fire

The USS Miami (SSN-755) was a Los Angeles-class submarine of the United States Navy. Ships and submarines are commonly named after cities and people, and the USS Miami submarine was the third vessel of the US Navy to be named after Miami, Florida. The USS Miami was also the forty-fourth Los Angeles-class (688) submarine and the fifth Improved Los Angeles-class (688I) submarine to be built and commissioned. The Electric Boat division of General Dynamics Corporation in Groton, Connecticut, won the contract on November 28, 1983. The keel was laid down on October 24, 1986, and USS Miami launched on November 12, 1988. She was commissioned on June 30, 1990 with Commander Thomas W Mader in command.

The USS Miami (SSN-755) was a Los Angeles-class submarine of the United States Navy. Ships and submarines are commonly named after cities and people, and the USS Miami submarine was the third vessel of the US Navy to be named after Miami, Florida. The USS Miami was also the forty-fourth Los Angeles-class (688) submarine and the fifth Improved Los Angeles-class (688I) submarine to be built and commissioned. The Electric Boat division of General Dynamics Corporation in Groton, Connecticut, won the contract on November 28, 1983. The keel was laid down on October 24, 1986, and USS Miami launched on November 12, 1988. She was commissioned on June 30, 1990 with Commander Thomas W Mader in command.

All that is fairly normal and mundane, but USS Miami was to have some much more “exciting” for lack of a better word, times in her future. USS Miami became the first submarine to conduct combat operations in two theaters since World War II, participating in Operation Desert Fox and Operation Allied Force. The submarine also became a movie star when she was featured in The Learning Channel (TLC) Extreme Machine episode on “Nuclear Submarines” but that was not even the craziest event in her history.

On May 23, 2012, at 5:41pm EDT, fire crews were called out with a report of a fire on the USS Miami. At the  time, she was being overhauled at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine. That would seem like a fairly safe place to be, but I suppose that anytime work is being done, accidents could happen. On that day, USS Miami was in the second month of a scheduled 20-month maintenance cycle. That meant that the “Engineering Overhaul” she was undergoing was extensive. The fire was a major one that injured seven firefighters. In addition, one crew member suffered broken ribs when he fell through a hole left by removed deck plates during the fire. The fire took 12 hours to extinguish.

time, she was being overhauled at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine. That would seem like a fairly safe place to be, but I suppose that anytime work is being done, accidents could happen. On that day, USS Miami was in the second month of a scheduled 20-month maintenance cycle. That meant that the “Engineering Overhaul” she was undergoing was extensive. The fire was a major one that injured seven firefighters. In addition, one crew member suffered broken ribs when he fell through a hole left by removed deck plates during the fire. The fire took 12 hours to extinguish.

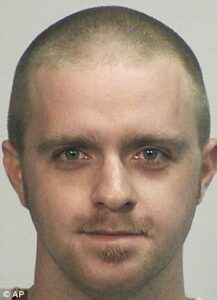

At first, the US Navy said that the blaze was caused by an industrial vacuum cleaner that was used “to clean worksites on the sub after shipyard workers’ shifts” that had sucked up a heat source that ignited debris inside the vacuum. However, on July 23, 2012, civilian painter and sandblaster Casey J Fury was indicted on two counts of arson after confessing to starting the fire. The reason for Fury’s actions really makes no sense to me. Fury said he lit rags on a berthing compartment’s top bunk so he could get out of work early…seriously!! That is insane, but then I guess any reason for arson has a degree of insanity attached to it. Still, this is the most bizarre reason I can think of. For Pete’s sake, tell your boss you need to be off early, or just quit. The consequences of this action were about to be heavy. On March 15, 2013, Fury was sentenced to more than 17 years in federal prison and ordered to pay $400 million in restitution. Casey Fury is still serving his 17-year prison sentence. He is scheduled to be released on August 4, 2027

For more than a year, the USS Miami’s fate was up in the air. Within a month of the fire, Maine Senators Susan  Collins and Olympia Snowe advocated for repairing the submarine. Navy leaders asked Congress to add $220 million to the operations and maintenance budget for emergent and unfunded ship repairs in July 2012. In August, the Navy decided to repair the boat for an estimated total cost of $450 million. They planned to reduce the repair cost by using spare parts from the recently decommissioned USS Memphis and by repairing rather than replacing damaged hull sections, as had been done with another Los Angeles-class boat, USS San Francisco. Unfortunately, these plans wouldn’t work for the USS Miami which was newer and so the parts and such were not available. In the end, the repairs would have cost an estimated $700 million.

Collins and Olympia Snowe advocated for repairing the submarine. Navy leaders asked Congress to add $220 million to the operations and maintenance budget for emergent and unfunded ship repairs in July 2012. In August, the Navy decided to repair the boat for an estimated total cost of $450 million. They planned to reduce the repair cost by using spare parts from the recently decommissioned USS Memphis and by repairing rather than replacing damaged hull sections, as had been done with another Los Angeles-class boat, USS San Francisco. Unfortunately, these plans wouldn’t work for the USS Miami which was newer and so the parts and such were not available. In the end, the repairs would have cost an estimated $700 million.

Finally, on August 6, 2013, the US Navy announced its intention to decommission USS Miami, because the cost was more than it could afford in a time of budget cuts. For the USS Miami it was a sad defeat. The sub was officially decommissioned on March 28, 2014, to be scrapped by the Ship-Submarine Recycling Program.

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

Every time there is a great event like the Olympics, the World’s Fair, or in this case, the Great Exhibition, a stunning new building or structure is built to house the event. The Crystal Palace was originally located in Hyde Park, London, England. It was a cast iron and plate glass structure, built to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Great Exhibition took place from May 1 to October 15, 1851, with more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet exhibition hall to display their own examples of the latest technology they had developed in the Industrial Revolution. The Crystal Palace was designed by Joseph Paxton. It was 1,851 feet long, with an interior height of 128 feet. It was three times the size of Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Some say that the name of the building came from a piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Exhibition, referring to a “palace of very crystal.”

