fire

I think most people have heard of Big Ben, the famous clock tower in London, but what you may not know is that originally, there was no clock and no tower. The Houses of Parliament and Elizabeth Tower, most often called Big Ben, are among London’s most iconic landmarks and favorite London attractions. Big Ben is actually the name that was given to the massive bell inside the clock tower, which weighs more than 13 tons, not to the clock or the tower. At night the four clock faces are illuminated, and the effect is spectacular.

I think most people have heard of Big Ben, the famous clock tower in London, but what you may not know is that originally, there was no clock and no tower. The Houses of Parliament and Elizabeth Tower, most often called Big Ben, are among London’s most iconic landmarks and favorite London attractions. Big Ben is actually the name that was given to the massive bell inside the clock tower, which weighs more than 13 tons, not to the clock or the tower. At night the four clock faces are illuminated, and the effect is spectacular.

The British Parliament is located in the Palace of Westminster. In October of 1834, a fire destroyed much of the palace and it had to be rebuilt. At that time it was decided that there would be an spectacular addition of a clock at the top of a tower. The clock is magnificent. Each dial measures almost 23 feet in diameter. The hands are 14 feet long and weigh about 220 pounds, including counterweights. The numbers on the clock’s face are approximately 23 inches long. There are 312 pieces of glass in each clock dial. When parliament is in session, a special light above the clock faces is illuminated. Big Ben’s timekeeping is strictly regulated by a stack of coins placed on the huge pendulum. Big Ben has rarely stopped. Even after a bomb destroyed the Commons chamber during World War II, the clock tower survived and Big Ben continued to strike the hours. The chimes of Big Ben were first broadcast by the BBC on December 31, 1923. It is a tradition that continues to this day. The Latin words under the clock face read Domine Salvam Fac Reginam Nostram Victoriam Primam, which means “O Lord, keep safe our Queen Victoria the First.” In June 2012 the House of Commons announced that the clock tower was to be renamed the Elizabeth Tower in honor of Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee.

A massive bell was required and the first attempt made by John Warner and Sons at Stockton-On-Tees cracked irreparably. Big Ben first rang across Westminster on May 31, 1859. A short time later, in September 1859, Big

Ben cracked. The metal was melted down and the bell recast in Whitechapel in 1858. A lighter hammer was fitted and the bell rotated to present an undamaged section to the hammer. This is the bell as we hear it today, and the real owner of the name Big Ben. Elizabeth Tower stands at more than 105 yards tall, with 334 steps to climb up to the belfry and 399 steps to the Ayrton Light at the very top of the tower.

Ben cracked. The metal was melted down and the bell recast in Whitechapel in 1858. A lighter hammer was fitted and the bell rotated to present an undamaged section to the hammer. This is the bell as we hear it today, and the real owner of the name Big Ben. Elizabeth Tower stands at more than 105 yards tall, with 334 steps to climb up to the belfry and 399 steps to the Ayrton Light at the very top of the tower.

A fire always draws crowds of spectators, and the crowds that gathered at New York City’s pier 88 on February 9, 1942 were no different. The billowing smoke drew their attention, and they were witness to the fire, and in the end, the loss of the SS Normandie…the largest ocean liner in the world at that time. Valiant fire fighting efforts successfully contained the fire after five and a half hours, but the effort was in vain. Five hours after the flames were out the SS Normandie rolled onto its side and settled on the bottom of the Hudson River.

A fire always draws crowds of spectators, and the crowds that gathered at New York City’s pier 88 on February 9, 1942 were no different. The billowing smoke drew their attention, and they were witness to the fire, and in the end, the loss of the SS Normandie…the largest ocean liner in the world at that time. Valiant fire fighting efforts successfully contained the fire after five and a half hours, but the effort was in vain. Five hours after the flames were out the SS Normandie rolled onto its side and settled on the bottom of the Hudson River.

The SS Normandie was intended to be the pride of the French people. The ship was designed to be the height of shipbuilding technology and modern culture. The first class passenger spaces were decorated in the trendiest Art Deco style and filled with all the latest luxuries. The radical new hull design, with a subsurface bulb beneath a clipper bow, and long, sweeping lines gave her previously untouched speeds, while requiring far less fuel. In order to improve the safety for the passengers, the ship even had one of the earliest radar sets ever used by a commercial vessel.

Still, with all of Normandie’s modern touches, there was to be no salvation for the great ship. The Normandie was put into service during the height of the Great Depression. A sign of her future, seemed to predict trouble when, on launching, the wave she kicked up smashed into hundreds of onlookers, though no one was injured in this accident. The ship performed spectacularly during trials, but would never prove to be a particularly successful ship, only making just enough to cover her operating expenses and never paying for the loans needed to finance her construction. The French declaration of war on Germany in September 1939 found the Normandie in New York, tied up alongside of pier 88. In spite of the loss of 28 American lives when a German u-boat torpedoed the Athenia on the first day of hostilities, the United States remained neutral. Nevertheless, authorities immediately put Coast Guard troops on board the Normandie and interned her in accordance with international maritime law. Though the French crew would remain aboard maintaining the vessel, she had to remain beside the pier, guarded by the Coast Guard, for two long years until the United States entered into the war. Five days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the French crew were removed from Normandie. France was technically a German ally under the Vichy government, and as such the US government exercised the right to  seize the ship as belonging to an enemy nation. The ship was renamed the USS Lafayette, in honor of the French General who had helped make the United States independence possible during the revolution. The US Navy took possession of the vessel and began her conversion as a troop transport.

seize the ship as belonging to an enemy nation. The ship was renamed the USS Lafayette, in honor of the French General who had helped make the United States independence possible during the revolution. The US Navy took possession of the vessel and began her conversion as a troop transport.

