In 1800, President John Adams approved legislation that appropriated $5,000 to purchase “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” The initial collection of books, ordered from London, arrived in 1801. These were stored in the US Capitol. The books were the library’s first. The inaugural library catalog, dated April 1802, listed 964 volumes and nine maps. The library was President Adams’ pride and joy. In 1814, in what was a largely symbolic maneuver, the British entered Washington DC and burned down the capitol and the library. The fire was dramatic, but really had little relevance, because the city didn’t have an especially large population and, since much of the US government had fled before the British could overtake them, there was little strategic value in the destruction. Nevertheless, the about 3,000 books were lost in that fire.

In 1800, President John Adams approved legislation that appropriated $5,000 to purchase “such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress.” The initial collection of books, ordered from London, arrived in 1801. These were stored in the US Capitol. The books were the library’s first. The inaugural library catalog, dated April 1802, listed 964 volumes and nine maps. The library was President Adams’ pride and joy. In 1814, in what was a largely symbolic maneuver, the British entered Washington DC and burned down the capitol and the library. The fire was dramatic, but really had little relevance, because the city didn’t have an especially large population and, since much of the US government had fled before the British could overtake them, there was little strategic value in the destruction. Nevertheless, the about 3,000 books were lost in that fire.

The Library of Congress must seem like an institution that is unable to be defeated, but the reality is that while it has been there practically forever, acting as the nation’s biggest library, it has been almost destroyed three times. The Library of Congress is one of the largest libraries in the world, with over 170 million items in its collections at present, according to the Library of Congress itself. It possesses a world class collection of rare books and holds the largest known collection of audio recordings, maps, and films, among other materials. It is accessible not only to the Congressional representatives who work nearby in the Capitol, but also to all Americans and members of the public. That was not always the case, however. At its inception, the Library of Congress was for congressional use only.

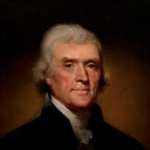

Once the fires of the British died down, they left Washington, and the American lawmakers returned. As has always been the way of Americans, they knew it was time to rebuild. While Congress was putting itself back together, it became clear that most wanted the Library of Congress to return as well. At that point, former president Thomas Jefferson stepped in. He offered to sell his own library to reconstitute the one lost in 1814. It is certainly logical that Jefferson was one proposing such a deal. According to the Library of Congress, he was an avid book reader and lifelong learner with an extensive personal library. While he committed to the notion of an informed, intellectual Congress, Jefferson may have also empathized on a deeper level. In 1770, his own home had burned, and Jefferson, gazing at the ashes, most acutely felt the loss of his books. Later, he would come to possess the largest private library in the United States.

The Library of Congress faced at least three fires in its fight to exist. In fact, its existence as an institution has been challenged numerous obstacles throughout its more than 200 years of existence. The Library of Congress faced space shortages, understaffing, and lack of funding, until the American Civil War increased the importance of legislative research to meet the demands of a growing federal government. Then, in 1870, the library gained the right to receive two copies of every copyrightable work printed in the United States. It also built its collections through acquisitions and donations. Between 1890 and 1897, a new library building, which has now

been renamed the Thomas Jefferson Building, was constructed. Two additional buildings, the John Adams Building (opened in 1939) and the James Madison Memorial Building (opened in 1980), were later added. In total, the Library of Congress has faced major fires at least three times in its history.

been renamed the Thomas Jefferson Building, was constructed. Two additional buildings, the John Adams Building (opened in 1939) and the James Madison Memorial Building (opened in 1980), were later added. In total, the Library of Congress has faced major fires at least three times in its history.

According to the United States House of Representatives, the 1825 fire occurred on the evening of December 22nd. Massachusetts Representative Edward Everett, who was leaving a nearby party, noticed a strange light coming from the library windows. When he informed a Capitol police officer, who did not have a key, Everett dismissed the situation. However, as the glow intensified, it became increasingly difficult to ignore. Eventually, more officers, along with Librarian of Congress George Watterson, discovered the dreadful truth: Library of Congress was on fire…again!!

Both representatives and firefighters fought the blaze, including’s fellow Massachusetts representative, Daniel Webster, and Tennessee politician Sam Houston. They extinguished fire before it spread to the rest of the Capitol. Ultimately, it was determined that the cause was a candle left lit in the room. The damage was not nearly as extensive as the 1814, though some books and a rug were lost.

On December 24, 1851, what is thought to be the most devastating fire destroyed 35,000 books, two-thirds of the library’s collection, and two-thirds of Jefferson’s original transfer. In 1852, Congress appropriated $168,700 to replace the books but not to acquire new materials. By 2008, the librarians of Congress had found replacements for all but 300 of the works documented as being in Jefferson’s original collection. This marked the beginning of a conservative period in the library’s administration under librarian John Silva Meehan and joint committee chairman James A. Pearce, who restricted the library’s activities. Meehan and Pearce’s views on limiting the Library of Congress’s scope were shared by members of Congress. As a librarian, Meehan and perpetuated the notion that “the congressional library should play a limited role on the national scene and its collections, by and large, should emphasize American materials obvious use to the US Congress.” In 1859, Congress transferred the library’s public document distribution activities to the Department of the Interior and its international book exchange program to the Department of State.

These days, the library is open for academic research to anyone with a Reader Identification Card. The library items may not be removed from the reading rooms or the library buildings. Most of the library’s general collection of books and journals are in the closed stacks of Jefferson and Adams Buildings. Specialized collections of books and other materials are in stacks in three main library buildings or stored off-site. Access to the closed stacks not permitted under any circumstances, except to authorized library staff and occasionally to dignitaries. Only reading room reference collections are on open shelves.

Since 1902, American libraries have been able to request books other items through interlibrary loan from the Library of Congress, if these are not available elsewhere. Through this system, the Library of Congress has served as a “library of last resort,” according to former librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam. The Library of Congress lends books to other libraries with the stipulation that they be used only inside the borrowing library. In 2017, the Library of Congress began development of a reader’s card for children under the age of sixteen.

Since 1902, American libraries have been able to request books other items through interlibrary loan from the Library of Congress, if these are not available elsewhere. Through this system, the Library of Congress has served as a “library of last resort,” according to former librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam. The Library of Congress lends books to other libraries with the stipulation that they be used only inside the borrowing library. In 2017, the Library of Congress began development of a reader’s card for children under the age of sixteen.

Leave a Reply