in for someone else. So, they took off…a catastrophic decision.

This was where and similarities between Arthur’s experiences, and those of my dad ended, because my dad was not shot down like Arthur’s plane was. At the point Arthur’s plane was going down, his pilot and co-pilot showed incredible cowardice, and abandoned the plane first…something that was just not done. Arthur tried to  make sure everyone was off, but in the end, one man was stuck and injured. He told Arthur to go and take the newcomer with him, but the newcomer wouldn’t go. He fought Arthur, and actually kicked him off the plane, physically. As Arthur fell, he was sickened by the fact that his pilot and co-pilot jumped first, and that his friends would not be coming home. The pilot and co-pilot spent the rest of the war in a prison camp, but the outcome for Arthur was different, and in fact, miraculous, in more ways than one, because Arthur was not only an airman in the US Army Air Forces, but he was also a Jewish man facing the Nazis in World War II…a perilous place to be.

make sure everyone was off, but in the end, one man was stuck and injured. He told Arthur to go and take the newcomer with him, but the newcomer wouldn’t go. He fought Arthur, and actually kicked him off the plane, physically. As Arthur fell, he was sickened by the fact that his pilot and co-pilot jumped first, and that his friends would not be coming home. The pilot and co-pilot spent the rest of the war in a prison camp, but the outcome for Arthur was different, and in fact, miraculous, in more ways than one, because Arthur was not only an airman in the US Army Air Forces, but he was also a Jewish man facing the Nazis in World War II…a perilous place to be.

It was at this point in the book that my interest in it changed, because this could have been the fate of my dad, had his plane been shot down, but it hadn’t. While the outcome for Arthur was better than that of his crew mates, he still went through a harrowing experience, as did those who helped him. Arthur came down in occupied France on December 31, 1943, and in his landing, he badly hurt his back. From that point on, Arthur came in contact with some of the most amazing people on earth in that or any other time. The French resistance network took Arthur in, and over the next six months, they slowly smuggled him and a British Airman out through Spain to the Rock of Gibraltar. These people did this with precision and secrecy. They knew that if they were caught, they would be killed, but they hated the Nazis, and would do anything to fight against the Nazi regime…right up to, and for some, including giving their lives. The chances they took and the hardships they faced…voluntarily, were so far above and beyond the call of duty, that it almost seemed like a fictional movie. You know, the kind where the good guys always win, and the bad guys always lose. Nevertheless, this wasn’t a fictional movie, and the lives lost were real, but Arthur  Meyerowitz was not among the lives lost. His was saved because of the selfless acts of so many people in the French Resistance. The story of Arthur Meyerowitz was, for me, so moving that in the end, I cried, and throughout the book, there were moments that I could hardly breathe with the tension of the situations they found themselves in. I felt bad to think it, but I was so thankful that my dad’s B-17 always made it home, and he never had to face the prison camps, or try to escape from a hostile nation. For Arthur, his escape was miraculous, and I believe it was because of the fervent prayers of his family and the undying faith of his mother, who believed that God would bring her son home…and God did.

Meyerowitz was not among the lives lost. His was saved because of the selfless acts of so many people in the French Resistance. The story of Arthur Meyerowitz was, for me, so moving that in the end, I cried, and throughout the book, there were moments that I could hardly breathe with the tension of the situations they found themselves in. I felt bad to think it, but I was so thankful that my dad’s B-17 always made it home, and he never had to face the prison camps, or try to escape from a hostile nation. For Arthur, his escape was miraculous, and I believe it was because of the fervent prayers of his family and the undying faith of his mother, who believed that God would bring her son home…and God did.

My grandfather, George Byer was a man of gentle strength. Many people may not think those to traits go together, but in him they did. He was always a hard-working man, who gave his all to support his family, but maybe the gentleness came partly from the fact that he had 9 children, 7 of whom were girls. That can make a man understand that girls are often the fairer gender, at least in those days. Grandpa Byer lived in a time when the women stayed home and raised the family and the men went out and made the living…even if that meant working long hours or multiple jobs. Grandpa also lived during the great depression, when jobs were scarce, so the women need not have bothered to go look for one very often.

My grandfather, George Byer was a man of gentle strength. Many people may not think those to traits go together, but in him they did. He was always a hard-working man, who gave his all to support his family, but maybe the gentleness came partly from the fact that he had 9 children, 7 of whom were girls. That can make a man understand that girls are often the fairer gender, at least in those days. Grandpa Byer lived in a time when the women stayed home and raised the family and the men went out and made the living…even if that meant working long hours or multiple jobs. Grandpa also lived during the great depression, when jobs were scarce, so the women need not have bothered to go look for one very often.

