soviet union

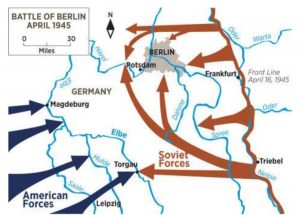

Sometimes, an event that potentially changed history, ends up getting little or no recognition. Thankfully, the picture that marked the event was taken, or the entire event might never have been noticed in history at all. This particular day is actually a very important day in the history of World War II, and therefore, the world. Elbe Day, which took place on April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau in Germany. This event marked an important step toward the end of World War II in Europe. If you have ever heard the saying, divide and conquer, you will know basically what happened on Elbe Day. A secret mission had been planned, and April 25, 1945, was the day it was carried out.

Sometimes, an event that potentially changed history, ends up getting little or no recognition. Thankfully, the picture that marked the event was taken, or the entire event might never have been noticed in history at all. This particular day is actually a very important day in the history of World War II, and therefore, the world. Elbe Day, which took place on April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau in Germany. This event marked an important step toward the end of World War II in Europe. If you have ever heard the saying, divide and conquer, you will know basically what happened on Elbe Day. A secret mission had been planned, and April 25, 1945, was the day it was carried out.

The plan was to have the Soviet army advance from the East, and the US Army advance from the West. The first contact between American and Soviet patrols occurred near Strehla exactly as planned, after First Lieutenant Albert Kotzebue, an American soldier, crossed the Elbe River in a boat with three men of an intelligence and reconnaissance platoon. Once they crossed to the east bank of the river, they met up with  forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of the First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gardiev. Later that day, another patrol under Second Lieutenant William Robertson with Frank Huff, James McDonnell and Paul Staub met a Soviet patrol commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Silvashko on the destroyed Elbe bridge of Torgau. When the two armies connected at the Elbe River, the cutting of Germany in half is accomplished. In doing so, the strength of the German army was severely weakened. The German army was split in two, just like the country was, and in the end, that split made it impossible for the Germans to really fight the war they were engaged in. It was the beginning of the end for them.

forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of the First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gardiev. Later that day, another patrol under Second Lieutenant William Robertson with Frank Huff, James McDonnell and Paul Staub met a Soviet patrol commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Silvashko on the destroyed Elbe bridge of Torgau. When the two armies connected at the Elbe River, the cutting of Germany in half is accomplished. In doing so, the strength of the German army was severely weakened. The German army was split in two, just like the country was, and in the end, that split made it impossible for the Germans to really fight the war they were engaged in. It was the beginning of the end for them.

Finally, on April 26, the commanders of the 69th Infantry Division of the First Army (United States) and the 58th Guards Rifle Division of the 5th Guards Army (Soviet Union) met at Torgau, southwest of Berlin. They knew that this moment was monumental, and it had to be documented. Arrangements were made for the  formal “Handshake of Torgau” photo to be taken of Robertson and Silvashko the following day, April 27. The Soviet, American, and British governments released simultaneous statements that evening in London, Moscow, and Washington, “reaffirming the determination of the three Allied powers to complete the destruction of the Third Reich.” They knew they must have victory at all costs.

formal “Handshake of Torgau” photo to be taken of Robertson and Silvashko the following day, April 27. The Soviet, American, and British governments released simultaneous statements that evening in London, Moscow, and Washington, “reaffirming the determination of the three Allied powers to complete the destruction of the Third Reich.” They knew they must have victory at all costs.

The fact that Elbe Day has never been an official holiday in any country, has not stopped people from looking to the day as something very special, and in the years after 1945 the memory of this friendly encounter gained new significance in the context of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Hijacking is usually associated with airplanes, but it is certainly not limited to airplanes, nor is it limited to any one country. One of the scariest situations for parents of school children is when their bus is hijacked. That is exactly what happened on December 1, 1988, when five armed criminals, led by Pavel Yakshiyants hijacked a LAZ-687 bus carrying around thirty pupils and one teacher from school 42 in Ordzhonikidze, Soviet Union (now Vladikavkaz in Russia).

Hijacking is usually associated with airplanes, but it is certainly not limited to airplanes, nor is it limited to any one country. One of the scariest situations for parents of school children is when their bus is hijacked. That is exactly what happened on December 1, 1988, when five armed criminals, led by Pavel Yakshiyants hijacked a LAZ-687 bus carrying around thirty pupils and one teacher from school 42 in Ordzhonikidze, Soviet Union (now Vladikavkaz in Russia).

Most countries don’t often concede to the demands of the hijackers, because it doesn’t guarantee the safety of the hostages, but in this case, the local authorities did concede to the hijackers’ demands and provided an Ilyushin Il-76 aircraft to fly the hijackers to Israel. It was a very strange situation, as hijackings go, because first of all, the hostages were released when the demands were met. Meeting the demands of the hijackers unequivocally, often results in the hostages being taken to another location, where the situation just continues to escalate. In this case, however the hijackers landed at Tel Aviv’s Ben Gurion Airport, and the hijackers surrendered to local troops and police without resistance. Then, Israel agreed to extradited to the men to the Soviet Union, where they were sentenced to prison terms. What made that very strange was that at that time Israel and the Soviet Union had no extradition treaty, because relations between the two countries were still severed. All hostages were released. The Defense Minister of Israel at the time, Yitzhak Rabin, criticized Soviet authorities for providing the hijackers with an aircraft and flying them to Israel in exchange for the release of the hostages, thereby making it Israel’s problem.

