Wyoming

Ghost towns dot the landscape of the United States, including Hamilton City, Wyoming, which is also known as Miner’s Delight. The town is located in Fremont County, on the southeastern tip of the Wind River Range. Miner’s Delight was in a prosperous area during the mining boom in the American West in the second half of the 19th century. It was actually a “sister city” of Atlantic City and South Pass City, however they are more well known and have fared better that Miner’s Delight. Nevertheless, a few buildings still stand today as a reminder of an era in Wyoming’s past history.

Ghost towns dot the landscape of the United States, including Hamilton City, Wyoming, which is also known as Miner’s Delight. The town is located in Fremont County, on the southeastern tip of the Wind River Range. Miner’s Delight was in a prosperous area during the mining boom in the American West in the second half of the 19th century. It was actually a “sister city” of Atlantic City and South Pass City, however they are more well known and have fared better that Miner’s Delight. Nevertheless, a few buildings still stand today as a reminder of an era in Wyoming’s past history.

Like most western mining towns, Miner’s Delight went through several boom-bust periods. With the boom-bust periods came corresponding increases and declines in its population. In 1868, gold was in the area, and by 1870, at the height of the mine’s operations. At that point, the population in Hamilton City was 75, forty of whom were miners. The original boom of mining activity “busted” from 1872 to 1874. Then, by the 1880s a new era of economic prosperity had dawned. There were smaller booms in 1907 and in 1910, and even during the Great Depression. The town was inhabited as late as 1960. By 2015, there were no residents in the town.

Jonathan Pugh founded the Miners Delight mine, which was located about a quarter mile west of the town then known as Hamilton City. The normal boom and bust periods followed, eventually leading to the mine completely shutting down in March 1882. The mine was not used again until after the turn of the 20th century. Then, two brief boom periods in 1907 and in 1910, were in relation to mining operations.

There was one famous incident involving Miner’s Delight which occurred there in March 1893. The incident was widely covered in the press at the time, which was in Cheyenne and was read throughout Wyoming. It came to be known as “the brass lock service mystery.” The postmaster of Miner’s Delight, James “Jimmy” Kime had attempted to ship eight registered letters via the Rawlins and Northwestern’s line’s Lander-to-Rawlins stagecoach to the Postmaster in Rawlins using the “brass lock service.” The Post Office’s “brass lock service” utilized canvas pouches, which were locked with brass locks. The only persons that had a key were the Postmasters along the stage line. When Kime’s pouch reached its destination in Rawlins some 120 miles to the southeast, however, the postmaster there discovered that someone had cut the pouch and stolen all the registered letters. The crime was unheard of

The US Postal inspectors investigated the matter for many months. During that time, a number of other related thefts of various valuables on the line from the locked pouches occurred. Finally, they arrested Postmaster John Gatlin of the Myersville Station near today’s Jeffrey City, Wyoming, along with his wife Stella. The couple was tried in Laramie City and the trial into the Fall of 1893. At that point, charges against John Gatlin were dropped, after Stella Gatlin confessed to stealing the items, due to what she claimed to be her illness of kleptomania. Her affidavit stated that “she had struggled for years to overcome the mania, while keeping it a secret from her husband.” On November 25, 1893, the jury found Mrs. Gatlin guilty. Two days later, she was taken to the Laramie Prison, where she was registered as Prisoner #150, the first woman to be imprisoned there after being convicted of a federal crime in Wyoming. Following a period of “good conduct” she was released early in December 1894, and following her departure, prison officials added a special new wing exclusively for women, with individual cells and a toilet.

Today, the ghost town at Miner’s Delight which eventually went by its nickname, stands as a testament to the

passage of time and provides historians and tourists with a peek at early Wyoming life and the gold mining culture. There are still seventeen structures, including seven cabins, one saloon, one meat house, one shop or barn, one shaft house, one pantry, one cellar, three privies, and a corral on the property. All of the buildings are constructed of logs or unfinished lumber.

passage of time and provides historians and tourists with a peek at early Wyoming life and the gold mining culture. There are still seventeen structures, including seven cabins, one saloon, one meat house, one shop or barn, one shaft house, one pantry, one cellar, three privies, and a corral on the property. All of the buildings are constructed of logs or unfinished lumber.

