As sometimes happens, children grow up and start hanging out with the wrong crowd. Soon they are in trouble, and it falls to their parents to get them back on the right track. So, what if their parents got them on the wrong track in the first place? Such, it seems was the case with Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, better known as Bonnie and Clyde. No one really knew about the inner workings of Bonnie and Clyde’s gang of thugs. Still, the evidence was mounting, even if the payoffs to the police kept most of that information from getting to the people who needed it.

As sometimes happens, children grow up and start hanging out with the wrong crowd. Soon they are in trouble, and it falls to their parents to get them back on the right track. So, what if their parents got them on the wrong track in the first place? Such, it seems was the case with Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, better known as Bonnie and Clyde. No one really knew about the inner workings of Bonnie and Clyde’s gang of thugs. Still, the evidence was mounting, even if the payoffs to the police kept most of that information from getting to the people who needed it.

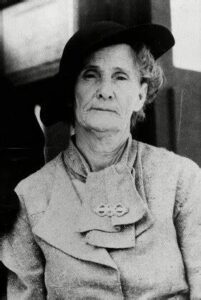

After Bonnie and Clyde, as well as Clyde’s brother Marvin “Buck” Barrow were killed, the US Government began their investigation against most of the Barrow clan, including Clyde Barrow’s mom, Cumie Barrow. In all, more than a dozen family members were put on trial. Strangely, Clyde Barrow’s dad, Henry was not among then. The main focus was on Clyde’s mom, Cumie Barrow. During his closing argument, US attorney for the Northern District of Texas, Clyde O Eastus made a surprising allegation. Pointing at Clyde’s mother, Cumie Barrow, Eastus roared: “She is the ringleader in this conspiracy!” Of course, he was right. I find it odd that she had been given a Hebrew name. If you recall, during one of His miracles, Jesus said to a young girl who had died, “Talitha Cumi” which means “Young girl, arise.” Cumie’s parents turned it around a little and changed the spelling of Cumi to Cumie, but the meaning is still there, just translated “Arise, young girl.” Ironically, Cumie did arise, but it was not to do good, nor was it in any way miraculous, but rather pure evil.

Eastus was probably embellishing his point for the Dallas jury a little bit, by putting Cumie front and center, but he did so because she admitted meeting regularly with the fugitives and was known to provide them with food, clothing and other comforts. Still, when we look back on Bonnie and Clyde’s history, the claims made by Eastus were likely spot on. Cumie was in this a deep as anyone, and especially as deep as Bonnie and Clyde. Reports indicate that Henry and Cumie always lived modestly in their little house, running their service station, and for all intents and purposes not possessing any large amounts of money. It is said that Bonnie and Buck’s wife, Blanche gave some money to their mothers, but the bulk of the money the men stole went to Cumie, to be managed and doled out as needed. It mostly went to the boys and their partners, and to the police, judges, and anyone else that Cumie needed to buy off to save her sons from going to jail. Cumie truly was the woman behind Clyde Barrow.

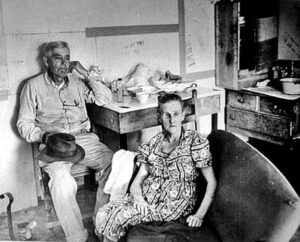

The police and judges in that era were often under paid and under trained, so it was much easier to bribe them, and Cumie would do whatever it took. Cumie worked very hard to paint herself as the loving mother, who was just looking out for her sone. She was almost certainly more complicit than that. Cumie Walker was born near Swift, Texas, in 1874. She married Henry Barrow just after she turned 17. She was far more literate than her husband, who had been sickly and never went to school. The couple started farming, but they were unsuccessful. As their family grew, Cumie became savvy in survival skills. In 1922 they moved to Dallas and Henry began peddling scrap.

In early 1930, he met and fell head over heels for Bonnie Parker, an animated, petite blond who was separated from her teen husband. Just a few weeks later, though, Clyde was arrested and eventually sent to Waco, Texas, where he was quickly tried and convicted for several thefts and burglaries. Authorities in Houston then blamed him for a murder several months before. With Clyde facing 14 years in prison and a murder charge, Cumie gave an interview to the Waco News-Tribune, insisting he was in Dallas, not Houston at the time of the murder. She attributed his troubles to falling in with a bad group of young men and noted, correctly, that he had previously been charged, but never convicted, of a crime. She also told a whopper: “Clyde was just 18 last Monday.” In reality, he was at least two years older than that. Nevertheless, she knew that the state tended to be more lenient with teens, so she did what she had to do. The reality is that he was likely 21.

The murder charge was dropped when another suspect emerged. But when Clyde arrived at the state penitentiary to serve his sentence, he listed his age as 18. Then Cumie told an even bigger lie. She said that her son was needed at home, because she was widowed, and he was needed to help provide for the family. She and Henry had moved their tiny hand-built house to a West Dallas lot where Henry ran a modest filling station from a front room. Henry Barrow was very much alive.

The corruption in those days was definitely cringeworthy. Either Cumie or her lawyers also collected recommendation letters from the sheriff who held Clyde in the Waco jail, the judge who sentenced him, and other officials who supported his release. He should never have been released, and the people he murdered after being released might have lived full lives, had he not been released. Nevertheless, the state pardon board concurred, recommending his parole because “Barrow was only 18 years old when he got into his trouble,” and he would go home to “support and care for” his mother. Of course, Clyde did support his mother, but not by honest means. Within a year, he was linked to at least four murders, some kidnappings, and all kinds of robberies. Still, his mother was quick to defend him, portraying him as “a kind son who came by the gas station just after Christmas to give her a hug and kiss.” She worried aloud that “We may hear any minute that he’s dead.” She claimed that she asked him if he had killed anyone, and he promptly told her, “Mother, I haven’t never done anything as bad as kill a man.” She insisted, “Everybody likes Clyde, you know,” sharing some family photos of her son. Looking at one of them, she sobbed. “Clyde…isn’t a… murderer.”

By July 1933, her son Buck was dying from injuries suffered in two shootouts, including a bullet to his head. Cumie was devastated. She immediately drove with several family members to Iowa. Again, she stood by Clyde, refusing to urge him to turn himself in. She knew that if he surrendered, he would almost certainly be executed. She said, and if he didn’t surrender, officers would likely shoot to kill. “So, I’m going to let him live his last few days the way he wants to.” Bonnie and Clyde were killed on May 23, 1934.

In an early 1935 trial, after closing arguments, the all-male jury found everyone guilty. Even though prosecutor Eastus had condemned Cumie Barrow, the lenient Judge William Atwell struggled to sentence her. Her influence still held firm. Finally, he said, “Perhaps sixty days in jail will suffice.” Then, he asked Cumie, “What do you think of the sentence? Is it fair?” Her eyes red from crying, Cumie looked at him, her hands clasped together. S

he implored, “Judge, won’t thirty days be long enough? I am needed at home.” And in true corruption style, the judge said, “Thirty days in jail.” Cumie died August 14, 1942, at home, after being sick for three or four weeks. She was 67 years old. Of her seven children, Buck and Clyde were dead, two daughters who lived in Dallas had no police records, and the other three were in prison. What a hideous legacy she left.

he implored, “Judge, won’t thirty days be long enough? I am needed at home.” And in true corruption style, the judge said, “Thirty days in jail.” Cumie died August 14, 1942, at home, after being sick for three or four weeks. She was 67 years old. Of her seven children, Buck and Clyde were dead, two daughters who lived in Dallas had no police records, and the other three were in prison. What a hideous legacy she left.

Leave a Reply