Out of necessity, comes innovation. Many of history’s great problems were solved because it was a necessity. For the most part, Britain has maintained a small British Army. Somehow, probably mostly due to geography, rather than might, the British Royal Navy was able to protect the island nation from its enemies quite well…until World War I, that is, and indeed, young men did not feel the need to join the army due to patriotic duty, but rather due to a shortage of other working options. In fact, a career in the military wasn’t looked upon favorably at all.

Out of necessity, comes innovation. Many of history’s great problems were solved because it was a necessity. For the most part, Britain has maintained a small British Army. Somehow, probably mostly due to geography, rather than might, the British Royal Navy was able to protect the island nation from its enemies quite well…until World War I, that is, and indeed, young men did not feel the need to join the army due to patriotic duty, but rather due to a shortage of other working options. In fact, a career in the military wasn’t looked upon favorably at all.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Britain suddenly experienced a huge shortage of trained military personnel, especially officers. This was further complicated by heavy casualties in the British Expeditionary Force in France, which dwindled the limited supply even further. That meant to keep up, they were going to need a large number of officers to be sourced and trained quickly. Their only real solution was to take young upper-class men and put them through officer training. These were teenagers, young men still in school, but it was necessary, and so schooling was either ended or postponed.

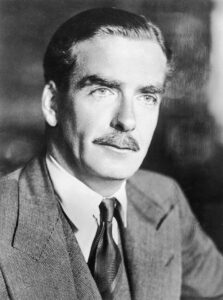

During World War I, as was seen with the RMS Titanic, class was considered of the utmost importance. In Britain, only a gentleman could be an officer. The working-class and lower-class men were put in as the average  soldier. Somehow it was thought that “Short of actual military credentials, a person’s schooling was thought to be a reasonable litmus test for leadership.” To further confuse things in the minds of most Americans these days, a public school in Britain is actually a very exclusive private institution. Eton College, a private institution attended by no fewer than 20 prime ministers, is probably the best example of that. Anthony Eden, who would later become prime minister, was an Eton alum, who also served as an officer in the British Army.

soldier. Somehow it was thought that “Short of actual military credentials, a person’s schooling was thought to be a reasonable litmus test for leadership.” To further confuse things in the minds of most Americans these days, a public school in Britain is actually a very exclusive private institution. Eton College, a private institution attended by no fewer than 20 prime ministers, is probably the best example of that. Anthony Eden, who would later become prime minister, was an Eton alum, who also served as an officer in the British Army.

When World War I broke out, Eden was just 17, and after a rushed officer training course, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant a year later. It seems strange and almost reckless to have upper-class teenagers leading working-class soldiers, but in this case, it actually worked well. The teenage future prime minister recalled his men “were tolerant of me as we were all learning together.” Eden quickly learned that “As long as the officer showed proper concern for the well-being of his men and courage under fire, the men in turn would show great loyalty.”

The commissioned officers were also helped enormously by the noncommissioned officers. The  noncommissioned officers were usually working-class men who had been promoted from the ranks after showing leadership abilities throughout their military careers. Thankfully so, because as Eden would later recall of a sergeant named Arnold Rushworth in his post-war memoirs, “He was my right hand and no small part of my brain as well.” I’m sure that part of the reason this plan of upper-class men becoming officers worked was the sheer compassion of the working-class men, who helped them along the way. It was the way of the times, and I suppose that the men simply accepted their “position” in life as being the way things were, and that it could not be changed.

noncommissioned officers were usually working-class men who had been promoted from the ranks after showing leadership abilities throughout their military careers. Thankfully so, because as Eden would later recall of a sergeant named Arnold Rushworth in his post-war memoirs, “He was my right hand and no small part of my brain as well.” I’m sure that part of the reason this plan of upper-class men becoming officers worked was the sheer compassion of the working-class men, who helped them along the way. It was the way of the times, and I suppose that the men simply accepted their “position” in life as being the way things were, and that it could not be changed.

Leave a Reply