When a dam is built, the purpose is to create a reservoir, thereby allowing for the accumulated water to be used to create irrigation for local farmers. In theory, that was the plan for the dam in Hot Springs County, Wyoming that would become known as Anchor Dam, and the resulting “reservoir” to be nicknamed “the reservoir that wouldn’t hold water” and occasionally, “boondoggle.” The dam is located 35 miles west of Thermopolis, Wyoming.

When a dam is built, the purpose is to create a reservoir, thereby allowing for the accumulated water to be used to create irrigation for local farmers. In theory, that was the plan for the dam in Hot Springs County, Wyoming that would become known as Anchor Dam, and the resulting “reservoir” to be nicknamed “the reservoir that wouldn’t hold water” and occasionally, “boondoggle.” The dam is located 35 miles west of Thermopolis, Wyoming.

The US Bureau of Reclamation built the dam in the 1950s. It was intended to provide a reliable supply of irrigation water, but after three years and $3.4 million spent on construction, it became clear that the geology of the area would not allow the reservoir to fill. After more than a decade of continuing attempts at remediation, the final cost of the dam topped $7 million, and its reservoir still holds very little water. The concrete thin-arch dam was completed in 1960 by the United States Bureau of Reclamation as a water storage project. The 208-foot-high dam structure impounds the water of the South Fork of Owl Creek, with the spillway designed as an unnecessary central overflow. Owl Creek rises in the Absaroka Mountains of northwestern Wyoming, and it was the site of early agriculture in the area. As homesteaders settled the region in the 1890s, it would become Hot Springs County. No area can support agriculture or livestock without water, so they knew something would have to be done. Ranchers used irrigation ditches to bring water from Owl Creek to pastures or to help grow livestock feed crops like alfalfa.

As construction began, the crews discovered “solution cavities” in the bedrock forced the re-positioning and re-configuration of the dam, causing delays and added expense. Solution caves or cavities are formed by the dissolution of rock along and adjacent to joints, fractures, and faults. These cavities are created by water passing through soluble rocks, leading to underground cavities and cave systems. The same karst solution cavities prevented Anchor Reservoir from filling its design capacity of 17,400 acre-feet. The reservoir has never been full. Since the dam was constructed, more than 50 sinkholes had been identified in the underlying Chugwater Formation geology of the reservoir basin. Some of the sinkholes were 30 feet in diameter and 35 feet deep. The site’s lack of “hydraulic integrity” was well known to Bureau scientists before and during construction, which begs the question…why was this project ever approved?

Bureau of Reclamation policies mandated that the Owl Creek farmers must organize an irrigation district, which would oversee distributing water to members and collecting payment. This was not well received, and a number of farmers in the area did not want to join, for two reasons. First, not everyone thought they needed the extra water, and they thought that their business would suffer if had recurring repayment costs for the project. Under Wyoming’s “first-in-time-first-in-rights” system of water law, farmers and ranchers with water rights filed earlier in time are allowed to take all the water they are entitled to before their neighbors with later rights get any. On Owl Creek, the farmers and ranchers who joined later and therefore had lower priority water rights tended to favor the proposed reservoir.

The Bureau of Reclamation rule that farmers getting project water could not own more than 160 acres, or 320 if married, was a source of contention, however. This rule was designed with the small family farm on fertile soil in mind. In the high altitude, short season, arid Owl Creek Mountains, 320 acres was nowhere near enough for cattle ranching, meaning that the rancher would not contribute. Efforts by local dam proponents to force reluctant ranchers to join the irrigation district prompted a series of lawsuits that held up progress on Anchor Dam until 1954. In 1954, Wyoming’s US senator, Frank Barrett, succeeded in having Anchor Dam exempted

from the acreage limit. Immediately, a group of ranchers changed their minds and joined the irrigation district. With that, the Bureau of Reclamation began seriously planning for construction. Nevertheless, it was all for not, because in the end, the reservoir only filled enough to provide some irrigation benefit through July and August of each season, as it still is today. The Anchor dam is still operated by the local Owl Creek Irrigation District.

from the acreage limit. Immediately, a group of ranchers changed their minds and joined the irrigation district. With that, the Bureau of Reclamation began seriously planning for construction. Nevertheless, it was all for not, because in the end, the reservoir only filled enough to provide some irrigation benefit through July and August of each season, as it still is today. The Anchor dam is still operated by the local Owl Creek Irrigation District.

