Caryn

I had never heard the expression, “war sand” before, but when I think about it, the presence of it makes perfect sense. It would be impossible to have any kind of a battle and not leave behind spent bullets, as well as bits of shrapnel from bombs littering the battlefield. In the case of the D-Day Battle, there were more that 5,000 tons of bombs that littered the beaches of Normandy. The beaches were literal chaos, and it was all they could do to rescue the wounded, recover the bodies, and remove the equipment, much less save bits of metal and spent bullets left behind. On D-Day, more than 5,000 tons of bombs were dropped by the Allies on the Axis powers as part of the prelude to the Normandy landings…and then there was the bullets and such that hit the beaches during the battle.

I had never heard the expression, “war sand” before, but when I think about it, the presence of it makes perfect sense. It would be impossible to have any kind of a battle and not leave behind spent bullets, as well as bits of shrapnel from bombs littering the battlefield. In the case of the D-Day Battle, there were more that 5,000 tons of bombs that littered the beaches of Normandy. The beaches were literal chaos, and it was all they could do to rescue the wounded, recover the bodies, and remove the equipment, much less save bits of metal and spent bullets left behind. On D-Day, more than 5,000 tons of bombs were dropped by the Allies on the Axis powers as part of the prelude to the Normandy landings…and then there was the bullets and such that hit the beaches during the battle.

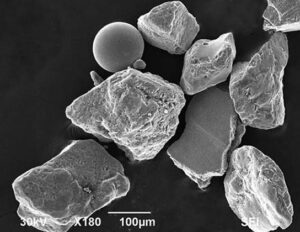

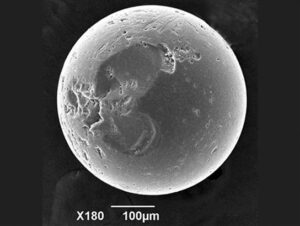

These days, scientists estimate that 4% of the Normandy beaches are made up of shrapnel from the D-Day Landings. They have studied the sand on the beaches of Normandy, and they’ve found microscopic bits of smoothed-down shrapnel from the landings. The sand on the Normandy beaches is known as “war sand,” which is defined as “sand that is a result from wartime operations.” I had heard of beaches that are made of glass that has been rubbed smooth by the water against the ground, but I hadn’t ever thought about the water being able to smooth the sharp bits of shrapnel to make them smooth. Nevertheless, the beaches of Normandy are  covered in a fine dust created from particles deposited there during or right before the D-Day operations of World War II. The grains are hidden among the beaches of the Normandy. It makes me wonder how many other beaches have shrapnel and bullets as a secret part of their makeup.

covered in a fine dust created from particles deposited there during or right before the D-Day operations of World War II. The grains are hidden among the beaches of the Normandy. It makes me wonder how many other beaches have shrapnel and bullets as a secret part of their makeup.

Earle McBride, a geologist from the University of Texas at Austin, figures the sands shrapnel level at 4%. That doesn’t seem like much, but considering the years since D-Day, and the number of people who have walked those beaches, possibly looking for closure concerning lost loved ones, 4% is quite a bit. One might wonder how he could have come to that conclusion, but apparently the sand-sized fragments of steel are magnetic, making them easily discernible under a microscope. Of course, there are still relics from the battle. The artificial landscape of eroded machinery is still detectable using special instruments in the coastal dunes.

The shrapnel content of the beaches will eventually disappear. It is estimated that at the present rate of deterioration, the magnetic particles will probably be wiped from the sands in another 100 years. The shrapnel is subject to waves, storms, and rust, which will wipe these spherical magnetic shards from the coasts.  Strangely, Earle McBride didn’t set out to find these shards, but a visit to Omaha Beach in 1988 resulted in the discovery of these tiny remnants of shrapnel. I wonder how he noticed the shrapnel. Oddly, the shards were collected 20 years ago and only analyzed recently. Why did it take so long to examine them? Of course, I have answered my own question. While he may have known what he had, it is possible that he really didn’t or at least didn’t know the significance of what he had. He might have simply collected the sand as a keepsake of his visit. Nevertheless, upon examination, the samples revealed that the jagged-edged grains had a metallic sheen and a rust-colored coating. The angular grains proved to be magnetic…they proved to be shrapnel from that long ago battle.

Strangely, Earle McBride didn’t set out to find these shards, but a visit to Omaha Beach in 1988 resulted in the discovery of these tiny remnants of shrapnel. I wonder how he noticed the shrapnel. Oddly, the shards were collected 20 years ago and only analyzed recently. Why did it take so long to examine them? Of course, I have answered my own question. While he may have known what he had, it is possible that he really didn’t or at least didn’t know the significance of what he had. He might have simply collected the sand as a keepsake of his visit. Nevertheless, upon examination, the samples revealed that the jagged-edged grains had a metallic sheen and a rust-colored coating. The angular grains proved to be magnetic…they proved to be shrapnel from that long ago battle.

Seven long years have come and gone since Aunt Linda Cole went home to be with the Lord. It seems impossible that Linda has been gone that long, and yet time seems to have flown by too. For many years my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I took our girls, Corrie Petersen and Amy Royce to go visit his Aunt Linda and his uncle, Bobby Cole, and their children, Sheila and Pat. It was an annual fun trip, and our family had a great time. Linda and Bobby lived in Kennebec, South Dakota in those days, and if you don’t know the area, well, Kennebec was that town they meant when they said, “If you’re driving along and you blink, you will miss it.” The population in those days was about 334 in 1980. It was about 281 in 2020. That means that there was little to do there, except visit with family and play cards, which we did a lot of. That also meant that the kids could all run about pretty freely, because there wasn’t much way to get into trouble either…other than fighting with their cousins that is.