The hijacking was carried out by Pavel Levonovich Yakshiyants, Vladimir Alexandrovich Muravlev, German Lvovich Vishnyakov, Vladimir Robertovich Anastasov, and Tofiy Jafarov. Yakshiyants and Muravlev were prior convicts, while the others were first time offenders. Yakshiyants, an Armenian, was first convicted when he was 17 and sentenced to two years in prison for theft. That did little to deter him, and he was later sentenced to four years in prison for robbery. Then in 1972, he was sentenced to ten years, again for robbery, but somehow managed to be released on parle in 1979.

What had started out as a field trip, turned scary when a man approached them saying he was the driver sent to take them home. The group of 30–31 schoolchildren had just finished a field trip to a local printing plant when the hijacking occurred. Subsequently, the teacher and her pupils, aged 10 and 11, boarded the bus to find themselves the hostages of five armed people. The group was then used as a human shield and bargaining chip to make sure their demands were met. The hijackers rode to the local obkom, which is “literally the “Washington Province Party Committee” and is a derogatory term used in Russian media and speech to imply that many crucial decisions by political elites of Russia and some other post-Soviet states have been and are agreed with and/or taken in the United States.” The hijackers demanded about 2 million rubles, which is about US$3.3 million at the time, and an aircraft. The authorities agreed, but the airport of Ordzhonikidze was unable to handle the large Ilyushin Il-76 cargo aircraft that was sent. The hijackers were told that they would have free passage to airport of Mineralnye Vody, so they went there. The bus windows were curtained so that the law enforcement units could not see what was happening inside. Russia’s Alpha Group was mobilized for a possible hostage rescue. It was learned that the hijackers were planning to land in Tashkent to pick up a friend then fly to Pakistan, but changed their mind and chose Israel instead. According to Israeli Army commander Major General Amram Mitzna, the hijackers believed they would be safe in Israel because they had heard that recent Israeli elections had produced an anticommunist government. Boy, were they in for a surprise?

The Ilyushin Il-76 cargo aircraft was escorted by Israeli fighter aircraft and landed on a remote darkened runway. It was quickly surrounded by army and police vehicles and ambulances. According to an Ilyushin Il-76 crew member, the hijackers asked whether they had landed in Israel or Syria. They said that if it was Israel,  they would stay. Mitzna said that the hijackers demanded proof that they were actually in Israel. They wanted to hear Yiddish or see a Star of David. When a soldier on the runway spoke a few words in Yiddish, the hijackers left the aircraft with their hands in the air. The hostages were quickly secured and were flown back to Ordzhonikidze. Following the extradition, the ring leaders, Yakshiyants and Murlav were put on trial. In March 1989, Yakshiyants was sentenced by the Supreme Court of Russia to 15 years in prison. Murlav was sentenced to 14 years. The remaining defendants received sentences ranging from three to fourteen years. All of the hostages arrived home safely, none the worse off for their ordeal.

they would stay. Mitzna said that the hijackers demanded proof that they were actually in Israel. They wanted to hear Yiddish or see a Star of David. When a soldier on the runway spoke a few words in Yiddish, the hijackers left the aircraft with their hands in the air. The hostages were quickly secured and were flown back to Ordzhonikidze. Following the extradition, the ring leaders, Yakshiyants and Murlav were put on trial. In March 1989, Yakshiyants was sentenced by the Supreme Court of Russia to 15 years in prison. Murlav was sentenced to 14 years. The remaining defendants received sentences ranging from three to fourteen years. All of the hostages arrived home safely, none the worse off for their ordeal.

The Cold War, and the Soviet Union’s sudden announcement on August 30, 1961, to end a three-year moratorium on nuclear testing, brought about a shift in US policy, and a number of to nuclear test operations. One, known as Operation Fishbowl was a series of high-altitude nuclear tests in 1962 that were carried out by the United States as a part of the larger Operation Dominic nuclear test program. Flight-test vehicles were designed and manufactured by Avco Corporation. The test planned for the first half of 1962, called Bluegill, Starfish and Urraca were originally planned for the first half of 1962, but the first test attempt was delayed until June. Planning was complex, but necessary.

The Cold War, and the Soviet Union’s sudden announcement on August 30, 1961, to end a three-year moratorium on nuclear testing, brought about a shift in US policy, and a number of to nuclear test operations. One, known as Operation Fishbowl was a series of high-altitude nuclear tests in 1962 that were carried out by the United States as a part of the larger Operation Dominic nuclear test program. Flight-test vehicles were designed and manufactured by Avco Corporation. The test planned for the first half of 1962, called Bluegill, Starfish and Urraca were originally planned for the first half of 1962, but the first test attempt was delayed until June. Planning was complex, but necessary.

