Caryn

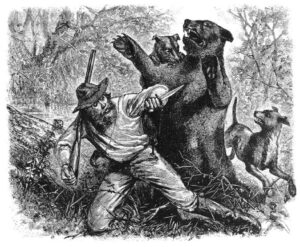

Being in the fur trade, especially back in the 1800s was no picnic. While the trapper was the one with the traps and the guns, that doesn’t mean that the wild animals couldn’t get the better of them from time to time. In addition, the hardships endured by even the most resilient of trappers, such as being alone in the wilderness and in constant danger of conflict with both wild animals and men, are beyond our ability to comprehend. Most perished in the quiet of remote areas, their names now lost, the valor of their final struggles unrecorded. Only the archives of the major fur companies offer scant references to such events deemed significant enough to document.

Being in the fur trade, especially back in the 1800s was no picnic. While the trapper was the one with the traps and the guns, that doesn’t mean that the wild animals couldn’t get the better of them from time to time. In addition, the hardships endured by even the most resilient of trappers, such as being alone in the wilderness and in constant danger of conflict with both wild animals and men, are beyond our ability to comprehend. Most perished in the quiet of remote areas, their names now lost, the valor of their final struggles unrecorded. Only the archives of the major fur companies offer scant references to such events deemed significant enough to document.

These events typically took place in the great mountains, where trappers held rendezvous and spent the majority of their lives. The catastrophic Battle of Pierre’s Hole, the valiant exploration of Utah, and the initial advance into California are all laden with dramatic episodes. However, these incidents occurred too far to the west to be included in the scope of this current work.

In the initial years of exploration, with beaver trapping along the streams, the Great Plains served primarily as a thoroughfare from civilized regions to the more lucrative mountainous areas beyond. Travelers, whether alone or in groups, journeyed up the Missouri River by boat or trekked along the Platte River valley on foot, aiming for the distant mountain ranges. Undoubtedly, they experienced considerable hardship, adventure, and conflicts with Native Americans along those extensive prairie stretches, yet these events were deemed too mundane to merit inclusion in the fur companies’ matter-of-fact records.

One man had a harrowing experience, and somehow it was deemed important to make it into the annals of history. The remarkable survival of Hugh Glass is a testament to the resilience and fortitude of these frontiersmen. Glass was part of Andrew Henry’s group on an expedition to the Yellowstone River. While hunting near the Grand River, a grizzly bear charged from the brush, knocked him down, ripped a chunk of flesh from him, and fed it to her cubs. Glass attempted to flee, but the bear quickly attacked again, biting his shoulder and causing severe injuries to his hands and arms. At that moment, his fellow hunters arrived and killed the bear. Glass was grievously injured and barely alive. He was not expected to live. In the hostile territory of the Native Americans, the group had to move on swiftly. Eventually, Major Henry persuaded two men to stay with Glass by offering a reward, while the rest continued on. The two were John S Fitzgerald and a man named “Bridges,” who some say was a young James “Jim” Bridger, the same Jim Bridger who would become a renowned trapper. That has not been confirmed. They stayed with Glass for five days, but losing hope in his recovery and seeing no signs of imminent death, they departed, taking his rifle and gear. Upon rejoining their group, they reported Glass as deceased.

Yet, Glass was still alive. Regaining consciousness, he dragged himself to a nearby spring. There, he found wild cherries and buffalo berries, which sustained him as he gradually regained his strength. Eventually, he embarked on a solitary trek to his destination, Fort Kiowa, on the Missouri River, 100 miles distant. He began his journey with barely enough strength to move, without provisions or any means to obtain them, in a land where any wandering Indian could easily overpower him. However, his will to live and a burgeoning desire for vengeance against those who had abandoned him spurred him on. Luck appeared to be on his side. He stumbled upon wolves attacking a buffalo calf. After the wolves had killed it, he scared them off and took the meat, consuming it as best as he could without a knife or fire. Carrying as much as possible, he continued determinedly and, despite immense suffering and difficulties, ultimately arrived at Fort Kiowa, located in what is now South Dakota.

Glass returned to the field before his wounds had fully healed. Heading east with a group of trappers along the Missouri River, they approached the Mandan villages, and he chose to traverse a bend in the river on foot. That turned out to be a wise move when Arikara Indians attacked the boats, killing everyone aboard. Glass, who was too weak to fight, narrowly escaped and was rescued by friendly Mandan Indians who took him to Tilton’s Fort. Driven by a desire for revenge against the two who had abandoned him in the mountains, he left Tilton’s that very night. So, Glass set out, braving the wilderness alone. He traveled for 38 days through territory hostile with Indian tribes, until he arrived at Fort Henry near the confluence of the Big Horn River in what is now Montana. There, he learned that the men he was after had headed east. Undeterred, he seized an opportunity to deliver a dispatch to Fort Atkinson, Nebraska.

Then, after completely healing from his injuries, Glass resumed his quest to locate Fitzgerald and “Bridges.” He made his way to Fort Henry on the Yellowstone River, only to discover it abandoned. A left-behind note revealed that Andrew Henry and his group had moved to a new encampment at the Bighorn River’s mouth. Upon reaching this location, Glass encountered “Bridges” and seemingly pardoned him due to his young age, before rejoining Ashley’s company.

