Rain…most often a welcome sight, especially during the hot summer months, and sometimes early fall months too. The Casper, Wyoming area is not one to get a lot of rain, however. Nevertheless, the rain had been coming down heavily for a week, that late September of 1923. In fact there had been three straight days of downpour. The railroad personnel were keeping a close eye on the rivers, creeks, and bridges. They were concerned, but did not expect the volatile, and possibly catastrophic situation that could be heading their way. Cole Creek was reported to have less than 16 inches of rainwater in its bed and by 8pm on September 27th, and the bridge was believed secure. Hours later, the water level would reportedly rise two feet in half an hour.

Rain…most often a welcome sight, especially during the hot summer months, and sometimes early fall months too. The Casper, Wyoming area is not one to get a lot of rain, however. Nevertheless, the rain had been coming down heavily for a week, that late September of 1923. In fact there had been three straight days of downpour. The railroad personnel were keeping a close eye on the rivers, creeks, and bridges. They were concerned, but did not expect the volatile, and possibly catastrophic situation that could be heading their way. Cole Creek was reported to have less than 16 inches of rainwater in its bed and by 8pm on September 27th, and the bridge was believed secure. Hours later, the water level would reportedly rise two feet in half an hour.

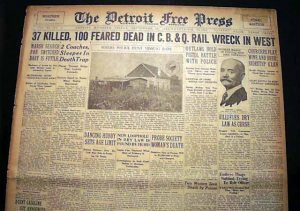

On September 27, 1923, The Chicago Burlington and Quincy Number 30 passenger train left Casper for Denver at approximately 8:30pm with approximately 60-70 passengers on board. the exact number is unknown. The train reached Cole Creek by 9:15pm and approached the Cole Creek bridge shortly after. Unexpectedly, Number 30 attempted to slow, and eventually braked upon realizing the usually dry gully below was now a torrent of rushing water and vision was severely limited. It is unknown if the rushing water was unnerving or if they saw something of the impending disaster through the rain, but they did attempt to slow down. Unfortunately, the bridge’s trestle had already been washed out or badly weakened. The realization of the situation came too late for the crew of CBQ number 30.

The 100-ton locomotive engine and first five, of seven train cars plummeted into the sand and water below. Most of the passengers were in two of these cars. Ans the cars hit, metal crunched, windows and doors burst under flood of water, steam from the engine scalded passengers and worse, and it would take more than an hour for help to arrive, especially when the first call to the Casper dispatcher’s office didn’t come for 45 minutes. From that point, the city sprang into action. Emergency news alerts calling for doctors and volunteers flashed across movie screens in town. The residents first thought it was a refinery disaster…which was much more expected here than a train wreck. Instead, however, they were faced with the greatest train wreck in Wyoming’s history, as it would come to be known.

Try as they might, rescue crews could do very little until the following morning. At first, bodies were found washed down the North Platte River for hundreds of yards, but they would eventually reach miles down the river. The massive recovery efforts would continue for weeks. The cleanup ended October 15, still daily reports were provided by local newspapers and radio. There were still people missing, but winter was upon them, and anyone who lives near the Platte River, or it’s tributaries, knows that once the ice sets in, bodies remain hidden  beneath the surface.

beneath the surface.

The body of the train’s conductor, Guy Goff, was found seven months later, in May 1924, washed down the North Platte. Engineer, Ed Spangler, was discovered in January of the following year. In all, the cost of the wreck totaled close to a million dollars and 31 deaths are reported, although the final number remains uncertain because of the discrepancy in passenger numbers. The day after the wreck, a nine-year-old boy was seen searching for days for his father at the wreck site. No confirmation was received that the man was ever found.

Leave a Reply