The launch sites were planned from Johnston Island in the Pacific Ocean north of the equator. The island was the chosen launch site, rather than the other locations in the Pacific Proving Grounds. However, the testing was not without push back. Even as early as 1958, Lewis Strauss, t hen chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, opposed doing any high-altitude tests at locations that had been used for earlier Pacific nuclear tests. The motivation for concern was the fear of the flash from the nighttime high-altitude detonations might blind civilians who were living on nearby islands. Still, Johnston Island was a remote location. It was more distant from populated areas than the other potential test locations. Nevertheless, in order to protect residents of the Hawaiian Islands from flash blindness or permanent retinal injury from the bright nuclear flash, the nuclear missiles of Operation Fishbowl were launched toward the southwest of Johnston Island. The detonation part of the test would be farther from Hawaii.

hen chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, opposed doing any high-altitude tests at locations that had been used for earlier Pacific nuclear tests. The motivation for concern was the fear of the flash from the nighttime high-altitude detonations might blind civilians who were living on nearby islands. Still, Johnston Island was a remote location. It was more distant from populated areas than the other potential test locations. Nevertheless, in order to protect residents of the Hawaiian Islands from flash blindness or permanent retinal injury from the bright nuclear flash, the nuclear missiles of Operation Fishbowl were launched toward the southwest of Johnston Island. The detonation part of the test would be farther from Hawaii.

The Urraca test involved about a 1 megaton yield at very high altitude of just over 621 miles. With the damage caused to satellites by the Starfish Prime detonation, the proposed Urraca test was always controversial. Because they couldn’t put the fears to rest, the Urraca test was finally canceled, and an extensive re-evaluation of the Operation Fishbowl plan as a whole was made during the 82-day operations pause after the Bluegill Prime disaster of July 25, 1962. When prime was added to a test, it indicated that the main test had failed, so when Bluegill Prime failed, it was the second test fail for that test series, which in this case (Bluegill Double Prime), ended in disaster when the Thor suffered a stuck valve preventing the flow of LOX to the combustion chamber. The engine lost thrust and unburned RP-1 spilled down into the hot thrust chamber, igniting and starting a fire around the base of the missile. Bluegill would go on to have two more tests, before they finally achieved success.

A test named Kingfish was added during the early stages of Operation Fishbowl planning. Two low-yield tests, Checkmate and Tightrope, were also added during the project, so the final number of tests in Operation Fishbowl was five. Tightrope was the last atmospheric nuclear test conducted by the United States, as the Limited Test Ban Treaty came into effect shortly thereafter. A total of Seven rockets carrying scientific instrumentation were launched from Johnston Island in support of the Tightrope test, which was the final atmospheric test conducted by the United States. I suppose testing is necessary, and I don’t know where else or how else it could be done, but the whole thing seems crazy to me. I do think that in light of this and other nuclear test disasters, care should be taken to better protect human life.

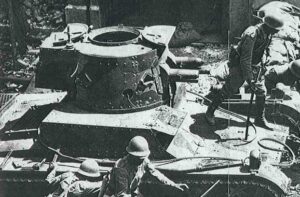

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

When the Germans surrendered at the end of World War II, Germany was divided into four areas of control by the Allied Powers…Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south, and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. That gave those four countries governing control over their own sections of Germany, and the people in those areas. Not every country was exactly planning to do what the people might consider to be their best interests. The Allied countries had the control and the ability to dish out punishment as they saw fit. The Soviet Union considered the forced labor of Germans as part of German war reparations for the damage inflicted by Nazi Germany on the Soviet Union during the Axis-Soviet campaigns (1941-1945) of World War II. They wanted to exact some measure of revenge, I guess, and they were in a position to make that happen.

So, the Soviet authorities deported German civilians from Germany and Eastern Europe to the USSR after World  War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

War II as forced laborers. It almost reminds me of what happened with the Holocaust, except that the Soviet Union had no interest in killing their captives. They wanted slave labor and a measure of retaliation. Ethnic Germans living in the USSR were conscripted for forced labor. German prisoners of war were also used as a source of forced labor during and after the war by the Soviet Union and by the Western Allies.

The decision was made and the fate of the German people was sealed. In 1946, the Soviet Union forcibly relocated more than 2,500 former Nazi German specialists, including scientists, engineers, and technicians who worked in specialist areas, from companies and institutions relevant to military and economic policy in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany (SBZ) and Berlin, along with around 4,000 family members, totaling more than 6,000 people, to the Soviet Union as war reparations. These specialists with all of their knowledge and abilities, could easily change the course of history in the Soviet Union, or any country they were placed in, for that matter. Still, not all of the forced labor were specialists. Many were unskilled labor, doing menial jobs.

The good thing was that the situation in Germany after World War II was appalling. Many of the people were homeless from the bombings. I suppose that, for that reason, the forced move, while scary, was not the worst thing in the world. It was possible that a new life in the Soviet Union could be favorable when compared to war-torn Germany. It is unclear whether any Germans who were sent to the Soviet Union chose to go back to Germany, because information about forced labor of Germans in the Soviet Union was suppressed in the Eastern Bloc until after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Many of those records could have also been destroyed.

What could make a nation go through an earthquake and refuse help from another nation, like the United States? It seems like a strange question, but it is valid. On October 6, 1948, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake leveled Ashgabat, the capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic—now Turkmenistan. The quake killed between 70,000 and 100,000 people. The true number will never be known. In fact, most information of the scope of the disaster remained unknown outside Central Asia until 1973, when archival records were finally unsealed by local officials. So…why seal the records…of an earthquake??

What could make a nation go through an earthquake and refuse help from another nation, like the United States? It seems like a strange question, but it is valid. On October 6, 1948, a magnitude 7.3 earthquake leveled Ashgabat, the capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic—now Turkmenistan. The quake killed between 70,000 and 100,000 people. The true number will never be known. In fact, most information of the scope of the disaster remained unknown outside Central Asia until 1973, when archival records were finally unsealed by local officials. So…why seal the records…of an earthquake??