The conversion was a rushed job, as the ship was intended to set sail under the US flag on the 14th of February, 1942. However, given the size of the ship, and the complexity of its design, it proved a to be a substantial hindrance to the men performing the conversion. By February 6th, it was clear that the conversion would not be completed on time, and the conversion crew requested that the sail date be pushed back two weeks. The request was denied, and the frazzled crew rushed into a frantic effort to complete the work on time. Tragically, this forced haste set up the conditions for a disaster. Work spaces were not properly cleaned or prepared for lack of time to do it, and unsafe conditions became the norm. At 2:30 PM on February 9th, a welder in the first class lounge was performing work next to life preservers that should have been moved ahead of time. The sparks ignited the life preservers. The ship’s modern firefighting system should have prevented the tragedy, but it had been disabled during the conversion and was unavailable to be brought back online. The New York Fire Department responded within 15 minutes, but were horrified to learn the French fittings on the Normandie/Lafayette were not compatible with their hoses. Less than an hour after the fire broke out, the ship was a raging inferno. To help fight the blaze firefighters employed fire boats on the port side of the ship, while firefighters used dockside hoses to tackle the flames on the starboard side. The fight to put out the fires took over five hours, but ultimately it was a success. The fire was declared out by 8:00 PM that evening.

Unfortunately, they realized that they now had a new problem. The fire boats attacking the port side blaze pumped water at a far greater volume than was used by the dockside hoses on the starboard side. The Normandie/Lafayette was listing heavily to Port, submerging a number of open portholes on that side. The Navy attempted to counterflood to right the list, pumping water into the starboard side so that the ship would settle evenly, but It was too late. At a quarter till three, the Lafayette rolled over on her side and settled into the mud at the bottom of the Hudson River. The fire injured 285, with injuries ranging from smoke inhalation to burns. One Brooklyn native, Frank Trentacosta, died in the tragedy. The Normandie remained on the bottom for a year and a half, before finally being righted and floated in August of 1943. It was determined to be too badly damaged to be salvageable, and was sold and broken up for scrap in 1946.

The loss of the Normandie alongside of New York’s pier 88 signaled the end of an era. While ocean liners would remain the principle means to cross the Atlantic until commercial jet liners became available. Nevertheless,

very few ocean liners would be constructed in the post war period. None of these ships would approach either the speed or size of the Normandie. The last dedicated ocean liner to be constructed, the Queen Elizabeth II would hit the water in 1969. Most liners would eventually be removed from service to be converted into cruise liners for tourist jaunts, though a few stubborn holdouts would remain. Today only one ship continues to run the route of the old ocean liners. Constructed as a cruise ship, the Queen Mary II was launched in 2003 as a means by which tourists can attempt to recapture the experiences of the luxurious passages the Normandie had been constructed to provide in days gone by.

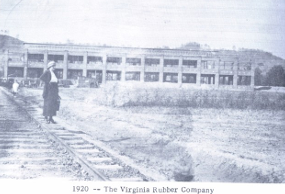

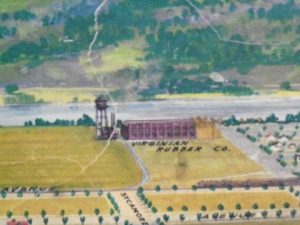

Several hundred people were employed by the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company in Saint Albans, West Virginia, on January 13, 1924. The business, located on 41 acres of land along the Kanawha River across from the present-day Ordnance Park (ca. 1941)…and before MacCorkle Avenue, was thriving in 1924. Established in 1920, it was only four years old. Unfortunately, the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company, was destined not to reach it’s fifth year. That fateful January day in 1924, brought with it a fire that destroyed the company, causing damage totaling $500,000.

Several hundred people were employed by the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company in Saint Albans, West Virginia, on January 13, 1924. The business, located on 41 acres of land along the Kanawha River across from the present-day Ordnance Park (ca. 1941)…and before MacCorkle Avenue, was thriving in 1924. Established in 1920, it was only four years old. Unfortunately, the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company, was destined not to reach it’s fifth year. That fateful January day in 1924, brought with it a fire that destroyed the company, causing damage totaling $500,000.

While I was unable to find much information as to the time and cause of the fire, it is noted that only about 10 percent of the tire stock was saved, and the rest was burned. That isn’t really surprising, since rubber tires are highly flammable. Unfortunately, it also doesn’t appear that all of the loss was covered by the company’s insurance. As an insurance agent, I can say that a property loss that was not completely covered by insurance could only mean that the company was underinsured, leaving gaps in the coverage. What is known about the loss is that the unpaid portion was enough to ensure that the company could never open their doors again. That meant that several hundred people were out of a job, and while they didn’t know it, the Great Depression was coming up quickly. I’m sure they all had jobs before that time, but it was quite likely that they would lose their jobs when that  time came.

time came.

