authors

They say that genius can be the closest thing to crazy, but I don’t really know how true that is. Sometimes I think that when a person is a genius, people drive them crazy. It’s the novelty of the thing, I suppose. People find out that the genius has a super high IQ, and they all seem to want something from them. Many people don’t really care about the genius as a person, just about how they might be able to make money off of them somehow. Not every inventor is a genius, but some of them are, as are some mathematicians, doctors, teachers, writers, and many other people too.

They say that genius can be the closest thing to crazy, but I don’t really know how true that is. Sometimes I think that when a person is a genius, people drive them crazy. It’s the novelty of the thing, I suppose. People find out that the genius has a super high IQ, and they all seem to want something from them. Many people don’t really care about the genius as a person, just about how they might be able to make money off of them somehow. Not every inventor is a genius, but some of them are, as are some mathematicians, doctors, teachers, writers, and many other people too.

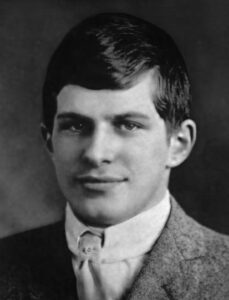

Sometimes the demands placed on these geniuses gets to be so heavy, that they might just snap. I don’t mean that they might go insane, although some of them have. The thing that seems to happen most, however, is that they might just decide to disappear. Several geniuses have simply vanished,  including William Sidis (who graduated from Harvard at 16, only to go into hiding, going from city to city and job to job), JD Salinger (author of Catcher in the Rye, who left Manhattan in 1953 to live on a “90-acre compound” in Cornish, NH. He remained there until his death in 2010, at age 91, saying he loved to write, but publishing was a terrible invasion of his privacy), Ettore Majorana (a theoretical physicist was considered one of the most deeply brilliant men in the world by Enrico Fermi, creator of the first nuclear reactor. One day he drained his bank account and simply vanished), David Thorne (an architect received so much attention for his work on jazz giant Dave Brubeck’s house in 1954, that he changed his professional name in the ‘60s to Beverly Thorne, got an unlisted phone number, and didn’t “resurface” until the 1980s), and Nick Gill (who at 21, was the youngest-ever British chef to win a Michelin star. He seemed destined for a life of fame and fortune and was hailed as a culinary genius. One day he told his brother he was going to disappear, and to “please, not look for him,” never to be seen again).

including William Sidis (who graduated from Harvard at 16, only to go into hiding, going from city to city and job to job), JD Salinger (author of Catcher in the Rye, who left Manhattan in 1953 to live on a “90-acre compound” in Cornish, NH. He remained there until his death in 2010, at age 91, saying he loved to write, but publishing was a terrible invasion of his privacy), Ettore Majorana (a theoretical physicist was considered one of the most deeply brilliant men in the world by Enrico Fermi, creator of the first nuclear reactor. One day he drained his bank account and simply vanished), David Thorne (an architect received so much attention for his work on jazz giant Dave Brubeck’s house in 1954, that he changed his professional name in the ‘60s to Beverly Thorne, got an unlisted phone number, and didn’t “resurface” until the 1980s), and Nick Gill (who at 21, was the youngest-ever British chef to win a Michelin star. He seemed destined for a life of fame and fortune and was hailed as a culinary genius. One day he told his brother he was going to disappear, and to “please, not look for him,” never to be seen again).

It isn’t known, as to why these geniuses would decide that they no longer wanted to be a part of the world, nor

are they to only people to do this by any means. Nevertheless, they seem to have one thing in common, their genius skill or knowledge seemed to take over their whole life, and people wouldn’t leave them alone, but rather hounded them unmercifully. I think I can understand how that would be enough to make someone want to disappear, but most people don’t actually go so far as to take that step. It is a rather extreme step to take, and for all we know some of these might have been killed or committed suicide. The sad reality for these genius minds is that the fame and constant pressure of celebrity was too much for them, and they just checked out, because the burden of knowledge was just too much for them.

are they to only people to do this by any means. Nevertheless, they seem to have one thing in common, their genius skill or knowledge seemed to take over their whole life, and people wouldn’t leave them alone, but rather hounded them unmercifully. I think I can understand how that would be enough to make someone want to disappear, but most people don’t actually go so far as to take that step. It is a rather extreme step to take, and for all we know some of these might have been killed or committed suicide. The sad reality for these genius minds is that the fame and constant pressure of celebrity was too much for them, and they just checked out, because the burden of knowledge was just too much for them.

When times get tough, new ideas are needed to get people through them. The Great Depression put many people out of work. Times don’t get much tougher than that. The government decided to try something new. The project that was put forward was the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP). The idea was to fund written work and support writers during those dark days. The project was deigned to be in operation from July 27, 1935 to October 1939. It was part of the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal program.