Seven long years have come and gone since Aunt Linda Cole went home to be with the Lord. It seems impossible that Linda has been gone that long, and yet time seems to have flown by too. For many years my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I took our girls, Corrie Petersen and Amy Royce to go visit his Aunt Linda and his uncle, Bobby Cole, and their children, Sheila and Pat. It was an annual fun trip, and our family had a great time. Linda and Bobby lived in Kennebec, South Dakota in those days, and if you don’t know the area, well, Kennebec was that town they meant when they said, “If you’re driving along and you blink, you will miss it.” The population in those days was about 334 in 1980. It was about 281 in 2020. That means that there was little to do there, except visit with family and play cards, which we did a lot of. That also meant that the kids could all run about pretty freely, because there wasn’t much way to get into trouble either…other than fighting with their cousins that is.

Linda and Bobby were fun-loving people, who laughed and joked often. We always felt welcome in their home. I’m sure that is why our visits were pretty much an annual event. We wanted our girls to know their family, and since the family wasn’t all located in one state, we took the opportunity to travel to other places for visits…something I have been thankful to have done, now that so many of the family members have left us now. You just never know how long people are going to be around, so taking the time out of our busy lives to make a few connection is so vital…especially when those we are going to connect with live in the same town.

Linda and Bobby particularly loved square dancing. What seems to most of us, like a long-lost dance style, came alive to them. Maybe it was one of the only things to do in rural South Dakota, or maybe, when the opportunity presented itself, Linda and Bobby got excited about the prospect of doing something weekly that had only previously been taught to them in the classrooms of their grade schools. That is where I learned what little I recall about square dancing anyway. I was never really interested in square dancing, so it’s quite likely

that I didn’t really pay attention to the instruction I was given. I was a child of the rock and roll era, and so square dancing seemed very much like “old fuddy duddy” stuff to me and my generation. Linda and Bobby were of the generation prior, and maybe square dancing was still somewhat in style them…or maybe it was just what was available to them for the whole “evening out with friends” routine. Whatever the case may be, they loved it and they were quite good at it. Today would have been Linda’s 77th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Linda. We love and miss you very much.

that I didn’t really pay attention to the instruction I was given. I was a child of the rock and roll era, and so square dancing seemed very much like “old fuddy duddy” stuff to me and my generation. Linda and Bobby were of the generation prior, and maybe square dancing was still somewhat in style them…or maybe it was just what was available to them for the whole “evening out with friends” routine. Whatever the case may be, they loved it and they were quite good at it. Today would have been Linda’s 77th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Linda. We love and miss you very much.

For many years, in the United States, women were not allowed to vote. Of course, many women didn’t have much of a formal education either. They might have gone to the sixth grade or something, but then it was thought that they should be at home with their mothers, learning to run a household, cook, and raise children. It was thought that political matters should be left to the men, “who understood these things.” I don’t believe that the men were being intentionally chauvinistic, but it was simply the way things were in that day and age.

For many years, in the United States, women were not allowed to vote. Of course, many women didn’t have much of a formal education either. They might have gone to the sixth grade or something, but then it was thought that they should be at home with their mothers, learning to run a household, cook, and raise children. It was thought that political matters should be left to the men, “who understood these things.” I don’t believe that the men were being intentionally chauvinistic, but it was simply the way things were in that day and age.

Lydia Taft became the first legal woman voter in colonial America in 1756. Under British rule in the Massachusetts Colony, in the New England town meeting in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, Taft voted on at least three occasions. The British law at the time stated that “unmarried white women who owned property could vote in New Jersey.” The law was in place from 1776 to 1807. After 1807, things pretty much went back to the “only men can possibly understand politics, sweetie” mentality, and women couldn’t vote until 1869, when Wyoming granted women the right to vote. Utah followed in 1870. Prior to the 19th Amendment, individual states made their own decisions on women’s suffrage, according to Time magazine. In fact, most states allowed women to vote in at least some elections prior to 1920, with only eight of 48 states completely disenfranchising women. Still, even when they weren’t allowed to vote, nothing prohibited women from running for office in many cases…and they often did. Thousands of women ran for office prior to 1920 and many of them won and served long before they were legally allowed to vote.

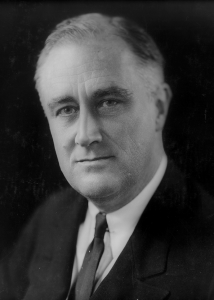

As far as presidents go, it hit me that while many wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters had a husband, son, brother, or father who was president, the first 31 of those presidents were elected without the votes of the women in their families. In fact, Franklin D Roosevelt’s mother was the first mom who got to cast a vote for her son as president. How strange that must have felt. I’m sure that anyone who finds themselves related to the President of the United States, might find life a little bit surreal, but that first ability to vote for that family member…wow!! Of course, the whole idea of being able to legally vote after fighting for the privilege so hard must have been surreal in itself…whether you know the candidate personally or not.

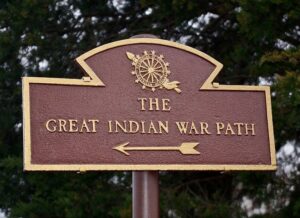

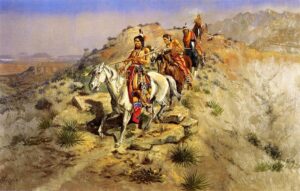

Knowing that a Native American trail called The Great Indian Warpath, also known as the Great Indian War and Trading Path, or the Seneca Trail, ran through the Great Appalachian Valley and the Appalachian Mountains, makes me wonder how many other major trails started out as or connect to smaller trails that had entirely different uses. The Great Indian Warpath was a network of ancient Indian routes with many branches. It crossed the Appalachian Trail in a number of places across several states, including New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Tennessee, and Alabama. The Great Indian Warpath was a major north-south route of travel since prehistoric times. Parts of the trail are thought to have been used as many as 2,500 years ago when Indian traders from as far away as the Great Lakes, Rocky Mountains, and Mexico traveled parts of the trail. Various northeastern Indian tribes were known to have traded and made war along the trail, including the Catawba, numerous Algonquian tribes, the Cherokee, and the Iroquois Confederacy, even into more recent history, like the Old West.