The town of Ashgabat lies at the foot of the Kopet-Dag Mountain range near the border with Iran. The area is geologically unstable and earthquake prone. That said, why should a large earthquake in an earthquake-prone area need to be hidden? Ashgabat was originally a czarist outpost, founded in 1881. The town grew quickly during World War II, due to evacuees from the war zone. The population grew to an estimated 150,000 people. With a huge influx of people came the need for a lot of new housing, so single-story houses of unreinforced brick and stone, with heavy roofs of packed clay were quickly built, without regard for the need for earthquake proofing. I suppose that was the reason that the authorities didn’t want anyone to come in to help or to know the details of the catastrophe or the number of victims. The schools, hospitals, and other public buildings were built in the same shoddy way. It was wartime, so it may have been that supplies were scarce, or that proper time was not spent on the construction. Of course, less was known about how earthquakes affect buildings too, and even though there were existing seismic standards, they were seldom met. The builders greatly underestimated the earthquake danger, and that was a fact. A 1929 quake had already caused significant property damage, but strangely, the fault zone had been unusually inactive. I suppose this could have been a warning sign. When it is overdue, it may be a sign of an impending catastrophe.

In this case, that was exactly what happened. On October 6, 1948, at 1:17am, with few people awake. Suddenly, they an ominous rumbling from the mountains, followed immediately by violent vertical shaking. It was actually two strong shocks seconds apart, and just as suddenly, Ashgabat was reduced to rubble. There was no escape…there was no time for escape. The buildings were standing one second and collapsed the next. The thing that is the most shocking was that many of the survivors, who had been conditioned by propaganda in the acute early phase of the Cold War, thought that the city had been hit by an American atomic bomb. And the government did nothing to correct their misguided thinking. So, the country did not seek help from the United States.

As suddenly as it had occurred, the quake severed all communications with the outside world. There were no emergency centers, because hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies lay in ruins. The few remaining uninjured rescue workers, members of the city’s emergency services struggled in the darkness to help the injured. Doctors, many of whom had served in the war, pulled equipment from the ruins to set up an emergency station in Karl Marx Square. Finally, by the afternoon, reinforcements and supplies began to arrive from Tashkent and Baku. Nevertheless, the number of casualties, and the inherent difficulty of evacuating gravely wounded people, meant that help came too late for many. It was estimated that half of an estimated thirty thousand people who  had life-threatening injuries died from lack of early treatment…many people died before they could even be pulled from the rubble.

had life-threatening injuries died from lack of early treatment…many people died before they could even be pulled from the rubble.

While the city workers immediately ran to the damaged central headquarters of the Communist Party, where they were told by the party’s first secretary, S Batirova to take an undamaged automobile and head northward to a functioning telephone line, and soldiers stationed at the airport used an aircraft radio to contact Baku and Sverdlovsk, it was still many hours before any details reached areas from which aid could be dispatched.Unfortunately, that wasn’t much help either, because the railway station was in ruins, tracks were blocked, the airport control tower was destroyed, and the airport and roads could not handle heavy traffic. It would take hours and even days, to get the much-needed rescue support the city needed.

Of course, because of the misguided concept that the Americans were somehow involved, the precise death toll will never be known for sure. Estimates range from a shockingly low number of 400, suggested by Nature magazine in 1948, to a more likely number of 110,000. The dead were buried in mass graves. They were not counted or identified, adding to the confusion. There were roughly 50,000 survivors in a city that had previously had a population of approximately 150,000. That suggests that a death toll of 80,000 to 100,000, or about two-thirds of the population is a more accurate number.

The death toll was enormous, and that could have also accounted for the lack of emergency workers. It’s highly likely that many of them were among the dead or injured…not to mention the fact that there may have been a gross shortage of qualified rescue workers in the poorest part of a country, which was just still recovering from long years of war, but the poor response from the rest of the Soviet Union became more and more unconscionable. On October 7, Pravda printed a brief article stating only that “geologists at the Russian Academy of Sciences had detected a strong earthquake.” The article also reported that there were supply shipments and of the evacuation of the wounded, but no mention of the scope of devastation or the number of casualties. Of course, the international press used Pravda’s limited and incorrect reportage about the quake as the source for their own news reports.

To make matters worse, a conspiracy of silence followed the destruction of Ashgabat. Most history books and almanacs of natural disasters actually omit the quake entirely!! In the typical Soviet propaganda style of the 1950’s, they actually praised the severely lacking reconstruction efforts that completely ignored seismological standards. One Soviet journalist who visited the city in 1953, later described being “forbidden to photograph the omnipresent ruins or to report a march of weeping survivors to the mass graves on the outskirts of the city.” Little was known about the devastating earthquake until 1973. Only on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the event, did officials in Turkmenistan begin to open sealed archives and acknowledge the terrible calamity. Why was this? It was largely because of the Cold War, when both sides were eager not to expose their strategic vulnerabilities. That still doesn’t make sense, however, because the destruction of Ashgabat neither compromised the Soviet Union’s defense system nor revealed grave internal weaknesses. The forced silence did nothing to improve domestic morale in Russia, and it created widespread resentment in Central Asia.  Internationally the Soviet Union could have gained propaganda points by publicizing the disaster and then criticizing the lack of response from the West, but for some reason, they didn’t so that either. Of course, the people in the Soviet Union lived in fear of Joseph Stalins sweeping purges and force silence and timidity. They didn’t dare speak of any kind of vulnerability. Until Stalin’s death in 1953, even referencing the event was considered a dangerous move. Financial aid was still desperately needed decades after the disaster, yet it still didn’t really come. Silence translated into slow reconstruction. Substantial portions of the city remain in ruins, and a significant portion of the population still lives in temporary, or inadequate and unsafe, dwellings to this day.