The good news about the fire was that it took no lives. The only loss was to the property. Nevertheless, the town would never be quite the same again. Other businesses would grow up where the rubber company had once been, but mostly it would be remembered as the site of Morgan’s Plantation Kitchen, originally established in 1846. I supposed the site went back to it’s former identity. Still, the total loss of the Virginia Rubber and Tire Company, manufacturer of tires, tubes, toy balloons, balls, and rubber dolls, would not be forgotten.

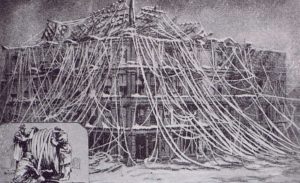

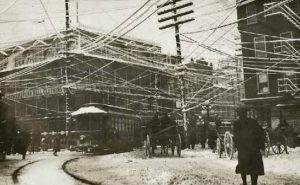

Sometimes, a picture can instill such a strange awareness within us that it is hard to get the picture out of our heads. It doesn’t have to be something horrible, bloody, or shocking, but simply something unusual. The phone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, built in 1887 is that kind of a picture, for sure.

Sometimes, a picture can instill such a strange awareness within us that it is hard to get the picture out of our heads. It doesn’t have to be something horrible, bloody, or shocking, but simply something unusual. The phone tower in Stockholm, Sweden, built in 1887 is that kind of a picture, for sure.

Technology has changed so much over the years, and this tower was a relic of the past. That is probably why the image has stuck in my head all this time. The tower served its purpose at the time, connecting 5,000 telephone wires and providing service to all those people, but to me it seemed rather dangerous in many ways. The telephone was an amazing invention, but somehow, the idea of buried cable never occurred to the inventor or the engineers who made it a reality for everyone. The service was very expensive, and so only for the wealthy…a fact that would change in years to come.

Similar towers sprang up around the world, and most residents soon grew to hate the massive amounts of lines that littered their skyline. Still, it was the only way at the time, and the telephone was, after all, an important invention. Too bad they couldn’t immediately come up with the wireless version we all enjoy these days. The telephone towers were used shortly before telephone companies started burying their wires in about 1913.

The change was well received, since most residents hated it, and some of the work was done after a snowstorm downed telephone poles, causing the cities to pay for the changes. Soon the hated phone lines began to disappear. I can see why the towers are hated, and to this day, most photographers hate to have the towers

and wires in their photographs. I have often found myself wishing the wires were missing from that perfect shot I got as my husband and I walked along the walking paths in Casper, so I can understand the way the residents of Stockholm, New York, and Boston felt about the monstrosity that was the telephone lines in their cities. Thankfully for the residents, the problem was solved when the tower burned down on July 25, 1953.

and wires in their photographs. I have often found myself wishing the wires were missing from that perfect shot I got as my husband and I walked along the walking paths in Casper, so I can understand the way the residents of Stockholm, New York, and Boston felt about the monstrosity that was the telephone lines in their cities. Thankfully for the residents, the problem was solved when the tower burned down on July 25, 1953.

A number of years ago, I requested my dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Lewis Spencer’s military records from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in Saint Louis, Missouri, only to be told that the records had been destroyed by a fire in 1973. I hadn’t heard about this before, and so really knew nothing about the details, except that I would never be able to find any more records of my dad’s military service during World War II, other than the ones we had, which was comparatively little. I wondered how it could be that the only military records for all those men were stored in one building, with no back up records. I know computers were not used as often, but there were things like microfiche back then. Nevertheless, the records were lost…and the loss felt devastating to me.

A number of years ago, I requested my dad, Staff Sergeant Allen Lewis Spencer’s military records from the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) in Saint Louis, Missouri, only to be told that the records had been destroyed by a fire in 1973. I hadn’t heard about this before, and so really knew nothing about the details, except that I would never be able to find any more records of my dad’s military service during World War II, other than the ones we had, which was comparatively little. I wondered how it could be that the only military records for all those men were stored in one building, with no back up records. I know computers were not used as often, but there were things like microfiche back then. Nevertheless, the records were lost…and the loss felt devastating to me.

When I heard about the fire that destroyed my dad’s records, it all seemed like the distant past, but in reality, it was during my high school years. Then, it just seemed like a bad dream…a nightmare really. I couldn’t believe that there was no way to get copies of those records. My dad’s pictures, one of which was signed by the pilot of Dad’s B-17, on which Dad was a top turret gunner. Those pictures and the few records are all we have of his war years, and to this day, that makes me sad.

The fire broke out on July 13, 1973 and quickly engulfed the top floor of the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC). In less 15 minutes from the time the fire was reported, the first firefighters arrived at the sixth floor of the building, only to be forced to retreat as their masks began to melt on their faces. The fire was that hot!! There was just no way to successfully save the documents that were stored there. The fire burned out of control for more than 22 hours…even with 42 fire districts attempting to extinguish the flames. It was not until five days later that it was finally completely out. Besides the burning of records, the tremendous heat of the fire warped shelves while water damage caused some surviving documents to carry mold.

About 73% to 80% of the approximately 22 million individual Official Military Personnel Files stored in the building were destroyed. The records lost were those of former members of the U.S. Army, the Army Air Force, and the Air Force who served between 1912 and 1963. My dad joined the Army Air Force on March 19, 1943 and was discharged October 3, 1945. Many of the documents lost were from those years. They were gone, and there was no way to get them back. The National Personnel Records Center staff continues to work to preserve the damaged records that ere saved. There were about 6.5 million records recovered since the fire.