The design called for 60,000 panes of glass to adorn the building. On average, a team of 80 men could fix more than 18,000 panes of sheet glass in a week. These were manufactured by the Chance Brothers. The building was finished in 39 weeks. The Crystal Palace boasted the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building. Visitors were shocked and astonished by all the clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights. The interior of the building had full grown trees!! The full-size elm trees that had been growing in the park were simply enclosed within the central exhibition hall near the 27-foot-tall Crystal Fountain. While very nice looking, the trees caused a problem with sparrows becoming a nuisance, and of course, shooting was out of the question inside a glass building. When Queen Victoria mentioned this problem to the Duke of Wellington, he offered the solution, “Sparrowhawks, Ma’am.” Now to me, that is incredulous, because you would simply be replacing on kind of bird with another, and then there was the added problem of bird violence. I don’t think the visitors would be very thrilled about the fighting birds or dropping bodies.

Incredibly, the Palace was relocated after the Great Exhibition, to an open area of South London known as Penge Place which had been excised from Penge Common. The building was rebuilt at the top of Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, which is an affluent suburb. The Crystal Palace stood in that location from June 1854 until a fire destroyed it in November 1936. After the fire, the suburb was renamed Crystal Palace after the landmark. In addition, a park was placed in the area and named Crystal Palace Park. It surrounds the site, and is home of the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre, which was previously a football stadium that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914. Crystal Palace Football Club were founded at the site and played at the Cup Final venue in their early years. The site still contains Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins’s Crystal Palace Dinosaurs which date back to 1854.

In the 1920s, a board of trustees was set up under the guidance of manager Sir Henry Buckland. Buckland was a fair man with a great love for the Crystal Palace, decided to restore the building. Following the restoration, the visitors returned, and the Crystal Palace started to become profitable again. Buckland and his staff also worked on improving the fountains and gardens, including the Thursday evening displays of fireworks by Brocks. Then, on the evening of November 30, 1936, Buckland was walking his dog near the Palace with his daughter Crystal. Buckland had named her after the building. Always looking at the building he loved, they noticed a red glow coming from inside. Buckland went in to investigate and found two of his employees fighting a small office fire that had started after an explosion in the women’s cloakroom. Buckland could see that this was a serious fire, so they called the Penge fire brigade. It was too late. Even with the 89 fire engines and over 400 firemen, the fire was too big and too out of control to be able to extinguish it.

The infamous Crystal Palace was destroyed. The fire was so big that its glow could be seen across eight counties. With high winds that night, the fire spread quickly, and in part because of the dry old timber flooring, and the huge quantity of flammable materials in the building it burned to the ground. Buckland said, “In a few hours we have seen the end of the Crystal Palace. Yet, it will live in the memories not only of Englishmen, but the whole world.” The fire brought one-hundred thousand spectators to Sydenham Hill that night. One of the

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

spectators was Winston Churchill, who said, “This is the end of an age.” Unfortunately, as was common for the era, the Crystal Palace was underinsured, and with a potential rebuild cost of at least £2 million, the building was never rebuilt. John Logie Baird, who had used the South Tower and much of the lower level of the building for mechanical television experiments. Much of his work was destroyed in the fire, and Baird suspected the fire was an act of arson to destroy his work on developing television. Nevertheless, the true cause remains unknown.

New safety laws usually come about as a direct result of a disaster or some other traumatic event. Such was the case with the laws formed after the fire and subsequent sinking of SS Yarmouth Castle. The ship was originally built as Evangeline, and it was an American steamship. It was the second of two identical ships built by the William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Company for the Eastern Steamship Lines for service on the New York City to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia route, operating in practice out of Boston as well. As with many ships, Evangeline was pulled into service during World War II and turned over to the War Shipping Administration, which operated all oceangoing vessels for the United States. During its war years, it was used primarily as an army troop transport. On July 1, 1946, after the war was over, Eastern Steamship Lines resumed control of the ship. Following its war service, it was put back in normal service for a short period and then, the ship was laid up. In 1954, it was sold and put under Liberian registry, operating from Boston to Nova Scotia, then to the Caribbean. In 1963 Evangeline was sold again, put under Panamanian registry. Then, it was renamed SS Yarmouth Castle. It was operated by Yarmouth Cruise Lines between Miami and Nassau, Bahamas, from 1964 until the disaster on November 13, 1965.

New safety laws usually come about as a direct result of a disaster or some other traumatic event. Such was the case with the laws formed after the fire and subsequent sinking of SS Yarmouth Castle. The ship was originally built as Evangeline, and it was an American steamship. It was the second of two identical ships built by the William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Company for the Eastern Steamship Lines for service on the New York City to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia route, operating in practice out of Boston as well. As with many ships, Evangeline was pulled into service during World War II and turned over to the War Shipping Administration, which operated all oceangoing vessels for the United States. During its war years, it was used primarily as an army troop transport. On July 1, 1946, after the war was over, Eastern Steamship Lines resumed control of the ship. Following its war service, it was put back in normal service for a short period and then, the ship was laid up. In 1954, it was sold and put under Liberian registry, operating from Boston to Nova Scotia, then to the Caribbean. In 1963 Evangeline was sold again, put under Panamanian registry. Then, it was renamed SS Yarmouth Castle. It was operated by Yarmouth Cruise Lines between Miami and Nassau, Bahamas, from 1964 until the disaster on November 13, 1965.

On November 12, 1965, Yarmouth Castle departed Miami for Nassau carrying 376 passengers and 176 crew members for a total of 552 people. The ship was due to arrive in Nassau the next day. The captain on the voyage was 35-year-old Byron Voutsinas. Shortly after midnight on November 13, a fire broke out in room 610 on the main deck. Being used as a storage space, the room was filled with mattresses, chairs, and other combustible materials. Unfortunately, the room did not have a sprinkler system, and in the end, the source of the fire could not be determined. It is thought that jury-rigged wiring might have thrown sparks that then entered the room through the ventilation ducts, but simple carelessness was not ruled out either.