Internationally the Soviet Union could have gained propaganda points by publicizing the disaster and then criticizing the lack of response from the West, but for some reason, they didn’t so that either. Of course, the people in the Soviet Union lived in fear of Joseph Stalins sweeping purges and force silence and timidity. They didn’t dare speak of any kind of vulnerability. Until Stalin’s death in 1953, even referencing the event was considered a dangerous move. Financial aid was still desperately needed decades after the disaster, yet it still didn’t really come. Silence translated into slow reconstruction. Substantial portions of the city remain in ruins, and a significant portion of the population still lives in temporary, or inadequate and unsafe, dwellings to this day.

Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin had just finished speaking at a factory in Moscow, when Fanya Kaplan, a member of the Social Revolutionary party shot him twice. Lenin, the leader of the Bolsheviks was seriously wounded, but survived the attack. The attempted assassination basically set off a “gang war” of sorts, although to a much larger degree…a Civil War, really. That war, known as Red Terror, set off a wave of reprisals by the Bolsheviks against the Social Revolutionaries and other political opponents. As Russia fell deeper into civil war, thousands of people were executed. This had been coming since 1887, but would not fully materialize until the assassination of Petrograd Cheka leader Moisei Uritsky and the attempted assassination of Vladimir Lenin.

Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin had just finished speaking at a factory in Moscow, when Fanya Kaplan, a member of the Social Revolutionary party shot him twice. Lenin, the leader of the Bolsheviks was seriously wounded, but survived the attack. The attempted assassination basically set off a “gang war” of sorts, although to a much larger degree…a Civil War, really. That war, known as Red Terror, set off a wave of reprisals by the Bolsheviks against the Social Revolutionaries and other political opponents. As Russia fell deeper into civil war, thousands of people were executed. This had been coming since 1887, but would not fully materialize until the assassination of Petrograd Cheka leader Moisei Uritsky and the attempted assassination of Vladimir Lenin.

Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov was born on April 22, 1870, in Simbirsk, Russian Empire. After his brother was executed in 1887 for plotting to assassinate Czar Alexander III, Ulyanov became interested in the revolutionary cause, also adopting the pseudonym…Lenin. He decided to study law and upon completion, took up practice in Petrograd, which is now Saint Petersburg. In Petrograd, Lenin began to associate with people from the revolutionary Marxist circles. Soon, he was organizing a Marxist group in the capital to enlist workers to the Marxist cause. He called the new group, “Union for the Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class.” Following the December 1895, arrest of Lenin and the other leaders of the Union, Lenin was jailed for a year. Upon his release, he was exiled to Siberia for a term of three years.

After his term in jail, and the subsequent exile, Lenin went to Western Europe in 1900, where he continued his revolutionary activity. In 1902, while in Western Europe that he published a pamphlet titled “What Is to Be Done?,” which argued that only a disciplined party of professional revolutionaries could bring socialism to Russia. Of course, most of us know that Lenin was working in the shadows to get back into the Russian Marxist system. In 1903, he met with other Russian Marxists in London and established the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party (RSDWP), but while he tried really hard, there was discord from the start. There remained a split between Lenin’s Bolsheviks (Majoritarians), who advocated militarism, and the Mensheviks (Minoritarians), who advocated a democratic movement toward socialism. There is a saying, about a house divided…it just can’t stand. These two groups increasingly opposed each other within the framework of the RSDWP, and Lenin made the split official at a 1912 conference of the Bolshevik Party.

After the outbreak of the Russian Revolution of 1905, Lenin made his move, and returned to Russia. The revolution, which consisted mainly of strikes throughout the Russian empire, came to an end when Nicholas II promised reforms, including the adoption of a Russian constitution and the establishment of an elected legislature. Then, when order had been restored, as often happens in government, the czar nullified most of these reforms. That forced Lenin to go into exile again in 1907.

Lenin was opposed to World War I, which began in 1914, calling it “an imperialistic conflict” and called on “working-class” soldiers to turn their guns on the capitalist leaders who “sent them down into the murderous trenches.” Lenin was pushing for a socialist agenda by appealing to the middle-income people who felt like they should be given a handout by the government to supplement their income. Little did they know that socialism is never the best solution. War is always hard on the countries involved, but World War I was an unprecedented disaster for Russia. The Russian casualties were greater than those sustained by any other nation in any previous war. The war also left the economy hopelessly disrupted by the costly war effort. By March of 1917, things had gotten so bad that riots and strikes broke out in Petrograd over the scarcity of food. To make matters worse, army troops who had lost confidence in the leadership joined the strikers, and on March 15 Nicholas II was forced to abdicate, which brought to an end centuries of czarist rule. Following the February Revolution, so named because of Russia’s use of the Julian calendar, power was shared between the ineffectual Provincial Government and the soviets, or “councils” of soldiers’ and workers’ committees.