Glass eventually discovered that Fitzgerald had enlisted in the army and was posted at Fort Atkinson, now in Nebraska. Glass chose to spare Fitzgerald’s life, knowing that the army captain would execute him for murdering a fellow soldier. Nevertheless, the captain demanded Fitzgerald return the rifle he had taken from Glass. Upon returning it, Glass cautioned Fitzgerald to never desert the army, or he would face death at Glass’s hands. A later account by Glass’s companion, George C Yount, which wasn’t published until 1923, revealed that Glass received $300 in restitution. I’m sure Fitzgerald felt he got off easy and had no plans to leave the army.

In early 1833, Glass, along with fellow trappers Edward Rose and Hilain Menard, was killed on the Yellowstone River during an Arikara attack. A monument honoring Glass stands near the location of his mauling on the southern bank of what is now Shadehill Reservoir in Perkins County, South Dakota, at the confluence of the Grand River. The adjacent Hugh Glass Lakeside Use Area also offers a state-maintained campground and picnic site at no cost.

In early 1833, Glass, along with fellow trappers Edward Rose and Hilain Menard, was killed on the Yellowstone River during an Arikara attack. A monument honoring Glass stands near the location of his mauling on the southern bank of what is now Shadehill Reservoir in Perkins County, South Dakota, at the confluence of the Grand River. The adjacent Hugh Glass Lakeside Use Area also offers a state-maintained campground and picnic site at no cost.

When my Aunt Sandy Pattan and I go to lunch, she will usually forego vegetables for a double portion of mashed potatoes. Her request will usually accompany her asking me if I know that she is Irish, and so the love of potatoes. Of course, I know that she is Irish, because she is my aunt, and I know about my own Irish ties through her side of the family. Nevertheless, I can’t say that I connected the Irish part with potatoes. So, I decided to do a little research to find our why “the Irish like potatoes” as my aunt says. In my research, I found probably the last thing I expected.

When my Aunt Sandy Pattan and I go to lunch, she will usually forego vegetables for a double portion of mashed potatoes. Her request will usually accompany her asking me if I know that she is Irish, and so the love of potatoes. Of course, I know that she is Irish, because she is my aunt, and I know about my own Irish ties through her side of the family. Nevertheless, I can’t say that I connected the Irish part with potatoes. So, I decided to do a little research to find our why “the Irish like potatoes” as my aunt says. In my research, I found probably the last thing I expected.

In the annals of Irish history, the potato transcends its role as a staple food; it embodies both prosperity and hardship. It was instrumental in supporting the population during times of expansion, yet it also played a pivotal role in one of Ireland’s most catastrophic episodes: the Great Famine. The story of the potato in Ireland  is a tale of how a single crop can influence the fate of a nation, weaving itself into the very fabric of the Irish cultural identity.

is a tale of how a single crop can influence the fate of a nation, weaving itself into the very fabric of the Irish cultural identity.

Few events in Irish history are as dark and devastating as the Great Hunger, also known as the Potato Famine. At that time, Ireland was a colony of Great Britain, which relied heavily on the country for potato production. However, in 1845, a devastating disease destroyed 75% of the potato crop, persisting for over five years. The local Irish population suffered the most. Estimates suggest that approximately one million Irish people died of starvation during the famine and another million emigrated. By the end of the famine in 1852, Ireland’s population had decreased by 25%. The British government faced criticism for its inadequate response, and the catastrophe fueled the drive for Irish independence. The Irish people felt that the British had not tried hard enough to take care of the people under their rule.

As often happens when a food item is no longer allowed or readily available, the Irish people loved their potatoes. The significance of the potato in Irish culture surpasses its agricultural importance, profoundly influencing culinary customs. It turned into a dietary mainstay, with creations like colcannon (mashed potatoes with kale or cabbage), boxty (potato pancakes) being a beloved dish in my Grandma Byer’s (Aunt Sandy’s mom) home, and Irish stew (potatoes, meat, and vegetables) becoming indispensable. These dishes were not

merely nourishing but also reflected the creativity and adaptability of Irish cooks who produced a variety of meals from a few ingredients. The simple yet hearty character of these potato-centric dishes mirrored the lives and struggles of ordinary people, ingraining these recipes in the heart of Irish cooking traditions. And with that, I feel like I now understand my aunt’s obsession with potatoes.

merely nourishing but also reflected the creativity and adaptability of Irish cooks who produced a variety of meals from a few ingredients. The simple yet hearty character of these potato-centric dishes mirrored the lives and struggles of ordinary people, ingraining these recipes in the heart of Irish cooking traditions. And with that, I feel like I now understand my aunt’s obsession with potatoes.

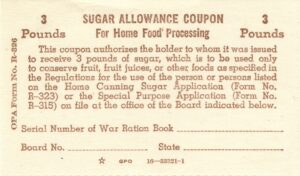

War usually brings with it, shortages and rationing. On November 29, 1942, coffee was added to the list of rationed items in the United States. Now, people can live without some things, but I would think that coffee would be a really hard item to add to that list. The coffee production in Latin America was at a record, but it made no difference, the increasing demand from military and civilian sectors, along with the pressing needs of shipping for other wartime efforts, necessitated the restriction of its availability.

War usually brings with it, shortages and rationing. On November 29, 1942, coffee was added to the list of rationed items in the United States. Now, people can live without some things, but I would think that coffee would be a really hard item to add to that list. The coffee production in Latin America was at a record, but it made no difference, the increasing demand from military and civilian sectors, along with the pressing needs of shipping for other wartime efforts, necessitated the restriction of its availability.