A normal patrol went by the room between 12:30am and 12:50am, but they failed to systematically check all areas of the ship and detect the fire. At some point between midnight and 1:00am, the crew and passengers began noticing smoke and heat. Finally, a search was started to find the fire. By the time they discovered it in room 610 and the toilet above that room, it had already begun to spread and attempts to fight the fire with fire extinguishers were useless. Attempts to activate a fire alarm box were also unsuccessful. The bridge was unaware of the fire until about 1:10am, and by that time, Yarmouth Castle was 120 miles east of Miami and 60 miles northwest of Nassau, and in deep trouble. Since the radio room became involved, they were unable to call for help, or even call for the passengers to abandon ship.

The captain proceeded to the lifeboat containing the emergency radio, but he could not reach it. He and several crew members launched another lifeboat and abandoned ship at about 1:45am. The captain later testified that he wanted to reach one of the rescue vessels to make an emergency call. The remaining crew proceeded to alert passengers and attempted to help them escape their cabins. Some passengers tried to escape through cabin windows but couldn’t open them due to improper maintenance. The sprinkler system finally activated but was pretty much ineffective due to the severity of the fire. Crew members attempted to battle the flames with hoses, but they were hampered by low hydrant pressure. The investigation later determined that more valves were open than the pumps could handle.

Some of the lifeboats burned and others could not be launched due to mechanical problems. Only about half of the ship’s boats made it safely away. Passengers near the bow could not reach the lifeboats, but some were later picked up by boats from rescue vessels. The Finnish freighter Finnpulp was just eight miles ahead of Yarmouth Castle, also headed east. That ship’ crew noticed at 1:30am, that Yarmouth Castle had slowed significantly on the radar screen. Looking back, they saw the flames and notified their captain, John Lehto, who had been asleep. Lehto immediately ordered Finnpulp turned around. The Finnpulp successfully contacted the Coast Guard in Miami. It was the first distress call sent out. The passenger liner Bahama Star was following Yarmouth Castle at about twelve miles distance. At 2:15am, Captain Carl Brown noticed rising smoke and a red glow on the water. Realizing that this was Yarmouth Castle, he ordered the ship ahead at full speed. Bahama Star radioed the US Coast Guard at 2:20am.

Though rescue efforts were largely successful, for those who survived, 90 people lost their lives. Yarmouth  Castle capsized onto her port side just before 6:00am and sank at 6:03am. The wreck has not been located but is thought to rest 10,800 feet below the Atlantic. “The Yarmouth Castle disaster prompted updates to the Safety of Life at Sea law, or SOLAS. The updated law brought new maritime safety rules, requiring fire drills, safety inspections, and structural changes to new ships. Under SOLAS, any vessel carrying more than 50 overnight passengers is required to be built entirely of non-combustible materials such as steel. Yarmouth Castle’s largely wooden superstructure was found to be the main cause of the fire’s rapid spread.”

Castle capsized onto her port side just before 6:00am and sank at 6:03am. The wreck has not been located but is thought to rest 10,800 feet below the Atlantic. “The Yarmouth Castle disaster prompted updates to the Safety of Life at Sea law, or SOLAS. The updated law brought new maritime safety rules, requiring fire drills, safety inspections, and structural changes to new ships. Under SOLAS, any vessel carrying more than 50 overnight passengers is required to be built entirely of non-combustible materials such as steel. Yarmouth Castle’s largely wooden superstructure was found to be the main cause of the fire’s rapid spread.”

Southend Pier, is the longest pier in the world. It is located in Southend-On-Sea, Essex, United Kingdom. It is famous for being the longest pier, but it is also famous for something else. It has a long history of…fires!! It wasn’t that there were so many fires, but rather that they occurred over a long period…40 years to be exact. That might not sound like such a big deal, which while sounding like a long period of time, is still rather unusual. The fires on the pier took place in 1959, 1976, 1995, and 2005.

Southend Pier, is the longest pier in the world. It is located in Southend-On-Sea, Essex, United Kingdom. It is famous for being the longest pier, but it is also famous for something else. It has a long history of…fires!! It wasn’t that there were so many fires, but rather that they occurred over a long period…40 years to be exact. That might not sound like such a big deal, which while sounding like a long period of time, is still rather unusual. The fires on the pier took place in 1959, 1976, 1995, and 2005.

Originally, the pier was really no more than a timber jetty. Then in 1829, a was passed to build the new pier. The bill received Royal Assent in May 1829 and construction started in July 1829. The original wooden pier that was finished in 1830, was just 600 feet long and probably nothing that could be considered spectacular. Over the years, the pier has evolved into an iron construction over a mile and a third in length. The history of the pier dating back well over a century, was one of developing facilities and increasing use by holidaymakers, with the exception of the World War II years. From 1939 to 1945 the pier was designated HMS Leigh and used as a mustering point for convoys and the location of Thames Estuary naval control staff.

All was going well, and then on October 7, 1959, disaster struck. In the evening a fire began in the Victorian pavilion towards the shore end of the pier. That part of the pier, a wooden structure went up like dried grass. At the time, there were between 300 and 500 visitors who were at the far end of the pier more than a mile away from the pavilion. It was a scary situation, because the visitors were required to walk toward the flames and then descend into waiting boats to be ferried back to the shore, bypassing the blaze. Of course, like any such incident, onlookers were provided with more than two hours of free entertainment, and since the pier was a popular attraction, there was a large crowd on the shore.

Because the pier was such a popular attraction, it was quickly repaired, and the pavilion was replaced with a bowling alley. While everyone thought everything was looking up, it was the start of a remarkable run of

disasters. More fires followed in 1976, 1995, and 2005 wreaking havoc on the pier. In addition, the MV Kingsabbey, a converted waste disposal carrier with a history of accidents crashed into the Southend pier in June 1984, smashing a 70-foot hole in the pier. The damage caused by that crash was not fully repaired until 1989.

disasters. More fires followed in 1976, 1995, and 2005 wreaking havoc on the pier. In addition, the MV Kingsabbey, a converted waste disposal carrier with a history of accidents crashed into the Southend pier in June 1984, smashing a 70-foot hole in the pier. The damage caused by that crash was not fully repaired until 1989.

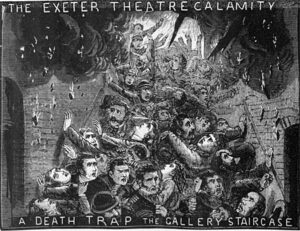

In American schools, and maybe in schools all over the world, children are used to the occasional fire drill, because it is a practice is designed to allow people to escape a fire, instead of losing their lives in a panic. Of course, this practice is fairly new, and came about after a number of fire disasters. One such disaster was the September 5, 1887, Exeter Theatre Royal fire in Exeter, England.

