west virginia

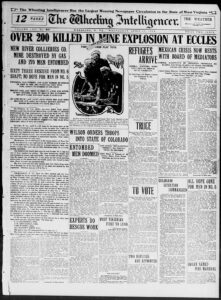

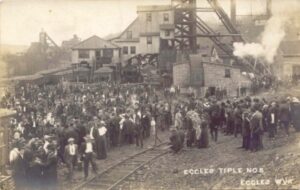

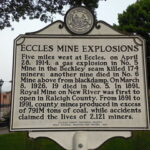

If you lived in Eccles, West Virginia in 1914, you or someone in your family most likely worked at the Eccles Mine Number 5. Eccles was a tiny town in Raleigh County. Mine number 5 was opened in 1905, and by 1914, the mine employed most of the local men and even the teenagers. Life was mundane for the most part. Not much happened in the town, and April 28, 1914 promised to be just another boring day. On that Tuesday morning, dozens of local men and teens left their homes to go to work at the Eccles Mine Number 5, which was one of group of coal mines in West Virginia owned by the New River Colliers Company. Everything was going along fine, when suddenly, at 2:30pm, a sudden explosion rocked the Number 5 mine. In an instant, more than 180 workers who had left home as usual that day, would never go home again.

If you lived in Eccles, West Virginia in 1914, you or someone in your family most likely worked at the Eccles Mine Number 5. Eccles was a tiny town in Raleigh County. Mine number 5 was opened in 1905, and by 1914, the mine employed most of the local men and even the teenagers. Life was mundane for the most part. Not much happened in the town, and April 28, 1914 promised to be just another boring day. On that Tuesday morning, dozens of local men and teens left their homes to go to work at the Eccles Mine Number 5, which was one of group of coal mines in West Virginia owned by the New River Colliers Company. Everything was going along fine, when suddenly, at 2:30pm, a sudden explosion rocked the Number 5 mine. In an instant, more than 180 workers who had left home as usual that day, would never go home again.

The explosion was caused by coal-seam methane. At least 180 men lay dead, at least that was the death roll published as of 2011 by the National Coal Heritage Trail. A monument at the cemetery lists 183 victims, and  the records of the county coroner list 186. When the mine was rocked by a series of violent explosions, parts of the mine collapsed while other parts were heavily damaged, which trapped the miners inside. Of course, the people of Eccles and officials from the mining company rushed to the scene to aid the rescue efforts. Despite their best efforts, it was soon obvious that this would be a recovery effort, and not a rescue. That day, all of the miners in Eccles Mine Number 5 were killed, including five who were under the age of 14 years of age. In addition, nine workers in a nearby mine were killed when deadly gas from Mine Number 5 seeped into their mine. Ironically, one of the men who died in the nearby mine, was an insurance agent from Charleston, West Virginia, who had only gone into the mine to solicit business from the men. He was only there for a few minutes. It was there that the salesman, who had unfortunately chosen that day to visit the mine and sell insurance to its workers, was also killed. The blast and the subsequent damage to the mine, left many of the victim so mangled and torn apart, that most of them could not be positively identified because of their horrific injuries.

the records of the county coroner list 186. When the mine was rocked by a series of violent explosions, parts of the mine collapsed while other parts were heavily damaged, which trapped the miners inside. Of course, the people of Eccles and officials from the mining company rushed to the scene to aid the rescue efforts. Despite their best efforts, it was soon obvious that this would be a recovery effort, and not a rescue. That day, all of the miners in Eccles Mine Number 5 were killed, including five who were under the age of 14 years of age. In addition, nine workers in a nearby mine were killed when deadly gas from Mine Number 5 seeped into their mine. Ironically, one of the men who died in the nearby mine, was an insurance agent from Charleston, West Virginia, who had only gone into the mine to solicit business from the men. He was only there for a few minutes. It was there that the salesman, who had unfortunately chosen that day to visit the mine and sell insurance to its workers, was also killed. The blast and the subsequent damage to the mine, left many of the victim so mangled and torn apart, that most of them could not be positively identified because of their horrific injuries.