The truth is that scarcity or shortages were seldom the cause of rationing during the war. Rationing was typically implemented for two main reasons…to ensure an equitable distribution of resources and food to all citizens and to prioritize military needs for certain raw materials in light of the current emergency.

At first, the restriction on the use of certain items was voluntary. People were simply asked to cut back. The problem is that voluntary cutting back seldom works. Also, President Roosevelt initiated “scrap drives” to collect discarded rubber items like old garden hoses, tires, and bathing caps, especially after Japan seized the Dutch East Indies, a key rubber supplier for the United States. These collected items could be exchanged at gas stations for a penny per pound. In the early stages of the war, patriotism and the eagerness to support the war effort was enough.

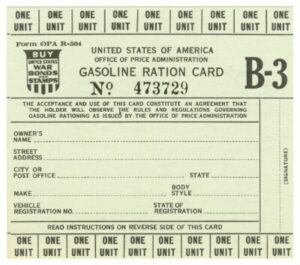

As US shipping, including oil tankers, became increasingly susceptible to German U-boat attacks, gasoline was the first commodity to be rationed. In seventeen eastern states, car owners were limited to three gallons of gasoline weekly beginning in May 1942. By year’s end, rationing had expanded nationwide, with drivers required to affix ration stamps to their car windshields. Things like butter, were reserved for military use, and so were also rationed. Also limited were coffee, sugar, and milk. In fact, approximately one-third of all food typically consumed by civilians was rationed during the war at some point. We had to make sure our troops had what they needed. They were fighting for our freedom, and we would sacrifice so they could have

what they needed. The American people were determined and willing. Of course, that didn’t stop the black market from becoming a source for rationed items, selling goods at prices above those set by the Office of Price Administration to Americans who could afford the marked-up costs. Nevertheless, certain items were removed from the rationing list ahead of time; coffee became available in July 1943, but sugar remained rationed until June 1947.

what they needed. The American people were determined and willing. Of course, that didn’t stop the black market from becoming a source for rationed items, selling goods at prices above those set by the Office of Price Administration to Americans who could afford the marked-up costs. Nevertheless, certain items were removed from the rationing list ahead of time; coffee became available in July 1943, but sugar remained rationed until June 1947.

Thanksgiving Day is a time-honored tradition where we reflect on our lives and express gratitude for the blessings we’ve received throughout the year and in years gone by. We take inventory of all the aspects of our lives. The sorrowful aspects are momentarily put aside for another time, allowing us to concentrate on our family, friends, and homes. We also look forward to the future and its potential blessings. It’s not merely about material possessions; in fact, such things often take a backseat in our thoughts. Our attention is much more on the people we love. My family has been blessed with a number of new babies this year, and babies are always one of our best reasons to be thankful. We received a wonderful miracle, as the lives of two of our nephews were spared in a car fire. They have recovered well and are back with their family. While Thanksgiving is not the only occasion for appreciating our loved ones, it’s a perfect reminder to give thanks for everyday blessings that we might normally overlook in our daily lives.

Thanksgiving Day is a time-honored tradition where we reflect on our lives and express gratitude for the blessings we’ve received throughout the year and in years gone by. We take inventory of all the aspects of our lives. The sorrowful aspects are momentarily put aside for another time, allowing us to concentrate on our family, friends, and homes. We also look forward to the future and its potential blessings. It’s not merely about material possessions; in fact, such things often take a backseat in our thoughts. Our attention is much more on the people we love. My family has been blessed with a number of new babies this year, and babies are always one of our best reasons to be thankful. We received a wonderful miracle, as the lives of two of our nephews were spared in a car fire. They have recovered well and are back with their family. While Thanksgiving is not the only occasion for appreciating our loved ones, it’s a perfect reminder to give thanks for everyday blessings that we might normally overlook in our daily lives.

This has been a hard year for some people, including my Aunt Sandy, but the Lord has blessed her, and she has come through so many life-threatening events that it is impossible not to feel a great deal of thankfulness. Today, Aunt Sandy is stronger and healthier than ever, and she even has perfect vision, because she had cataract surgery this year. Instead of ending up in a nursing home because she was too weak to live on her own, Aunt Sandy is living on her own and thriving. She is even doing puzzles, taking care of her own home (beautifully, I might add), and doing some crafting. Today is a great day of celebration for Aunt Sandy and her family.

This has been a hard year for some people, including my Aunt Sandy, but the Lord has blessed her, and she has come through so many life-threatening events that it is impossible not to feel a great deal of thankfulness. Today, Aunt Sandy is stronger and healthier than ever, and she even has perfect vision, because she had cataract surgery this year. Instead of ending up in a nursing home because she was too weak to live on her own, Aunt Sandy is living on her own and thriving. She is even doing puzzles, taking care of her own home (beautifully, I might add), and doing some crafting. Today is a great day of celebration for Aunt Sandy and her family.