In American schools, and maybe in schools all over the world, children are used to the occasional fire drill, because it is a practice is designed to allow people to escape a fire, instead of losing their lives in a panic. Of course, this practice is fairly new, and came about after a number of fire disasters. One such disaster was the September 5, 1887, Exeter Theatre Royal fire in Exeter, England.

The fire broke out in the backstage area of the theatre during the production of “The Romany Rye” by George Robert Sims and produced by Wilson Barrett. When the fire was known, a panic ensued throughout the theatre. Whenever there is panic, someone is going to get hurt, or worse. In this case, 186 people died from a combination of the direct effects of smoke and flame, crushing and trampling, and trauma injuries from falling or jumping from the roof and balconies. It is such a sad situation, because if they had not panicked, it is likely that all or most of those would have survived. Of course, panic was not the only reason for the deaths, so we will never truly know if this could have been prevented. The Exeter Theatre Royal death toll makes it the worst theatre disaster, the worst single-building fire, and the third worst fire-related disaster in the history of the United Kingdom. Most of those who lost their lives were in the gallery of the theatre, which had only a single exit with several design flaws. The exit quickly became clogged with people trying to escape.

This was not the first time the Theatre Royal had been destroyed. The first Exeter Theatre Royal had been gutted by fire in 1885, and the new theatre was opened, on a new site, in 1886 to the design of well-known theatre architect CJ Phipps. The new theatre was leased exclusively to Sidney Herberte-Basing. The new  building was constructed from stone and red brick on the outside, but the inside was largely constructed of wood. Following the 1885 fire, the licensing authority of Exeter City Council ordered that the new theatre be constructed “in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Metropolitan Board of Works,” which was a statutory requirement in London under The Metropolitan Building Act 1855 (with theatre particulars added in the 1878 amendment), but not required in the regions. In his letter accompanying the plans to the Corporation Surveyor of Exeter City Council, Phipps directly states that the building met all the rules and requirements laid out, ans added that he had extensive experience in these types of construction. The letter stated, “…the theatre is designed in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Board of Works under the Act of 1878 and of the Lord Chamberlain – and having constructed some 40 theatres, I bring a somewhat large experience to bear on this subject.” – C.J. Phipps, Letter of 11 July 1885 from Phipps to the Corporation Surveyor of the City of Exeter.

building was constructed from stone and red brick on the outside, but the inside was largely constructed of wood. Following the 1885 fire, the licensing authority of Exeter City Council ordered that the new theatre be constructed “in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Metropolitan Board of Works,” which was a statutory requirement in London under The Metropolitan Building Act 1855 (with theatre particulars added in the 1878 amendment), but not required in the regions. In his letter accompanying the plans to the Corporation Surveyor of Exeter City Council, Phipps directly states that the building met all the rules and requirements laid out, ans added that he had extensive experience in these types of construction. The letter stated, “…the theatre is designed in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Board of Works under the Act of 1878 and of the Lord Chamberlain – and having constructed some 40 theatres, I bring a somewhat large experience to bear on this subject.” – C.J. Phipps, Letter of 11 July 1885 from Phipps to the Corporation Surveyor of the City of Exeter.

Nevertheless, during the licensing inspection, several deficiencies were noted and ordered to be corrected, including “installing an additional exit for the audience from the boxes, stalls, and pit, widening the exits to at  least 6 feet, changing some single leaf exit doors to double doors, and supplying 80 feet of hose for each hydrant (of which there were only two – one in the foyer and one in the “prompts” in front of the stage), rather than 40 feet which had been provided.” Unfortunately, there was no inspection of the stage, the mezzanine floor, or the fly galleries above the stage. There was only one exit with four right angled turns in it, from this area, and while two exits were called for, the idea was passed over because Phipps asserted “that a second exit was provided by climbing the railing at the front of the gallery and dropping to the second circle below.” That was, of course a crazy notion, that cost lives in the end. Apparently, this plan was accepted without further argument. In addition, there was to be an iron safety curtain, which was not fitted at the time of the fire, and a fire hydrant in the stage wings was on the plans of the theatre but never installed, despite Phipps being advised that the two hydrants installed were insufficient. In the end, the panic, along with the mishandled inspections and the improper plan design cost 186 people their lives.

least 6 feet, changing some single leaf exit doors to double doors, and supplying 80 feet of hose for each hydrant (of which there were only two – one in the foyer and one in the “prompts” in front of the stage), rather than 40 feet which had been provided.” Unfortunately, there was no inspection of the stage, the mezzanine floor, or the fly galleries above the stage. There was only one exit with four right angled turns in it, from this area, and while two exits were called for, the idea was passed over because Phipps asserted “that a second exit was provided by climbing the railing at the front of the gallery and dropping to the second circle below.” That was, of course a crazy notion, that cost lives in the end. Apparently, this plan was accepted without further argument. In addition, there was to be an iron safety curtain, which was not fitted at the time of the fire, and a fire hydrant in the stage wings was on the plans of the theatre but never installed, despite Phipps being advised that the two hydrants installed were insufficient. In the end, the panic, along with the mishandled inspections and the improper plan design cost 186 people their lives.

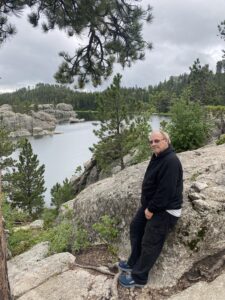

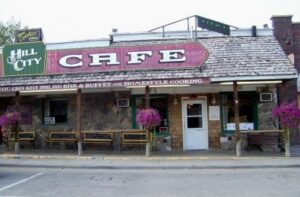

While my husband, Bob and I were in the Black Hills last week, we were having breakfast at the Hill City Cafe, when we overheard a waitress telling another table the story of how the Hill City High School came to have Smokey Bear as their mascot and be renamed the Hill City Rangers. I had no idea that anyone used Smokey Bear as their mascot, nor did I know that no other school was allowed to do so. That caught my interest, so we listened to the story, and then I had to research it further to get the whole story. And quite a story it is.

