Caryn

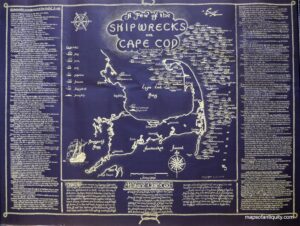

The dangers of the Cape Cod shoals are well known to the seamen who regularly navigate those waters. Almost from the time the shoals were discovered, they have been wreaking havoc on the ships that have the misfortune of getting too close to them. Sailors know that they need to steer clear of the Cape coast. Thousands of ships have been destroyed on its bars and rocks, and with the lost ships, uncounted lives too have been lost in the storm-tossed waves. When the storms were raging and a ship got caught, there was no way for rescuers to get to the trapped crew and passengers. The storms battered the trapped ships until they sank.

The dangers of the Cape Cod shoals are well known to the seamen who regularly navigate those waters. Almost from the time the shoals were discovered, they have been wreaking havoc on the ships that have the misfortune of getting too close to them. Sailors know that they need to steer clear of the Cape coast. Thousands of ships have been destroyed on its bars and rocks, and with the lost ships, uncounted lives too have been lost in the storm-tossed waves. When the storms were raging and a ship got caught, there was no way for rescuers to get to the trapped crew and passengers. The storms battered the trapped ships until they sank.

Oddly, Cape Cod is both a hazard and a haven to the mariners. All shipping between Boston and New York must either pass into its sheltered bay or run aground on its treacherous shoals. It is only the skill of the mariners that determines the difference. The shoals, when combined with the forces of  countless Nor’easters put the Cape in a precarious location. Because of this, the Cape has been the site of more than 3,000 shipwrecks in 300 years of recorded history.

countless Nor’easters put the Cape in a precarious location. Because of this, the Cape has been the site of more than 3,000 shipwrecks in 300 years of recorded history.

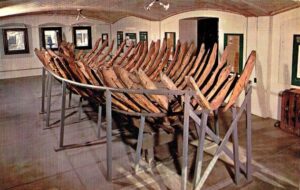

One of the first recorded wrecks was that of the Sparrow Hawk. The Sparrow Hawk originally hailed from London, England. It was making a six-week voyage to Virginia when it ran aground off Nauset Harbor in 1626. A gale arose and forced the vessel over the bar into the harbor. The ship ran aground near Orleans. The area isn’t always so dangerous. When the tide is low, people aboard the ships were able to get ashore safely when their ships ran aground. When Sparrow Hawk grounded, some English-speaking Indians arrived and offered to conduct them to Plymouth or carry a message. Grateful, they accepted and once ashore, they sent a message which brought Governor William Bradford with repair material. The ship was soon repaired, but before it could set sail, the ship was sunk by another storm. The sunken ship was abandoned.

The second wreck would be more permanent, as the ship wasn’t seen for over 200 years. The wreckage reappeared on May 6, 1863, after the sand shifted. The exposed remains of the ship reappeared only briefly. Because of the vessel’s unusual shape, two local men made a drawing of it. The ship was an oddity, and it drew many visitors. The visitors, when they came to see, nearly all took a fragment of the ship for a souvenir before it was again covered by sand in August of 1863. Since they now knew where the ship was, it has since been excavated, and the ribs of the ship were removed and transferred to the Pilgrim Hall Museum in Plymouth, where it is to this day.

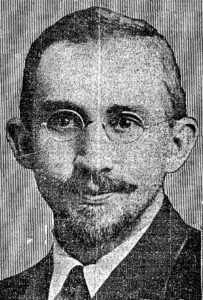

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

In any war, there must be a nation’s first casualty. World War I could be no different. On March 28, 1915, the first American citizen was killed in the eighth month of World War I. The United States didn’t even enter the war until April 6, 1917. Nevertheless, Leon Thrasher, who was a 31-year-old mining engineer and a native of Massachusetts, drowned when a German U-Boat, the U-28 torpedoed a cargo-passenger ship the British RMS Falaba, a West African steamship, on which Thrasher was a passenger. The sinking became known as “The Thrasher Incident.” The RMS Falaba was on its way from Liverpool to West Africa, off the coast of England. Of the 242 passengers and crew on board RMS Falaba, 104 drowned. Thrasher was employed on the Gold Coast in British West Africa, and on March 28, 1915, he was on the RMS Falaba, as a passenger, returning to his post, following a trip to England.

The sinking, brought with it a claim from the Germans that the submarine’s crew had  followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave

followed all protocol when approaching RMS Falaba. The Germans said that they gave the passengers ample time to abandon ship, and that they fired only when British torpedo destroyers began to approach to give aid to the Falaba. Of course, the British official press report of the incident disagreed, claiming that the Germans had acted improperly, “It is not true that sufficient time was given the passengers and the crew of this vessel to escape. The German submarine closed in on the Falaba, ascertained her name, signaled her to stop, and gave  those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

those on board five minutes to take to the boats. It would have been nothing short of a miracle if all the passengers and crew of a big liner had been able to take to their boats within the time allotted.”