In the early 1900s, coal was in great demand. Production in the United States had increased from 50 million tons of coal in 1850 to 250 million tons of coal in 1903. Unfortunately, the increasing demand and the rush to supply, brought with it worsening work conditions. The danger occurred when the men were digging for coal in deep mines, in which chambers of gas lay just underneath. That meant that highly explosive gasses could come into contact with carbide headlamps. The next thing they knew, they had an explosion on their hands. The mine

disaster brought attention to an overall safety problem in the West Virginia mining industry. Sadly…at least in that it didn’t happen sooner, the disaster actually aided the unions’ attempts to improve the workers’ conditions. The labor union helped to ban carbide headlamps in West Virginia. It was suspected that the headlamps were most likely the cause of the Eccles explosion, as well as a second mine explosion 18 years later in Illinois.

disaster brought attention to an overall safety problem in the West Virginia mining industry. Sadly…at least in that it didn’t happen sooner, the disaster actually aided the unions’ attempts to improve the workers’ conditions. The labor union helped to ban carbide headlamps in West Virginia. It was suspected that the headlamps were most likely the cause of the Eccles explosion, as well as a second mine explosion 18 years later in Illinois.

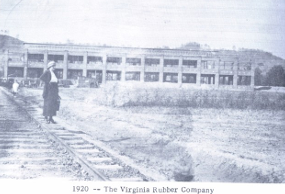

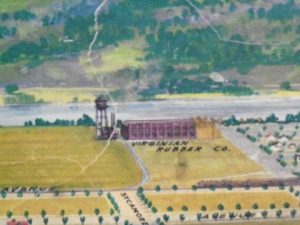

Several hundred people were employed by the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company in Saint Albans, West Virginia, on January 13, 1924. The business, located on 41 acres of land along the Kanawha River across from the present-day Ordnance Park (ca. 1941)…and before MacCorkle Avenue, was thriving in 1924. Established in 1920, it was only four years old. Unfortunately, the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company, was destined not to reach it’s fifth year. That fateful January day in 1924, brought with it a fire that destroyed the company, causing damage totaling $500,000.

Several hundred people were employed by the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company in Saint Albans, West Virginia, on January 13, 1924. The business, located on 41 acres of land along the Kanawha River across from the present-day Ordnance Park (ca. 1941)…and before MacCorkle Avenue, was thriving in 1924. Established in 1920, it was only four years old. Unfortunately, the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company, was destined not to reach it’s fifth year. That fateful January day in 1924, brought with it a fire that destroyed the company, causing damage totaling $500,000.

While I was unable to find much information as to the time and cause of the fire, it is noted that only about 10 percent of the tire stock was saved, and the rest was burned. That isn’t really surprising, since rubber tires are highly flammable. Unfortunately, it also doesn’t appear that all of the loss was covered by the company’s insurance. As an insurance agent, I can say that a property loss that was not completely covered by insurance could only mean that the company was underinsured, leaving gaps in the coverage. What is known about the loss is that the unpaid portion was enough to ensure that the company could never open their doors again. That meant that several hundred people were out of a job, and while they didn’t know it, the Great Depression was coming up quickly. I’m sure they all had jobs before that time, but it was quite likely that they would lose their jobs when that  time came.

time came.

The good news about the fire was that it took no lives. The only loss was to the property. Nevertheless, the town would never be quite the same again. Other businesses would grow up where the rubber company had once been, but mostly it would be remembered as the site of Morgan’s Plantation Kitchen, originally established in 1846. I supposed the site went back to it’s former identity. Still, the total loss of the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company, manufacturer of tires, tubes, toy balloons, balls, and rubber dolls, would not be forgotten.

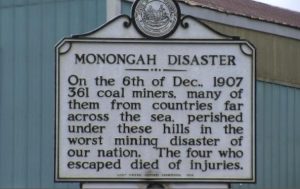

Coal mining, especially underground coal mining can be a dangerous occupation. No matter how hard the safety coordinators tried to keep people safe, and no matter how stringent the safety regulations were, accidents happened and sometimes, lives were lost. Coal mining was especially dangerous when coal dust ignited. Explosions were the main cause of death in the mines,especially the underground mines. And that was just the instantaneous death. Breathing the dust caused a slow death over time. In 1883, the creation of the Norfolk and Western Railway opened a gateway to the untapped coalfields of southwestern West Virginia. New mining towns sprung up in the region practically overnight, with European immigrants and African Americans from the south pouring into southern West Virginia looking for work in the new industry. By the late 19th century, West Virginia was a national leader in the production of coal,but the state fell far behind other major coal-producing states in regulating the mining conditions. In addition to poor economic conditions, West Virginia had a higher mine death rate than any other state. Nationwide, a total of 3,242 Americans were killed in mine accidents in 1907, but no one accident could compare to the accident that was about to unfold as the year neared its end. No on was prepared for the horror that was to come in Monongah in December.