While my husband, Bob and I were in the Black Hills last week, we were having breakfast at the Hill City Cafe, when we overheard a waitress telling another table the story of how the Hill City High School came to have Smokey Bear as their mascot and be renamed the Hill City Rangers. I had no idea that anyone used Smokey Bear as their mascot, nor did I know that no other school was allowed to do so. That caught my interest, so we listened to the story, and then I had to research it further to get the whole story. And quite a story it is.

It all started around noon on July 10, 1939, with one of the worst forest fires in the history of the Black Hills. It was located just ten miles northwest of Hill City, and that’s too close for any wildfire to be to a city. Overnight, the fire burned through six of those ten miles, jumped the Mystic Road, the C.B. and Q. Railway, and was headed directly for Hill City. These are areas my husband, Bob and I have hiked, and hearing about the fire raging through them really hits home for me. The C.B. and Q Railway (Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy Railroad) was later abandoned and became the Mickelson Trail, which I have hiked from end to end, twice!! Not in one trip, but over about 10 years, one section at a time. The whole area is a place I love, and to think of it burning…well, it tears at my heart.

By noon on July 11, 1939, the fire was within three miles of town. That was when the wind changed and carried the fire further North and East. Still, Hill City and other towns were not safe, winds shift all the time, and the fire had to be stopped. The weather that year had been hot and very dry, unlike this year, plus a high wind repeatedly “crowned” the fire. The firefighters were in constant danger. They had already called in all of the Civilian Conservation Corps boys in the area, who had been immediately put on the fire, and now the forest rangers called for more help. You know that the situation is desperate, when they call for untrained volunteers. Shockingly, one of the first crews to respond was a group of 25 schoolboys from Hill City. These were high school kids…kids!! The crew of 25 included the entire basketball squad, one eighth grader, and several boys

who had recently attended or graduated from the Hill City High School. Their foreman was Charles Hare, President of the Board of Education. This whole story of bravery and selflessness brings tears to my eyes and puts a lump in my throat.

who had recently attended or graduated from the Hill City High School. Their foreman was Charles Hare, President of the Board of Education. This whole story of bravery and selflessness brings tears to my eyes and puts a lump in my throat.

The inferno raged throughout July 11th and into July 12th and utilized over four thousand firefighters, laboring together to bring the fire under control. The fire often isolated the crews, who went without food and water for a number of hours. Heat, smoke, and the danger of being trapped hampered the firefighters, but the blaze was brought under control on July 12th. The people of Hill City had spent many anxious hours watching the smoke and direction of the fire. Many had packed their belongings and were ready to move, but the order to abandon the town was never given. The schoolboys crew from Hill City was at the fire every day. The US Forest Service was so grateful to them that they were later recognized by officials as one of the best crews!! The McVey Fire burned over 20,000 acres.

To get back to the story the waitress was so proudly telling, “The name ‘Rangers’ was given to them in honor of their good record. Because of the work of these schoolboys back in 1939, Hill City Schools became the ONLY school district in the United States to have the privilege of using ‘Smokey Bear’ as its mascot. The school colors are Green and Gold which also represent the National Forest Service Theme, and Hill City is the ONLY school with the honorable privilege of having their graduation ceremonies held at Mount Rushmore. The staff, students and teams representing Hill City Schools hope to continue the traditions of the splendid group of men that our boys so ably assisted, The United States Forest Rangers.” It’s a proud tradition to own, and an awesome goal to

reach for. I’m sure they will be able to achieve their goal, and as an annual “tourist” in the area, who loves the Black Hills, I want to thank all the brave firefighters in the Black Hills-Hill City area…past, present, and future (one of which was my niece, Lindsay Moore, for a summer) for all their hard work keeping the area safe, and mostly for their bravery.

reach for. I’m sure they will be able to achieve their goal, and as an annual “tourist” in the area, who loves the Black Hills, I want to thank all the brave firefighters in the Black Hills-Hill City area…past, present, and future (one of which was my niece, Lindsay Moore, for a summer) for all their hard work keeping the area safe, and mostly for their bravery.

Hiking and Backpacking have been a favorite pastime for many people for many years, and some people go to greater lengths and distances than others. Backpacking in Australia is a trip on the bucket lists of a lot of people. On their hikes, many people have made the Childers Palace Backpackers Hostel one of their stops. Located in the former Palace Hotel in the town of Childers, Queensland, Australia, the building had been converted into a backpacker hostel. That was the stop for 15 backpackers on June 22, 2000. They had been hiking all day and were ready for some downtime. After a relaxed evening, they all went to bed. There were 88 people staying in the building that night, but the building could house 101 people.

Hiking and Backpacking have been a favorite pastime for many people for many years, and some people go to greater lengths and distances than others. Backpacking in Australia is a trip on the bucket lists of a lot of people. On their hikes, many people have made the Childers Palace Backpackers Hostel one of their stops. Located in the former Palace Hotel in the town of Childers, Queensland, Australia, the building had been converted into a backpacker hostel. That was the stop for 15 backpackers on June 22, 2000. They had been hiking all day and were ready for some downtime. After a relaxed evening, they all went to bed. There were 88 people staying in the building that night, but the building could house 101 people.

At about 12:30am on June 23, 2000, a fire started in the downstairs recreation room and quickly spread up the walls and into the stairwell. The first emergency call came from a pay phone across the street, and it was logged at 12:31am. Emergency services first arrived at 12:38am and spent four hours battling the fire before it was fully extinguished. In the aftermath, it was found that 15 backpackers, nine women and six men, had lost their lives. Survivors told of how smoke quickly filled the area and how the building’s power was lost. They struggled in the darkness to find a way out, and in the absence of alarms and emergency lighting, some people attempted to awaken and rescue as many people as they could. Of the 70 backpackers who survived the fire, 10 suffered minor burns and injuries as they tried to escape from the upper level and by jumping onto the roofs of the neighboring buildings. In this fire, those who got out lived, those who died did not get out at all.