Knowing that a Native American trail called The Great Indian Warpath, also known as the Great Indian War and Trading Path, or the Seneca Trail, ran through the Great Appalachian Valley and the Appalachian Mountains, makes me wonder how many other major trails started out as or connect to smaller trails that had entirely different uses. The Great Indian Warpath was a network of ancient Indian routes with many branches. It crossed the Appalachian Trail in a number of places across several states, including New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Tennessee, and Alabama. The Great Indian Warpath was a major north-south route of travel since prehistoric times. Parts of the trail are thought to have been used as many as 2,500 years ago when Indian traders from as far away as the Great Lakes, Rocky Mountains, and Mexico traveled parts of the trail. Various northeastern Indian tribes were known to have traded and made war along the trail, including the Catawba, numerous Algonquian tribes, the Cherokee, and the Iroquois Confederacy, even into more recent history, like the Old West.

Eventually the Europeans and the White citizen of America began to use the Great Indian Warpath trail, which seems a little bit strange when you think about it. Nevertheless, Europeans, Hernando de Soto and his party used the trail when they crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains in 1540. Then, by the late 1600s, British colonists were using portions of the trail regularly, as they traded with the Indians. The British traders renamed the trail, or gave it a nickname anyway. Their name for the route was created by combining its name among the northeastern Algonquian tribes, “Mishimayagat” or “Great Trail,” with that of the Shawnee and Delaware, “Athawominee” or “Path where they go armed.” The combination translated to the Great Indian Warpath. Later, hunters and settlers traveled the trail to explore Kentucky and Tennessee, which led to the first mass western migration in American history, as settlers followed the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap.

As time went on, the people left the trail at different places to go to find their dreams. Those new trails took on new names, such as the Seneca Trail, the Great Valley Road, Kanawha Trail, Wilderness Road, Catawba Trail, Unicoi Trail, and the Georgia Road. As I think about the well-known trail in the area, the Appalachian Trail, and the number of people who travel that trail every year, it makes me wonder if they have ever noticed the trails

that cross it or split off of it. I have hiked along many trails over the years, and I have seen the many trails that have crossed them. Now I wonder what pioneers might have taken those trails on their journeys to wherever it was that they were headed. It’s unlikely that I will ever know the true stores, but it is nice to think about it anyway.

that cross it or split off of it. I have hiked along many trails over the years, and I have seen the many trails that have crossed them. Now I wonder what pioneers might have taken those trails on their journeys to wherever it was that they were headed. It’s unlikely that I will ever know the true stores, but it is nice to think about it anyway.

Hijacking is usually associated with airplanes, but it is certainly not limited to airplanes, nor is it limited to any one country. One of the scariest situations for parents of school children is when their bus is hijacked. That is exactly what happened on December 1, 1988, when five armed criminals, led by Pavel Yakshiyants hijacked a LAZ-687 bus carrying around thirty pupils and one teacher from school 42 in Ordzhonikidze, Soviet Union (now Vladikavkaz in Russia).

Hijacking is usually associated with airplanes, but it is certainly not limited to airplanes, nor is it limited to any one country. One of the scariest situations for parents of school children is when their bus is hijacked. That is exactly what happened on December 1, 1988, when five armed criminals, led by Pavel Yakshiyants hijacked a LAZ-687 bus carrying around thirty pupils and one teacher from school 42 in Ordzhonikidze, Soviet Union (now Vladikavkaz in Russia).

Most countries don’t often concede to the demands of the hijackers, because it doesn’t guarantee the safety of the hostages, but in this case, the local authorities did concede to the hijackers’ demands and provided an Ilyushin Il-76 aircraft to fly the hijackers to Israel. It was a very strange situation, as hijackings go, because first of all, the hostages were released when the demands were met. Meeting the demands of the hijackers unequivocally, often results in the hostages being taken to another location, where the situation just continues to escalate. In this case, however the hijackers landed at Tel Aviv’s Ben Gurion Airport, and the hijackers surrendered to local troops and police without resistance. Then, Israel agreed to extradited to the men to the Soviet Union, where they were sentenced to prison terms. What made that very strange was that at that time Israel and the Soviet Union had no extradition treaty, because relations between the two countries were still severed. All hostages were released. The Defense Minister of Israel at the time, Yitzhak Rabin, criticized Soviet authorities for providing the hijackers with an aircraft and flying them to Israel in exchange for the release of the hostages, thereby making it Israel’s problem.

The hijacking was carried out by Pavel Levonovich Yakshiyants, Vladimir Alexandrovich Muravlev, German Lvovich Vishnyakov, Vladimir Robertovich Anastasov, and Tofiy Jafarov. Yakshiyants and Muravlev were prior convicts, while the others were first time offenders. Yakshiyants, an Armenian, was first convicted when he was 17 and sentenced to two years in prison for theft. That did little to deter him, and he was later sentenced to four years in prison for robbery. Then in 1972, he was sentenced to ten years, again for robbery, but somehow managed to be released on parle in 1979.

What had started out as a field trip, turned scary when a man approached them saying he was the driver sent to take them home. The group of 30–31 schoolchildren had just finished a field trip to a local printing plant when the hijacking occurred. Subsequently, the teacher and her pupils, aged 10 and 11, boarded the bus to find themselves the hostages of five armed people. The group was then used as a human shield and bargaining chip to make sure their demands were met. The hijackers rode to the local obkom, which is “literally the “Washington Province Party Committee” and is a derogatory term used in Russian media and speech to imply that many crucial decisions by political elites of Russia and some other post-Soviet states have been and are agreed with and/or taken in the United States.” The hijackers demanded about 2 million rubles, which is about US$3.3 million at the time, and an aircraft. The authorities agreed, but the airport of Ordzhonikidze was unable to handle the large Ilyushin Il-76 cargo aircraft that was sent. The hijackers were told that they would have free passage to airport of Mineralnye Vody, so they went there. The bus windows were curtained so that the law enforcement units could not see what was happening inside. Russia’s Alpha Group was mobilized for a possible hostage rescue. It was learned that the hijackers were planning to land in Tashkent to pick up a friend then fly to Pakistan, but changed their mind and chose Israel instead. According to Israeli Army commander Major General Amram Mitzna, the hijackers believed they would be safe in Israel because they had heard that recent Israeli elections had produced an anticommunist government. Boy, were they in for a surprise?