Coal mining, especially underground coal mining can be a dangerous occupation. No matter how hard the safety coordinators tried to keep people safe, and no matter how stringent the safety regulations were, accidents happened and sometimes, lives were lost. Coal mining was especially dangerous when coal dust ignited. Explosions were the main cause of death in the mines,especially the underground mines. And that was just the instantaneous death. Breathing the dust caused a slow death over time. In 1883, the creation of the Norfolk and Western Railway opened a gateway to the untapped coalfields of southwestern West Virginia. New mining towns sprung up in the region practically overnight, with European immigrants and African Americans from the south pouring into southern West Virginia looking for work in the new industry. By the late 19th century, West Virginia was a national leader in the production of coal,but the state fell far behind other major coal-producing states in regulating the mining conditions. In addition to poor economic conditions, West Virginia had a higher mine death rate than any other state. Nationwide, a total of 3,242 Americans were killed in mine accidents in 1907, but no one accident could compare to the accident that was about to unfold as the year neared its end. No on was prepared for the horror that was to come in Monongah in December.

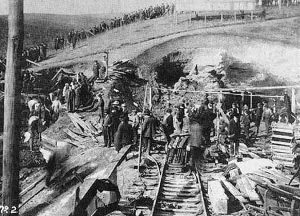

The worst mining accident in United States occurred on December 6, 1907. The mine was the Monongah Coal  Mine in West Virginia’s Marion County. on that date, an explosion in a network of mines owned by the Fairmont Coal Company in Monongah killed 362 coal miners. Officially, there were 367 men in the two mines, but the actual number was much higher because officially registered workers often took their children and other relatives into the mine to help. No one thought of the practice as dangerous. At 10:28am an explosion occurred that killed most of the men inside the mine instantly. The blast went on to cause considerable damage to both the mine and the surface. The ventilation systems, necessary to keep fresh air supplied to the mine, were destroyed along with many rail cars and other equipment. The explosion blew the timbers supporting the roof down causing further issues when the roof collapsed. Investigators believed that an electrical spark or one of the miners’ open flame lamps ignited coal dust or methane gas, but the cause of the explosion was not determined.

Mine in West Virginia’s Marion County. on that date, an explosion in a network of mines owned by the Fairmont Coal Company in Monongah killed 362 coal miners. Officially, there were 367 men in the two mines, but the actual number was much higher because officially registered workers often took their children and other relatives into the mine to help. No one thought of the practice as dangerous. At 10:28am an explosion occurred that killed most of the men inside the mine instantly. The blast went on to cause considerable damage to both the mine and the surface. The ventilation systems, necessary to keep fresh air supplied to the mine, were destroyed along with many rail cars and other equipment. The explosion blew the timbers supporting the roof down causing further issues when the roof collapsed. Investigators believed that an electrical spark or one of the miners’ open flame lamps ignited coal dust or methane gas, but the cause of the explosion was not determined.

Time was of the essence to bring people out of a mine accident alive, because at that time they didn’t know much about restoring the air supply to the people trapped below. The first volunteer rescuers entered the two mines 25 minutes after the initial explosion. The biggest threats to rescuers are the various fumes, particularly “blackdamp”, a mix of carbon dioxide and nitrogen that contains no oxygen, and “whitedamp”, which is carbon monoxide. The lack of breathing apparatus at the time made venturing into these areas impossible. Rescuers could only stay in the mine for 15 minutes at a time. In a vain effort to protect themselves, some of the miners  tried to cover their faces with jackets or other pieces of cloth. While this may filter out particulate matter, it would not protect the miners in an oxygen-free environment. The toxic fume problems were compounded by the infrastructural damage caused by the initial explosion…mines require large ventilation fans to prevent toxic gas buildup, and the explosion at Monongah had destroyed all of the ventilation equipment. The inability to clear the mine of gases transformed the rescue effort into a recovery effort. One Polish miner was rescued and four Italian miners escaped. Following the accident, the United Mine Workers of America labor union and sympathetic legislators forced safety regulations that brought a steady decline in death rates in West Virginia and elsewhere.

tried to cover their faces with jackets or other pieces of cloth. While this may filter out particulate matter, it would not protect the miners in an oxygen-free environment. The toxic fume problems were compounded by the infrastructural damage caused by the initial explosion…mines require large ventilation fans to prevent toxic gas buildup, and the explosion at Monongah had destroyed all of the ventilation equipment. The inability to clear the mine of gases transformed the rescue effort into a recovery effort. One Polish miner was rescued and four Italian miners escaped. Following the accident, the United Mine Workers of America labor union and sympathetic legislators forced safety regulations that brought a steady decline in death rates in West Virginia and elsewhere.