Every year, my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I spend a week around the Fourth of July hiking in the Black Hills. We have been coming to the Black Hills for about 30 years, and it never gets old. I suppose it might if all we did was the normal touristy things, but when you get back in the wilderness areas of the Black Hills, it really is a whole different world, and it’s ever changing, especially when there is a heavy fire year. Unfortunately, this year seems to have been a fire year, at least in the Wildlife Loop of Custer State Park. The fire started on December 11, 2017, and while the cause of the Legion Lake Fire officially remains under investigation, it is believed to have been a downed power line that sparked the blaze. The wildfire shut down Custer State Park

Every year, my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I spend a week around the Fourth of July hiking in the Black Hills. We have been coming to the Black Hills for about 30 years, and it never gets old. I suppose it might if all we did was the normal touristy things, but when you get back in the wilderness areas of the Black Hills, it really is a whole different world, and it’s ever changing, especially when there is a heavy fire year. Unfortunately, this year seems to have been a fire year, at least in the Wildlife Loop of Custer State Park. The fire started on December 11, 2017, and while the cause of the Legion Lake Fire officially remains under investigation, it is believed to have been a downed power line that sparked the blaze. The wildfire shut down Custer State Park  that Monday, and burned an estimated 54,000 acres. It was believed to have started about 7:30 that morning.

that Monday, and burned an estimated 54,000 acres. It was believed to have started about 7:30 that morning.

The winds didn’t help matters either, gusting to 50 miles per hour. The fire moved along the Centennial Trail toward Star Academy East Campus ad Badger Hole. By Monday afternoon the head of the fire had crossed Heddy Draw and spread to both sides of Barnes Canyon Road. the ponderosa pines in the area were burned to the crown. It was so strange to see the green tops of the trees above the burnt orange lower sections of the trees and the blackened trunks.

Most of the wildlife fared well. The 860 bison that call the park home were left unscathed, but three of the park’s beloved begging burros had to be euthanized after the blaze. That is probably the saddest part of this for me, because we love the burros. They are gentle enough to eat out of your hand, and the love the attention everyone gives them. A few more of the burros still face an unknown fate due to the burns they received. The smell of a campfire that burned too long hung in the dry western South Dakota air for a long time. While we couldn’t smell the scorched trees any more, the scars were still visible everywhere.

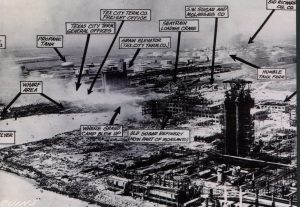

It was a typical day in Texas City, Texas…a port city in Galveston Bay. April was always warm, in the mid-70s, so it was perfect outdoor weather. Fires around the docks were a fairly common occurrence in Texas City, and it was not unusual for residents to travel down to the docks to watch the fires and the firemen working. Fires tend to attract the casual observer as well as the local news agencies. This day started out just as any other typical Texas day, but all that would change very soon. On the morning of April 16, 1947 a fire broke out on the S.S. Grandcamp. The fire produced a dense, brilliantly colored smoke that could be seen all over town. On board Grandcamp, among other things, was a supply of ammonium nitrate, which was producing the brilliant colors. The ship was docked in the Texas City port, so the smoke could be seen all over town. This fire, like any other, brought anybody who had any free time down to the dock to watch the action. This would be a fatal mistake for many of the bystanders.

It was a typical day in Texas City, Texas…a port city in Galveston Bay. April was always warm, in the mid-70s, so it was perfect outdoor weather. Fires around the docks were a fairly common occurrence in Texas City, and it was not unusual for residents to travel down to the docks to watch the fires and the firemen working. Fires tend to attract the casual observer as well as the local news agencies. This day started out just as any other typical Texas day, but all that would change very soon. On the morning of April 16, 1947 a fire broke out on the S.S. Grandcamp. The fire produced a dense, brilliantly colored smoke that could be seen all over town. On board Grandcamp, among other things, was a supply of ammonium nitrate, which was producing the brilliant colors. The ship was docked in the Texas City port, so the smoke could be seen all over town. This fire, like any other, brought anybody who had any free time down to the dock to watch the action. This would be a fatal mistake for many of the bystanders.

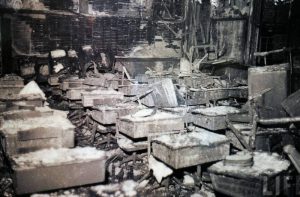

The ammonium nitrate on board the Grandcamp detonated at 9:12 am, blowing he ship apart and sending the cargo of peanuts, tobacco, twine, bunker oil and the remaining bags of ammonium nitrate 2,000 to 3,000 feet into the air. Fireballs streaked across the sky and could be seen for miles across Galveston Bay as molten ship fragments erupted out of the pier. The blast sent a fifteen foot tidal wave crashing onto the dock and flooding the surrounding area. Windows were shattered in Houston, 40 miles to the north, and people in Louisiana felt the shock 250 miles away. Most of the buildings closest to the blast were flattened, and there were many more that had doors and roofs blown off. The Monsanto plant which was only three hundred feet away, was destroyed by the blast. Most of the Texas City Terminal Railways’ warehouses along the docks were destroyed. Hundreds of employees, pedestrians and bystanders were killed. At the time of the Grandcamp’s explosion, only two additional vessels were docked in port…the S.S. High Flyer and the Wilson B. Keene, both American C-2 cargo ships similar to the Grandcamp.