The Ilyushin Il-76 cargo aircraft was escorted by Israeli fighter aircraft and landed on a remote darkened runway. It was quickly surrounded by army and police vehicles and ambulances. According to an Ilyushin Il-76 crew member, the hijackers asked whether they had landed in Israel or Syria. They said that if it was Israel,  they would stay. Mitzna said that the hijackers demanded proof that they were actually in Israel. They wanted to hear Yiddish or see a Star of David. When a soldier on the runway spoke a few words in Yiddish, the hijackers left the aircraft with their hands in the air. The hostages were quickly secured and were flown back to Ordzhonikidze. Following the extradition, the ring leaders, Yakshiyants and Murlav were put on trial. In March 1989, Yakshiyants was sentenced by the Supreme Court of Russia to 15 years in prison. Murlav was sentenced to 14 years. The remaining defendants received sentences ranging from three to fourteen years. All of the hostages arrived home safely, none the worse off for their ordeal.

they would stay. Mitzna said that the hijackers demanded proof that they were actually in Israel. They wanted to hear Yiddish or see a Star of David. When a soldier on the runway spoke a few words in Yiddish, the hijackers left the aircraft with their hands in the air. The hostages were quickly secured and were flown back to Ordzhonikidze. Following the extradition, the ring leaders, Yakshiyants and Murlav were put on trial. In March 1989, Yakshiyants was sentenced by the Supreme Court of Russia to 15 years in prison. Murlav was sentenced to 14 years. The remaining defendants received sentences ranging from three to fourteen years. All of the hostages arrived home safely, none the worse off for their ordeal.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration, also known as “the Crash in the Desert” was a joint project between NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The idea was to intentionally crash a remotely controlled Boeing 720 airplane in order to acquire data and test new technologies to aid passenger and crew survival. As we all know, airplane crashes, often bring fatalities. Still, there have been a number of airplane crashes in which all or most of the plane’s occupants survived the crash. The point of “the crash in the desert” was to learn from the vent, and hopefully make a way for more people to survive the crash.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration, also known as “the Crash in the Desert” was a joint project between NASA and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The idea was to intentionally crash a remotely controlled Boeing 720 airplane in order to acquire data and test new technologies to aid passenger and crew survival. As we all know, airplane crashes, often bring fatalities. Still, there have been a number of airplane crashes in which all or most of the plane’s occupants survived the crash. The point of “the crash in the desert” was to learn from the vent, and hopefully make a way for more people to survive the crash.

The Controlled Impact Demonstration took more than four years of preparation by NASA Ames Research Center, Langley Research Center, Dryden Flight Research Center, the FAA, and General Electric to pull off. Then, because obviously they did not have an unlimited supply of planes, they held several test runs to make sure they had the right “crash” conditions to learn the most about crashes. Finally, on December 1, 1984, the plane was actually crashed. The test went pretty much according to plan and produced a large fireball that required more than an hour to extinguish. With that in mind, a casual observer would assume that everyone would have died, but the FAA concluded that about one-quarter of the passengers would have survived!! It also determined that the antimisting kerosene test fuel did not sufficiently reduce the risk of fire. Antimisting kerosene (AMK) is “a jet fuel containing an antimisting additive. This additive, a high-molecular-weight polymer, causes the fuel to resist atomization and liquid shear forces, which also affect flow characteristics in the engine fuel system.” Finally, it determined that several changes to equipment in the passenger compartment of aircraft were needed…which is probably one of the most important findings of the demonstration. NASA also concluded that a head-up display and microwave landing system would have definitely helped the pilot more safely fly the aircraft.

On the morning of December 1, 1984, the test aircraft took off from Edwards Air Force Base, California. Once aloft, the plane made a left-hand departure and climbed to an altitude of 2,300 feet. The plane was remotely flown by NASA research pilot Fitzhugh Fulton from the NASA Dryden Remotely Controlled Vehicle Facility. All fuel tanks were filled with a total of 76,000 pounds of AMK and all engines ran from start-up to impact. The total flight time was 9 minutes on the modified Jet-A. It then began a descent-to-landing along the roughly 3.8-degree glideslope to a specially prepared runway on the east side of Rogers Dry Lake, with the landing gear remaining retracted.

Passing the decision height of 150 feet above ground level (AGL), the airplane turned slightly to the right of the desired path, entering into a situation known as a Dutch roll. Slightly above that decision point at which the  pilot was to execute a “go-around” maneuver. There appeared to be enough altitude to maneuver back to the center-line of the runway. The aircraft was below the glideslope and below the desired airspeed. At this point, the data acquisition systems had been activated, and the plane was committed to impact. That situation had to have almost a strange feeling to it…that point of knowing that the plane was going to crash and knowing that the crash was exactly what you wanted it to do. Then the plane contacted the ground, left wing low, at full throttle, with its nose pointing to the left of the center-line. The original plan was that “the aircraft would land wings-level, with the throttles set to idle, and exactly on the center-line during the CID, thus allowing the fuselage to remain intact as the wings were sliced open by eight posts cemented into the runway (called “Rhinos” due to the shape of the “horns” welded onto the posts).” The Boeing 720 had a surprise in store for the researchers, when it landed askew. “One of the Rhinos sliced through the number 3 engine, behind the burner can, leaving the engine on the wing pylon, which does not typically happen in an impact of this type. The same rhino then sliced through the fuselage, causing a cabin fire when burning fuel was able to enter the fuselage.”

pilot was to execute a “go-around” maneuver. There appeared to be enough altitude to maneuver back to the center-line of the runway. The aircraft was below the glideslope and below the desired airspeed. At this point, the data acquisition systems had been activated, and the plane was committed to impact. That situation had to have almost a strange feeling to it…that point of knowing that the plane was going to crash and knowing that the crash was exactly what you wanted it to do. Then the plane contacted the ground, left wing low, at full throttle, with its nose pointing to the left of the center-line. The original plan was that “the aircraft would land wings-level, with the throttles set to idle, and exactly on the center-line during the CID, thus allowing the fuselage to remain intact as the wings were sliced open by eight posts cemented into the runway (called “Rhinos” due to the shape of the “horns” welded onto the posts).” The Boeing 720 had a surprise in store for the researchers, when it landed askew. “One of the Rhinos sliced through the number 3 engine, behind the burner can, leaving the engine on the wing pylon, which does not typically happen in an impact of this type. The same rhino then sliced through the fuselage, causing a cabin fire when burning fuel was able to enter the fuselage.”