The sinking of RMS Falaba, and Thrasher’s subsequent death, was mentioned again in a memorandum sent by the US government, which was drafted by President Woodrow Wilson himself and addressed to the German government after the German submarine attack on the British passenger ship Lusitania on May 7, 1915, in which 1,201 people were drowned, including 128 Americans. President Wilson’s note was clearly a warning, calling for the US and Germany to come to a full and complete understanding as to the grave situation which had resulted from the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. In response to the warning, Germany abandoned the policy shortly thereafter. However, the policy abandonment was reversed in early 1917, and that was the final straw that put the United States into World War I on April 6, 1917.

This year has been one of so much change for my niece, Amanda Reed. The biggest change is that Jadyn Mortensen, the daughter that she shares with partner, Sean Mortensen went away to college. It wasn’t that she was so far away, but because she is their only child, her leaving brought not only their first college student, but also the empty nest syndrome. They are a very close family. They all share a love of all things outdoor sports. Jadyn is even attending the University of Wyoming on a full ride rodeo scholarship. From boating, to snowmobiling, to skiing, to motorcycling, to horse riding, this is a family of athletes, and they do it all together. So having Jadyn in college, leaves a big hole in the family dynamic, and they are all feeling it. The good news is that summer is coming, and Jadyn’s break from college.

This year has been one of so much change for my niece, Amanda Reed. The biggest change is that Jadyn Mortensen, the daughter that she shares with partner, Sean Mortensen went away to college. It wasn’t that she was so far away, but because she is their only child, her leaving brought not only their first college student, but also the empty nest syndrome. They are a very close family. They all share a love of all things outdoor sports. Jadyn is even attending the University of Wyoming on a full ride rodeo scholarship. From boating, to snowmobiling, to skiing, to motorcycling, to horse riding, this is a family of athletes, and they do it all together. So having Jadyn in college, leaves a big hole in the family dynamic, and they are all feeling it. The good news is that summer is coming, and Jadyn’s break from college.

Amanda and Sean decided to buy his parents cabin at Ryan Park, and the area is just beautiful. Ryan Park is in the Snowy Range, and the area is surrounded by trees and nature. They spent last Christmas up there. Everyone who joined them had a wonderful time. The cabin will be a wonderful addition to their many outdoor activities, both for summer and winter use. A cabin in the mountains is always a beautiful spot to spend time. I know they will really enjoy their time there.

Amanda has been working in the banking industry for all of her adult life, and she has made great strides in her field. Amanda went to work at the Rawlins National Bank at a young age and worked her way up to the pretty

prestigious position of BSA Agent, which is a part of the law enforcement area of the bank. Now, she has been promoted to Vice President over operations, which is a wonderful step up. She’s very happy about that! Amanda has worked so hard to advance her career, and she has been so successful in everything she does. This latest promotion is such a big one for her, and we are all so proud of this accomplishment. I know that the future will continue to be amazing for Amanda. It seems that every time she turns around, there is another great change waiting for her. She is such an engaging person, and always wears a smile. She has a great group of friends that, along with her family, round out her world very nicely. Today is Amanda’s birthday. Happy birthday Amanda!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

prestigious position of BSA Agent, which is a part of the law enforcement area of the bank. Now, she has been promoted to Vice President over operations, which is a wonderful step up. She’s very happy about that! Amanda has worked so hard to advance her career, and she has been so successful in everything she does. This latest promotion is such a big one for her, and we are all so proud of this accomplishment. I know that the future will continue to be amazing for Amanda. It seems that every time she turns around, there is another great change waiting for her. She is such an engaging person, and always wears a smile. She has a great group of friends that, along with her family, round out her world very nicely. Today is Amanda’s birthday. Happy birthday Amanda!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

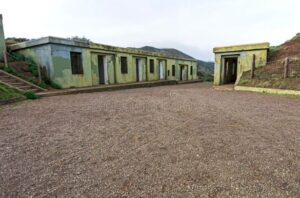

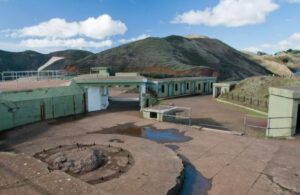

Battery Spencer was a reinforced concrete Endicott Period 12-inch gun battery, which was located on Fort Baker, Lime Point, Marin County, California. The structure still exists today and is a favorite tourist attraction. The battery was named on Feb 14, 1902, after Major General Joseph Spencer, who was a Revolutionary War hero. Spencer died on January 13, 1789. Construction on the battery began in 1893, and it was completed in 1897. Following its completion, it was transferred to the Coast Artillery for use on September 24, 1897, at a total cost of $110,352.70. It was deactivated in 1942 during World War II.