Of the 15 who died in the fire, seven were British, three were Australian, two were from the Netherlands, and one each from Ireland, Japan, and South Korea. It took a while to identify the dead, because there was an incomplete hostel register. It recorded check-ins, but unfortunately not departures. To further complicate things, most of the residents’ passports were destroyed or damaged by the fire. DNA samples were also difficult to obtain for those with no relatives in Australia. Most of the backpackers who died were on the first floor of the hostel. Through an inquest, it was found that in one of the upper rooms where 10 victims were found, which was all of the occupants of that room, a bunk bed blocked a fastened exit door, and the windows were barred. They had little chance of escape.

It was found that a fruit packer named Robert Paul Long, had moved into the hostel on March 24, 2000, but had been evicted on June 14, 2000, over a matter of $200 rent in arrears. Long didn’t leave the area, as was seen in ATM records that showed him in the area in the week before the fire. Long, who had expressed a hatred of backpackers, had also earlier threatened to burn down the hostel. Around midnight, prior to the fire, two guests saw Long in the back yard of the hostel. Long had asked them to leave the door open so he could assault his former roommate, an Indian national. They declined, and he told them that he still had a key. Another guest recounted how he had woken up around midnight to find Long downstairs using a PC near a burning rubbish bin. After the guest protested the reckless actions, Long took the bin outside, and the guest went back to bed, but was awakened later to banging sounds, shouting, and thick black smoke.

After the fire, Long tried to mask his movements, but he was later spotted in cane-fields about five days later. At that time, he was arrested in bush-land near Howard, which is less than 20 miles from Childers. As he was being arrested, Long stabbed a police dog after being bitten. Then, he stabbed one of the officers in the jaw and the second officer shot Long in the shoulder. In March of 2002, Long was found guilty of two charges of murder (for the dead Australian twins) and arson and sentenced to life in prison. While it seems strange to only charge him with the deaths of two of the 15 victims, it was thought that it would expedite the proceedings and to allow for other charges to be brought in the event of an acquittal. Following his conviction, Long filed an appeal in 2002, which was denied. In June 2020 he became eligible for parole, but his February 2021 parole appeal was rejected. He could become eligible again in 1 year.

After the fire, and many people losing everything they owned, survivors were temporarily housed locally at the Isis Cultural Centre. Japan’s embassy officials quickly evacuated five Japanese nationals, which eased things a little. Residents of Childers knitted blankets and donated food and backpacks for the survivors. Residents also invited survivors for meals and showers and local businesses assisted with food, clothing, and personal items. Media, politicians, and investigators came to the site as well and Princess Anne visited on July 2nd, to meet the surviving backpackers and others involved in the disaster.

The results of a coronial inquest were released in 2006. “The hostel, a 98-year-old, two-story timber building, did not have working smoke detectors or fire alarms. It was later reported that the owner had installed fire alarms in the building, but they had been disabled weeks prior to the fire due to regular malfunctioning. It was also mentioned that batteries for the stand-alone alarms were sometimes removed by customers for portable cameras or music players.” When it was announced that the coroner had decided not to charge the owner and operators of the hostel for negligence, families of seven victims filed a class action suit against them.

On October 26, 2002, the renovated structure, renamed the Palace Memorial Building, opened and the opening ceremony was attended by some 250 invited guests, including members of 12 of the families of those who died. Frank Slarke, the father of the dead Australian twins, read a poem he wrote as a eulogy. Since then, over one million visitors have visited the building.

On October 26, 2002, the renovated structure, renamed the Palace Memorial Building, opened and the opening ceremony was attended by some 250 invited guests, including members of 12 of the families of those who died. Frank Slarke, the father of the dead Australian twins, read a poem he wrote as a eulogy. Since then, over one million visitors have visited the building.

Captain John Mason was an English-born settler, soldier, commander, and Deputy Governor of the Connecticut Colony. While most people want to be remembered for the great things they did during their lives, Captain Mason will always be remembered for something else…being the leader of the massacre of the Pequot Tribe of Native Americans in southeast Connecticut. The group, led by Mason was a group of Puritan settlers and Indian allies, who combined to attack a Pequot Fort in an event known as the Mystic Massacre. The Mystic Massacre took place on May 26, 1637, during the Pequot War, when Connecticut colonizers and their Narragansett and Mohegan allies set fire to the Pequot Fort near the Mystic River. With the fire raging, they shot anyone who tried to escape the wooden palisade fortress, effectively murdering most of the village. In all, there were between 400 and 700 Pequot civilians killed during the massacre. The only Pequot survivors were warriors who were away in a raiding party with their sachem (chief), Sassacus.

Captain John Mason was an English-born settler, soldier, commander, and Deputy Governor of the Connecticut Colony. While most people want to be remembered for the great things they did during their lives, Captain Mason will always be remembered for something else…being the leader of the massacre of the Pequot Tribe of Native Americans in southeast Connecticut. The group, led by Mason was a group of Puritan settlers and Indian allies, who combined to attack a Pequot Fort in an event known as the Mystic Massacre. The Mystic Massacre took place on May 26, 1637, during the Pequot War, when Connecticut colonizers and their Narragansett and Mohegan allies set fire to the Pequot Fort near the Mystic River. With the fire raging, they shot anyone who tried to escape the wooden palisade fortress, effectively murdering most of the village. In all, there were between 400 and 700 Pequot civilians killed during the massacre. The only Pequot survivors were warriors who were away in a raiding party with their sachem (chief), Sassacus.