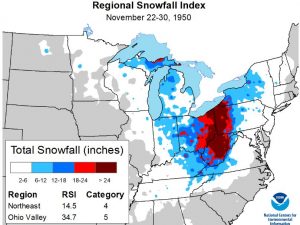

As winter arrived in Coburn Creek, West Virginia in 1950, a storm of epic proportions was about to set some serious records. From November 22 to 30, a slow-moving, powerful storm system dumped heavy snow across much of the central Appalachians. The storm would be remembered as as “The Great Appalachian Storm of 1950,” and it blanketed areas from western Pennsylvania southward deep into West Virginia with over 30 inches of snow. Several locations even received more than 50 inches of snow. Coburn Creek, West Virginia, reported the greatest snowfall total…a staggering 62 inches. Most towns can be shut own with 24 inches, so 62 inches was unthinkable. There is no way a car can get through that, in fact it will take hours to get a snowplow through it. For all intents and purposes, much of the Appalachian Mountains, and especially the Coburn Creek area were at a standstill.

As winter arrived in Coburn Creek, West Virginia in 1950, a storm of epic proportions was about to set some serious records. From November 22 to 30, a slow-moving, powerful storm system dumped heavy snow across much of the central Appalachians. The storm would be remembered as as “The Great Appalachian Storm of 1950,” and it blanketed areas from western Pennsylvania southward deep into West Virginia with over 30 inches of snow. Several locations even received more than 50 inches of snow. Coburn Creek, West Virginia, reported the greatest snowfall total…a staggering 62 inches. Most towns can be shut own with 24 inches, so 62 inches was unthinkable. There is no way a car can get through that, in fact it will take hours to get a snowplow through it. For all intents and purposes, much of the Appalachian Mountains, and especially the Coburn Creek area were at a standstill.

The cold front was massive, with frigid air stretching from the Northeast into the Ohio Valley and all the way down into the far Southeast. Temperatures fell to 22°F in Pensacola, Florida, 5°F in Birmingham, Alabama, 3°F in Atlanta, Georgia, and 1°F in Asheville, North Carolina. This record cold led to widespread crop damage, particularly in Georgia and South Carolina. In the north, intense winds associated with the storm caused extensive tree damage, power outages, and coastal flooding in New England. In New Hampshire, Mount Washington observed gusts as high as 160 mph. And, onshore winds along the coast caused extreme high tides and flooding in New Jersey and Connecticut. The storm was fairly short lived, and the temperatures quickly returned to normal in the first week of December 1950, bringing a whole new problem with them. The rise in temperatures led to a fast snowmelt, flooding several tributaries and major rivers. The Ohio River reached 28.5 feet, 4 feet above flood stage, in Pittsburgh. In Cincinnati, it reached 56 feet, also 4 feet above flood stage.

At the time, the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950 was one of the costliest storms on record, and it contributed to at least 160 deaths. Overall, on the Regional Snowfall Index (RSI) this powerful storm ranked as a Category 5…the worst category, for the Ohio Valley, and a Category 4 for the Northeast of the 212 storms our scientists have analyzed for the region. The RSI value of 34.7 securely locks its first place rank, well above the 24.6 RSI value second worst storm in March 1993. Only four Category 5 storms have impacted the Ohio Valley since 1900, so it is highly uncommon. During the storm, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, received 30.2 inches of snow, and both Erie, Pennsylvania, and Youngstown, Ohio, received more than 28 inches of snow. Across the region, over 18 inches of snow affected more than 6.1 million people. Such high snowfall totals affecting so many people largely contributed to the storm’s high ranking on the RSI scale.

In the Northeast region, the Great Appalachian Storm ranks as the ninth worst storm to impact the area out of the 203 analyzed. That fact seems surprising given the severity of the storm. I would have expected a much higher ranking. Over 30 inches of snow affecting 1.3 million people in the region largely contributed to the regional RSI value of 14.5. With that value, it ranks just behind the more recent February 2003, February 2010, and January 2016 storms. The late February snowstorm of 1969 remains the strongest storm to hit the

Northeast, with an RSI value of 34.0 making it a Category 5 or “Extreme” event. The March 1993 “Storm of the Century” remains the second strongest snowstorm to hit the Northeast, with an RSI value of 22.1 also making it a Category 5 event. As I look out my window at the light snow falling, I find myself feeling grateful that this storm is not expected to be anything like the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950.