Battery Spencer was a reinforced concrete Endicott Period 12-inch gun battery, which was located on Fort Baker, Lime Point, Marin County, California. The structure still exists today and is a favorite tourist attraction. The battery was named on Feb 14, 1902, after Major General Joseph Spencer, who was a Revolutionary War hero. Spencer died on January 13, 1789. Construction on the battery began in 1893, and it was completed in 1897. Following its completion, it was transferred to the Coast Artillery for use on September 24, 1897, at a total cost of $110,352.70. It was deactivated in 1942 during World War II.

The battery was originally part of the Harbor Defense of San Francisco. The harbor was likely one of the most vulnerable entrances to San Fransisco, and in the early days of the country, when radar didn’t exist, it was hard to tell if an enemy was sneaking into the harbor, especially a submarine. Battery Spencer was a concrete coastal gun battery with three M1888 12-inch guns mounted on long range Barbette M1892 carriages. It was constructed on top of the five front emplacements of Battery Ridge. Back in the early 1900s, Battery Spencer was one of the main protection points for the San Francisco Bay. It featured multiple lookout points that were operated by the military and a few buildings for housing the generators and shells. It was used on and off until World War II when a lot of it was scrapped for war efforts.

The guns were mounted on 3 emplacements. Emplacements #1 and #2 were separated by a magazine with two shell rooms, a powder room, and a shell hoist room. Emplacement #3 had its own shell room, powder room, and hoist room. Spencer Battery was a two-story battery with the magazines on the lower level and the gun emplacements on the upper level. The missiles, or more likely cannon balls at first, were originally moved from the magazine level to the loading level with hand powered projectile hoists. In 1908, the hand powered hoists were replaced with electric Taylor-Raymond front delivery hoists. The new hoists were put into service on September 30, 1908. There were no powder hoists at Battery Spencer, meaning that gun powder had to be moved by hand.

Along the access road that runs north of Emplacement #1, was the BC Post and a separate building that had four rooms. The rooms consisted of a CO room, a guard room, an oil room, and a large 12′ by 43′ plotting room. All of these were used to plan any defensive action taken by the soldiers stationed at Battery Spencer. Two other buildings across the road completed the battery. One housed the tools and rammers, the other a latrine building with separate facilities for officers and enlisted. In 1910 the BC post and the plotting room were remodeled and updated. The work was accepted for service on August 5, 1910, at a cost of $1680.68.

When the United States entered World War I, it was decided that the large caliber coastal defense gun tubes should be removed from coastal batteries and sent into service in Europe. First, they were sent to arsenals for modification and mounting on mobile carriages, both wheeled and railroad. Strangely, most of the removed gun tubes never made it to Europe. Many were either remounted at the batteries or remained at the arsenals until needed elsewhere. One gun was removed from Battery Spencer emplacement #3 in 1918 and sent to Battery Chester at Fort Miley. The gun at Battery Spencer was never replaced, and the emplacement was considered abandoned. The carriage remained in place until it was ordered salvaged on January 10, 1927. World War II brought the first large scale scrap drive, and the remaining two guns and carriages were ordered scrapped on November 19, 1942.

These days Battery Spencer is part of the Golden Gate Recreation Area (GGNRA) administered by the National Park Service. It is a favorite historical attraction, even though no period guns or carriages are in place. The site is also one of the very best views of the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco.

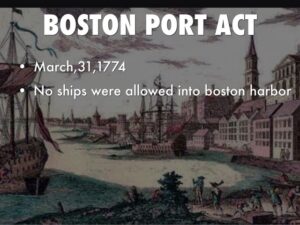

After the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, the tensions between the British Parliament and the American Colonies seethed for months. Then, on March 25, 1774, the British Parliament took the next step in its reign of tyranny, when it passed the Boston Port Act. The Boston Port Act closed the port of Boston to all incoming and outgoing ships, while demanding that the city’s residents pay for the nearly $1 million worth (in today’s money) of tea dumped into Boston Harbor during the Boston Tea Party. The act basically held the city under siege, while demanding a ransom for its release.

After the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, the tensions between the British Parliament and the American Colonies seethed for months. Then, on March 25, 1774, the British Parliament took the next step in its reign of tyranny, when it passed the Boston Port Act. The Boston Port Act closed the port of Boston to all incoming and outgoing ships, while demanding that the city’s residents pay for the nearly $1 million worth (in today’s money) of tea dumped into Boston Harbor during the Boston Tea Party. The act basically held the city under siege, while demanding a ransom for its release.