The intensity of the blast sent shrapnel tearing into the surrounding area. Flaming debris ignited giant tanks full  of oil and chemicals stored at the refineries, causing a set of secondary fires and smaller explosions. The Longhorn II, a barge anchored in port, was lifted out of the water by the sheer force of the explosion and landed 100 feet away on the shore. Buildings blazed long after the initial explosion, provoking large scale emergency relief efforts throughout the day, that night, and into the following day. The fires in nearby industrial buildings and chemical plants spread the destruction even farther. The chief and 27 firefighters from the Texas City Fire Department were killed in the initial blast. Official estimates put the death toll at 567 and injuries at more than 5,000. Some of the dead were never identified, and some may never have been found at all.

of oil and chemicals stored at the refineries, causing a set of secondary fires and smaller explosions. The Longhorn II, a barge anchored in port, was lifted out of the water by the sheer force of the explosion and landed 100 feet away on the shore. Buildings blazed long after the initial explosion, provoking large scale emergency relief efforts throughout the day, that night, and into the following day. The fires in nearby industrial buildings and chemical plants spread the destruction even farther. The chief and 27 firefighters from the Texas City Fire Department were killed in the initial blast. Official estimates put the death toll at 567 and injuries at more than 5,000. Some of the dead were never identified, and some may never have been found at all.

The blast registered on a seismograph as far away as Denver, Colorado. Dockworker Pete Suderman remembers flying thirty feet as the blast carried him and several of the dock’s three-inch wooden planks across the pier. Nattie Morrow was in her home with her two children and sister-in-law Sadie. She watched the billowing smoke near the Monsanto plant from her back porch just prior to the blast. “Suddenly a thundering boom sounded, and seconds later the door ripped off its facing, skidded across the kitchen floor, and slammed down onto the table where I sat with the baby. The house toppled to one side and sat off its piers at a crazy angle. Broken glass filled the air, and we didn’t know what was happening.”

At the time of the explosion, phone services in Texas City were not working because of a telephone operators’ strike. When the operators learned of the accident, they quickly went back to work, but the strike caused an initial delay in coordinating rescue efforts. Once operators began calling for help, rescue workers from all over the area began responding immediately. The U.S. Army, Navy, Coast Guard, Marine Reserve and the Texas National Guard all sent personnel, including doctors, nurses and ambulances. The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston sent doctors, nurses, and medical students. Firefighters from Galveston, Houston, Fort Crockett, Ellington Field, and surrounding towns arrived to help. The cities of Galveston, Houston and San Antonio sent policemen to assist the Texas City Police Department in maintaining order after the explosion. The U.S. Army flew in blood  plasma, gas masks, food, and other supplies, provided bull-dozers to begin clearing the wreckage, and set up temporary housing for the survivors at Camp Wallace in Hitchcock. The Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America sent a flood of volunteers who provided first aid, food, water and comfort to city residents. Volunteers from other local organizations, and others who were not part of any organization, felt compelled to help. There was no operational hospital in Texas City at the time of the disaster, so volunteers converted city hall and chamber of commerce buildings into makeshift infirmaries. Many wounded were evacuated to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, the hospital at Fort Crockett, and hospitals in Houston.

plasma, gas masks, food, and other supplies, provided bull-dozers to begin clearing the wreckage, and set up temporary housing for the survivors at Camp Wallace in Hitchcock. The Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Boy and Girl Scouts of America sent a flood of volunteers who provided first aid, food, water and comfort to city residents. Volunteers from other local organizations, and others who were not part of any organization, felt compelled to help. There was no operational hospital in Texas City at the time of the disaster, so volunteers converted city hall and chamber of commerce buildings into makeshift infirmaries. Many wounded were evacuated to John Sealy Hospital in Galveston, the hospital at Fort Crockett, and hospitals in Houston.

During the Vietnam War, as in any war, children can become displaced because of the loss of their parents. The country has already lost so many people, and often there is no one to take these little orphans, so they often end up in an orphanage, waiting for someone to come along and adopt them. Many times, they live their entire childhood in that orphanage. For a country that has already be devastated by war, the cost of raising these children is detrimental. Such was the case for orphaned children from the Vietnam War. Then the United States made the decision to airlift these children to the United States to be adopted by American families who were waiting for children. The plan was dubbed Operation Baby Lift, and while it would end up being successful, it got of the a sad and rocky start on April 4, 1975, when the first plane crashed shortly after taking off from Tan Son Nhut airbase in Saigon. On board were more than 300 passengers. Of those, 138 passengers, mostly children were killed.