Northeast, with an RSI value of 34.0 making it a Category 5 or “Extreme” event. The March 1993 “Storm of the Century” remains the second strongest snowstorm to hit the Northeast, with an RSI value of 22.1 also making it a Category 5 event. As I look out my window at the light snow falling, I find myself feeling grateful that this storm is not expected to be anything like the Great Appalachian Storm of 1950.

Tornado warnings and warning sirens are things that just about every person knows about these days, but in 1944, they weren’t available at all. It wasn’t that no one had thought about a tornado warning system, but rather that they had and they decided against it,and so nothing was developed. If you’re like me, you wonder why anyone would think it a bad idea to warn people about the possibility of a tornado, but that was exactly what happened. According to a report titled “The History (and Future) of Tornado Warning Dissemination in the United States” by Timothy A. Coleman, Kevin R. Knupp, James Spann, J. B. Elliott, and Brian E. Peters, “Despite promising research on the conditions that are favorable for tornadoes in the 1880s by John P. Finley, a general consensus was reached among scientists in the 1880s and 1890s that tornado forecasts and warnings would cause more harm than good. A ban was placed on the issuance of tornado warnings from 1887, when the U.S. Army Signal Corps handled weather forecasts, until 1938, when the civilian U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) finally lifted the ban.” Even after the an was lifted, warnings were pretty primitive. Modern tornado warning really took off and began to develop in 1948…too late for the people of West Virginia and Pennsylvania on June 23, 1944.

Tornado warnings and warning sirens are things that just about every person knows about these days, but in 1944, they weren’t available at all. It wasn’t that no one had thought about a tornado warning system, but rather that they had and they decided against it,and so nothing was developed. If you’re like me, you wonder why anyone would think it a bad idea to warn people about the possibility of a tornado, but that was exactly what happened. According to a report titled “The History (and Future) of Tornado Warning Dissemination in the United States” by Timothy A. Coleman, Kevin R. Knupp, James Spann, J. B. Elliott, and Brian E. Peters, “Despite promising research on the conditions that are favorable for tornadoes in the 1880s by John P. Finley, a general consensus was reached among scientists in the 1880s and 1890s that tornado forecasts and warnings would cause more harm than good. A ban was placed on the issuance of tornado warnings from 1887, when the U.S. Army Signal Corps handled weather forecasts, until 1938, when the civilian U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) finally lifted the ban.” Even after the an was lifted, warnings were pretty primitive. Modern tornado warning really took off and began to develop in 1948…too late for the people of West Virginia and Pennsylvania on June 23, 1944.

On that June 23rd in 1944, a series of tornadoes across West Virginia and Pennsylvania kill more than 150 people. Most of the twisters were classified as F3, but the most deadly one was an F4 on the Fujita scale, meaning it was a devastating tornado, with winds in excess of 207 miles per hour. The afternoon was very hot, when atmospheric conditions suddenly changed and the tornadoes began to form in Maryland. At about 5:30 pm, an F3 tornado, with winds between 158 and 206 miles per hour, struck in western Pennsylvania. That storm killed two people. Just Forty-five minutes later, a very large twister began in West Virginia, and moved into Pennsylvania. It then tracked back to West Virginia. By the time this F4 tornado ended, it had killed 151 people and leveled hundreds of homes. Another tornado struck that afternoon at a YMCA camp in Washington, Pennsylvania. A letter written by a camper was later found 100 miles away. Area Coal-mining towns were also hit hard on June 23rd. There were some reports that a couple of tornadoes actually crossed the Appalachian mountain range, going up one side and coming down the other…a very rare event with any mountain. Finally, about 10 pm, the remarkable series of twisters finally ended, after the last one hit in Tucker County, West Virginia. In all, the storms caused the  destruction of thousands of structures and millions of dollars in damages, and that was just the monetary losses.

destruction of thousands of structures and millions of dollars in damages, and that was just the monetary losses.

While there isn’t much that can be done to spare property in the path of tornadoes, an early warning, and the appropriate action taken, can save the lives of hundreds of people. Sadly, early warnings were not available to save the 153 people killed in the tornado outbreak of June 23, 1944. They were still in the works, because of all the years wasted when scientists decided it was not in the public’s best interest to know about tornadoes. I’m really thankful that the ban was lifted and we have these necessary warnings these days.