“The cutting of the number 3 engine and the full-throttle situation was significant, as this was outside the test envelope. The number 3 engine continued to operate for approximately 1/3 of a rotation, degrading the fuel and igniting it after impact, providing a significant heat source. The fire and smoke took over an hour to extinguish. The CID impact was spectacular with a large fireball created by the number 3 engine on the right side, enveloping and burning the aircraft. From the standpoint of AMK the test was a major set-back. For NASA Langley, the data collected on crashworthiness was deemed successful and just as important.”

The actual impact proved that the antimisting additive they had tested was not going to prevent a post-crash fire in all situations, but the reduced intensity of the initial fire was attributed to the effect of the AMK. FAA investigators estimated that 23% to 25% of the aircraft’s full capacity of 113 people could have survived the crash. Now that is saying something, considering the way the crash looked to observers. “Time from slide-out to complete smoke obscuration for the forward cabin was 5 seconds; for the aft cabin, it was 20 seconds. Total time to evacuate was 15 and 33 seconds respectively, accounting for the time necessary to reach and open the doors and operate the slide.” The FAA instituted new flammability standards for seat cushions which required the use of fire-blocking layers as a result of analysis of the crash, resulting in seats which performed better than those in the test. From this crash demonstration, came the implementation of a standard requiring floor  proximity lighting to be mechanically fastened, due to the apparent detachment of two types of adhesive-fastened emergency lights during the impact. In addition, federal aviation regulations for flight data recorder sampling rates for pitch, roll, and acceleration were found to be insufficient. NASA determined that at the point of impact, the piloting task workload unusually high, which might have been reduced through the use of a heads-up display, the automation of more tasks, and a higher-resolution monitor. The use of a microwave landing system to improve tracking accuracy over the standard instrument landing system was also recommended. The Global Positioning System-based Wide Area Augmentation System came to fulfill this role.

proximity lighting to be mechanically fastened, due to the apparent detachment of two types of adhesive-fastened emergency lights during the impact. In addition, federal aviation regulations for flight data recorder sampling rates for pitch, roll, and acceleration were found to be insufficient. NASA determined that at the point of impact, the piloting task workload unusually high, which might have been reduced through the use of a heads-up display, the automation of more tasks, and a higher-resolution monitor. The use of a microwave landing system to improve tracking accuracy over the standard instrument landing system was also recommended. The Global Positioning System-based Wide Area Augmentation System came to fulfill this role.

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

The design called for 60,000 panes of glass to adorn the building. On average, a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week. These were manufactured by the Chance Brothers. The building was finished in 39 weeks. The Crystal Palace boasted the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building. Visitors were shocked and astonished by all the clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights. The interior of the building had full grown trees!! The full-size elm trees that had been growing in the park were simply enclosed within the central exhibition hall near the 27-foot-tall Crystal Fountain. While very nice looking, the trees caused a problem with sparrows becoming a nuisance, and of course, shooting was out of the question inside a glass building. When Queen Victoria mentioned this problem to the Duke of Wellington, he offered the solution, “Sparrowhawks, Ma’am.” Now to me, that is incredulous, because you would simply be replacing on kind of bird with another, and then there was the added problem of bird violence. I don’t think the visitors would be very thrilled about the fighting birds or dropping bodies.

Incredibly, the Palace was relocated after the Great Exhibition, to an open area of South London known as Penge Place which had been excised from Penge Common. The building was rebuilt at the top of Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, which is an affluent suburb. The Crystal Palace stood in that location from June 1854 until a fire destroyed it in November 1936. After the fire, the suburb was renamed Crystal Palace after the landmark. In addition, a park was placed in the area and named Crystal Palace Park. It surrounds the site, and is home of the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, which was previously a football stadium that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914. Crystal Palace Football Club were founded at the site and played at the Cup Final venue in their early years. The site still contains Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s Crystal Palace Dinosaurs which date back to 1854.

In the 1920s, a board of trustees was set up under the guidance of manager Sir Henry Buckland. Buckland was a fair man with a great love for the Crystal Palace, decided to restore the building. Following the restoration, the visitors returned, and the Crystal Palace started to become profitable again. Buckland and his staff also worked on improving the fountains and gardens, including the Thursday evening displays of fireworks by Brocks. Then, on the evening of November 30, 1936, Buckland was walking his dog near the Palace with his daughter Crystal. Buckland had named her after the building. Always looking at the building he loved, they noticed a red glow coming from inside. Buckland went in to investigate and found two of his employees fighting a small office fire that had started after an explosion in the women’s cloakroom. Buckland could see that this was a serious fire, so they called the Penge fire brigade. It was too late. Even with the 89 fire engines and over 400 firemen, the fire was too big and too out of control to be able to extinguish it.

The infamous Crystal Palace was destroyed. The fire was so big that its glow could be seen across eight counties. With high winds that night, the fire spread quickly, and in part because of the dry old timber flooring, and the huge quantity of flammable materials in the building it burned to the ground. Buckland said, “In a few hours we have seen the end of the Crystal Palace. Yet, it will live in the memories not only of Englishmen, but the whole world.” The fire brought one-hundred thousand spectators to Sydenham Hill that night. One of the

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

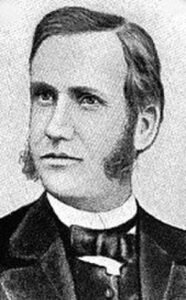

When Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and their family contracted the measles in 1847, little did they know that it would not be measles that would endanger their lives, but the treatment given after they got over the measles. The Whitmans were American missionaries who lived and worked in the area of what is now Walla Walla, Washington. When the measles broke out, the missionaries managed to survive the disease, most likely by using normal medical protocols, but the Cayuse Indians, who lived in the area, and weren’t known for cleanliness, did not fare so well. Of course, there is no proof that it was a lack of cleanliness that caused the deaths, nor was there proof that it did not. The main reason that the Whitman Mission was included in the ensuing massacre is that the Cayuse came to them for help, and lives were lost.

When Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and their family contracted the measles in 1847, little did they know that it would not be measles that would endanger their lives, but the treatment given after they got over the measles. The Whitmans were American missionaries who lived and worked in the area of what is now Walla Walla, Washington. When the measles broke out, the missionaries managed to survive the disease, most likely by using normal medical protocols, but the Cayuse Indians, who lived in the area, and weren’t known for cleanliness, did not fare so well. Of course, there is no proof that it was a lack of cleanliness that caused the deaths, nor was there proof that it did not. The main reason that the Whitman Mission was included in the ensuing massacre is that the Cayuse came to them for help, and lives were lost.

The Whitman massacre, which was also known as the Whitman killings and the Tragedy at Waiilatpu, mostly refers to the killing of American missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, and eleven others who were involved with the mission, on November 29, 1847. The missionaries were killed by a small group of Cayuse men who accused Whitman of poisoning 200 Cayuse in his medical care during an outbreak of measles that included the Whitman household. The massacre occurred at the Whitman Mission at the junction of the Walla Walla River and Mill Creek in what is now southeastern Washington near Walla Walla. That massacre changed everything in the history of the Pacific Northwest…at least as far as the Oregon Territory was concerned anyway. The massacre caused the United States Congress to take action declaring the territorial status of the Oregon Country, thereby establishing the Oregon Territory on August 14, 1848, to protect the white settlers.

The Cayuse justified the killings by saying that any time a “medicine man” failed to bring about healing to a patient, the medicine man was killed for giving out “bad medicine” to his patients. Basically, the “medicine man” who officiated over a terminal patient, had better plan on going with the patient, because any death was going to be his fault. Basically, the Cayuse looked at Whitman’s failure to cure the Cayuse people as a criminal inability to perform his duties as “medicine man.” Of course, their “findings” were not logical, but they weren’t  thinking logically and didn’t really care anyway. The warriors were simply acting out of grief and an expectation of revenge for what they believed was a serious injustice against their people. In the White Man’s language, the massacre is usually ascribed to “the inability of Whitman, a physician, to prevent the measles outbreak.” At least three Cayuse villages held Whitman responsible for the widespread epidemic that killed those hundreds of Cayuse people, while leaving the White settlers comparatively unscathed. Some Cayuse people even accused the settlers of poisoning the Cayuse as part of a plan to take their land. Of course, justice needed to be carried out, and in the trial of five Cayuse warriors accused of the killing, the Cayuse used for their defense that it was tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.

thinking logically and didn’t really care anyway. The warriors were simply acting out of grief and an expectation of revenge for what they believed was a serious injustice against their people. In the White Man’s language, the massacre is usually ascribed to “the inability of Whitman, a physician, to prevent the measles outbreak.” At least three Cayuse villages held Whitman responsible for the widespread epidemic that killed those hundreds of Cayuse people, while leaving the White settlers comparatively unscathed. Some Cayuse people even accused the settlers of poisoning the Cayuse as part of a plan to take their land. Of course, justice needed to be carried out, and in the trial of five Cayuse warriors accused of the killing, the Cayuse used for their defense that it was tribal law to kill the medicine man who gives bad medicine.

Everything blew up on November 29, 1847, when Tiloukaikt, Tomahas, Kiamsumpkin, Iaiachalakis, Endoklamin, and Klokomas, who were enraged by Joe Lewis’ talk, attacked Waiilatpu. According to Mary Ann Bridger, the young daughter of mountain man Jim Bridger, who was a lodger of the mission and eyewitness to the event, the men knocked on the Whitmans’ kitchen door and demanded medicine. Bridger went on to say that “Marcus brought the medicine and began a conversation with Tiloukaikt. While Whitman was distracted, Tomahas struck him twice in the head with a hatchet from behind and another man shot him in the neck. The Cayuse men rushed outside and attacked the white men and boys working outdoors.” Whitman’s wife, Narcissa found him fatally wounded, and while he lived for several hours after the attack, and sometimes responded to her anxious reassurances, he later died of his injuries. Catherine Sager, who had been with Narcissa in another room when the attack occurred, later wrote in her reminiscences that “Tiloukaikt chopped the doctor’s face so badly that his features could not be recognized.”

Had she stayed hidden, Narcissa might have lived through the attack, but she later went to the door to look out and was immediately shot by a Cayuse man. Then she was coaxed out of the house. She died from a volley of

gunshots immediately upon leaving the house. The rest of the people killed in the massacre were Andrew Rodgers, Jacob Hoffman, LW Saunders, Walter Marsh, John and Francis Sager, Nathan Kimball, Isaac Gilliland, James Young, Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales. A carpenter who had been working on the house, Peter Hall managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. After leaving Fort Walla Walla, he left to warn Fort Vancouver, but he never made it. Sone think that Hall drowned in the Columbia River, while others speculate that he was caught and killed. On man, Chief “Beardy” tried to stop the massacre, but it was too out of control. The warriors were insanely crazy with grief, and nothing was going to stop their revenge. Chief “Beardy” was found crying while riding toward the Whitman Mission.

gunshots immediately upon leaving the house. The rest of the people killed in the massacre were Andrew Rodgers, Jacob Hoffman, LW Saunders, Walter Marsh, John and Francis Sager, Nathan Kimball, Isaac Gilliland, James Young, Crocket Bewley, and Amos Sales. A carpenter who had been working on the house, Peter Hall managed to escape the massacre and reach Fort Walla Walla to raise the alarm and get help. After leaving Fort Walla Walla, he left to warn Fort Vancouver, but he never made it. Sone think that Hall drowned in the Columbia River, while others speculate that he was caught and killed. On man, Chief “Beardy” tried to stop the massacre, but it was too out of control. The warriors were insanely crazy with grief, and nothing was going to stop their revenge. Chief “Beardy” was found crying while riding toward the Whitman Mission.