While times were tough sometimes, the family really never wanted for much, and grandma, Hattie Byer could somehow make the meager portions of food go a long way, and still never turn  away a stranger in need of a meal, and it seemed there was always a plentiful supply of those strangers and friends who would come for dinner at the Byer house. They were a good team, and truth be told, Grandma Byer was probably just as tough, if not more so than Grandpa Byer, who did have a definite soft spot in his heart for people. Grandpa worked at a number of jobs, but the one I probably heard the most about was the building of Alcova Dam Grandpa had also worked on Kortez Dam and Pathfinder Dam, but my mom, Collene Spencer, who was Grandpa’s middle child, always mentioned to us that her dad had helped build Alcova Dam, every time we drove past it. She was very proud of her dad, and with good reason, because he was very special.

away a stranger in need of a meal, and it seemed there was always a plentiful supply of those strangers and friends who would come for dinner at the Byer house. They were a good team, and truth be told, Grandma Byer was probably just as tough, if not more so than Grandpa Byer, who did have a definite soft spot in his heart for people. Grandpa worked at a number of jobs, but the one I probably heard the most about was the building of Alcova Dam Grandpa had also worked on Kortez Dam and Pathfinder Dam, but my mom, Collene Spencer, who was Grandpa’s middle child, always mentioned to us that her dad had helped build Alcova Dam, every time we drove past it. She was very proud of her dad, and with good reason, because he was very special.

Grandpa served in the Army during World War I as a cook. While he was very brave, and never a man to shirk his duties, I think it would have been hard for this gentle soul to have a military career of killing people. Nevertheless, had the need arisen, he would have done it, because he always knew that he would protect those in his charge. He was a very loyal soldier, and he would never have allowed those he cared about to be killed, if he could stop it. His gentle strength was, for me, his trademark trait. I remember it from my childhood as clearly as if Grandpa Byer were standing right next to me as I write this story. he was the sweetest, kindest, most gentle man anyone could have known. Today would have been my Grandpa Byer’s 126th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandpa. We love and miss you very much!!

Grandpa served in the Army during World War I as a cook. While he was very brave, and never a man to shirk his duties, I think it would have been hard for this gentle soul to have a military career of killing people. Nevertheless, had the need arisen, he would have done it, because he always knew that he would protect those in his charge. He was a very loyal soldier, and he would never have allowed those he cared about to be killed, if he could stop it. His gentle strength was, for me, his trademark trait. I remember it from my childhood as clearly as if Grandpa Byer were standing right next to me as I write this story. he was the sweetest, kindest, most gentle man anyone could have known. Today would have been my Grandpa Byer’s 126th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandpa. We love and miss you very much!!

Gunfighters were a big part of what we think of when we think of the Old West. The reality is that there were probably a lot less gunfights that we have been led to believe, and most were not held in the way that we all think. Many were quickly started when tempers flared, and then over in a moment. The whole meeting on “Main Street at high noon” thing didn’t happen very much. Nevertheless, gunfighters were a part of the Old West and many were truly mean and evil people.

Gunfighters were a big part of what we think of when we think of the Old West. The reality is that there were probably a lot less gunfights that we have been led to believe, and most were not held in the way that we all think. Many were quickly started when tempers flared, and then over in a moment. The whole meeting on “Main Street at high noon” thing didn’t happen very much. Nevertheless, gunfighters were a part of the Old West and many were truly mean and evil people.

William “Texas Billy” Thompson (1845-1897), was the brother of the more famous gunman Ben Thompson. Apparently Billy felt the need to live up to an surpass his brother’s reputation. Billy was often described as “mean, vicious, vindictive and totally unpredictable.” Billy and his brother, Ben emigrated from Yorkshire, England with their family to Austin, Texas in 1851, when he was just a boy. When the Civil War began, both men enlisted in the Texas Mounted Rifles. After the war, there were a number of federal troops who remained in Texas for several years, which annoyed the people of Texas. In March, 1868, Billy was involved in a gunfight with a Private William Burk. After killing the soldier, Billy fled the area. Two months later, Billy killed another man in Rockport, Texas and when a warrant was issued for his arrest, he was on the run again, first to Indian Territory and then to Kansas.

While in Abilene, Kansas, Billy met a dance hall girl and prostitute named Elizabeth “Libby” Haley. Haley went by the alias of “Squirrel Tooth Alice.” The two quickly began an affair that would eventually lead to marriage and nine children. Billy made his living as a gambler. He and his brother Ben, were living in Ellsworth, Kansas in April, 1873. Four months later, in August, Billy’s temper got the best of him again, and killed Sheriff Chauncey Whitney. He was on the run again.