When times get tough, new ideas are needed to get people through them. The Great Depression put many people out of work. Times don’t get much tougher than that. The government decided to try something new. The project that was put forward was the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP). The idea was to fund written work and support writers during those dark days. The project was deigned to be in operation from July 27, 1935 to October 1939. It was part of the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal program.

Of course, this was not really designed to allow people to explore the idea of becoming a writer, but rather to ease the plight of the unemployed writer, and anyone who could qualify as a writer such as a lawyer, a teacher, or a librarian. As the Roosevelt Administration ironed out the details of the New Deal, the administration and writers’ organizations and persons of liberal and academic persuasions felt that somehow, they could come up with more appropriate work situations for this group, the writers, other than blue collar jobs on construction projects. The final project was for one all the arts, which was called Federal One. As part of President Roosevelt’s Second New Deal, Federal One was divided into five specialties…writers, historical records, theater, music, and art. Each specialty was headed by professionals in that field.

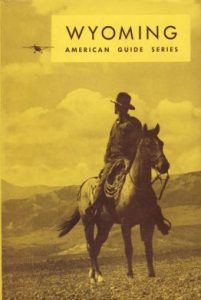

The Federal Writers Project was first operated under journalist and theatrical producer Henry Alsberg, and later John D Newsome, who were charged with employing writers, editors, historians, researchers, art critics, archaeologists, geologists and cartographers. Some 6,600 individuals were employed by the project compiling  local and cultural histories, oral histories, children’s books, and other works. The most well-known of these publications were the 48 state guides to America known as the American Guide Series. These books contained detailed histories of each state with descriptions of every city and town. They also contained a state’s history and culture, automobile tours of important attractions, and a portfolio of photographs. In each state a Writer’s Project staff was formed with editors and field workers. Some offices had as many as 150 people working, a majority of whom were women. Staff also included several well-known authors of the time and the program helped to launch the literary careers of others.

local and cultural histories, oral histories, children’s books, and other works. The most well-known of these publications were the 48 state guides to America known as the American Guide Series. These books contained detailed histories of each state with descriptions of every city and town. They also contained a state’s history and culture, automobile tours of important attractions, and a portfolio of photographs. In each state a Writer’s Project staff was formed with editors and field workers. Some offices had as many as 150 people working, a majority of whom were women. Staff also included several well-known authors of the time and the program helped to launch the literary careers of others.

Though the project produced useful work in the many oral histories collected from residents throughout the United States, it had its critics from the beginning, with many saying it was the federal government’s attempt to “democratize American culture.” Though most works were not political, some writers who supported political themes sometimes voiced their positions in their writings. This led some state legislatures to strongly oppose some projects and in a few states the American Guide Series books were printed only minimally. As the Project continued into the late thirties, criticism continued and several Congressmen just wanted to shut the project down. In October 1939, federal funding for the project ended, due to the Administration’s need for a larger defense budget. It was decided that the project could continue under state sponsorship, but even that ended in  1943. I’m sure that was due to World War II, and all that was needed to be poured into the war effort.

1943. I’m sure that was due to World War II, and all that was needed to be poured into the war effort.

While I am not really a fan of the government manufacturing jobs, I think that some of the great writings that came out of the Federal Writers Project, made this project one of the better government funded job ideas. During its existence, the project included a rich collection of rural and urban folklore, first-person narratives from people coping with the Depression, studies of social customs of various ethnic groups, and over 2,300 first person accounts of slavery. In documenting the common people, a number of books emerged from writers on the project including Jack Conroy’s The Disinherited and John Steinbeck’s classic The Grapes of Wrath. While this project was certainly unorthodox, it makes you wonder if we would have missed out of some great books, had it not been for this program. When the project ended, there were actually protests in an effort to keep it going, but it had run its course, and in 1943, it ended.

One of the best ways to form a dictatorship is to suppress knowledge. That’s one reason that propaganda is so important. When the people only hear what the government wants them to, they tend to become compliant…or at least that’s the theory. When Adolf Hitler was elected to office, he was the people’s choice, but they had no idea just how evil he was and how long they would be stuck with him. With the end of democracy, Germany became a one-party dictatorship. The Nazis began a massive propaganda campaign to win the loyalty and cooperation of Germans. The Nazi Propaganda Ministry, directed by Dr Joseph Goebbels, took control of all forms of communication in Germany…newspapers, magazines, books, public meetings, and rallies, art, music, movies, and radio. Viewpoints in any way threatening to Nazi beliefs or to the regime were censored or eliminated from all media. The German people were isolated from the outside world, and while they did not like it, the government became their only source of information.