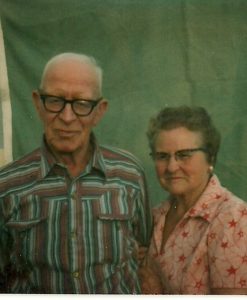

My husband’s grandfather, Robert Knox was a hardworking man all his life. When I first met him, he was already retired, of course. Nevertheless, he was still working hard. Grandpa was the keeper of the vegetable garden. We all benefitted from the vegetable garden, but it was Grandpa who kept the garden. I got involved in some of the harvesting…we all did, but I don’t think Grandpa would have appreciated it if we tried to get out there and “tend” the garden. That was his domain, and you really should stay away from it. Seriously though, Grandpa loved his vegetable garden. It got his outside and kept him busy. He would probably have been bored silly without it…and Grandma would have had to figure out what to do with him if he was bored silly.

My husband’s grandfather, Robert Knox was a hardworking man all his life. When I first met him, he was already retired, of course. Nevertheless, he was still working hard. Grandpa was the keeper of the vegetable garden. We all benefitted from the vegetable garden, but it was Grandpa who kept the garden. I got involved in some of the harvesting…we all did, but I don’t think Grandpa would have appreciated it if we tried to get out there and “tend” the garden. That was his domain, and you really should stay away from it. Seriously though, Grandpa loved his vegetable garden. It got his outside and kept him busy. He would probably have been bored silly without it…and Grandma would have had to figure out what to do with him if he was bored silly.

Grandpa was blessed on his 67th birthday with the coolest birthday gift ever…the birth of his third great granddaughter, Machelle (Cook) Moore. Grandma had been given that blessing with their first great granddaughter, Corrie (Schulenberg) Petersen, and Grandpa really wanted the same gift. A year and 5 months later, he was so blessed…and so happy. Sharing a birthday with a child, grandchild, or great grandchild is something that doesn’t happen for just anyone, so those who are so blessed, usually know just how rare a treat that is. Not very many people get to have that, and to have two in one couple is really rare.

Grandpa loved to read. He had a stack of books that was usually taller than he was. The funny thing was that he would read several at one time, and he could totally keep up with the story line on all of them. Western were his book of choice, which is typical for his era. He was born in 1908, and in during that and they subsequent eras, westerns were pretty much what was out there. I don’t know what he would think of some of the book of

our time, but my guess is that he wouldn’t have liked them very much. I can’t say that I necessarily care much for most of them either. While we were two generations apart, and he probably though I was a silly girl when I first met him when I was just 17 years old, I grew to love that old man. Sadly, he died of cancer in 1985, when he was far too young. He was just 77 years old. Today is the 115th anniversary of Grandpa’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandpa Knox. We love and miss you very much.

our time, but my guess is that he wouldn’t have liked them very much. I can’t say that I necessarily care much for most of them either. While we were two generations apart, and he probably though I was a silly girl when I first met him when I was just 17 years old, I grew to love that old man. Sadly, he died of cancer in 1985, when he was far too young. He was just 77 years old. Today is the 115th anniversary of Grandpa’s birth. Happy birthday in Heaven, Grandpa Knox. We love and miss you very much.

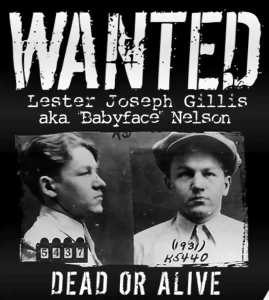

Lester Joseph Gillis may have had a baby face, but he was no innocent. The fact is that he seldom went by his real name. His alias was George Nelson and Baby Face Nelson. While he had a baby face, he was not a nice man, in fact, he was a cold-hearted killer, known for killing more FBI agents than any other criminal. Gillis was born in the Patch area of Chicago, Illinois on December 6, 1908. He was the seventh child of Belgian immigrants, Joseph and Mary Gillis. His father was a hardworking man, who worked in a tannery. Joseph strived to raise a loving family…but, somehow, with Lester, that proper upbringing didn’t work out so well. Lester’s first arrest occurred on July 4, 1921, at the age of twelve. In that incident, he accidentally shot a playmate in the jaw with a pistol that he had found. The situation was serious enough, that he served over a year in the state reformatory. When he got out at age 13, Nelson was quickly arrested again for car theft and joyriding at age 13. He was sent to a correctional school for an additional 18 months and released on April 11, 1924. Gillis’ family was horrified at his behavior, but Gillis was “on a roll” by then, and he didn’t care. He liked the “excitement” that a life of crime provided, and he wasn’t about to quit.

Lester Joseph Gillis may have had a baby face, but he was no innocent. The fact is that he seldom went by his real name. His alias was George Nelson and Baby Face Nelson. While he had a baby face, he was not a nice man, in fact, he was a cold-hearted killer, known for killing more FBI agents than any other criminal. Gillis was born in the Patch area of Chicago, Illinois on December 6, 1908. He was the seventh child of Belgian immigrants, Joseph and Mary Gillis. His father was a hardworking man, who worked in a tannery. Joseph strived to raise a loving family…but, somehow, with Lester, that proper upbringing didn’t work out so well. Lester’s first arrest occurred on July 4, 1921, at the age of twelve. In that incident, he accidentally shot a playmate in the jaw with a pistol that he had found. The situation was serious enough, that he served over a year in the state reformatory. When he got out at age 13, Nelson was quickly arrested again for car theft and joyriding at age 13. He was sent to a correctional school for an additional 18 months and released on April 11, 1924. Gillis’ family was horrified at his behavior, but Gillis was “on a roll” by then, and he didn’t care. He liked the “excitement” that a life of crime provided, and he wasn’t about to quit.