German authorities allowed Lenin and his lieutenants to secretly cross Germany en route from Switzerland to Sweden in a sealed railway car, after the outbreak of the February Revolution. The hope was that the return of the anti-war Socialists to Russia would undermine the Russian war effort, which had been continued under the Provincial Government. Lenin began to push for the overthrow of the Provincial Government by the soviets, an act for which he was condemned as a “German agent” by the government’s leaders. Forced to escape to Finland in July, his call for “peace, land, and bread” met with increasing popular support, and the Bolsheviks won a majority in the Petrograd soviet. Then, in October, Lenin secretly returned to Petrograd, and on November 7th the Bolshevik-led Red Guards took down the Provisional Government and proclaimed soviet rule.

Following the coup, Lenin became the virtual dictator of the world’s first Marxist state. His government made peace with Germany, nationalized industry, and distributed land but beginning in 1918, it all began to fall apart. The nation sank into a devastating civil war against czarist forces. In 1920, the czarists were defeated, and in

1922 the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was established. Upon Lenin’s death in early 1924, his body was embalmed and placed in a mausoleum near the Moscow Kremlin. Petrograd was renamed Leningrad in his honor. After a struggle of succession, fellow revolutionary Joseph Stalin succeeded Lenin as leader of the Soviet Union. The Lenin years were finally over.

1922 the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was established. Upon Lenin’s death in early 1924, his body was embalmed and placed in a mausoleum near the Moscow Kremlin. Petrograd was renamed Leningrad in his honor. After a struggle of succession, fellow revolutionary Joseph Stalin succeeded Lenin as leader of the Soviet Union. The Lenin years were finally over.

Hitler never had feeling of any kind toward mankind of any nationality, race, gender, or religion, even though there were those he hated more than others…specifically, Jews, Gypsies, Blacks, and anyone not blond haired and blue eyed. Nevertheless, Hitler had long ago decided that anyone was disposable, except him. He didn’t tell other people about that, of course. On July 8, 1941, the German army invaded Pskov, a city located 180 miles from Leningrad, Russia. General Franz Halder, the chief of the German army general staff recorded Hitler’s plans for Moscow and Leningrad in his diary, and it wasn’t good. Hitler planned “To dispose fully of their population, which otherwise we shall have to feed during the winter.” Basically, he considered them all to be “useless eaters” and planned to kill them. Then, he planned to turn Moscow into a lake.

Hitler never had feeling of any kind toward mankind of any nationality, race, gender, or religion, even though there were those he hated more than others…specifically, Jews, Gypsies, Blacks, and anyone not blond haired and blue eyed. Nevertheless, Hitler had long ago decided that anyone was disposable, except him. He didn’t tell other people about that, of course. On July 8, 1941, the German army invaded Pskov, a city located 180 miles from Leningrad, Russia. General Franz Halder, the chief of the German army general staff recorded Hitler’s plans for Moscow and Leningrad in his diary, and it wasn’t good. Hitler planned “To dispose fully of their population, which otherwise we shall have to feed during the winter.” Basically, he considered them all to be “useless eaters” and planned to kill them. Then, he planned to turn Moscow into a lake.

The Germans first launched a massive invasion of the Soviet Union, called Operation Barbarossa, on June 22, using over 3 million men. Since the Soviet army was unsuspecting and unprepared, the Germans were very successful in their attack. By July 8th, the Germans had captured more than 280,000 Soviet soldiers and almost 2,600 tanks had been destroyed. With the Germans already a couple of hundred miles inside Soviet territory, Stalin was in a state of panic. He began executing any of his generals who had failed to stop the advancing attack. That was likely a big mistake, because he was basically defeating himself from the inside.

As chief of staff, Halder had been keeping a diary of Hitler’s day-to-day decision-making process. His documentation of Hitler’s processes showed the flaws that Hitler had. I don’t know if that was his plan or if he had wanted to emulate Hitler, but as became emboldened by his successes in Russia, Halder recorded that the “Fuhrer is firmly determined to level Moscow and Leningrad to the ground.” It was Halder’s opinion that Hitler  had underestimated the Russian army’s numbers and the bitter infighting between factions within the military about strategy. Halder and several others thought they should head straight to Moscow, as taking the capital would bring down the entire country. Nevertheless, Hitler was the leader, and as such, he wanted to meet up with Field Marshal Wilhelm Leeb’s army group, which was making its way toward Leningrad. The biggest mistake Hitler made was the fact that Winter was coming, and the Russians were much more used to the Soviet Winter’s frigid temperatures than the Germans…an advantage that would eventually catch up to the Germans. The advantage of such conditions would give the Russians the victory over the Germans in this battle.

had underestimated the Russian army’s numbers and the bitter infighting between factions within the military about strategy. Halder and several others thought they should head straight to Moscow, as taking the capital would bring down the entire country. Nevertheless, Hitler was the leader, and as such, he wanted to meet up with Field Marshal Wilhelm Leeb’s army group, which was making its way toward Leningrad. The biggest mistake Hitler made was the fact that Winter was coming, and the Russians were much more used to the Soviet Winter’s frigid temperatures than the Germans…an advantage that would eventually catch up to the Germans. The advantage of such conditions would give the Russians the victory over the Germans in this battle.