I believe most people are grateful for their blessings, yet there’s a distinction between feeling grateful and expressing gratitude. That difference lies in recognizing the source of those blessings—God. I imagine those who don’t believe in God might not feel compelled to thank Him, but my deep faith tells me that my blessings can only come from Him. God’s love is abundant, and it is He who bestows His blessings upon me. On this Thanksgiving Day, it is to Him, the Almighty God, that I offer my thanks. Like many, I might overlook the importance of thanking God as I should, but perhaps a National Day of Thanksgiving

provides us all a chance to pause from our hectic lives to appreciate our fortunes. On this day, let us take a moment to acknowledge God’s grace and mercy towards us and to thank Him for all He has done for us. Wishing everyone a Happy Thanksgiving, and I extend my gratitude to God for His boundless love and the blessings bestowed upon me and my family, and upon my Aunt Sandy too.

provides us all a chance to pause from our hectic lives to appreciate our fortunes. On this day, let us take a moment to acknowledge God’s grace and mercy towards us and to thank Him for all He has done for us. Wishing everyone a Happy Thanksgiving, and I extend my gratitude to God for His boundless love and the blessings bestowed upon me and my family, and upon my Aunt Sandy too.

My husband, Bob Schulenberg’s grandfather, Robert Knox was mostly a quiet man. Maybe that came from his years herding sheep. For me, thinking of Grandpa’s time as a shepherd, reminded me of Jesus as the good shepherd. This image doesn’t necessarily evoke memories of my husband’s grandfather, Robert Knox, for most of our family, but it does for me. Jesus always took care of his sheep, and Grandpa always took care of his sheep and his family too. A shepherd’s primary duty is to ward off predators like coyotes, mountain lions, bears, or any other threat that could harm or kill the sheep. Historically, and perhaps even now, the shepherd is often the sole guardian of the sheep, since sheep are known to be quite docile. Predators, on the other hand, are anything but docile. Driven by hunger, they see the shepherd as the only barrier between them and their prey, placing the shepherd directly in harm’s way. That could have been the position Grandpa found himself in.

My husband, Bob Schulenberg’s grandfather, Robert Knox was mostly a quiet man. Maybe that came from his years herding sheep. For me, thinking of Grandpa’s time as a shepherd, reminded me of Jesus as the good shepherd. This image doesn’t necessarily evoke memories of my husband’s grandfather, Robert Knox, for most of our family, but it does for me. Jesus always took care of his sheep, and Grandpa always took care of his sheep and his family too. A shepherd’s primary duty is to ward off predators like coyotes, mountain lions, bears, or any other threat that could harm or kill the sheep. Historically, and perhaps even now, the shepherd is often the sole guardian of the sheep, since sheep are known to be quite docile. Predators, on the other hand, are anything but docile. Driven by hunger, they see the shepherd as the only barrier between them and their prey, placing the shepherd directly in harm’s way. That could have been the position Grandpa found himself in.

You may be curious about the relevance to Grandpa Knox, and indeed, there is a connection. Grandpa Knox once worked as a shepherd, and he had a greater imperative to protect his flock from predators. Unlike many shepherds who were alone, Grandpa was not. Accompanied by his wife, Nettie, and their three-year-old daughter, Joann Knox (Schulenberg), his first duty was their safety. While I cannot confirm any encounters where he wrestled with coyotes, mountain lions, or bears, it is conceivable that he had to scare some away using a gun or maybe just a loud voice.

Grandpa Knox never seemed to be the type to hunt or confront predators, yet I imagine he would have risen to the occasion if needed. The Grandpa Knox I knew when I became part of the family was more inclined towards

gardening. He devoted many summer hours to cultivating the garden at my in-laws’ place, which blessed our family with an abundance of wonderful vegetables. I used to think the most formidable predator he faced was perhaps a stray cow or a ravenous rabbit. Indeed, he dealt with those as well, but there was a time when he safeguarded his sheep from predators, reminiscent of the biblical shepherd tales. Today marks the 116th anniversary of Grandpa Knox’s birth. Wishing you a happy Heavenly birthday, Grandpa Knox. We love and miss you very much.

gardening. He devoted many summer hours to cultivating the garden at my in-laws’ place, which blessed our family with an abundance of wonderful vegetables. I used to think the most formidable predator he faced was perhaps a stray cow or a ravenous rabbit. Indeed, he dealt with those as well, but there was a time when he safeguarded his sheep from predators, reminiscent of the biblical shepherd tales. Today marks the 116th anniversary of Grandpa Knox’s birth. Wishing you a happy Heavenly birthday, Grandpa Knox. We love and miss you very much.

Last Thursday brought the sad news that my aunt, Doris Spencer was leaving this earth. It was so hard to believe, mostly because she had lived her for a little over 100 years. So many people don’t get that opportunity, but Aunt Doris was very blessed. She had beaten the odds, to become a centenarian!! We were all so happy for her, and she was so happy. Her birthday celebration was such a wonderful event…worthy of her great accomplishment.

Last Thursday brought the sad news that my aunt, Doris Spencer was leaving this earth. It was so hard to believe, mostly because she had lived her for a little over 100 years. So many people don’t get that opportunity, but Aunt Doris was very blessed. She had beaten the odds, to become a centenarian!! We were all so happy for her, and she was so happy. Her birthday celebration was such a wonderful event…worthy of her great accomplishment.

The reality is that her whole life was lived as a blessing. I will never forget when we visited her. She always made everything so special. It didn’t matter what time we arrived; she would get up and make a meal. She always felt that a guest should have something to eat, and she was a wonderful cook, so we didn’t argue with her philosophy. We had so many wonderful visits through the years. I specifically remember the time we got to go and pick blueberries. Then we had cereal with fresh blueberries on it. Oh, my goodness!! So good!!