Prior to the massacre, the Pequot tribe were the dominate Native American tribe in southeast Connecticut, but  with the massacre, came the end of an era where that was concerned. The massacre was brutal and heinous and should have been met with severe punishment, but at that time in history, the Native Americans were not particularly valued among the people of the colonies. In fact, the Native Americans were probably viewed as the intruders, and not the natives. As more and more Puritans from Massachusetts Bay spread into Connecticut, the conflicts with the Pequots increased. The tribe centered on the Thames River in southeastern Connecticut, and by the spring of 1637, the Pequot tribe killed 13 English colonists and traders. That was when Massachusetts Bay Governor John Endecott organized a large military force to punish the Indians, who were only trying to protect what they saw as theirs. On April 23, 1637, with pressure mounting, 200 Pequot warriors responded defiantly to the colonial mobilization by attacking a Connecticut settlement, killing six men and three women and taking two girls away.

with the massacre, came the end of an era where that was concerned. The massacre was brutal and heinous and should have been met with severe punishment, but at that time in history, the Native Americans were not particularly valued among the people of the colonies. In fact, the Native Americans were probably viewed as the intruders, and not the natives. As more and more Puritans from Massachusetts Bay spread into Connecticut, the conflicts with the Pequots increased. The tribe centered on the Thames River in southeastern Connecticut, and by the spring of 1637, the Pequot tribe killed 13 English colonists and traders. That was when Massachusetts Bay Governor John Endecott organized a large military force to punish the Indians, who were only trying to protect what they saw as theirs. On April 23, 1637, with pressure mounting, 200 Pequot warriors responded defiantly to the colonial mobilization by attacking a Connecticut settlement, killing six men and three women and taking two girls away.

Then on May 26, 1637, everything exploded when, two hours before dawn, the Puritans and their Indian allies marched on the Pequot village at Mystic, slaughtering all but a handful of its inhabitants. Following that attack, Captain Mason attacked another Pequot village on June 5, 1637, this one near what is now Stonington, and again the Indian defenseless inhabitants, were defeated and massacred. In a third attack on July 28, 1637, Mason and his men massacred a village near what is now Fairfield, and the Pequot War finally came to an end. Most of the surviving Pequot were sold into slavery, though a handful escaped to join other southern New England tribes.

Then on May 26, 1637, everything exploded when, two hours before dawn, the Puritans and their Indian allies marched on the Pequot village at Mystic, slaughtering all but a handful of its inhabitants. Following that attack, Captain Mason attacked another Pequot village on June 5, 1637, this one near what is now Stonington, and again the Indian defenseless inhabitants, were defeated and massacred. In a third attack on July 28, 1637, Mason and his men massacred a village near what is now Fairfield, and the Pequot War finally came to an end. Most of the surviving Pequot were sold into slavery, though a handful escaped to join other southern New England tribes.

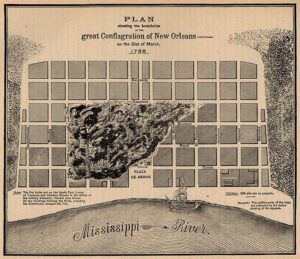

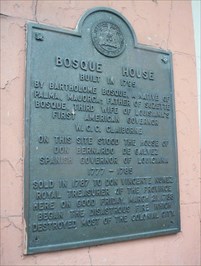

I don’t know what kind of a city New Orleans was in 1788, but much of it changed that year, because on March 21, 1788, the first of two great fires left the city in ruins. There are a number of ways to destroy a city…time, storms, neglect, need, and the worst one, fire. Were it not for two great fires, there might be more of colonial New Orleans left for people to enjoy. Unfortunately, two great fires in the late eighteenth century left New Orleans and its inhabitants very few years to re-establish their institutions before the onset of American domination in 1803, making the city more American than French. Today, there are several fine houses that date to the last colonial decade, as well as the French Quarter, including the Cabildo and the Presbytere, but they are “post-fire” nevertheless.

I don’t know what kind of a city New Orleans was in 1788, but much of it changed that year, because on March 21, 1788, the first of two great fires left the city in ruins. There are a number of ways to destroy a city…time, storms, neglect, need, and the worst one, fire. Were it not for two great fires, there might be more of colonial New Orleans left for people to enjoy. Unfortunately, two great fires in the late eighteenth century left New Orleans and its inhabitants very few years to re-establish their institutions before the onset of American domination in 1803, making the city more American than French. Today, there are several fine houses that date to the last colonial decade, as well as the French Quarter, including the Cabildo and the Presbytere, but they are “post-fire” nevertheless.

The French Quarter of today is very different from what it once was, and it makes me wonder what it might have been like before. These days, the French Quarter receives millions of visitors annually, and it’s hard to imagine the carnage of the fire of Holy Saturday morning in 1788. The fire was devastating, with smoking ruins stretching from Chartres to Dauphine Street, and from Conti to Saint Philip. The fire actually began on Good Friday morning in the home of Spanish treasurer Don Vincente Nunez at Toulouse and Chartres. The wind was blowing out of the southeast bringing in a blustery cold front. The wind, combined with the fire, reduced over eight hundred homes and public buildings to ashes in a matter of hours. The church, the town hall, and the rectory on the Plaza de Armas were suddenly gone. Governor Esteban Miro told Spanish authorities of the “abject misery, crying, and sobbing” of the people. He wrote that the faces of the families, “told the ruin of a city which in less than five hours has been transformed into an arid and horrible wilderness; the work of seventy years since its foundation.”

The rebuilding of the city began right away, but had barely started when, in 1794 a second fire and two hurricanes swept the city. It seemed that New Orleans was doomed to devastation. The December 8, 1794, fire burned 212 buildings…fewer than the prior fire, but these buildings were more valuable. After the two storms and both fires were done, nearly all the public buildings, homes and businesses, except those fronting the river had been reduced to ashes or badly damaged. Through it all the Ursuline nuns in their convent on Chartres Street had prayed over their hometown, and as the fire got close to the convent on that Good Friday, the wind suddenly shifted. Miraculously, the convent survived and still stands today.

The French Quarter was essentially changed forever. “Baked tile and quarried slate replaced the roofs of ax-hewn cypress shingles. Buildings, set at the sidewalk or banquette, were of all brick, with common firewalls. The wide and shallow hipped roof, galleried townhouse perfected in the French period gave way to vertical, long and narrow Spanish-style town homes, many with overhangs, iron work and entresols or mezzanines. The Cabildo and Presbytere came into being. A new church rose from the ashes. A suburb opened on the upper side of town for residents wary of crowded Quarter conditions. Fire pumps were commissioned. The market moved riverside. Artisans were called in. Protestants gained a foothold. But people went homeless, the city indebted, and lives were lost to death or removal. The city was different.”