Billy had a reputation for constantly being trouble for one thing or another. This meant that Billy and Libby were constantly moving. The Texas Rangers finally caught up with Billy in October 1876, and was extradited to Kansas. Amazingly, he was acquitted of the murder of Sheriff Whitney. He must have had a great attorney, because everyone knew he did it. Billy made his way to Dodge City, Kansas. There is also evidence that places him in Colorado and Nebraska, before he and Libby finally settled down in Sweetwater, Texas. He purchased and worked a ranch, while she established a brothel in town. In 1884, he was reportedly in San Antonio and witnessed his brother being gunned down by assassins. Billy took no revenge on his brother’s killers. Maybe he had lost his taste for killing and running. On September 6, 1897, William Thompson died from a stomach ailment at the age of 52.

The Gold Rush affected many states and many people. Everyone headed west to try their luck, hoping to strike it rich. While the big strikes seemed to be in California, the Black Hills, and Alaska, there were many other places where miners struck it rich…and just as many where the miners went bust. It takes a special group of people to persevere in the gold rush years, and many went home broke, or found another way to cash in on the god rush, such as stores where the miners could buy supplies, or saloons, where they could drown their sorrows.

The Gold Rush affected many states and many people. Everyone headed west to try their luck, hoping to strike it rich. While the big strikes seemed to be in California, the Black Hills, and Alaska, there were many other places where miners struck it rich…and just as many where the miners went bust. It takes a special group of people to persevere in the gold rush years, and many went home broke, or found another way to cash in on the god rush, such as stores where the miners could buy supplies, or saloons, where they could drown their sorrows.

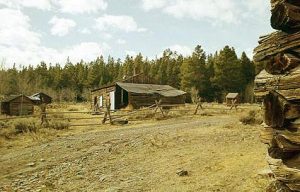

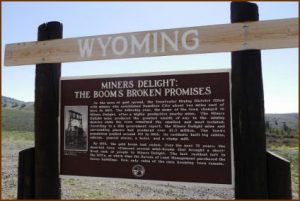

Wyoming had it’s share of gold mines and gold strikes too. Atlantic City was located in west central Wyoming, it was one of three mining towns in the area. The others were South Pass City, and Hamilton City. These towns sprung up as a result of the gold discovery at Spring Gulch in 1867. Hamilton City is located about three miles east of Atlantic City, but it could prove very difficult to locate, because early on in the town’s history, the townspeople unofficially renamed it to Miners Delight after the area’s largest and most productive mine, which carried the same name and was located on Peabody Hill.

The Miners Delight mine was founded by Jonathan Pugh. After a while, the town was officially changed to Miners Delight, since no one called it Hamilton City anyway. At first the mine was a rich enough producing mine to warrant a 10-stamp mill to be erected to crush the rock. The first mention of the town in newspapers appeared in July 1868 with the Sweetwater Mines newspaper describing it as: “…some thirty buildings are up, and more in course of construction. Spring Gulch is turning out the bright ore in very comfortable quantities,” and continues “Ten companies are at work in Spring Gulch…and all appear content with the result of their labors.”

Strangely, the owners of the Miners Delight mine found that recovering gold is more expensive than the gold is worth. After a short few years, the town’s population fell dramatically from its peak of some 75 residents. The Miners Delight Mine shut down in 1874, but soon reopened again…only to close again in 1882. The mining camp would endure good times and bad times over the next several decades, including the Great Depression. Over the years the mine produced over $5 million in gold ore…a relatively small amount as gold goes. The town was inhabited as late as 1960, but today it is nothing but abandoned ruins.

If you go there, you can expect to see rusting iron equipment, such as this old stove, and a couple of iron box screens, around the cabins of Miners Delight, Wyoming. It all seems like nothing much, but in the town’s heyday, it was even home to a couple of famous residents. Henry Tompkins Paige Comstock, would later discover the famous Comstock Lode in Nevada, and a young orphaned girl named Martha Jane Canary, who became known a Calamity Jane. As a child, Marth was adopted and moved with her new parents to Miners Delight. She liked the wild life in both Atlantic City and Miners Delight, and then in Deadwood, South Dakota.

Today, the site is located on Bureau of Land Management property. Some preservation work has been done in order to keep the few remaining buildings standing, but the site is not being restored. Miners Delight is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The site continues to preserve several cabins, one building that was said to have been a saloon, a baker, a barn, and a couple of outhouses. They are the last remnants of a long ago era.