During the Vietnam War, as in any war, children can become displaced because of the loss of their parents. The country has already lost so many people, and often there is no one to take these little orphans, so they often end up in an orphanage, waiting for someone to come along and adopt them. Many times, they live their entire childhood in that orphanage. For a country that has already be devastated by war, the cost of raising these children is detrimental. Such was the case for orphaned children from the Vietnam War. Then the United States made the decision to airlift these children to the United States to be adopted by American families who were waiting for children. The plan was dubbed Operation Baby Lift, and while it would end up being successful, it got of the a sad and rocky start on April 4, 1975, when the first plane crashed shortly after taking off from Tan Son Nhut airbase in Saigon. On board were more than 300 passengers. Of those, 138 passengers, mostly children were killed.

Captain Dennis “Bud” Traynor was the captain on the plane. Many of the 138 passengers were children, and  many of them were under age 2 and so small, they had to be carried onto the plane. “We bucket-brigade-loaded the children right up the stairs into the airplane,” Traynor remembers. The flight began normally, but shortly into the flight, when the plane’s cargo doors malfunctioned they blew out, taking with them a chunk of the tail. There was a rapid decompression inside the aircraft, causing the pilot, Traynor, to crash land the C-5 cargo plane into a nearby rice paddy. Traynor managed to stabilize the plane and turn it back toward Vietnam. After that, his only option was a crash landing. The impact was fierce. “It cut all control cables to the tail,” explains Traynor. “So I’m pulling and pulling and pulling, and my nose is going down further and further and we’re going faster and faster and faster, and I can’t figure this out. We came to a stop and I thought to myself ‘I’m alive,'” he says. “And so I undid my lap belt, fell to the ceiling, rolled open the side window, and stepped out and saw the wings burning. And I thought, ‘Oh no, that’s the rest of the airplane.'” Out of the more than 300 people on board, the death toll included 78 children and about 50 adults, including Air Force personnel. More than 170 survived.

many of them were under age 2 and so small, they had to be carried onto the plane. “We bucket-brigade-loaded the children right up the stairs into the airplane,” Traynor remembers. The flight began normally, but shortly into the flight, when the plane’s cargo doors malfunctioned they blew out, taking with them a chunk of the tail. There was a rapid decompression inside the aircraft, causing the pilot, Traynor, to crash land the C-5 cargo plane into a nearby rice paddy. Traynor managed to stabilize the plane and turn it back toward Vietnam. After that, his only option was a crash landing. The impact was fierce. “It cut all control cables to the tail,” explains Traynor. “So I’m pulling and pulling and pulling, and my nose is going down further and further and we’re going faster and faster and faster, and I can’t figure this out. We came to a stop and I thought to myself ‘I’m alive,'” he says. “And so I undid my lap belt, fell to the ceiling, rolled open the side window, and stepped out and saw the wings burning. And I thought, ‘Oh no, that’s the rest of the airplane.'” Out of the more than 300 people on board, the death toll included 78 children and about 50 adults, including Air Force personnel. More than 170 survived.

While it was an unusual plan, hatched in the midst of the political fallout, the United States government announced the plan to get thousands of displaced Vietnamese children out of the country. President Ford directed that money from a special foreign aid children’s fund be made available to fly 2,000 South Vietnamese orphans to the United States. Operation Baby Lift lasted for just ten days. Baby Lift was carried out during the final, desperate phase of the war, as North Vietnamese forces closed in on Saigon. Although this first flight ended in tragedy, the rest of the flights were completed safely, and Baby Lift aircraft brought orphans across the Pacific until the mission’s conclusion on April 14, just 16 days before the fall of Saigon and the end of the war.

While it was an unusual plan, hatched in the midst of the political fallout, the United States government announced the plan to get thousands of displaced Vietnamese children out of the country. President Ford directed that money from a special foreign aid children’s fund be made available to fly 2,000 South Vietnamese orphans to the United States. Operation Baby Lift lasted for just ten days. Baby Lift was carried out during the final, desperate phase of the war, as North Vietnamese forces closed in on Saigon. Although this first flight ended in tragedy, the rest of the flights were completed safely, and Baby Lift aircraft brought orphans across the Pacific until the mission’s conclusion on April 14, just 16 days before the fall of Saigon and the end of the war.

Prior to December 1, 1958, fire drills were not normal procedure, and in fact, were not held at all. No one knew how important fire drills were, even though they knew the dangers of fire, and just how deadly it was. Mainly, they did not realize just how important fire drills were to the safe evacuation of people from a burning building. Prior to that day, when there was a fire, those who knew about the fire ran, and most didn’t think about raising the alarm to let others know. This was especially true in schools, where in reality, fire drills were exponentially more important, because the drill made an emergency seem like just another drill, and could be carried out, before the smell of smoke even arrived in the rooms of the school. Prior to December 1, 1958, the schools had an alarm, but all too often, setting it off was the last thing on the minds of the people in charge…mostly due to their own panic. Later it would be determined that with practice, an emergency situation could be handled, and the people evacuated quickly, if the procedure was simply a practiced maneuver that everyone knew and automatically executed.

Prior to December 1, 1958, fire drills were not normal procedure, and in fact, were not held at all. No one knew how important fire drills were, even though they knew the dangers of fire, and just how deadly it was. Mainly, they did not realize just how important fire drills were to the safe evacuation of people from a burning building. Prior to that day, when there was a fire, those who knew about the fire ran, and most didn’t think about raising the alarm to let others know. This was especially true in schools, where in reality, fire drills were exponentially more important, because the drill made an emergency seem like just another drill, and could be carried out, before the smell of smoke even arrived in the rooms of the school. Prior to December 1, 1958, the schools had an alarm, but all too often, setting it off was the last thing on the minds of the people in charge…mostly due to their own panic. Later it would be determined that with practice, an emergency situation could be handled, and the people evacuated quickly, if the procedure was simply a practiced maneuver that everyone knew and automatically executed.