The first official space flight occurred on April 12, 1961, when Soviet astronaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful crewed spaceflight, became the first human to journey into outer space. Traveling on Vostok 1, Gagarin completed one orbit of Earth on 12 April 1961. While that was the first official manned space flight, there were other times that man touched space.

The first official space flight occurred on April 12, 1961, when Soviet astronaut Yuri Alekseyevich Gagarin, a Soviet pilot and cosmonaut who, aboard the first successful crewed spaceflight, became the first human to journey into outer space. Traveling on Vostok 1, Gagarin completed one orbit of Earth on 12 April 1961. While that was the first official manned space flight, there were other times that man touched space.

The North American X-15 was an experimental US single seat rocket powered airplane that was taken aloft by a B-52 bomber acting as its “mother ship” and released to test extremely high speed and extremely high-altitude flight. The first such flight took place on June 8, 1959.

The hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft known as the North American X-15, was operated by the United States Air Force and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration as part of the X-plane series of experimental aircraft. While it didn’t exactly go into space, the X-15 set speed and altitude records in the 1960s, reaching the edge of outer space and returning with valuable data used in aircraft and spacecraft design, making it a precursor to the spacecraft of today. The X-15’s highest speed, 4,520 miles per hour , was achieved on October 3, 1967, when William J Knight flew at Mach 6.7 at an altitude of 102,100 feet or 19.34 miles. This set the official world record for the highest speed ever recorded by a crewed, powered aircraft, and it remains unbroken to this day.

While pilot, William Knight flew an all-time record speed of Mach 6.7 (4520 miles per hour), the fastest speed flown by a powered and manned piloted aircraft, in 1967, his flight wasn’t the first record setting flight in the X-15. This incredible speed was not even close to the maximum potential of the X-15. A typical commercial passenger jet flies at a speed of about 460 – 575 miles per hour, when cruising at about 36,000 feet, which figures to about 75-85% of the speed of sound. I can’t imagine going any faster than that, much less wrap my head around more than 4520 miles per hour!!

In 1963, pilot Joe Walker flew his X-15 into the history books by flying it to a record altitude of 67 miles and achieving a speed of almost Mach 5 (3794 miles per hour). While there is no sharp physical boundary that marks the end of atmosphere and the beginning of space, it is generally marked at the Karman line, and for purposes of space flight defined as an altitude of 60 miles, although some place the line at 50 miles above Earth’s mean sea level.

The X-15 program continued until 1968, when the rocket planes were retired. On notable pilot was Neil Armstrong, who was also the first man to walk on the Moon, of course. Armstrong made 7 flights in the speedy rocket plane. Also interesting to note is the fact that during the X-15 program, 12 pilots flew a combined 199 flights. Of the 12 pilots, 8

pilots flew a combined 13 flights that exceeded the altitude of 50 miles, thus qualifying these pilots as being astronauts!! Of those 13 flights, two (flown by the same civilian pilot) met the FAI (Féderátion Aéronautique Internationale) definition of 62 miles of outer space. The 5 Air Force pilots qualified for military astronaut wings immediately, while the 3 civilian pilots were eventually awarded NASA astronaut wings in 2005, 35 years after the last X-15 flight.

pilots flew a combined 13 flights that exceeded the altitude of 50 miles, thus qualifying these pilots as being astronauts!! Of those 13 flights, two (flown by the same civilian pilot) met the FAI (Féderátion Aéronautique Internationale) definition of 62 miles of outer space. The 5 Air Force pilots qualified for military astronaut wings immediately, while the 3 civilian pilots were eventually awarded NASA astronaut wings in 2005, 35 years after the last X-15 flight.

What would make a tiny nation try to invade a nation that is more that 25 times larger, with a population that is at least 8 times larger? It makes no sense, and yet on February 15, 1937, Japan attempted to invade China. Japan, with a total of 60,000 soldiers enter Northern China using planes and tanks. The invasion was something they had studied so they would have a plan before they attempted such an outlandish scheme. The type of conquest they were trying to mimic was that of Kubia Kahn, the Mongol emperor, who in 1271, established the Yuan dynasty and formally claimed orthodox succession from prior Chinese dynasties. The Yuan dynasty came to rule over most of present-day China, Mongolia, Korea, southern Siberia, and other adjacent areas. Kahn also amassed influence in the Middle East and Europe as khagan. By 1279, the Yuan conquest of the Song dynasty was completed, and Kahn became the first non-Han emperor to rule all of China proper.

What would make a tiny nation try to invade a nation that is more that 25 times larger, with a population that is at least 8 times larger? It makes no sense, and yet on February 15, 1937, Japan attempted to invade China. Japan, with a total of 60,000 soldiers enter Northern China using planes and tanks. The invasion was something they had studied so they would have a plan before they attempted such an outlandish scheme. The type of conquest they were trying to mimic was that of Kubia Kahn, the Mongol emperor, who in 1271, established the Yuan dynasty and formally claimed orthodox succession from prior Chinese dynasties. The Yuan dynasty came to rule over most of present-day China, Mongolia, Korea, southern Siberia, and other adjacent areas. Kahn also amassed influence in the Middle East and Europe as khagan. By 1279, the Yuan conquest of the Song dynasty was completed, and Kahn became the first non-Han emperor to rule all of China proper.