Today, the site is located on Bureau of Land Management property. Some preservation work has been done in order to keep the few remaining buildings standing, but the site is not being restored. Miners Delight is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The site continues to preserve several cabins, one building that was said to have been a saloon, a baker, a barn, and a couple of outhouses. They are the last remnants of a long ago era.

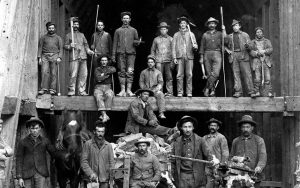

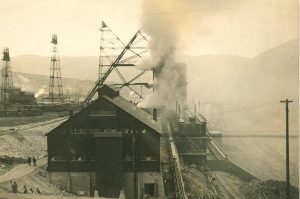

It is in times of greatest need, that people seem to best show that they can pull together to accomplish the greatest tasks. During World War I, the city of Butte, Montana was already a unionized industrial city with a population of 91,000 people. The city was home to one of the largest mining operations in the world. Butte was home to a copper mine system consisting of the Granite Mountain and Speculator Mines, and because of the heightened need for copper at that time, the abundance of employment opportunities drew workers from every corner of the world. The influx of people from other corners meant that more than 30 languages were spoken among the city streets. “No Smoking” signs posted in the mines were printed in 16 different languages, so that there was no mistaking the dangers.

It is in times of greatest need, that people seem to best show that they can pull together to accomplish the greatest tasks. During World War I, the city of Butte, Montana was already a unionized industrial city with a population of 91,000 people. The city was home to one of the largest mining operations in the world. Butte was home to a copper mine system consisting of the Granite Mountain and Speculator Mines, and because of the heightened need for copper at that time, the abundance of employment opportunities drew workers from every corner of the world. The influx of people from other corners meant that more than 30 languages were spoken among the city streets. “No Smoking” signs posted in the mines were printed in 16 different languages, so that there was no mistaking the dangers.

In April of 1917, the United States’ involvement in World War I was in its fourth month, and Butte mines increased their production of copper by operating around the clock, working the 14,500 miners like mules in order to meet the ever increasing demand. Unfortunately, this also brought steadily deteriorating safety conditions. Many of the miners were sleeping in shifts, so the beds in the boarding houses often never went cold. Despite these demanding work conditions, Butte miners worked with a pride and determination seldom found above ground, let alone a half-mile below the surface of the earth. They felt the weight of their duty to the war effort, and they gladly performed their jobs to the best of their abilities. Each day, the men were lowered into the mine, and the previous crew was brought out.

On the evening of June 8, 1917, 410 men were lowered into the Granite Mountain shaft to begin another backbreaking night shift. The exiting day shift had been tasked with the process of lowering a three-ton electric  cable down the shaft to complete work on a sprinkler system designed to protect the mine against fire. All seemed to be going well, but at 8:00 pm the cable slipped from its clamps. As it fell into a tangled coil below the 2400 foot level of the mine, the lead covering was torn away. The torn covering exposed a large portion of oiled paraffin paper, which was used to insulate the cable. Unfortunately, the oiled paraffin paper was also highly flammable. At 11:30 pm four men went down to examine the cable. One of the men accidentally touched his handheld carbide lamp to the oiled paraffin insulation, which immediately ignited. The flame spread quickly to the shaft timbers. The Granite Mountain and Speculator shafts immediately filled with thick, toxic smoke.

cable down the shaft to complete work on a sprinkler system designed to protect the mine against fire. All seemed to be going well, but at 8:00 pm the cable slipped from its clamps. As it fell into a tangled coil below the 2400 foot level of the mine, the lead covering was torn away. The torn covering exposed a large portion of oiled paraffin paper, which was used to insulate the cable. Unfortunately, the oiled paraffin paper was also highly flammable. At 11:30 pm four men went down to examine the cable. One of the men accidentally touched his handheld carbide lamp to the oiled paraffin insulation, which immediately ignited. The flame spread quickly to the shaft timbers. The Granite Mountain and Speculator shafts immediately filled with thick, toxic smoke.

There was a mad scramble to find a way of escape. Just over half of the men working in the Granite Mountain shaft were able to find an escape to the surface. One group of 29 men built a bulkhead to isolate themselves from the smoke and gas. They stayed there for 38 hours before making their way to safety. At the 2254 foot level, another group of 8 men were found behind a makeshift bulkhead over 50 hours from the start of the fire. Two of these men died shortly before their rescue, but the other six were recovered safely. Though the intensity of the fire cannot be disputed, only two men were actually burned to death in a rescue attempt at the onset of the blaze. The rest were simply trapped and overcome by the noxious, suffocating fumes. By the close of the rescue operation on June 16, 1917, eight days after the fire had begun, the death toll had reached its final tally of 168 men.

