With summer, and especially late summer, when things are beginning to dry up, comes an increased danger of wildfires. Add to that, an extremely dry spring and early summer, and you have a recipe for disaster. Such was the case in northwest Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana in 1910. There were a great number of problems that contributed to an over active fire season, and ultimately, the destruction that began on August 20, 1910, quickly became a firestorm that burned about three million acres…a full 4,700 square miles before it was over. The areas burned included parts of the Bitterroot, Cabinet, Clearwater, Coeur d’Alene, Flathead, Kaniksu, Kootenai, Lewis and Clark, Lolo, and Saint Joe National Forests. The extensive burned area was approximately the size of the state of Connecticut. The extreme scorching heat of the sudden blowup can be attributed to the great Western White Pine forests that blanketed Idaho. The hydrocarbons in the resinous sap boiled out and created a cloud of highly flammable gas that blanketed hundreds of square miles, which then spontaneously detonated dozens of times, each time sending tongues of flame thousands of feet into the sky, and creating a rolling wave of fire that destroyed anything and everything in its path.

With summer, and especially late summer, when things are beginning to dry up, comes an increased danger of wildfires. Add to that, an extremely dry spring and early summer, and you have a recipe for disaster. Such was the case in northwest Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana in 1910. There were a great number of problems that contributed to an over active fire season, and ultimately, the destruction that began on August 20, 1910, quickly became a firestorm that burned about three million acres…a full 4,700 square miles before it was over. The areas burned included parts of the Bitterroot, Cabinet, Clearwater, Coeur d’Alene, Flathead, Kaniksu, Kootenai, Lewis and Clark, Lolo, and Saint Joe National Forests. The extensive burned area was approximately the size of the state of Connecticut. The extreme scorching heat of the sudden blowup can be attributed to the great Western White Pine forests that blanketed Idaho. The hydrocarbons in the resinous sap boiled out and created a cloud of highly flammable gas that blanketed hundreds of square miles, which then spontaneously detonated dozens of times, each time sending tongues of flame thousands of feet into the sky, and creating a rolling wave of fire that destroyed anything and everything in its path.

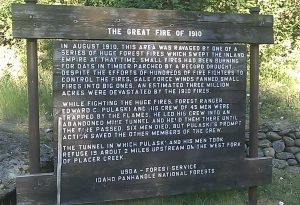

That summer had been described as “like no others.” The drought resulted in forests that were filled with dry fuel, which had previously grown up on abundant autumn and winter moisture. Fires were set by hot cinders flung from locomotives, sparks, lightning, and backfiring crews, and by mid-August, there were 1,000 to 3,000 fires burning in Idaho, Montana, Washington, and British Columbia. Then on August 20th, everything blew up into a firestorm. The firestorm burned over two days, August 20 and 21. It killed 87 people, most of them firefighters. The entire 28 man “Lost Crew” was overcome by flames and perished on Setzer Creek in Idaho outside of Avery. The Great Fire of 1910 is believed to be the largest, although not the deadliest, forest fire in United States history. It was commonly referred to as the Big Blowup, the Big Burn, or the Devil’s Broom fire. Smoke from the fire could be seen as far east as Watertown, New York, and as far south as Denver, Colorado. It was reported that at night, five hundred miles out into the Pacific Ocean, ships could not navigate by the stars because the sky was cloudy with smoke.

The fire actually started as many small fires. Then, on August 20, a cold front blew in and brought hurricane-force winds. The wind whipped the hundreds of small fires into one or two blazing infernos. The larger fires were impossible to fight. They simply didn’t have the manpower, or the supplies. The United States Forest Service…then called the National Forest Service…was only five years old at the time and unprepared for the possibilities of this dry summer. Later, at the urging of President William Howard Taft, the United States Army, 25th Infantry Regiment…known as the Buffalo Soldiers, was brought in to help fight the blaze. The most famous story of survival was that of Ed Pulaski, a United States Forest Service ranger who led a large group of his men to safety in an abandoned prospect mine outside of Wallace, Idaho, just as they were about to be overtaken by the fire. Pulaski fought off the flames at the mouth of the shaft until he passed out like the other men. Around midnight, one man said that he was getting out of there. Knowing that they would have no

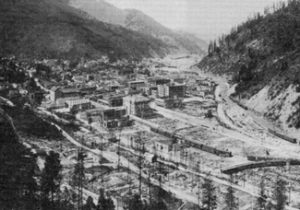

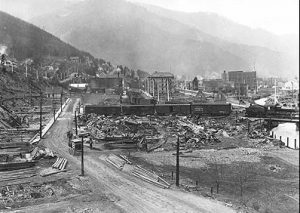

chance of survival if they ran, Pulaski drew his pistol. He threatened to shoot the first person who tried to leave. In the end, all but five of the forty or so men survived. Several towns were completely destroyed by the fire. The fire was finally extinguished when another cold front swept in, bringing with it, steady rain. Unfortunately, it was too late for the 87 people who lost their lives in the blaze. Memorials were placed in several of the fire areas.

chance of survival if they ran, Pulaski drew his pistol. He threatened to shoot the first person who tried to leave. In the end, all but five of the forty or so men survived. Several towns were completely destroyed by the fire. The fire was finally extinguished when another cold front swept in, bringing with it, steady rain. Unfortunately, it was too late for the 87 people who lost their lives in the blaze. Memorials were placed in several of the fire areas.

Leave a Reply