One of the best ways to form a dictatorship is to suppress knowledge. That’s one reason that propaganda is so important. When the people only hear what the government wants them to, they tend to become compliant…or at least that’s the theory. When Adolf Hitler was elected to office, he was the people’s choice, but they had no idea just how evil he was and how long they would be stuck with him. With the end of democracy, Germany became a one-party dictatorship. The Nazis began a massive propaganda campaign to win the loyalty and cooperation of Germans. The Nazi Propaganda Ministry, directed by Dr Joseph Goebbels, took control of all forms of communication in Germany…newspapers, magazines, books, public meetings, and rallies, art, music, movies, and radio. Viewpoints in any way threatening to Nazi beliefs or to the regime were censored or eliminated from all media. The German people were isolated from the outside world, and while they did not like it, the government became their only source of information.

Germany was now led by a self-educated, high school drop-out named Adolf Hitler, who was by nature strongly anti-intellectual. For Hitler, the reawakening of the long-dormant Germanic spirit, with its racial and militaristic  qualities, was far more important than any traditional notions of learning. Books and writings by such authors as Henri Barbusse, Franz Boas, John Dos Passos, Albert Einstein, Lion Feuchtwanger, Friedrich Förster, Sigmund Freud, John Galsworthy, André Gide, Ernst Glaeser, Maxim Gorki, Werner Hegemann, Ernest Hemingway, Erich Kästner, Helen Keller, Alfred Kerr, Jack London, Emil Ludwig, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, Karl Marx, Hugo Preuss, Marcel Proust, Erich Maria Remarque, Walther Rathenau, Margaret Sanger, Arthur Schnitzler, Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, Jakob Wassermann, H.G. Wells, Theodor Wolff, Emilé Zola, Arnold Zweig, and Stefan Zweig, were suddenly unGerman. Their books were pulled from libraries and schools. Then, on the night of May 10, 1933, an event unseen in Europe since the Middle Ages occurred as German students from universities once regarded as among the finest in the world, gathered in Berlin to burn books with unGerman ideas. It was the Nazi burning of knowledge. Students can be very impressionable, and easily lead, and these students played right into Hitler’s hand.

qualities, was far more important than any traditional notions of learning. Books and writings by such authors as Henri Barbusse, Franz Boas, John Dos Passos, Albert Einstein, Lion Feuchtwanger, Friedrich Förster, Sigmund Freud, John Galsworthy, André Gide, Ernst Glaeser, Maxim Gorki, Werner Hegemann, Ernest Hemingway, Erich Kästner, Helen Keller, Alfred Kerr, Jack London, Emil Ludwig, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, Karl Marx, Hugo Preuss, Marcel Proust, Erich Maria Remarque, Walther Rathenau, Margaret Sanger, Arthur Schnitzler, Upton Sinclair, Kurt Tucholsky, Jakob Wassermann, H.G. Wells, Theodor Wolff, Emilé Zola, Arnold Zweig, and Stefan Zweig, were suddenly unGerman. Their books were pulled from libraries and schools. Then, on the night of May 10, 1933, an event unseen in Europe since the Middle Ages occurred as German students from universities once regarded as among the finest in the world, gathered in Berlin to burn books with unGerman ideas. It was the Nazi burning of knowledge. Students can be very impressionable, and easily lead, and these students played right into Hitler’s hand.

The youth-oriented Nazi movement had always attracted a sizable following among university students. Even back in the 1920s they thought Nazism was the wave of the future. They joined the National Socialist  German Students’ League, put on swastika armbands and harassed anti-Nazi teachers. Many formerly reluctant professors were swept along by the outpouring of student enthusiasm that followed Hitler’s seizure of power. Most of the professors eagerly surrendered their intellectual honesty and took the required Nazi oath of allegiance. They also wanted to curry favor with Nazi Party officials in order to grab one of the academic vacancies resulting from the mass expulsion of Jewish professors and deans. The entire education system of a nation changed…almost overnight. As the German-Jewish poet, Heinrich Heine, had declared, a hundred years before the advent of Hitler, “Wherever books are burned, human beings are destined to be burned too.” And so it was in the end.

German Students’ League, put on swastika armbands and harassed anti-Nazi teachers. Many formerly reluctant professors were swept along by the outpouring of student enthusiasm that followed Hitler’s seizure of power. Most of the professors eagerly surrendered their intellectual honesty and took the required Nazi oath of allegiance. They also wanted to curry favor with Nazi Party officials in order to grab one of the academic vacancies resulting from the mass expulsion of Jewish professors and deans. The entire education system of a nation changed…almost overnight. As the German-Jewish poet, Heinrich Heine, had declared, a hundred years before the advent of Hitler, “Wherever books are burned, human beings are destined to be burned too.” And so it was in the end.