The Boston Port Act was the first and easiest to enforce of the four acts that resulted from the Boston Tea Party. Together, there were four acts, and they were known as the Coercive Acts. The other three were a new Quartering Act, the Administration of Justice Act, and the Massachusetts Government Act. These were passed as part of the Crown’s attempt to intimidate Boston’s increasingly unruly residents. King George III appointed General Thomas Gage, who commanded the British army in North America, as the new governor of Massachusetts in 1774, before the Massachusetts Government Act revoked the colony’s 1691 charter and curtailed the powers of the traditional town meeting and colonial council. Probably the biggest mistake the British made was in not understanding that the main reason the colonists left Britain was to get far enough away from Crown rule to live their own lives. These acts made it very clear to Bostonians that the crown intended to impose martial law, and that was something they just would not stand for.

Gage got right down to business, when in June, he easily sealed the ports of Boston and Charlestown using the formidable British navy. This act left merchants terrified of impending economic disaster. In their panic, many merchants simply wanted to pay for the tea and disband the Boston Committee of Correspondence, which had served to organize anti-British protests. Little did they know that to “bend their knees” to the tyranny would only have served to make matters worse. People make big mistakes when they get in fear. The merchants tried to convince their neighbors to appease the British in the hope of everything just “going away,” but that would never have been the case. A town meeting was called to discuss the matter, and the idea was immediately voted down by a substantial margin.

Parliament hoped that the Coercive Acts would isolate Boston from Massachusetts, Massachusetts from New England, and New England from the rest of North America, thereby preventing unified colonial resistance to the

British. Again, they misjudged the colonists, and their effort backfired. Rather than abandon Boston, the colonial population shipped much-needed supplies to Boston and formed extra-legal Provincial Congresses to mobilize resistance to the crown. By the time Gage attempted to enforce the Massachusetts Government Act, his authority had eroded beyond repair. It was another “shot to the heart” of the crown, that would ultimately lead to their complete downfall.

British. Again, they misjudged the colonists, and their effort backfired. Rather than abandon Boston, the colonial population shipped much-needed supplies to Boston and formed extra-legal Provincial Congresses to mobilize resistance to the crown. By the time Gage attempted to enforce the Massachusetts Government Act, his authority had eroded beyond repair. It was another “shot to the heart” of the crown, that would ultimately lead to their complete downfall.

Since moving from Powell, Wyoming to Butte, Montana has changed many things in my grandnephew, Weston Moore’s life. Weston is enjoying his life in Butte. He is working for a company that installs music sound systems in vehicle. This was a new line of work for Weston, and he is learning so much, and he can now figure out problems with electrical that we all dread on working on in vehicles!! He really enjoys the work, and his new life in Montana. Of course, with his family living so far away, he doesn’t get to see his parents, Steve and Machelle Moore and his brother, Easton Moore, as often as he used to. That makes it hard, and the weather in Montana and Wyoming doesn’t always make visiting home an easy thing to do.

Since moving from Powell, Wyoming to Butte, Montana has changed many things in my grandnephew, Weston Moore’s life. Weston is enjoying his life in Butte. He is working for a company that installs music sound systems in vehicle. This was a new line of work for Weston, and he is learning so much, and he can now figure out problems with electrical that we all dread on working on in vehicles!! He really enjoys the work, and his new life in Montana. Of course, with his family living so far away, he doesn’t get to see his parents, Steve and Machelle Moore and his brother, Easton Moore, as often as he used to. That makes it hard, and the weather in Montana and Wyoming doesn’t always make visiting home an easy thing to do.

Nevertheless, Weston managed to get home for his brother’s graduation, Thanksgiving, and Christmas this year. Weston loves to surprise his family. They ask him when he might be coming home, and he does his best to make them think it will be a long while…and then he shows up. Weston loves it when they are all surprised to see him. Weston’s family was hoping to go to Butte for his birthday, but unfortunately, this trip is going have to wait a little while, because the car needs new tires, and it gets better gas milage. It’s a struggle for a lot of people this year. Hopefully prices go down so they can get together and do more things this summer.

While all this has made for an interesting year, it’s Weston, himself that is the biggest news. Weston has been working for a while now to become…less!! Weston decided that he wanted to lose weight and get healthy, so he set out to do just that. I’m not sure how long he has been working on it, but I can tell you that 100 pounds doesn’t come off overnight. Losing that kind of weight takes hard work and determination. Weston had made up his mind, and he wasn’t quitting until he succeeded. We are all so proud of his success. He looks great, and

he decided that to complete his transformation, he needed a haircut too. Well, he succeeded in a complete transformation, and I can happily say that today, we have less Weston. Today is Weston’s 23rd birthday. Happy birthday Weston!! Have a great day!! We love you and we’re so proud of you!!

he decided that to complete his transformation, he needed a haircut too. Well, he succeeded in a complete transformation, and I can happily say that today, we have less Weston. Today is Weston’s 23rd birthday. Happy birthday Weston!! Have a great day!! We love you and we’re so proud of you!!