So, what led up to the fire drill revelation? Basically, it was due to a fire at a grade school in Chicago that killed 90 students on this day in 1958. Our Lady of Angels School was operated by the Sisters of Charity in Chicago. In 1958, there were well over 1,200 students enrolled at the school, which occupied a large, old building. In  those days, little was done in the way of fire prevention. The building did not have any sprinklers and no regular preparatory drills were conducted. Those two factors combined, led to disaster when a small fire broke out in a pile of trash in the basement, and quickly burned out of control.

those days, little was done in the way of fire prevention. The building did not have any sprinklers and no regular preparatory drills were conducted. Those two factors combined, led to disaster when a small fire broke out in a pile of trash in the basement, and quickly burned out of control.

It is thought that the fire began about 2:30 pm. Within minutes, several teachers on the first floor smelled it. These teachers led their classes outside, but because it was never practiced, no one thought to sound a general alarm. The school’s janitor discovered the fire at 2:42 pm, and shouted for the alarm to be rung…but by then, at least ten precious minutes had passed since the fire started. Time to evacuate was quickly running out. Unfortunately, the janitor was either not heard or the alarm system did not operate properly. The students in the classrooms on the second floor were completely unaware of the rapidly spreading flames beneath them. It took a few more minutes for the fire to reach the second floor. By this time, panic had overtaken the students and teachers. Some panic stricken students jumped out windows to escape. I can only imagine the horror the firefighters must have felt as the roll up to the scene to find students hanging from the second floor windows, as they ran to try to catch them as they fell. Although the firefighters who were arriving on the scene tried to  catch them, some were injured. Firefighters also tried to get ladders up to the windows. One quick-thinking nun had her students crawl under the smoke and roll down the stairs, where they were rescued. Other classes remained in their rooms, praying for help. There was no protocol…no routine…and for 90 students and 3 nuns, no chance of survival. Several hours later, when the fire was finally extinguished, the authorities found the 90 students and 3 nuns in the ashes of the classrooms. Sadly, it is the horrific “lessons” that trigger the quickest move to change, and this fire was no different. These days, when students hear the alarm…which is automatic when smoke is detected, they line up, and leave the school in a calm and orderly manner. Fire drills save lives.

catch them, some were injured. Firefighters also tried to get ladders up to the windows. One quick-thinking nun had her students crawl under the smoke and roll down the stairs, where they were rescued. Other classes remained in their rooms, praying for help. There was no protocol…no routine…and for 90 students and 3 nuns, no chance of survival. Several hours later, when the fire was finally extinguished, the authorities found the 90 students and 3 nuns in the ashes of the classrooms. Sadly, it is the horrific “lessons” that trigger the quickest move to change, and this fire was no different. These days, when students hear the alarm…which is automatic when smoke is detected, they line up, and leave the school in a calm and orderly manner. Fire drills save lives.

Arthur Duperrault dreamed of sailing the high seas. He was a World War II veteran from Green Bay, Wisconsin and he wanted to give his family a sailing adventure. The winter of 1960 was rough, but now the winter of 1961, would be one of sunlight and warmth. Arthur, Jean, Brian, Terry Jo, and Renee, were heading for the Bahamas to soak up some sun. Arthur and his family headed to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where their boat, Bluebelle was waiting for them. It was a sixty foot two-masted sailboat.

Arthur Duperrault dreamed of sailing the high seas. He was a World War II veteran from Green Bay, Wisconsin and he wanted to give his family a sailing adventure. The winter of 1960 was rough, but now the winter of 1961, would be one of sunlight and warmth. Arthur, Jean, Brian, Terry Jo, and Renee, were heading for the Bahamas to soak up some sun. Arthur and his family headed to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where their boat, Bluebelle was waiting for them. It was a sixty foot two-masted sailboat.

With no real sailing experience, Arthur hired a man named Julian Harvey, who was a decorated Air Force bomber pilot who had served in World War II and the Korean War, to captain for him. Harvey brought along his wife of four months, Mary Dene. On Wednesday, November 8, 1961, Arthur, Julian, and their respective families began their journey. Soon, the occupants of Bluebelle would be in the Bahamas. First, Harvey steered Bluebelle toward Bimini, a miniature island chain. Then headed east, to Sandy Point, a village located on the southwest point of the Great Abaco Island. Here, the vacationers filled their days with snorkeling and picking up shells on the beautiful beaches.

On Sunday, November 12, 1961, Arthur and Julian went to the office of Roderick Pinder, who was Sandy Point’s commissioner, to fill out the forms that they needed to properly leave the Bahamas. Arthur told Roderick. “We’ll be back before Christmas.” Little did Arthur, his wife, or three children know, they would not be coming back for Christmas. Sunday would be Arthur’s last night alive. It would also be last night alive for Jean, Brian, Renee, and Julian Harvey’s wife, Mary Dene. Sunday dinner was cooked by Mary Dene, who made a chicken cacciatore and salad for the two families. At 9:00 pm that night, Terry Jo went to bed. Her room was in a small cabin in the back of the boat. Usually, Renee, her young sister, slept there too, but tonight, she was with her mom, dad, and brother in the cockpit. In the middle of the night, Terry Jo heard her brother scream, “Help, daddy, help!” The screams were followed by running and stamping noises. Terry Jo was terrified. After the running, the stamping, and the screams stopped, there was an eerie silence.