I have been reading my Great Aunt Bertie Schumacher’s journal for a while now, and every time I pick it up I find something new. She started her journal by talking about how any writer can become famous in time, simply by observing the events around them and writing about those events, how they made people feel, and what happened because of those events. As a writer myself, I began to think about what she said, because there really is a vast difference, I think, between a writer and a reporter. A reporter simply tells the events as they happened, but a writer elaborates on the events, the people involved, and their feelings. There are reporters who are writers, obviously, but I think it would be very hard for a writer not to interject their thoughts and feelings into a report.

I have been reading my Great Aunt Bertie Schumacher’s journal for a while now, and every time I pick it up I find something new. She started her journal by talking about how any writer can become famous in time, simply by observing the events around them and writing about those events, how they made people feel, and what happened because of those events. As a writer myself, I began to think about what she said, because there really is a vast difference, I think, between a writer and a reporter. A reporter simply tells the events as they happened, but a writer elaborates on the events, the people involved, and their feelings. There are reporters who are writers, obviously, but I think it would be very hard for a writer not to interject their thoughts and feelings into a report.

Aunt Bertie wanted to tell a little bit about the things that were going on in their time. Still, she could not help but put into words how she felt about the events of the day. She mentioned that the first Kindergarten was formed in 1873. At that time there were only about 200 high schools in the entire country, but by 1900 there were 6000, along with colleges that were heavily endowed by the Rockefeller, Stanford, and Vanderbilt families. Fisk College for “blacks” came into being. Women were coming to the foreground. Football became a part of college life. You could become a doctor in four months…later it took three years, and we all know it takes much longer now. At that time, 98% of children were in the grades. Aunt Bertie mentions that it was thought that education was a cure all. Authors like Emily Dickinson, Bret Hart, and Mark Twain tried to enrich the world. There were streetcar and yacht races, P.T Barnum Circus, Dwight Moody held mass revivals, and McGuffy’s Reader taught moral lessons. And then she tells about the thing that bothers her the most, when she said, “But all this did not abolish CHILD LABOR!”  It seemed to Aunt Bertie that there were so many changes that the nation was seeing, but the one thing that appalled her the most at the time, was still there, and still endangering the lives of children. It was so hard for her to imagine that with everything else moving with such monumental steps toward a more modern civilization, that was so much more educated, that no one could stop child labor. In fact it seemed to her that no one noticed it, or even cared at all.

It seemed to Aunt Bertie that there were so many changes that the nation was seeing, but the one thing that appalled her the most at the time, was still there, and still endangering the lives of children. It was so hard for her to imagine that with everything else moving with such monumental steps toward a more modern civilization, that was so much more educated, that no one could stop child labor. In fact it seemed to her that no one noticed it, or even cared at all.

Her writings picture disasters, such as the panic in 1873, at the height of the reconstruction of the 1870’s…widespread unemployment, bankruptcy of many people, and failure of businesses, the Great Chicago fire and fires in Wisconsin, Boston, and other places that caused the failure of Insurance Companies who did not have enough Reserves to cover all of these disasters, railroad strikes and violence. Then she mentions what she terms “the sins of society”, one million people living in New York slums…ten to fifteen people in three rooms. The thought of so many people being forced to live in such appalling conditions tore at Aunt Bertie’s heart. Somehow, these things just should not be, and yet this was the world we were living in at that time.

Aunt Bertie wanted to tell about the things that were changing in our world, and how many improvements those changes were making to the world, but her tender heart just couldn’t get past the horrible injustices she could still see. There are lessons to be learned from her writings. Lessons of compassion, kindness, charity, and love for our fellow man. All too often we are so busy working on the improvements we want to make in our lives, society, and our  world in general, that we forget about how those things could affect the lives of others. The greed of the factory owners could not see past the profit to what their child laborers were suffering. Many changes have come from the horrors of the past. Child labor laws now protect our children, and as an insurance agent, I know that companies must hold enough in reserve to cover disastrous losses, and that while no insurance company is completely safe from failure, there is far less chance of it these days because of those reserves. While those days and events tore at Aunt Bertie’s tender heart, maybe society wasn’t totally deaf to the plight of the people after all.

world in general, that we forget about how those things could affect the lives of others. The greed of the factory owners could not see past the profit to what their child laborers were suffering. Many changes have come from the horrors of the past. Child labor laws now protect our children, and as an insurance agent, I know that companies must hold enough in reserve to cover disastrous losses, and that while no insurance company is completely safe from failure, there is far less chance of it these days because of those reserves. While those days and events tore at Aunt Bertie’s tender heart, maybe society wasn’t totally deaf to the plight of the people after all.