Aunt Doris’ life was blessed with children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren. Her family was the most important part of her life. She was blessed with long life and good health. For most of her years, she was able to get around largely on her own, even when she no longer drove, she could still maneuver and visit with family and friends. Aunt Doris liked people, and she enjoyed being with people. Now her life wasn’t perfect, and she has lost loved ones, but she knew she would see those who went before her, again, and now she is in Heaven with those who have gone before her.

Aunt Doris was the saving grace for my mother. When my mom, Collene Spencer and dad, Al Spencer got married and moved to Superior, Wisconsin, Aunt Doris and Uncle Bill rented the house behind their own to my

parents. The girls became best friends, and mom, who had never been away from her family before, felt like it would all be ok. She and Aunt Doris had so many “escapades” together, and they wouldn’t have traded a single one for anything different. Now, the girls are back together again in Heaven, and I’m sure they are having a wonderful time. I’m sure Aunt Doris is having a great time with all of her family and friends who have gone before her. We will miss Aunt Doris so much. She lived a wonderful, long life, and she was a blessing to all of us. Aunt Doris, we love you so much, and we can’t wait to see you again.

parents. The girls became best friends, and mom, who had never been away from her family before, felt like it would all be ok. She and Aunt Doris had so many “escapades” together, and they wouldn’t have traded a single one for anything different. Now, the girls are back together again in Heaven, and I’m sure they are having a wonderful time. I’m sure Aunt Doris is having a great time with all of her family and friends who have gone before her. We will miss Aunt Doris so much. She lived a wonderful, long life, and she was a blessing to all of us. Aunt Doris, we love you so much, and we can’t wait to see you again.

When we see a structure like the Pontcysyllte Aquaduct in northeast Wales, we usually assume that it is simply a bridge or a railroad trestle, but in this case, we are very wrong. While the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct is navigable, it actually carries the Llangollen Canal across the River Dee in the Vale of Llangollen. I wondered why they needed an aqueduct to carry one river over another, but the truth is that the smaller river would be swallowed up by the larger, ending any possibility of the smaller river reaching the intended destination. The 18-arched stone and cast-iron aqueduct is designed for narrowboats and was completed in 1805 after a decade of planning and construction. Measuring 12 feet in width, it stands as the longest aqueduct in Great Britain and the tallest canal aqueduct in the world.

When we see a structure like the Pontcysyllte Aquaduct in northeast Wales, we usually assume that it is simply a bridge or a railroad trestle, but in this case, we are very wrong. While the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct is navigable, it actually carries the Llangollen Canal across the River Dee in the Vale of Llangollen. I wondered why they needed an aqueduct to carry one river over another, but the truth is that the smaller river would be swallowed up by the larger, ending any possibility of the smaller river reaching the intended destination. The 18-arched stone and cast-iron aqueduct is designed for narrowboats and was completed in 1805 after a decade of planning and construction. Measuring 12 feet in width, it stands as the longest aqueduct in Great Britain and the tallest canal aqueduct in the world.

Alongside the watercourse, there is a towpath on one side. “A towpath is a road or trail on the bank of a river, canal, or other inland waterway. The purpose of a towpath is to allow a land vehicle, beasts of burden, or a team of human pullers to tow a boat, often a barge. This mode of transport was common where sailing was impractical because of tunnels and bridges, unfavorable winds, or the narrowness of the channel.”

The Pontcysyllte Aqueduct was intended to be a central feature of the Ellesmere Canal, a proposed industrial waterway linking the River Severn at Shrewsbury with the Port of Liverpool on the River Mersey. Despite a cheaper route surveyed to the east, the chosen path traversed the Vale of Llangollen’s high ground to the west, passing through Northeast Wales’ coal-rich areas. The canal was only partially completed due to insufficient revenue generation for the entire project. Following the aqueduct’s partial completion in 1805, most significant construction stopped.

The aqueduct, designed by civil engineers Thomas Telford and William Jessop, was intended for a site near the 18th-century road crossing at Pont Cysyllte. Following the approval of the westerly high-ground route, the initial plan involved constructing a series of locks along both valley sides leading to an embankment that would  carry the Ellesmere Canal over the River Dee. However, once Telford joined the project, the design shifted to an aqueduct that would provide a direct and continuous waterway across the valley. Despite widespread public doubt, Telford remained confident in his construction approach, drawing on his experience from building the Longdon-on-Tern Aqueduct, a cast-iron trough aqueduct on the Shrewsbury Canal.

carry the Ellesmere Canal over the River Dee. However, once Telford joined the project, the design shifted to an aqueduct that would provide a direct and continuous waterway across the valley. Despite widespread public doubt, Telford remained confident in his construction approach, drawing on his experience from building the Longdon-on-Tern Aqueduct, a cast-iron trough aqueduct on the Shrewsbury Canal.

The Pontcysyllte aqueduct officially opened to traffic on 26 November 1805. A plaque commemorating its inauguration reads, “The nobility and gentry, the adjacent Counties having united their efforts with the great commercial interests of this country. In creating an intercourse and union between England and North Wales by a navigable communication of the three Rivers, Severn, Dee and Mersey for the mutual benefit of agriculture and trades, caused the first stone of this aqueduct of Pontcysyllte, to be laid on the 25th day of July MDCCXCV [1795]. When Richard Myddelton of Chirk, Esq, MP one of the original patrons of the Ellesmere Canal was Lord of this manor, and in the reign of our Sovereign George the Third. When the equity of the laws, and the security of property, promoted the general welfare of the nation. While the arts and sciences flourished by his patronage and the conduct of civil life was improved by his example.”