The Granite Mountain and Speculator Mine Fire was the worst disaster in metal mining history. And we could leave it at that, but then we would be overlooking a remarkable accomplishment…the rescue mission. Over the  course of just 7 days, rescue crews succeeded in searching over 30 miles of drifts and crosscuts, and at least 15 miles of stopes, raises, and manways. Townspeople turned out in droves to help in whatever way the could. All this was done in mine shafts saturated with carbon monoxide and dense, tar-laden smoke. In all, 155 bodies were recovered and removed, all without the loss of a single rescue worker. Despite the tremendous damage the fire caused to the Granite Mountain Mine, it did not stop the work being done there. Copper ore continued to be mined until the mine’s close in 1923. The Butte mines produced the copper that helped electrify America and win World War I. Through this horrible tragedy, Butte received a very special moniker. The city was being called “The Richest Hill on Earth, referencing the soul and determination of the community, rather than the value of the ore beneath its feet.”

course of just 7 days, rescue crews succeeded in searching over 30 miles of drifts and crosscuts, and at least 15 miles of stopes, raises, and manways. Townspeople turned out in droves to help in whatever way the could. All this was done in mine shafts saturated with carbon monoxide and dense, tar-laden smoke. In all, 155 bodies were recovered and removed, all without the loss of a single rescue worker. Despite the tremendous damage the fire caused to the Granite Mountain Mine, it did not stop the work being done there. Copper ore continued to be mined until the mine’s close in 1923. The Butte mines produced the copper that helped electrify America and win World War I. Through this horrible tragedy, Butte received a very special moniker. The city was being called “The Richest Hill on Earth, referencing the soul and determination of the community, rather than the value of the ore beneath its feet.”

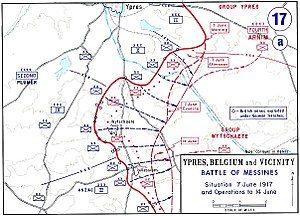

World War I found the British Army with a big problem. The German 4th Army was deeply entrenched at Messines Ridge in northern France, and the British had to remove them…somehow. The British came up with a plan, and for the 18 months prior to June 7, 1917, soldiers had been secretly working to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the German stronghold positions were located. The plan was put into action by the British 2nd Army under the supervision of General Sir Herbert Plumer. The joint explosion of the mines at Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”.

World War I found the British Army with a big problem. The German 4th Army was deeply entrenched at Messines Ridge in northern France, and the British had to remove them…somehow. The British came up with a plan, and for the 18 months prior to June 7, 1917, soldiers had been secretly working to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the German stronghold positions were located. The plan was put into action by the British 2nd Army under the supervision of General Sir Herbert Plumer. The joint explosion of the mines at Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”.

On June 7, 1917, they were ready to carry out their secret attack. The explosions created 19 large craters. It would be a crushing victory over the Germans who had no idea of the impending disaster they were about to face. This attack would mark the successful beginning of an Allied offensive designed to break the grinding stalemate on the Western Front in World War I. The time of the attack was set for 3:10am. Precisely on schedule, a series of simultaneous explosions rocked the area. The blast from the detonation of all those landmines was heard as far away as London. A German observer described the explosions, “nineteen gigantic roses with carmine petals, or enormous mushrooms, rose up slowly and majestically out of the ground and

then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

Although Messines Ridge battle was, itself was a relatively limited victory, it had a considerable effect on the German morale. The Germans were forced to retreat to the east, a sacrifice that marked the beginning of their gradual, but continuous loss of territory on the Western Front. It also secured the right flank of the British thrust towards the highly contested Ypres region, which was the eventual objective of the planned offensive. Over the next month and a half, British forces continued to push the Germans back toward the high ridge at Passchendaele, which on July 31 saw the launch of the British offensive known as the Battle of Passchendaele. The Battle of Messines marked the high point of mine warfare. On August 10, 1917, the Royal Engineers fired the last British deep mine of the war, at Givenchy-en-Gohelle near Arras.