When this country was young, in fact, shortly before the Declaration of Independence was signed, and during a March 19, 1775, speech before the second Virginia Convention, Patrick Henry (39 years old) responded to the increasingly oppressive British rule over the American colonies by declaring, “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” The speech so impressed so many people that following the signing of the American Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, Patrick Henry was appointed governor of Virginia by the Continental Congress. He couldn’t have fully known with the future might bring, but I think he might have had an inkling of what an oppressive government could potentially do to a nation. His words were a warning, not only to his generation, but to generations to come.

When this country was young, in fact, shortly before the Declaration of Independence was signed, and during a March 19, 1775, speech before the second Virginia Convention, Patrick Henry (39 years old) responded to the increasingly oppressive British rule over the American colonies by declaring, “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” The speech so impressed so many people that following the signing of the American Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, Patrick Henry was appointed governor of Virginia by the Continental Congress. He couldn’t have fully known with the future might bring, but I think he might have had an inkling of what an oppressive government could potentially do to a nation. His words were a warning, not only to his generation, but to generations to come.

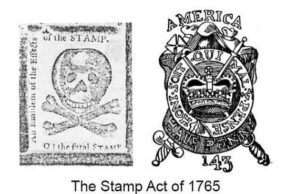

This young nation had been overtaxed, underrepresented, and in some ways enslaved, and they were done with it. The first major American opposition to British policy came in 1765 when Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which was a taxation measure to raise money for a standing British army in America. Basically, the Americans were being forced to pay for an army that was to keep them in line. That brought about the protest of “no taxation without representation,” and colonists convened the Stamp Act Congress in October 1765 to vocalize their opposition to the tax. With the enactment of the Stamp Act Congress on November 1, 1765, most colonists called for a boycott of British goods and organized attacks on the customhouses and homes of tax collectors. After months of protest, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766. Their plan had worked.

Even with the taxation of the Stamp Act, most colonists quietly accepted British rule, thinking that it was best not to cause trouble, but when Parliament enacted the Tea Act in 1773, which granted the East India Company a monopoly on the American tea trade, the American people had had enough. The Tea Act was viewed as another way to gouge the people with unfair taxation, militant Patriots in Massachusetts organized a protest that became known as the “Boston Tea Party,” at which, protesters dumped British tea valued at approximately 10,000 pounds into Boston Harbor. Of course, the “Boston Tea Party” and other blatant destruction of British property absolutely enraged Parliament. They enacted the Coercive Acts, also known as the Intolerable Acts, in the following year. The Coercive Acts closed Boston to merchant shipping, established formal British military rule in Massachusetts, made British officials immune to criminal prosecution in America, and required colonists to quarter British troops. The oppressive, tyrannical rule just continued to grow worse. The British thought that if they could keep the colonists “under their thumb,” as it were, they could basically make slave workers out of them, and gouge them for the monies to keep Britain running smoothly. The colonists had other ideas, and so they called the first Continental Congress to consider a united American resistance to the British…finally!!

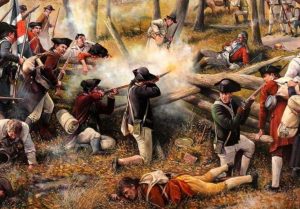

Massachusetts would lead the way of resistance against the British, with the other colonies watching intently. They formed a shadow revolutionary government and established militia groups to resist the increasing British military presence across the colony. Thomas Gage, the British governor of Massachusetts, ordered British

troops to march to Concord, Massachusetts in April 1775, where a Patriot arsenal was known to be located. On April 19, 1775, the British regulars encountered a group of American militiamen at Lexington, and the American Revolutionary War began. The fact was that Patrick Henry saw something that others did not see, that an out of control, oppressive government can be a terribly destructive force, if it is not held at bay.

troops to march to Concord, Massachusetts in April 1775, where a Patriot arsenal was known to be located. On April 19, 1775, the British regulars encountered a group of American militiamen at Lexington, and the American Revolutionary War began. The fact was that Patrick Henry saw something that others did not see, that an out of control, oppressive government can be a terribly destructive force, if it is not held at bay.