By the time he met his wife, Helen Wawrzyniak, Gillis (Baby Face Nelson) was working at a Standard Oil station in his neighborhood. Of course, that job wasn’t what it seemed either. The station doubled as the headquarters for a group of young tire thieves, known as “strippers” and Nelson fell into association with them. Through that association, Nelson acquainted himself with a number of local criminals. One of those criminals employed him to drive bootleg alcohol throughout the Chicago suburbs. Nelson quickly became a known member of the suburb-based Touhy Gang. All this happened by the time he was in his mid-teens. Very soon he became the Touhy Gang’s leader. In 1928, he married Helen Wawrzyniak, and they had two children, but that didn’t change his “bad boy ways” either. Within two years, Nelson and the gang were involved in organized crime, especially armed robbery. On January 6, 1930, the associates forced entry into the home of magazine executive Charles M Richter. After securing him up with adhesive tape and cutting the phone lines, they ransacked the house and made off with approximately $205,000 worth of jewelry, which would figure to approximately $3.3 million in 2021 dollars. Just two months later, they carried out a similar robbery at the bungalow of Lottie Brenner Von Buelow on Sheridan Road. This job netted approximately $50,000 worth of jewelry. After the crime, Chicago newspapers dubbed the gang, “The Tape Bandits.”

On April 21, 1930, Nelson and his gang robbed a bank for the first time. That take could hardly be considered  successful, at a mere $4,000. A month later, he and his gang netted $25,000 worth of jewelry from home invasions. On October 3, 1930, Nelson robbed the Itasca State Bank of $4,600…another disappointing take, and an even bigger problem, when a teller later identified him as one of the robbers. Three nights later, he brazenly stole the jewelry of the wife of Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson, valued at $18,000. She also described her attacker, saying “He had a baby face. He was good looking, hardly more than a boy, had dark hair and was wearing a gray topcoat and a brown felt hat, turned down brim.” The net was beginning to close around Nelson. Then, he and his crew were linked to a botched roadhouse robbery in Summit, Illinois, on November 23, 1930.In the ensuing gunfight, three people were killed and three wounded. One might think that Nelson would lay low for a while, but three nights later, Nelson’s gang robbed a tavern on Waukegan Road, and Nelson committed his first murder, when he fatally shot stockbroker Edwin R Thompson.

successful, at a mere $4,000. A month later, he and his gang netted $25,000 worth of jewelry from home invasions. On October 3, 1930, Nelson robbed the Itasca State Bank of $4,600…another disappointing take, and an even bigger problem, when a teller later identified him as one of the robbers. Three nights later, he brazenly stole the jewelry of the wife of Chicago mayor Big Bill Thompson, valued at $18,000. She also described her attacker, saying “He had a baby face. He was good looking, hardly more than a boy, had dark hair and was wearing a gray topcoat and a brown felt hat, turned down brim.” The net was beginning to close around Nelson. Then, he and his crew were linked to a botched roadhouse robbery in Summit, Illinois, on November 23, 1930.In the ensuing gunfight, three people were killed and three wounded. One might think that Nelson would lay low for a while, but three nights later, Nelson’s gang robbed a tavern on Waukegan Road, and Nelson committed his first murder, when he fatally shot stockbroker Edwin R Thompson.

Throughout the winter of 1931, most of the “Tape Bandits” were rounded up, including Nelson. The Chicago Tribune referred to their leader as “George ‘Baby Face’ Nelson” who received a sentence of one year to life in the state penitentiary at Joliet. Refusing to be held, Nelson escaped during a prison transfer in February 1932. Through his contacts within the Touhy Gang, Nelson fled west to Reno, where he was harbored by William Graham, a known crime boss and gambler. He began using the alias “Jimmy Johnson” at this point. Nelson…now Johnson went to Sausalito, California, where he worked for bootlegger Joe Parente.

Nelson decided that it was time for him to have a gang of his own after the Grand Haven bank robbery. Nelson used his connections at the Green Lantern Tavern in Saint Paul, to recruit Homer Van Meter, Tommy Carroll, and Eddie Green. With his new gang, and with the addition of two other local thieves, Nelson robbed the First National Bank of Brainerd, Minnesota on October 23, 1933. The take on that robbery was $32,000, or approximately $670,000 in 2021 dollars. It was reported that Nelson wildly sprayed sub-machine gun bullets at bystanders to facilitate his getaway. Then, he picked up his wife, Helen and four-year-old son Ronald, and left with his crew for San Antonio, Texas. In San Antonia, he and his gang bought several weapons from a crooked gunsmith Hyman Lehman, one of which was a .38 Super Colt pistol that had been modified, so it was fully automatic. That gun was used by Nelson to kill Special Agent W Carter Baum at Little Bohemia Lodge several months later.

On December 9, 1933, a local woman tipped off San Antonio police regarding “high-powered Northern gangsters” in the area. Tommy Carroll was cornered two days later by two detectives who opened fire, killing Detective H.C. Perrin and wounding Detective Al Hartman. At that point, the gang split up with all the Nelson gang, except Nelson, leaving San Antonio. As a way to distance himself from the gang, Nelson and his wife traveled west to the San Francisco Bay Area. The prior close call didn’t slow him down, however. In San Francisco, he recruited John Paul Chase and Fatso Negri for a new wave of bank robberies the following spring. The next winter found him in Reno, where he met the vacationing, Alvin Karpis. Karpis introduced him to Midwestern bank robber Eddie Bentz. Teaming up with Bentz, Nelson returned to the Midwest the next summer.  On August 18, 1933, Nelson committed a major bank robbery in Grand Haven, Michigan. It was his first robbery in the area. The robbery was pretty much a failure…but it was a successful failure, because most of those involved made a full escape.

On August 18, 1933, Nelson committed a major bank robbery in Grand Haven, Michigan. It was his first robbery in the area. The robbery was pretty much a failure…but it was a successful failure, because most of those involved made a full escape.

Gillis Helped John Dillinger escape from prison in Crown Point, Indiana, and then became his partner. Nelson and the Touhy Gang were collectively “Public Enemy Number One” by the FBI. The alias, “Baby Face Nelson” came from Gillis being a short man with a youthful appearance. Still, in the professional realm, Gillis’ fellow criminals addressed him as “Jimmy.” On November 27, 1934, FBI agents fatally wounded and killed Baby Face Nelson in the Battle of Barrington, which was fought in a suburb of Chicago, Illinois.