The explosions left a mine crater 40 feet deep. The attack had done its job. Still, after the war was over, the crater remained, and some wanted to change the “feel” of the place. Nowadays, this mine crater is a serene, contemplative place. I’m sure that many who visit there feel the significance of the location, but also know just  how necessary it was to ensure the freedom of France from the tyranny of the German forces. Named The Pool of Peace, it is a 40 foot deep lake near Messines, Belgium. It fills one of the craters made in 1917 when the British detonated a mine containing 45 tons of explosives. The pool stretches 423 feet across, and remains a place of solace that receives many visitors every year. It seems to me that, while most of those killed in the mine fields on June 7, 1917, were Germans, and therefore, the enemy, they were also people, many of whom didn’t want to be there any more than the Allies did. They were there under orders, and that was all there was to it. For that reason, I believe that place should be, finally, a place of peace.

how necessary it was to ensure the freedom of France from the tyranny of the German forces. Named The Pool of Peace, it is a 40 foot deep lake near Messines, Belgium. It fills one of the craters made in 1917 when the British detonated a mine containing 45 tons of explosives. The pool stretches 423 feet across, and remains a place of solace that receives many visitors every year. It seems to me that, while most of those killed in the mine fields on June 7, 1917, were Germans, and therefore, the enemy, they were also people, many of whom didn’t want to be there any more than the Allies did. They were there under orders, and that was all there was to it. For that reason, I believe that place should be, finally, a place of peace.

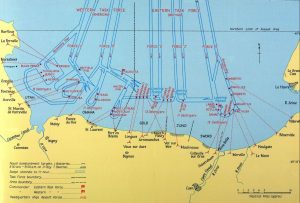

Most people from the Baby Boomer Generation know the significance of D-Day, but it occurs to me that many people in the younger generations may not really know what it was all about. Operation Overlord was the Allied invasion of northern France, commonly known as D-Day. The operation was under the direction of Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The operation had a brief 3 day window in which to take place, and June 5th had been chosen to be the day, but the day dawned gloomy, so the operation had to be scrubbed for the day.

Most people from the Baby Boomer Generation know the significance of D-Day, but it occurs to me that many people in the younger generations may not really know what it was all about. Operation Overlord was the Allied invasion of northern France, commonly known as D-Day. The operation was under the direction of Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The operation had a brief 3 day window in which to take place, and June 5th had been chosen to be the day, but the day dawned gloomy, so the operation had to be scrubbed for the day.

Then on June 6th, the orders came down that Operation Overlord was a go. By daybreak, 18,000 British and American parachutists were already on the ground. An additional 13,000 aircraft were mobilized to provide air cover and support for the invasion, among them the B-17, Raggedy Ann, which was carrying my dad, Allen Spencer, who was a Top Turret Gunner and Flight Engineer. At 6:30 am, American troops came ashore at Utah and Omaha beaches. The British and Canadians overcame light opposition to capture Gold, Juno and Sword beaches, as did the Americans at Utah. Omaha beach was a much different situation, however, where the US First Division battled high seas, mist, mines, burning vehicles, and German coastal batteries, including an elite infantry division, which spewed heavy fire. Many wounded Americans ultimately drowned in the high tide. British divisions, which landed at Gold, Juno, and Sword beaches, and Canadian troops also met with heavy German fire.

The troops persevered, even though the loses were great, and in the end the operation was declared a victory. There were many reasons that D-Day was successful, even against all odds. The Allies had fooled the Germans, who thought the attack was going to occur farther along the coast at Calais because this was the shortest route by sea, even when the attack began on the beaches Hitler was still convinced the attack was going to occur at Calais. What a shock that must have been when he found out that the attack took place on the beaches of Normandy. False intelligence spread by the allies spread false information to the Germans, and they bought it.

There were many factors that all worked together to make the plan work. Wooden guns on the South Coast of England, wooden planes, dropped plastic dummies out of planes, they put mirrors up on their ships and the Germans were fooled as they saw themselves going the other way. New technology specifically designed for the landing enabled the Allies to gain an advantage over the Germans. Mulberries, the floating docks the Allies used to land, enabled the Allies to land safely and disembark while firing. Some of the beaches were practically empty, however, on Omaha beach the Allies suffered heavy losses numbering 2000 in total. Operation Overlord had been planned for many years and so they were ready. The Germans had to keep control of the other parts of their empires, so their troops were elsewhere. Hitler denied that his forces were losing in Normandy, and  would not authorize the mobilization of forces stationed near Normandy.

would not authorize the mobilization of forces stationed near Normandy.

As for the Allies, the troops involved were highly trained, equipped and motivated. Their battle plan was well prepared. All the necessary manpower and logistics were available to them. The air space was controlled by the Allies. The sea lanes were very short and the seas were in Allied hands. The deception plan was flawless. The Germans had no idea what was coming. The French Resistance was highly effective. The German troop who were there were poorly motivated. Hitler’s Defense Planning was completely flawed. But, the biggest victory is that the troops did their job.