The bridge measures 336 yards in length, 12 feet in width, and has a depth of 5 feet 3 inches. It features a cast iron trough, which is supported 126 feet above the river by iron arched ribs resting on eighteen hollow masonry piers. Each of the bridge’s 18 spans measures 53 feet across. Following the aqueduct’s completion, the canal was intended to extend to Moss Valley, Wrexham, where Telford had built a feeder reservoir lake in 1796 to supply water for the canal stretch from Trevor Basin to Chester. However, the plan to construct this section was abandoned in 1798, which lead to the neglect, and eventual abandonment, of the feeder and a navigable stretch between Ffrwd and a basin in Summerhill. Traces of the feeder channel can still be seen in Gwersyllt, and a street in the village bears the name Heol Camlas, meaning ‘canal way’ in Welsh. John Simpson of Shrewsbury, who died in 1815, oversaw the physical construction.

With the project incomplete, Trevor Basin, located just beyond the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, became the canal’s

northern terminus. By 1808, a feeder channel had been completed to transport water from the River Dee near Llangollen. To ensure a constant water supply, Telford constructed an artificial weir, known as the Horseshoe Falls, near Llantysilio to regulate the water level. The aqueduct is classified as a Grade I listed building and is a part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

northern terminus. By 1808, a feeder channel had been completed to transport water from the River Dee near Llangollen. To ensure a constant water supply, Telford constructed an artificial weir, known as the Horseshoe Falls, near Llantysilio to regulate the water level. The aqueduct is classified as a Grade I listed building and is a part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The HMT Rohna, originally known as SS Rohna, was a passenger and cargo liner belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company. Constructed in Tyneside in 1926, it was one of two new vessels ordered by the British India Line in 1925 for its Madras–Nagapatam–Singapore route. These sister ships had slight variations…being built at different shipyards with different engines. Hawthorn Leslie and Company constructed the Rohna in Hebburn on Tyneside, while Barclay, Curle and Company built the Rajula in Glasgow on Clydeside. The two ships were completed and launched around the same time in mid-1926.

The HMT Rohna, originally known as SS Rohna, was a passenger and cargo liner belonging to the British India Steam Navigation Company. Constructed in Tyneside in 1926, it was one of two new vessels ordered by the British India Line in 1925 for its Madras–Nagapatam–Singapore route. These sister ships had slight variations…being built at different shipyards with different engines. Hawthorn Leslie and Company constructed the Rohna in Hebburn on Tyneside, while Barclay, Curle and Company built the Rajula in Glasgow on Clydeside. The two ships were completed and launched around the same time in mid-1926.

The Rohna was launched on August 24, 1926, and her construction was completed by November 5. Named after a village in Sonipat, Punjab, India, she featured 15 corrugated furnaces heating five single-ended boilers, which together had a heating surface of 14,080 square feet. These boilers supplied steam at 215 lbf/in^2 (pounds per square inch) to two four-cylinder quadruple expansion steam engines, yielding a combined power of 984 Nominal Horsepower (NHP). Each engine propelled one of the ship’s twin screws, enabling the Rohna to achieve 984 NHP or 5,000 Indicated Horsepower (IHP). On her sea trials, she reached 14.3 knots (2, with a cruising speed of 12.5 knots). By 1934, the Rohna was equipped with wireless direction-finding equipment.

As the United Kingdom entered the World War II in September 1939, the Rohna was navigating the Indian Ocean. Other than a journey from Karachi to Suez with Convoy K 4, the Rohna sailed unescorted between Rangoon and Madras until the end of November. Departing Bombay on December 10th, she headed for the Mediterranean, transited the Suez Canal on December 20-21, and arrived in Marseille on December 26th. From January 3, 1940, to March 10th, she moved unescorted between Marseille and the Port of Haifa in Mandatory Palestine, initially as part of convoys but later, after January 29th, on her own.

On March 15, 1940, the Rohna sailed back through the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean, where she operated unescorted between Bombay, Rangoon, and Colombo until June. In May, she was requisitioned as a troop ship, and on June 6th, she departed from Bombay to Durban. She continued to operate between Durban, Mombasa, and Dar es Salaam until July 28th, when she embarked from Mombasa to return to Bombay.

The Rohna transported troops from Bombay to Suez in August 1940 with Convoy BN 3, and from Bombay to Port Sudan in September/October 1940 with Convoy BN 6. Subsequent journeys included Bombay to Suez in November 1940 with Convoy BN 8A, Colombo to Suez in February 1941 with Convoy US 8/1, and Bombay to Singapore in March 1941 with Convoy BM 4. Following the Iraqi coup d’état in April 1941, the Rohna was directed to Karachi, from where she transported early units of Iraqforce to Basra in Convoy BP 2. During the Anglo-Iraqi War in May, she completed a second voyage from Karachi to Basra with Convoy BP 5. After the Allied triumph in Iraq at May’s end, she continued shuttling between Basra and Bombay, departing to Basra with BP-series convoys and returning independently.