So, with dreams of power and world domination, among other things, including a need for the resources Japan lacked and China had, the Japanese army under Emperor Hirohito made the decision to attack the much larger  and more populated China. They threatened to bottle up 400,000 Chinese people on China’s central front. The attack area was approximately 20 miles, from the Yellow River to the Henan Capital provincial (Kaifeng). The Japanese Army displayed far superior air power and many more combat troops during the Japanese onslaught. In fact, their might could easily be called terrifying. China was helpless at stopping the Japanese forces from occupying Shanghai, and they were barely able prevent the invasion of Japan on the capital. The Chinese desperately tried to fight back with small caliber weapons against the heavy artillery fire power, air and naval might, and armored defenses of Japan. While they were severely outgunned, the bravery, stubbornness and determination of the Chinese made it possible for the country to withstand three months of defending Shanghai. Nevertheless, in the end, Shanghai fell, and Japan gained control over the city. The best of China’s troops were defeated. Still, the Japanese were surprised at the length of time that the Chinese troops were able to make a stand for their capital city. Because of their military superiority, the Japanese fully expected a short battle and a swift victory. They were not prepared for the one variable…the determination of the Chinese

and more populated China. They threatened to bottle up 400,000 Chinese people on China’s central front. The attack area was approximately 20 miles, from the Yellow River to the Henan Capital provincial (Kaifeng). The Japanese Army displayed far superior air power and many more combat troops during the Japanese onslaught. In fact, their might could easily be called terrifying. China was helpless at stopping the Japanese forces from occupying Shanghai, and they were barely able prevent the invasion of Japan on the capital. The Chinese desperately tried to fight back with small caliber weapons against the heavy artillery fire power, air and naval might, and armored defenses of Japan. While they were severely outgunned, the bravery, stubbornness and determination of the Chinese made it possible for the country to withstand three months of defending Shanghai. Nevertheless, in the end, Shanghai fell, and Japan gained control over the city. The best of China’s troops were defeated. Still, the Japanese were surprised at the length of time that the Chinese troops were able to make a stand for their capital city. Because of their military superiority, the Japanese fully expected a short battle and a swift victory. They were not prepared for the one variable…the determination of the Chinese  people. Morale plummeted over the heavy losses incurred, but not for long.

people. Morale plummeted over the heavy losses incurred, but not for long.

I sometimes wonder if these heads of governments really think that they can somehow control the world, or even, if they really think they can control the country they have invaded. The main reasons that nations and borders change as often as they do, is that people will only live under oppression for so long. Then, they will fight back. As to the heads of nations and ruling the world. While they might be the “head” of their nation, in a situation of world domination, I seriously doubt if any of these national leaders would be the one in control.

To most of us, committing espionage against our own country is…unthinkable, but there are those among us who wouldn’t give that a second thought. I think most countries have spies who do their best to find out information about another country, and I suppose that by design, that would mean that someone would have to commit espionage. I guess the two would go hand in hand, and it would depend on just how loyal a person was as to the limits they would go.

To most of us, committing espionage against our own country is…unthinkable, but there are those among us who wouldn’t give that a second thought. I think most countries have spies who do their best to find out information about another country, and I suppose that by design, that would mean that someone would have to commit espionage. I guess the two would go hand in hand, and it would depend on just how loyal a person was as to the limits they would go.

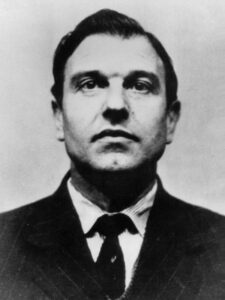

George Blake, who was born George Behar on November 11, 1922, was a British MI6 agent, and at one time thought to be a loyal agent, but during his time as a prisoner of war in Seoul, during the Korean War, he was apparently converted into a Communist, and strategically set up to be a double-agent. I suppose there is a number of prisoners of war who traded secrets for life and freedom from torture, and some who honestly changed their viewpoint, but to me it is outrageous. George Blake must  not have seen it that way, because he was a double-agent until he got caught in 1961.

not have seen it that way, because he was a double-agent until he got caught in 1961.

During his active double-agent years, he is believed to have betrayed the names of more than 40 British agents to the Soviets. Many of those he betrayed disappeared and were thought to have been executed. His betrayals basically destroyed British secret service operations in the Middle East. It must have been almost impossible to get agents to work in that region. Blake is believed to have passed on the names of almost every British agent working in Cairo, Damascus, and Beirut. Lord Parker, Lord  Chief Justice, the judge sentencing him, likened his actions to treason, and said, “It is one of the worst that can be envisaged other than in a time of war.” Blake was charged under the Official Secrets Act in May 1961. Blake pleaded guilty to five counts of passing secrets to the Soviet authorities during his trial, part of which was held in camera.

Chief Justice, the judge sentencing him, likened his actions to treason, and said, “It is one of the worst that can be envisaged other than in a time of war.” Blake was charged under the Official Secrets Act in May 1961. Blake pleaded guilty to five counts of passing secrets to the Soviet authorities during his trial, part of which was held in camera.

In 1966, Blake escaped from Wormwood Scrubs prison after serving five years of his sentence and having been removed from the list of likely escapers after only a year. Apparently, his supposed acceptance of his exceptionally long sentence lulled wardens into a false sense of security. It is assumed that he had help from the Soviet Union, and after his escape, he was quickly whisked away to the Soviet Union, where he lived out his life. He passed away in Moscow, Russia on December 26, 2020, at the age of 98 years.