The Japanese had a tendency to be sneaky about their weapons of warfare, and their attack plans, as we know from Pearl Harbor. One such well kept secret was the Hiryu…which means Flying Dragon. The ship was a modified Soryu design that was built exclusively for the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Soryu, which means Blue Dragon, was built first, and because of the heavy modifications, the Hiryu was almost considered to be a separate class of ship. Hiryu had a displacement of 17,600 tons, length of 746 feet 1 inch, beam of 73 feet 2 inches, draft of 25 feet 7 inches and a speed of 34 knots. Built in 1931, “these two ships became prototypes for almost all subsequent Japanese carriers. They had continuous flight deck, two-level hangar, small island superstructure, two deflexed down and aft funnels and three elevators. As a whole ship design (within the limits of displacement assigned on it) has appeared rather successful, harmoniously combining high speed with strong AA armament and impressive number of air group.” The Hiryu, unlike the small height hangar levels of the Soryu, was built to an advanced design. “Her freeboard height was increased by one deck, island was transferred to a port side (Hiryu became second after Akagi and last Japanese carrier with an island on a port side). Breadth of a flight deck was increased on 1m, a fuel stowage on 20%. She had a little strengthened protection: belt thickness abreast machinery raised to 48mm.”

The Japanese had a tendency to be sneaky about their weapons of warfare, and their attack plans, as we know from Pearl Harbor. One such well kept secret was the Hiryu…which means Flying Dragon. The ship was a modified Soryu design that was built exclusively for the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Soryu, which means Blue Dragon, was built first, and because of the heavy modifications, the Hiryu was almost considered to be a separate class of ship. Hiryu had a displacement of 17,600 tons, length of 746 feet 1 inch, beam of 73 feet 2 inches, draft of 25 feet 7 inches and a speed of 34 knots. Built in 1931, “these two ships became prototypes for almost all subsequent Japanese carriers. They had continuous flight deck, two-level hangar, small island superstructure, two deflexed down and aft funnels and three elevators. As a whole ship design (within the limits of displacement assigned on it) has appeared rather successful, harmoniously combining high speed with strong AA armament and impressive number of air group.” The Hiryu, unlike the small height hangar levels of the Soryu, was built to an advanced design. “Her freeboard height was increased by one deck, island was transferred to a port side (Hiryu became second after Akagi and last Japanese carrier with an island on a port side). Breadth of a flight deck was increased on 1m, a fuel stowage on 20%. She had a little strengthened protection: belt thickness abreast machinery raised to 48mm.”

Hiryu took part in Japanese invasion of French Indochina (Now Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) in mid 1940s, the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Wake Island. The ship became a great enemy of the Allies. Then, along with three other fleet carriers, Hiryu participated in the Battle of Midway Atoll in North Pacific Ocean in June 1942. Initially, the Japanese forces managed to bombard US forces on the atoll. It didn’t look good for the  Allies, but on June 4, 1942, the Japanese aircraft carriers were attacked by dive-bomber aircraft from USS Enterprise, USS Yorktown, USS Hornet, and Midway Atoll. Hiryu was hit and severely crippled, and was set on fire. Japanese destroyer Makigumo torpedoed Hiryu on June 5, 1942 at 05:10 am, because she could not be salvaged. Only 39 men survived as after 4 hours, she sank with bodies of 389 men. Three other Japanese carriers were also sunk during the Battle of Midway. It was a battle that brought Japan’s first naval defeat since the Battle of Shimonoseki Straits in 1863. It was a great day for the Allies.

Allies, but on June 4, 1942, the Japanese aircraft carriers were attacked by dive-bomber aircraft from USS Enterprise, USS Yorktown, USS Hornet, and Midway Atoll. Hiryu was hit and severely crippled, and was set on fire. Japanese destroyer Makigumo torpedoed Hiryu on June 5, 1942 at 05:10 am, because she could not be salvaged. Only 39 men survived as after 4 hours, she sank with bodies of 389 men. Three other Japanese carriers were also sunk during the Battle of Midway. It was a battle that brought Japan’s first naval defeat since the Battle of Shimonoseki Straits in 1863. It was a great day for the Allies.

The current generation of kids probably have no idea what a phone booth is, besides maybe a place for Superman to change into his costume. From the time phones first became something that was provided to the public for a fee, phone booths became a common sight on city streets. Then in the 1950s, a new fad began. Much like the fad of stuffing as many people as possible into a car, people decided to stuff as many people as possible into a phone booth. My guess is that like most of these strange fads, this one too,

The current generation of kids probably have no idea what a phone booth is, besides maybe a place for Superman to change into his costume. From the time phones first became something that was provided to the public for a fee, phone booths became a common sight on city streets. Then in the 1950s, a new fad began. Much like the fad of stuffing as many people as possible into a car, people decided to stuff as many people as possible into a phone booth. My guess is that like most of these strange fads, this one too,  was practiced mostly by young people.

was practiced mostly by young people.