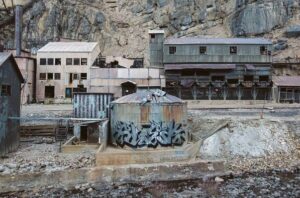

When corporate mining projects expanded and began to need a number of workers, the next logical step is to provide housing for the miners. By building a “company town” they could also control the rent, often making it necessary for the miners to spend all their wages, and even go into debt to get the things they needed to live. The “company town” of Gilman, Colorado was founded in 1886 during the Colorado Silver Boom, the town later became a center of lead and zinc mining in Colorado. The town was centered on the now-flooded Eagle Mine. When toxic pollutants, including contamination of the ground water in 1984, the town was abandoned by order of the Environmental Protection Agency. It was also due to unprofitability of the mines, meaning there was no longer a need for a “company town.”

When corporate mining projects expanded and began to need a number of workers, the next logical step is to provide housing for the miners. By building a “company town” they could also control the rent, often making it necessary for the miners to spend all their wages, and even go into debt to get the things they needed to live. The “company town” of Gilman, Colorado was founded in 1886 during the Colorado Silver Boom, the town later became a center of lead and zinc mining in Colorado. The town was centered on the now-flooded Eagle Mine. When toxic pollutants, including contamination of the ground water in 1984, the town was abandoned by order of the Environmental Protection Agency. It was also due to unprofitability of the mines, meaning there was no longer a need for a “company town.”

The town sat empty until 2007, when The Ginn Company began to make plans to build a private ski resort with private home sites across Battle Mountain, which would include development at the Gilman townsite. The Minturn Town Council, which held jurisdiction over Gilman, unanimously approved annexation and development  plans for 4,300 acres (6.7 square miles) of Ginn Resorts’ 1,700-unit Battle Mountain residential ski and golf resort, on February 27, 2008. Ginn’s Battle Mountain development would also include much of the old Gilman townsite. I’m not sure how I feel about that. To restore an old structure for a similar use is one thing, but to make it a ski resort seems wrong somehow. Then again, I guess as housing, it probably wouldn’t have been in the proper location to use as housing. On May 20, 2008, the town of Minturn approved the annexation in a public referendum with 87% of the vote. Then, as of September 9, 2009, the Ginn Company backed out of development plans for the Battle Mountain Property, so once again the site will be left to decay. Crave Real Estate Ventures, who was the original finance to Ginn, took over day to day operations of the property. For now, and the foreseeable future, Gilman is a ghost town on private property and is strictly off limits to the public.

plans for 4,300 acres (6.7 square miles) of Ginn Resorts’ 1,700-unit Battle Mountain residential ski and golf resort, on February 27, 2008. Ginn’s Battle Mountain development would also include much of the old Gilman townsite. I’m not sure how I feel about that. To restore an old structure for a similar use is one thing, but to make it a ski resort seems wrong somehow. Then again, I guess as housing, it probably wouldn’t have been in the proper location to use as housing. On May 20, 2008, the town of Minturn approved the annexation in a public referendum with 87% of the vote. Then, as of September 9, 2009, the Ginn Company backed out of development plans for the Battle Mountain Property, so once again the site will be left to decay. Crave Real Estate Ventures, who was the original finance to Ginn, took over day to day operations of the property. For now, and the foreseeable future, Gilman is a ghost town on private property and is strictly off limits to the public.

While it is illegal to go into the town, aerial views of it can still give an idea of what the town looked like. It makes me rather sad that people can’t go in and explore the old “company town” anymore, but I suppose they would need to decide it’s future before allowing the public to have access. Unfortunately, the public came be a  destructive force when it is turned loose on ruins. Right now, the townsite is a victim of vandalism, and the town’s main street is heavily tagged with graffiti. There are only a few intact windows left in town, as twenty years of vandalism have left almost every glass object in the town destroyed. Still, there are many parts of the town are almost as they were when the mine shut down. The main shaft elevators still sit ready for ore cars, permanently locked at the top level. Several cars and trucks still sit in their garages, left behind by their owners. Because of its size, modernity and level of preservation, the town is also the subject of interest for many historians, explorers, and photographers. I guess, “off limits to the public” doesn’t mean much.

destructive force when it is turned loose on ruins. Right now, the townsite is a victim of vandalism, and the town’s main street is heavily tagged with graffiti. There are only a few intact windows left in town, as twenty years of vandalism have left almost every glass object in the town destroyed. Still, there are many parts of the town are almost as they were when the mine shut down. The main shaft elevators still sit ready for ore cars, permanently locked at the top level. Several cars and trucks still sit in their garages, left behind by their owners. Because of its size, modernity and level of preservation, the town is also the subject of interest for many historians, explorers, and photographers. I guess, “off limits to the public” doesn’t mean much.