Terry Jo was terrified, but found the courage to leave her cabin. The main cabin, a kitchen and dining room during the day, transformed into a bedroom at night. There she saw her mom and big brother, in a pool of blood…dead. Cautiously, she went to check the other areas of the boat. Near the cockpit, she saw more blood and a knife. She made her way to the front of the boat. As Terry Jo was viewing the horror in front of her, somebody lunged at her. It wasn’t a stranger…it was the captain, Julian Harvey. “Get back down there!” he  screamed. With her heart pounding, Terry Jo went back to her cabin. She crawled into her bunk. Soon, water coming into the cabin told her that Bluebelle was sinking. She was too afraid to move. However, Harvey was moving all over the place. Soon, she saw Harvey in the doorway holding her big brother’s rifle. Then Harvey turned and walked out of the cabin, and she heard him climb the stairs back to the upper deck.

screamed. With her heart pounding, Terry Jo went back to her cabin. She crawled into her bunk. Soon, water coming into the cabin told her that Bluebelle was sinking. She was too afraid to move. However, Harvey was moving all over the place. Soon, she saw Harvey in the doorway holding her big brother’s rifle. Then Harvey turned and walked out of the cabin, and she heard him climb the stairs back to the upper deck.

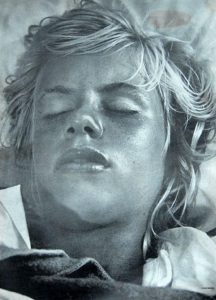

With water reaching the top of her mattress, Terry Jo knew she had to get out. Wading through the water, she climbed to the deck again. On deck she saw that the ship’s dinghy and rubber life raft were floating beside the boat. “Is the ship sinking?” she called out. “Yes!” Harvey shouted, coming up from behind her. He pushed the line to the dinghy into her hands. “Hold this!” he shouted. Numb from shock, Terry Jo let the line slip through her fingers. The dinghy slowly drifted away from the sinking Bluebelle. Harvey jumped overboard to catch it, and Terry Jo watched him swim after the dinghy and disappear into the night. She remembered the cork life float that was kept lashed to the top right side of the main cabin, which was now just barely above-water. She scrambled to the small, oblong float and quickly untied it. Just as the float came free, the boat deck sank beneath her feet. She pushed the float into the open water, and climbed onto the float. One of its lines snagged on the sinking ship. For a moment, she and the float were pulled underwater as the Bluebelle went down. Then the line came free, and they popped back to the surface. She huddled low on the float, afraid that the captain might be coming back. She had no water, no food, and nothing to protect her from the cold. The night was so dark that she couldn’t see anything.

For three days Terry Jo was battered by the salt water, and scorched by the sun…her only companions, a pod of porpoises. She had no food or water. Each day brought her closer to death. On Tuesday, a small red plane circled overhead. She waved at it for a long time with her blouse. The plane passed directly over her, but at an angle that made it impossible for the pilots to see her. When the sun rose on Thursday, she did not feel its burning rays. She was in a deep sleep close to death. Only the faintest spark of life was left. About midmorning she emerged from her stupor and opened her eyes. A huge shadow loomed above her like a great beast. Its rumble was so deep that she could feel its pounding rhythm in her chest. It seemed like a dream, until she looked up to the top of that great wall, and saw heads and waving arms. She could hear voices shouting. Finally, she felt herself lifted from the water. She passed out again. Terry Jo spent 11 days in a Miami hospital but had no permanent injuries

The day after the Bluebelle went down, an oil tanker spotted Harvey. When the captain pulled the tanker closer, he yelled, “My name is Julian Harvey. I am master of the Bluebelle.” In the days that followed, Harvey told the Coast Guard in Miami that he was the sole survivor of a grave accident. In the middle of the previous night, he said that a sudden squall damaged the sailboat. His wife, Mary Dene, and the Duperraults were injured when the masts and rigging collapsed. Gas lines in the engine room ruptured, and the ship caught fire as it sank. Harvey said he had managed to get in the dinghy, but tangled rigging trapped everyone else on board. A few days later, staying at the Sandman Hotel, Harvey heard that Terry Jo had survived. The next day, a maid at the hotel found Harvey’s bloody, lifeless body on the floor. He had killed himself.

A week after her rescue, officials questioned Terry Jo in her hospital bed. Her story, disproved Harvey’s account. Her father, mother, brother, and younger sister, along with Mary Dene Harvey, had been slaughtered aboard the Bluebelle, at the hands of Julian Harvey. The police suspect that Harvey killed his wife to collect money from her life insurance, and one theory suggests that Duperrault caught Harvey in the act, prompting the other murders. Terry Jo returned to Green Bay to live with her father’s sister and three cousins. When she was 12, she changed her name to Tere. Nearly 50 years later, in 2010, Tere finally revealed the details of the night her family was killed and her days spent drifting in open water in her book, Alone: Orphaned on the Ocean.