Phone booth stuffing first gained popularity outside the United States, but once it arrived stateside, in spring 1959, kids couldn’t help but join in. Basically, people would cram their bodies into the narrow spaces like sardines in a can. Some adopted other methods, such as stacking themselves horizontally. Just imagine being the guy on the bottom of the stack. All I can say is, “Hurry up, because I can’t breathe!!”

As with so many other crazy fad, phone booth stuffing became something to set a world record for. People began trying to outdo the prior record. The word record for phone-booth stuffing came in March 1959, when 25 people in South Africa piled into a booth. I can’t imagine how they could possibly fit 25 people in a phone booth, but while they were all in there, the phone rang. Of course, nobody answered the phone, because nobody could move enough to reach it. Sadly, the trend died by the end of 1959. Of course, that doesn’t mean that some of the other stuffing trends didn’t continue. I think people are still stuffing as many people as they can into a car. I just hope they don’t try to drive that way.

As with so many other crazy fad, phone booth stuffing became something to set a world record for. People began trying to outdo the prior record. The word record for phone-booth stuffing came in March 1959, when 25 people in South Africa piled into a booth. I can’t imagine how they could possibly fit 25 people in a phone booth, but while they were all in there, the phone rang. Of course, nobody answered the phone, because nobody could move enough to reach it. Sadly, the trend died by the end of 1959. Of course, that doesn’t mean that some of the other stuffing trends didn’t continue. I think people are still stuffing as many people as they can into a car. I just hope they don’t try to drive that way.

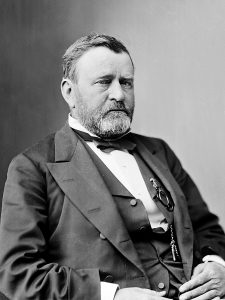

Often we think that the best course of action is to simply attack a problem head on, but that is not always true, as Union General Ulysses S. Grant would find out on June 3, 1864. The United States was deep into the Civil War, and on that particular day, and the Confederate Army was entrenched at Cold Harbor, Virginia. General Grant was about to make the greatest mistakes of his career.

Often we think that the best course of action is to simply attack a problem head on, but that is not always true, as Union General Ulysses S. Grant would find out on June 3, 1864. The United States was deep into the Civil War, and on that particular day, and the Confederate Army was entrenched at Cold Harbor, Virginia. General Grant was about to make the greatest mistakes of his career.

Since the battle began on May 31st, Grant’s Army of the Potomac and Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had inflicted frightful losses upon each other as they worked their way around Richmond, Virginia…from the Wilderness forest to Spotsylvania and numerous smaller battle sites…the previous month. On May 30, Lee and Grant collided  at Bethesda Church. The next day the battle began when the advance units of the armies arrived at the crossroads of Cold Harbor, which was just 10 miles from Richmond, Virginia. There, a Yankee attack seized the intersection. Grant decided that this was the perfect chance to destroy Lee at the gates of Richmond, Grant prepared for a major assault along the entire Confederate front on June 2nd, but his plan was delayed because the necessary troops…Winfield Hancock’s Union corps did not arrive on schedule, the operation was delayed until the following day.

at Bethesda Church. The next day the battle began when the advance units of the armies arrived at the crossroads of Cold Harbor, which was just 10 miles from Richmond, Virginia. There, a Yankee attack seized the intersection. Grant decided that this was the perfect chance to destroy Lee at the gates of Richmond, Grant prepared for a major assault along the entire Confederate front on June 2nd, but his plan was delayed because the necessary troops…Winfield Hancock’s Union corps did not arrive on schedule, the operation was delayed until the following day.

The delay was a tragic move for the Union army, because it gave Lee’s troops time to entrench. Grant was frustrated with the prolonged pursuit of Lee’s army, so he gave the order to attack on June 3, but the entrenched Confederate army had the protection of deep trenches atop a hill, making the Union army have to attack without cover. It was a decision that resulted in a complete disaster. The Yankees were met with murderous fire, and were only able to reach the Confederate trenches in a few places. The 7,000 Union casualties, compared to only 1,500 for the Confederates, were all lost in under an hour. A dejected Grant pulled out of Cold Harbor nine days later and continued to try to flank Lee’s army. His next stop was Petersburg, south of Richmond, where he forced a nine-month siege. While Petersburg would redeem him some, there would be no more attacks on the scale of Cold Harbor.