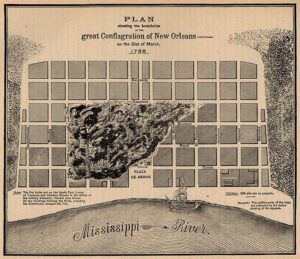

I don’t know what kind of a city New Orleans was in 1788, but much of it changed that year, because on March 21, 1788, the first of two great fires left the city in ruins. There are a number of ways to destroy a city…time, storms, neglect, need, and the worst one, fire. Were it not for two great fires, there might be more of colonial New Orleans left for people to enjoy. Unfortunately, two great fires in the late eighteenth century left New Orleans and its inhabitants very few years to re-establish their institutions before the onset of American domination in 1803, making the city more American than French. Today, there are several fine houses that date to the last colonial decade, as well as the French Quarter, including the Cabildo and the Presbytere, but they are “post-fire” nevertheless.

I don’t know what kind of a city New Orleans was in 1788, but much of it changed that year, because on March 21, 1788, the first of two great fires left the city in ruins. There are a number of ways to destroy a city…time, storms, neglect, need, and the worst one, fire. Were it not for two great fires, there might be more of colonial New Orleans left for people to enjoy. Unfortunately, two great fires in the late eighteenth century left New Orleans and its inhabitants very few years to re-establish their institutions before the onset of American domination in 1803, making the city more American than French. Today, there are several fine houses that date to the last colonial decade, as well as the French Quarter, including the Cabildo and the Presbytere, but they are “post-fire” nevertheless.

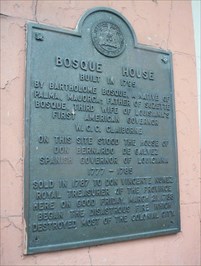

The French Quarter of today is very different from what it once was, and it makes me wonder what it might have been like before. These days, the French Quarter receives millions of visitors annually, and it’s hard to imagine the carnage of the fire of Holy Saturday morning in 1788. The fire was devastating, with smoking ruins stretching from Chartres to Dauphine Street, and from Conti to Saint Philip. The fire actually began on Good Friday morning in the home of Spanish treasurer Don Vincente Nunez at Toulouse and Chartres. The wind was blowing out of the southeast bringing in a blustery cold front. The wind, combined with the fire, reduced over eight hundred homes and public buildings to ashes in a matter of hours. The church, the town hall, and the rectory on the Plaza de Armas were suddenly gone. Governor Esteban Miro told Spanish authorities of the “abject misery, crying, and sobbing” of the people. He wrote that the faces of the families, “told the ruin of a city which in less than five hours has been transformed into an arid and horrible wilderness; the work of seventy years since its foundation.”

The rebuilding of the city began right away, but had barely started when, in 1794 a second fire and two hurricanes swept the city. It seemed that New Orleans was doomed to devastation. The December 8, 1794, fire burned 212 buildings…fewer than the prior fire, but these buildings were more valuable. After the two storms and both fires were done, nearly all the public buildings, homes and businesses, except those fronting the river had been reduced to ashes or badly damaged. Through it all the Ursuline nuns in their convent on Chartres Street had prayed over their hometown, and as the fire got close to the convent on that Good Friday, the wind suddenly shifted. Miraculously, the convent survived and still stands today.

The French Quarter was essentially changed forever. “Baked tile and quarried slate replaced the roofs of ax-hewn cypress shingles. Buildings, set at the sidewalk or banquette, were of all brick, with common firewalls. The wide and shallow hipped roof, galleried townhouse perfected in the French period gave way to vertical, long and narrow Spanish-style town homes, many with overhangs, iron work and entresols or mezzanines. The Cabildo and Presbytere came into being. A new church rose from the ashes. A suburb opened on the upper side of town for residents wary of crowded Quarter conditions. Fire pumps were commissioned. The market moved riverside. Artisans were called in. Protestants gained a foothold. But people went homeless, the city indebted, and lives were lost to death or removal. The city was different.”

Since 1794, the French Quarter has been spared large fires, although there have been some smaller fires, and the hurricanes kept coming. They are just common to the area. A great storm that took place on August 19, 1812, swept away a one-year-old French Market building. Another in 1915 damaged the steeple of Saint Louis Cathedral. A fire in September 1816 took the popular Orleans Theater and Orleans Ballroom. Then, the rebuilt theater burned again in 1866. Fire damaged the Bank of Louisiana on Royal Street resulting in the monumental columns installed in the remodeling, which is now the home of the Vieux Carré Commission.