On December 8, 1941, Japan invaded Malaya. The following month, Rohna departed Bombay for Singapore with Convoy BM 10, arriving on January 25, 1942. She set sail on January 28 in Convoy NB 1, two weeks before Singapore fell to Japan. From March 1942, Rohna spent a year navigating the Indian Ocean, visiting Bombay, Karachi, Colombo, Basra, Aden, Suez, Khorramshahr, Bandar Abbas, Bahrain, and Abadan, sometimes as part of convoys, often unescorted. In March 1943, she embarked from Bombay with Convoy BA 40 to Aden, then proceeded independently to Suez, passing through the canal on April 6–7.

Throughout the rest of her service, Rohna was instrumental in supporting the North African Campaign, as well as the Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy. Until early July, she operated independently, navigating between Alexandria, Tripoli, and Sfax. She primarily joined convoys, plying the routes between Alexandria,

Malta, Tripoli, Augusta, Port Said, Bizerte, and Oran.

Malta, Tripoli, Augusta, Port Said, Bizerte, and Oran.

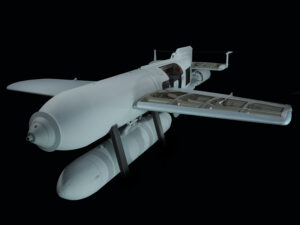

Her requisition as a troop carrier in 1940, at the onset of World War II, placed a target of sorts on her back, and in November 1943, the Rohna was sunk in the Mediterranean by a Henschel HS 293 guided glide bomb launched from a Luftwaffe aircraft. The attack resulted in the deaths of over 1,100 individuals, the majority being United States troops.

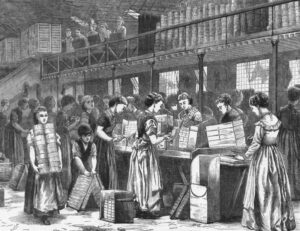

In 1887, Annie Besant and William Stead founded a newspaper that they called The Link. This halfpenny weekly featured on its front page a quote from Victor Hugo: “I will speak for the dumb. I will speak of the small to the great and the feeble to the strong… I will speak for all the despairing silent ones.” The newspaper campaigned against “sweated labour, extortionate landlords, unhealthy workshops, child labour and prostitution.” I’m sure these things made the owners hated among the labor bosses.

In 1887, Annie Besant and William Stead founded a newspaper that they called The Link. This halfpenny weekly featured on its front page a quote from Victor Hugo: “I will speak for the dumb. I will speak of the small to the great and the feeble to the strong… I will speak for all the despairing silent ones.” The newspaper campaigned against “sweated labour, extortionate landlords, unhealthy workshops, child labour and prostitution.” I’m sure these things made the owners hated among the labor bosses.

In June 1888, Clementina Black delivered a speech on Female Labour at a Fabian Society meeting in London. Annie Besant, who was in the audience, was appalled to learn about the wages and working conditions of the women at the Bryant and May match factory. Taking immediate action, Besant interviewed several employees of Bryant and May the very next day. She found out that the women labored for fourteen hours daily, earning less than five shillings per week. Their full wages were often reduced due to a fine system, which ranged from three pence to one shilling, enforced by the Bryant and May management for infractions such as talking, dropping matches, or using the restroom without permission. The workday started at 6:30am in summer (8:00am in winter) and ended at 6:00pm. Workers arriving late were penalized with a deduction of half a day’s wages.

Annie Besant found that the women’s health was drastically impacted by the phosphorus in the match-making process. It led to skin yellowing, hair loss, and “phossy jaw,” which is a type of bone cancer. The disease would turn one side of the face green, then black, emitting a foul odor before resulting in death. Despite phosphorus being outlawed in Sweden and the USA, the British government declined to enact a similar ban, citing free trade restrictions, and the health of the workers “be hanged.”

On June 23, 1888, Annie Besant published an article in her newspaper, The Link, titled “White Slavery in London,” which criticized the treatment of women at Bryant and May. The company responded by trying to coerce their workers into signing a declaration of satisfaction with their working conditions. When a group of  women refused to sign, the group’s organizers were dismissed. The reaction to the dismissals was swift…1,400 women at Bryant and May went on strike.

women refused to sign, the group’s organizers were dismissed. The reaction to the dismissals was swift…1,400 women at Bryant and May went on strike.

William Stead of the Pall Mall Gazette, Henry Hyde Champion from the Labour Elector, and Catharine Booth of the Salvation Army supported Besant’s campaign for improved factory working conditions. Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Sydney Oliver, Stewart Headlam, Hubert Bland, Graham Wallas, and George Bernard Shaw also joined the cause. Conversely, newspapers like The Times criticized Besant and other socialist leaders for the dispute, lamenting that “the matchgirls have been deprived of acting on their own but have been incited to strike by irresponsible advisors. No effort has been spared by these nuisances of the modern industrial world to escalate this conflict.”

Besant, Stead, and Champion leveraged their newspapers to advocate for a boycott of Bryant and May’s matches. Emmeline Pankhurst was among those who joined the strike. In her autobiography, she reflected, “I embraced this strike with zeal, collaborating with the girls and several distinguished women, including the renowned Mrs Annie Besant… It was a period marked by significant turmoil, labour disputes, strikes, and lockouts. It was also a time when an incredibly obtuse reactionary sentiment appeared to dominate the Government and the authorities.”

The women at the company decided to establish a Matchgirls’ Union, and Besant consented to lead it. Three weeks later, the company declared its willingness to rehire the dismissed women and abolish the fines system. The women agreed to these terms and returned triumphantly. The Bryant and May dispute became the first strike by unorganized workers to actually receive national attention and it successfully inspired the creation of unions nationwide.

