Prior to the Civil War, and even for years afterward, the black man was considered first a non-human, and secondly not very intelligent. Because of that, it was thought that the black soldiers would not be able to handle real combat situations. Nevertheless, the Union Army needed their help, and so they would have to take a chance on the black soldiers along the James River in the spring of 1864. My guess is that it was a rather tense moment when the Federal Soldiers faced off the Rebels on May 24, 1864. They stood behind the walls they had built with their own hands, and watched as the dismounted Rebel cavalry charged toward them. With their rifles trained on the enemy troops, each man knew that this was their chance to prove themselves. They were a brigade of mostly black soldiers, and it was vital that they be able to hold their own against an enemy who outnumbered them two to one. As well as an enemy who was party to their years of slavery.

Prior to the Civil War, and even for years afterward, the black man was considered first a non-human, and secondly not very intelligent. Because of that, it was thought that the black soldiers would not be able to handle real combat situations. Nevertheless, the Union Army needed their help, and so they would have to take a chance on the black soldiers along the James River in the spring of 1864. My guess is that it was a rather tense moment when the Federal Soldiers faced off the Rebels on May 24, 1864. They stood behind the walls they had built with their own hands, and watched as the dismounted Rebel cavalry charged toward them. With their rifles trained on the enemy troops, each man knew that this was their chance to prove themselves. They were a brigade of mostly black soldiers, and it was vital that they be able to hold their own against an enemy who outnumbered them two to one. As well as an enemy who was party to their years of slavery.

The battle the black troops were about to fight was a small part of Lieutenant General Ulysses S Grant’s Overland Campaign. The goal was to cripple the Confederate capital, and in doing so, bring down the Confederacy before the end of 1864. The Army of the James consisted of the X and XVIII Corps. About 40% of the army’s 33,000 men were black. Butler was confident his “colored troops” would do all the Union hoped and more, because he realized they viewed their service as a chance to gain rights they had never had before for themselves and for their families…making blacks free and equal to whites. Of course, fear of capture and a return to slavery, was a great motivator to win this battle and the war too. In early May, Butler and his army left Fort Monroe at the mouth of the James River and drove upriver toward Bermuda Hundred, about 14 miles south of Richmond. The general believed this was a better position to attack the capital from this strip of land, which lies at the point where the Appomattox River meets the James. From there, Butler’s forces could disable rail transportation south of Richmond and with it, communication between the capital and points south.

Late on the afternoon of May 5, a week before the army’s planned arrival on Bermuda Hundred, Butler reported to Grant that Brigadier General Edward A. Wild’s brigade of black troops had captured these two sites without opposition. Their arrival, Butler wrote, was “apparently a complete surprise” to the Confederates. The sight of former slaves coming ashore at Wilson’s Wharf must have almost terrified local planters, because many of the troops had once been held in bondage in the surrounding area. It could feel very intimidating to think of the former slaves motive for revenge. Shortly after the brigade’s arrival, the soldiers captured William Clopton, a wealthy planter known for his brutality. Wild, with his profound hatred of slavery, ordered his men to tie Clopton to a tree and expose his back. Then Wild ordered William Harris of Company E forward to flog his former master, Cheers echoed through the African Brigade. “Mr. Harris played his part conspicuously,” Sergeant Hatton recalled, “bringing the blood from his loins at every stroke, and not forgetting to remind the gentleman of the days gone by.” Wild described the lashing of Clopton to Hinks as “the administration of

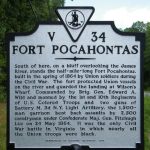

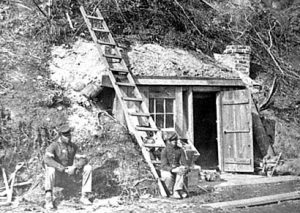

Poetical justice.” The fears of the plantation owners were realized that day, but whipping the planters was the least of Wild’s concerns at Wilson’s Wharf. He immediately put his troops to work on an earthwork fortification on a bluff over the James and named it Fort Pocahontas. The walls held against Confederates, and the Union would go on to win the Civil War, but no one would again be able to say that the black soldiers couldn’t do their job, nor would they ever doubt the depth of their rage over the cruel treatment they had been subjected to by the slave owners.

Poetical justice.” The fears of the plantation owners were realized that day, but whipping the planters was the least of Wild’s concerns at Wilson’s Wharf. He immediately put his troops to work on an earthwork fortification on a bluff over the James and named it Fort Pocahontas. The walls held against Confederates, and the Union would go on to win the Civil War, but no one would again be able to say that the black soldiers couldn’t do their job, nor would they ever doubt the depth of their rage over the cruel treatment they had been subjected to by the slave owners.

Leave a Reply