Since 1794, the French Quarter has been spared large fires, although there have been some smaller fires, and the hurricanes kept coming. They are just common to the area. A great storm that took place on August 19, 1812, swept away a one-year-old French Market building. Another in 1915 damaged the steeple of Saint Louis Cathedral. A fire in September 1816 took the popular Orleans Theater and Orleans Ballroom. Then, the rebuilt theater burned again in 1866. Fire damaged the Bank of Louisiana on Royal Street resulting in the monumental columns installed in the remodeling, which is now the home of the Vieux Carré Commission.

These devastating losses have resulted in a stringent French Quarter fire code. No longer is the Mardi Gras

parade allowed to be motorized. The city takes prevention very seriously, knowing that fire spreading would be devastating to the French Quarter and to the city as a whole. Even with every precaution, the most important fires of the Twentieth Century occurred at individual structures. It is thought, by some historians, that the burning of the Old French Opera House on Bourbon, in 1919, was the “final nail” in the coffin of the old Creole culture in the Quarter, while others adopted that culture, thereby keeping its memory alive. Then, when the Cabildo burned in 1988, two hundred years after the First Great Fire, the citizens of the city felt the loss deeply. The structure was carefully restored, and it stands as a proud reminder of a city’s resolve to safeguard its heritage to this day.

parade allowed to be motorized. The city takes prevention very seriously, knowing that fire spreading would be devastating to the French Quarter and to the city as a whole. Even with every precaution, the most important fires of the Twentieth Century occurred at individual structures. It is thought, by some historians, that the burning of the Old French Opera House on Bourbon, in 1919, was the “final nail” in the coffin of the old Creole culture in the Quarter, while others adopted that culture, thereby keeping its memory alive. Then, when the Cabildo burned in 1988, two hundred years after the First Great Fire, the citizens of the city felt the loss deeply. The structure was carefully restored, and it stands as a proud reminder of a city’s resolve to safeguard its heritage to this day.

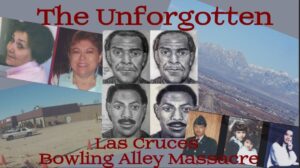

Evil can be just around the corner, and sadly, sometimes, the evil doers walk away without being punished for their crimes. On the morning of February 10, 1990, the staff at Las Cruces Bowl were busy getting ready for the Saturday bowling crowd, when two armed men walked in through an unlocked door. The men were there to rob the place. They could have worn masks, or they could have just robbed the place and fled the scene, but they had no intention of being caught, and that meant that they couldn’t leave witnesses.

Evil can be just around the corner, and sadly, sometimes, the evil doers walk away without being punished for their crimes. On the morning of February 10, 1990, the staff at Las Cruces Bowl were busy getting ready for the Saturday bowling crowd, when two armed men walked in through an unlocked door. The men were there to rob the place. They could have worn masks, or they could have just robbed the place and fled the scene, but they had no intention of being caught, and that meant that they couldn’t leave witnesses.

Stephanie C Senac, 34, who was the bowling alley manager, was in her office preparing to open the for the day. Her 12-year-old daughter Melissa Repass and Melissa’s 13-year-old friend Amy Houser were there to supervise the alley’s day care. The gunmen took them into the office, where they robbed them of a mere $4,000 to $5,000. As robberies go, it was practically nothing. When bowling alley mechanic Steven Teran came in with his two young daughters, Paula Holguin and Valerie Teran, they were totally unprepared for what faced them. Teran was unable to find a  babysitter for his daughters that day, so he had decided that he would drop them at the bowling alley daycare for the Melissa and Amy to watch. As the robbers took cash from the safe, the seven unfortunate people, including Teran and his daughters; cook Ida Holguin (no relation to Paula); manager Stephanie Senac, her daughter, and her daughter’s friend tried to be cooperative in the hope of making it out alive, but the men told them to get down on the ground. Then they shot all of the victims multiple times at close range, aiming mostly for their heads. When the shooting was over, they were still not satisfied with how things stood, so they set fire to some papers in the office of the bowling alley and left.

babysitter for his daughters that day, so he had decided that he would drop them at the bowling alley daycare for the Melissa and Amy to watch. As the robbers took cash from the safe, the seven unfortunate people, including Teran and his daughters; cook Ida Holguin (no relation to Paula); manager Stephanie Senac, her daughter, and her daughter’s friend tried to be cooperative in the hope of making it out alive, but the men told them to get down on the ground. Then they shot all of the victims multiple times at close range, aiming mostly for their heads. When the shooting was over, they were still not satisfied with how things stood, so they set fire to some papers in the office of the bowling alley and left.

Miraculously, Ida, Senac, and Melissa all survived. Melissa, despite being shot five times, was able to call 911. Unfortunately, the fire and subsequent efforts to put out the fire destroyed most of the evidence. In those days, forensics mostly involved fingerprints, which were in abundance in the bowling alley. DNA was not really as  developed at that time. Investigators were unable to discern which fingerprints were meaningful. There were witnesses, of course, who identified the suspects as two Hispanic men, in their 30s or 40s. Roadblocks were quickly set up by the police, to screen anyone leaving town. Still, the suspects were never found. Despite a frequent stream of tips, authorities are no closer to identifying and arresting the suspects today than they were 32 years ago…even with age enhanced pictures. The murders have been shown on multiple crime solving programs, including on Unsolved Mysteries two and a half months after the murders, and on America’s Most Wanted twice, once in November 2004 and again in March 2010. In the end, the crime also took the life of Stephanie Senac, who died in 1999…nine years later, due to complications from her injuries. The men got away with just $4,000 to $5,000, but the victims paid dearly.

developed at that time. Investigators were unable to discern which fingerprints were meaningful. There were witnesses, of course, who identified the suspects as two Hispanic men, in their 30s or 40s. Roadblocks were quickly set up by the police, to screen anyone leaving town. Still, the suspects were never found. Despite a frequent stream of tips, authorities are no closer to identifying and arresting the suspects today than they were 32 years ago…even with age enhanced pictures. The murders have been shown on multiple crime solving programs, including on Unsolved Mysteries two and a half months after the murders, and on America’s Most Wanted twice, once in November 2004 and again in March 2010. In the end, the crime also took the life of Stephanie Senac, who died in 1999…nine years later, due to complications from her injuries. The men got away with just $4,000 to $5,000, but the victims paid dearly.