When a disaster strikes, we often see whole cities affected by the event. Rebuilding takes years, and the emotional scars might never heal. Plane crashes, while a disastrous event, seldom affect an entire town, not even if the plane crashed in the town. Those affect the people who saw the crash, rushed in to help the survivors, and cleaned up the aftermath…usually. That was not the case on November 14, 1970, when a charter plane carrying most of the Marshall University football team clipped a stand of trees and crashed into a hillside just two miles from the Tri-State Airport in Kenova, West Virginia. The team was returning from that day’s game, a 17-14 loss to East Carolina University. The investigators found that the plane was to the right of the correct approach corridor, and that is why they clipped the trees. Nevertheless, the plane crashed killing thirty seven Marshall football players, the team’s coach, its doctors, the university athletic director and 25 team boosters members, who were some of Huntington, West Virginia’s most prominent citizens, and had traveled to North Carolina to cheer on the Thundering Herd. One of the citizens of the town of Huntington later wrote that “the whole fabric, the whole heart of the town was aboard.”

When a disaster strikes, we often see whole cities affected by the event. Rebuilding takes years, and the emotional scars might never heal. Plane crashes, while a disastrous event, seldom affect an entire town, not even if the plane crashed in the town. Those affect the people who saw the crash, rushed in to help the survivors, and cleaned up the aftermath…usually. That was not the case on November 14, 1970, when a charter plane carrying most of the Marshall University football team clipped a stand of trees and crashed into a hillside just two miles from the Tri-State Airport in Kenova, West Virginia. The team was returning from that day’s game, a 17-14 loss to East Carolina University. The investigators found that the plane was to the right of the correct approach corridor, and that is why they clipped the trees. Nevertheless, the plane crashed killing thirty seven Marshall football players, the team’s coach, its doctors, the university athletic director and 25 team boosters members, who were some of Huntington, West Virginia’s most prominent citizens, and had traveled to North Carolina to cheer on the Thundering Herd. One of the citizens of the town of Huntington later wrote that “the whole fabric, the whole heart of the town was aboard.”

It had been a rough decade for the Thundering Herd. Their stadium had been condemned in 1962. It hadn’t been renovated since World War II. From the last game of the 1966 season, the team had not won a game. There had been some issues concerning recruiting violations as well, but the team seemed to be getting back on track. Dishonest coaches had been fired, the field had been rebuilt and they started winning games again. The loss to East Carolina was a real squeaker, and the team was looking forward to a better year the next season. Then disaster struck. For Huntington, the plane crash was “like the Kennedy assassination,” one citizen remembers. “Everybody knows where they were and what they were doing when they heard the news.” The town was in mourning. Shops closed, and windows were draped in black. The university held a memorial service and cancelled the Monday classes. The funerals seemed endless, taking place over the next few weeks. Everyone in town knew these people. Perhaps the saddest ceremony, was that of six players whose remains couldn’t be identified. They were buried together in Spring Hill Cemetery, on a hill overlooking their university.

Marshall got a new football coach…Jack Lengyel, from the College of Wooster in Ohio, who set about rebuilding the team. As a rule, Freshmen are not allowed to play on the Varsity squad, but Marshall was given special permission. Lengyel put together a mix of first year walk ons, and nine veteran players who had not been on the plane that night. It was a long road. The team lost the first game of the 1971 season, but in what seemed to be a miracle, they won their first home game against Ohio’s Xavier University 15-13, with a last second touchdown that seemed almost too good to be true. The team only won one other game that first season. During Lengyel’s four year tenure, they won nine other games, but none of those were as emotional as the first one. It was like they were playing for those who were lost, and maybe they were, or maybe it was because

they were playing at home. No matter what happened in the remaining years of Lengyel’s tenure, the town would never forget how he brought the sport out of the ashes and brought hope back to the town. It wasn’t that football was all they had, or even that it could remotely compare to the loss the town had experienced, but I think it was more about honoring those lost, by not giving up. Those lost were not quitters, nor were those who remained.

they were playing at home. No matter what happened in the remaining years of Lengyel’s tenure, the town would never forget how he brought the sport out of the ashes and brought hope back to the town. It wasn’t that football was all they had, or even that it could remotely compare to the loss the town had experienced, but I think it was more about honoring those lost, by not giving up. Those lost were not quitters, nor were those who remained.