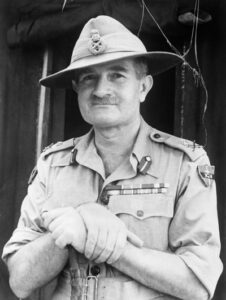

Most of us would never think of using an elephant in a battle, but James Howard Williams, also known as Elephant Bill, who was a British soldier and elephant expert in Burma thought about it. Born on November 15, 1897, at Saint Just, Cornwall, he was the son of a Cornish mining engineer, who had returned to Cornwall from South Africa, and his wife, a Welshwoman. Williams went to college at Queen’s College in Taunton, and following in his brother’s footsteps, studied at Camborne School of Mines. He then went on to serve as an officer in the Devonshire Regiment of the British Army in the Middle East during the First World War and in Afghanistan from 1919 to 1920. Williams served with the Camel Corps and as transport officer in charge of mules. The military was very different then, from what we know today. After his service was over, he decided to join the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation as a forester working with elephants to extract teak logs. Little did he know that this would be a life changing decision for him.

Most of us would never think of using an elephant in a battle, but James Howard Williams, also known as Elephant Bill, who was a British soldier and elephant expert in Burma thought about it. Born on November 15, 1897, at Saint Just, Cornwall, he was the son of a Cornish mining engineer, who had returned to Cornwall from South Africa, and his wife, a Welshwoman. Williams went to college at Queen’s College in Taunton, and following in his brother’s footsteps, studied at Camborne School of Mines. He then went on to serve as an officer in the Devonshire Regiment of the British Army in the Middle East during the First World War and in Afghanistan from 1919 to 1920. Williams served with the Camel Corps and as transport officer in charge of mules. The military was very different then, from what we know today. After his service was over, he decided to join the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation as a forester working with elephants to extract teak logs. Little did he know that this would be a life changing decision for him.

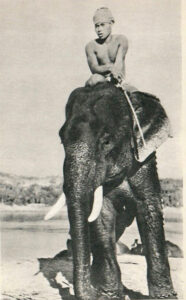

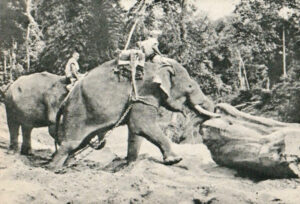

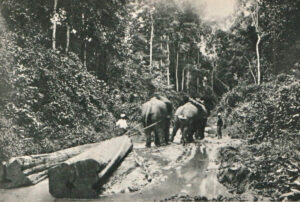

Williams learned so much about the elephants in Burma, that it was during that time he acquired his nickname, “Elephant Bill.” While his biggest calling was his work with the Fourteenth Army during the Burma Campaign of World War II, he was also known for his 1950 book Elephant Bill. He was made a Lieutenant-Colonel, mentioned in dispatches three times, and was awarded the OBE in 1945. His interest in elephants came after he read a book by Hawkes, called “The Diseases of the Camel and the Elephant” and decided on the postwar job in Burma. Initially he was at a camp on the banks of the Upper Chindwin River in Upper Burma. There, Williams was responsible for seventy elephants and their oozies (in Burma an oozie was an elephant trainer) in ten camps, in an area of about 400 square miles in the Myittha Valley, in the Indaung Forest Reserve. The camps were 6 to 7 miles apart. Between the camps were hills, three to four thousand feet high and filled with teak. To mill them, one tree was killed by ring-barking the base, and then felled. The three-year-old trees were mature and were now light enough to float. The logs were hauled by elephant (known as “sappers”) to a waterway, then floated down to Rangoon or Mandalay. The elephants were needed by the Royal Engineers for use in bridge building in places where heavy equipment could otherwise not be brought in, the Royal Indian Army Service Corps wanted them to be regarded simply as a branch of transport, but they also had great value in rescue. Elephants were so important to the harvesting process, that one elephant could be sold for $150,000, which is $2000 in American dollars. The elephants were as big a commodity as the teak wood. Believe it or not, teak was “as important a munition of war as steel,” so its extraction was an essential industry.

While elephants were most often used to extract the teak from the forests, they were used for another important extraction during World War II. When Japan entered the war, it was expected that they would be held in Malaya and Singapore. While many people were critical of them, the Bombay Burma Corporation arranged evacuation of European women and children, even though the government had no such plans. That evacuation took place in 1942, from February till the end of April. The retreat from Burma was to Assam via Imphal. The road to Assam went up the Chindwin to Kalewa, then up the Kabaw Valley to Tamu, and across five thousand-foot-mountains into Manipur and the Imphal Plain. During this time, Williams was attached to one evacuation party, which also included his wife and children. The Kabaw Valley was nicknamed “The Valley of Death” because of the hundreds of refugees who died there from exhaustion, starvation, cholera, dysentery, and smallpox. Nevertheless, while many people died along the way, many were also saved due to the elephant evacuation process. The well known “elephant whisperer” and his best beloved helpers waged guerrilla warfare and carried refugees to safety. They sometimes had to fight, possibly even while working to help the refugees to escape. He was a Burmese speaker with knowledge of Burma, including the Irrawaddy River area and jungle tracks, which gave him a distinct edge when it came to getting precious human cargo out of the danger zones.

Not all treatment of elephants during that time was humane, and many elephants that were captured by the Japanese, and later recaptured by Williams’ group and others like it, had to be “cured” after being attacked by Allied fighters when they were used in Japanese warfare, or treated for acid burns from wireless batteries carried on their backs in straw-lined boxes. I’m sure it was hard for the handlers to see their precious elephants

after such treatment. After World War II Williams retired to Saint Buryan, Cornwall, as an author and market gardener. He married Susan Margaret Rowland in 1932 after they met in Burma; they had a son, Treve and daughter, Lamorna while in Burma. After his death, on July 30, 1958, his wife Susan Williams wrote of her life with him in “The Footprints of Elephant Bill.”

after such treatment. After World War II Williams retired to Saint Buryan, Cornwall, as an author and market gardener. He married Susan Margaret Rowland in 1932 after they met in Burma; they had a son, Treve and daughter, Lamorna while in Burma. After his death, on July 30, 1958, his wife Susan Williams wrote of her life with him in “The Footprints of Elephant Bill.”

Leave a Reply