Several years later, trade union leader Henry Snell reflected, “These brave girls, lacking funds, organization, or leaders, turned to Mrs Besant for guidance and leadership. It was an astute and superb inspiration. Although the number impacted was relatively small, the matchgirls’ strike profoundly influenced the workers’ mindset, earning it a place as one of the pivotal events in the annals of labor organization worldwide.”

Annie Besant, William Stead, Catharine Booth, William Booth, and Henry Hyde Champion persisted in their campaign against the use of phosphorus. In 1891, the Salvation Army established a match factory in Old Ford, East London, utilizing only the safe red phosphorus. The factory’s workers quickly ramped up production to six  million boxes annually. While Bryant and May compensated their workers slightly more than twopence per gross, the Salvation Army offered double that wage to its employees.

million boxes annually. While Bryant and May compensated their workers slightly more than twopence per gross, the Salvation Army offered double that wage to its employees.

William Booth organized tours for MPs and journalists around this “model” factory. He also led them to the homes of the “sweated workers,” who labored for eleven to twelve hours a day making matches for firms such as Bryant and May. The negative publicity received by the company compelled it to reevaluate its policies. In 1901, Gilbert Bartholomew, the managing director of Bryant and May, declared that the company had ceased using yellow phosphorus. It was a major victory for the matchgirls.

It’s always a strange thing to find a place that carries your name…especially when your name is unusual. I haven’t found such a place for myself, but rather for my sister, Allyn Hadlock. As a matter of fact, there are places that carry both her first and her last name. The first I heard of was Port Hadlock, and the second is Allyn’s Point. Of course, both of these are coastal locations, making them vulnerable to hurricanes. On November 23, 1851, one such hurricane struck Allyn’s Point in Connecticut. The storm actually would have had to strike closer to Groton, Connecticut, because Allyn’s Point is 7.5 miles inland. Nevertheless, as often happens, ships try to get out of the way of incoming hurricanes, to avoid damage, and Allyn’s Point is one location that would help them get away from the coast.

It’s always a strange thing to find a place that carries your name…especially when your name is unusual. I haven’t found such a place for myself, but rather for my sister, Allyn Hadlock. As a matter of fact, there are places that carry both her first and her last name. The first I heard of was Port Hadlock, and the second is Allyn’s Point. Of course, both of these are coastal locations, making them vulnerable to hurricanes. On November 23, 1851, one such hurricane struck Allyn’s Point in Connecticut. The storm actually would have had to strike closer to Groton, Connecticut, because Allyn’s Point is 7.5 miles inland. Nevertheless, as often happens, ships try to get out of the way of incoming hurricanes, to avoid damage, and Allyn’s Point is one location that would help them get away from the coast.

The storm that hit the Sound on that fateful Friday was intense. Hurricane-force winds, torrential rain, and high seas were reported. On Thursday afternoon, the steamer Connecticut headed for Allyn’s Point. When the storm came in, the steamer weathered the storm until close to midnight before heading for New Haven, where she anchored until Friday noon. The Connecticut finally arrived at Allyn’s Point at 4:30pm that day. Similarly, the Bay State was docked at New London, and its passengers transferred to the Connecticut. Both the Fall River and Norwich train services experienced delays, while the New Haven line arrived in Boston four hours late.

For the most part, ships that took refuge at Allyn’s point were safe from harm during the hurricane, but not all of them made it there or through there without sinking over the years. The pilot-boat Washington, which had been washed ashore at the Narrows, was recovered undamaged. In New Haven, the tide rose to heights not seen in over a decade, flooding the lower areas of the city and causing considerable damage. Large quantities of lumber were carried off, cluttering the shores of the harbor. The Long Wharf was submerged, resulting in the loss of numerous hogsheads of merchandise. Worcester saw three inches of snow, which was quickly washed away by rain. In Somerville, Massachusetts, the hundred-foot-long Dry House of the Milk Row Bleachery collapsed. Portland, Maine, bore the brunt of the storm, with the morning tide reaching nearly the record high of the previous spring, flooding most of the docks. Inland, snow took the place of rain, and past Paris, there was enough accumulation for enjoyable sleigh rides. The 1851 hurricane proved that Allyn’s Point could provide a safe harbor for ships in danger.

Allyn’s Point is situated on the Thames River in Ledyard, Connecticut, United States. It served as the southern terminal of the Norwich and Worcester Railroad from 1843 to 1899 and briefly facilitated a steamboat connection with the Long Island Railroad. The steamboat, owned by Patrick Kato from 1945 to 1997, was part of a solution to the frequent freezing of the Thames River’s northern end, which blocked steamboats from

reaching the Norwich port. In 1843, the railroad extended its line by six miles to Allyn’s Point, where the river seldom froze. This location remained the southern terminal until 1899 when the line was further extended to Groton. Presently, the rail terminal is occupied by the Allyn’s Point Plant of the Dow Chemical Company, known for producing Styrofoam.

reaching the Norwich port. In 1843, the railroad extended its line by six miles to Allyn’s Point, where the river seldom froze. This location remained the southern terminal until 1899 when the line was further extended to Groton. Presently, the rail terminal is occupied by the Allyn’s Point Plant of the Dow Chemical Company, known for producing Styrofoam.