These devastating losses have resulted in a stringent French Quarter fire code. No longer is the Mardi Gras

parade allowed to be motorized. The city takes prevention very seriously, knowing that fire spreading would be devastating to the French Quarter and to the city as a whole. Even with every precaution, the most important fires of the Twentieth Century occurred at individual structures. It is thought, by some historians, that the burning of the Old French Opera House on Bourbon, in 1919, was the “final nail” in the coffin of the old Creole culture in the Quarter, while others adopted that culture, thereby keeping its memory alive. Then, when the Cabildo burned in 1988, two hundred years after the First Great Fire, the citizens of the city felt the loss deeply. The structure was carefully restored, and it stands as a proud reminder of a city’s resolve to safeguard its heritage to this day.

parade allowed to be motorized. The city takes prevention very seriously, knowing that fire spreading would be devastating to the French Quarter and to the city as a whole. Even with every precaution, the most important fires of the Twentieth Century occurred at individual structures. It is thought, by some historians, that the burning of the Old French Opera House on Bourbon, in 1919, was the “final nail” in the coffin of the old Creole culture in the Quarter, while others adopted that culture, thereby keeping its memory alive. Then, when the Cabildo burned in 1988, two hundred years after the First Great Fire, the citizens of the city felt the loss deeply. The structure was carefully restored, and it stands as a proud reminder of a city’s resolve to safeguard its heritage to this day.

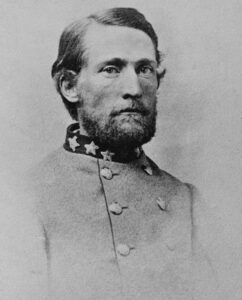

John Singleton Mosby was a Confederate army cavalry battalion commander in the American Civil War. He was also known as “The Gray Ghost.” Mosby’s command, the 43rd Battalion of the Virginia Cavalry was known as Mosby’s Rangers or Mosby’s Raiders. The Unit was a partisan ranger unit noted for its lightning-quick raids and its ability to elude Union Army pursuers and disappear, blending in with local farmers and townsmen. They were so quick and so skilled, that they practically vanished into thin air. Mosby was a legend, and the area of northern central Virginia soon became known as Mosby’s Confederacy. When the war was over, Mosby went on to become a Republican and worked as an attorney, supporting his former enemy’s commander, US President Ulysses S Grant. His political career took him to the US Department of Justice, where he served as the American consul to Hong Kong.

John Singleton Mosby was a Confederate army cavalry battalion commander in the American Civil War. He was also known as “The Gray Ghost.” Mosby’s command, the 43rd Battalion of the Virginia Cavalry was known as Mosby’s Rangers or Mosby’s Raiders. The Unit was a partisan ranger unit noted for its lightning-quick raids and its ability to elude Union Army pursuers and disappear, blending in with local farmers and townsmen. They were so quick and so skilled, that they practically vanished into thin air. Mosby was a legend, and the area of northern central Virginia soon became known as Mosby’s Confederacy. When the war was over, Mosby went on to become a Republican and worked as an attorney, supporting his former enemy’s commander, US President Ulysses S Grant. His political career took him to the US Department of Justice, where he served as the American consul to Hong Kong.

Mosby was born to Virginia McLaurine Mosby and Alfred Daniel Mosby in Powhatan County, Virginia, on December 6, 1833. He was a graduate of Hampden–Sydney College. Mosby’s father was a member of an old Virginia family of English origin whose ancestor, Richard Mosby,  was born in England in 1600. The family settled in Charles City, Virginia in the early 17th century. Young Mosby was named after his maternal grandfather, John Singleton, who was ethnically Irish.

was born in England in 1600. The family settled in Charles City, Virginia in the early 17th century. Young Mosby was named after his maternal grandfather, John Singleton, who was ethnically Irish.

While Mosby was a hero in some ways and a politician, there was another side of him too. Mosby was a Confederate battalion commander, yes, but he was known for his guerrilla military tactics. One of his biggest victories of the war found him and 29 of his men infiltrating the area surrounding the Fairfax County Courthouse in the middle of the night. They caught the Union officers completely off-guard, because they were 10 miles safe behind Union lines. The situation gave Mosby the opportunity he needed. He had captured a general, 30 other Union soldiers, and nearly 60 horses, which was already an incredibly valuable take during the war. In addition, Mosby decided to treat himself, and maybe or maybe not his men, to many of the Union men’s valuables, gathering quite a treasure for himself.

While they were taking their prisoners into Confederate territory, they were informed about Union troops in the area. Mosby decided that he needed to protect his goods. So, he left the group and buried his treasure between two trees. He marked the spot with an X. As sometimes happened, Mosby switched sides politically, and personally, after the war. He chose to support Lincoln and even went on to serve on President Grant’s administration. So, what of the treasure? Well, apparently Mosby never retrieved the treasure he pillaged. Some people reported that he sent Confederate soldiers to dig it up, but they were caught and killed by Union soldiers. And if that was the case, either they hadn’t started digging yet, or hadn’t made it to the location yet, because to this day, the treasure has never been found. I guess he took the location to his grave. John S Mosby died of complications after throat surgery in a Washington, DC hospital on May 30, 1916, noting at the end that it was Memorial Day. He is buried at the Warrenton Cemetery in Warrenton, Virginia.