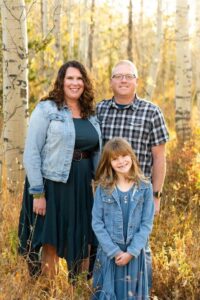

My grandniece, Manuela Ortiz is a super sweet girl, who married into our family when she married my grandnephew, James Renville. They are so perfect for each other, because they are opposites who complement each other so well. Manuela is very outgoing, and she has opened up some new vistas for James. He has always loved to travel, and since Manuela immigrated from Columbia, they now have family in two countries. They went down to Columbia last year, and plan to go again in June. James loves her family, and they love him. Manuela has shown him all the sights of her home country, and they had a wonderful time. They are excited to be going again.

My grandniece, Manuela Ortiz is a super sweet girl, who married into our family when she married my grandnephew, James Renville. They are so perfect for each other, because they are opposites who complement each other so well. Manuela is very outgoing, and she has opened up some new vistas for James. He has always loved to travel, and since Manuela immigrated from Columbia, they now have family in two countries. They went down to Columbia last year, and plan to go again in June. James loves her family, and they love him. Manuela has shown him all the sights of her home country, and they had a wonderful time. They are excited to be going again.

Last year, Manuela was given a promotion to Counseling Manager at the Wyoming Housing Network. She came

to this country on a work visa to learn English, which she planned to use to improve her work status in Columbia, but things just worked out for the better here, because her language skills were very much valued at her new place of employment. They realized that she was going to be a great asset to the company, and they wanted to make sure she was happy. They succeeded!! Manuela has been making her department a better place for the counseling of first-time home buyers, and they are very happy with her work. She is a great manager and an easy person to work with.

to this country on a work visa to learn English, which she planned to use to improve her work status in Columbia, but things just worked out for the better here, because her language skills were very much valued at her new place of employment. They realized that she was going to be a great asset to the company, and they wanted to make sure she was happy. They succeeded!! Manuela has been making her department a better place for the counseling of first-time home buyers, and they are very happy with her work. She is a great manager and an easy person to work with.

Manuela and James also became first-time home buyers, when they had the opportunity to buy James’ childhood home from his mom. They did quite a bit of updating on the home before they moved in and have plans for more updates over the coming year. They are going to be replacing some of the old flooring, and they plan to hire a landscaping team to come in and do some work on the back yard. The house was a great house

before, but I’m sure it is even more beautiful now, and since she is a first-time housing counselor, they already knew what to expect as first-time buyers.

before, but I’m sure it is even more beautiful now, and since she is a first-time housing counselor, they already knew what to expect as first-time buyers.

While they are very settled these days, their love of travel is still very much intact. They are planning to take a little trip down to Saratoga, Wyoming to relax and enjoy the beautiful country there. They are very active, and the great outdoors is calling their names. I can relate. I love to hike and such too, so the idea of getting out in nature is very appealing. I know they will have a wonderful time, and I’m sure this will be just one of many future trips for them. Today is Manuela’s birthday. Happy birthday Manuela!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Douglas Arnold Preston was destined for great things in the state of Wyoming. Born on December 19, 1858, to Finney D Preston and Phoebe Mundy. He was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1878 and practiced law in Illinois courts until 1887. Then he decided to relocate to Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. During his life in Wyoming, Preston was not only an attorney, but also a politician. He served as the 6th Attorney General of Wyoming from 1911 to 1919, as a member of the Democratic Party. He also served as a member of the Wyoming House of Representatives from 1903 to 1905, and as a member of the Wyoming Senate in 1929 until his death.

Douglas Arnold Preston was destined for great things in the state of Wyoming. Born on December 19, 1858, to Finney D Preston and Phoebe Mundy. He was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1878 and practiced law in Illinois courts until 1887. Then he decided to relocate to Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory. During his life in Wyoming, Preston was not only an attorney, but also a politician. He served as the 6th Attorney General of Wyoming from 1911 to 1919, as a member of the Democratic Party. He also served as a member of the Wyoming House of Representatives from 1903 to 1905, and as a member of the Wyoming Senate in 1929 until his death.

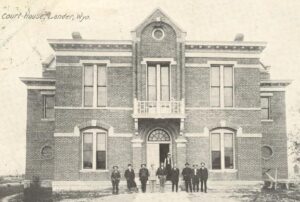

When Preston moved to Wyoming in 1887, he established a law office in Rawlins in partnership with John R Dixon. Apparently, Rawlins wasn’t his cup of tea, so the following year, he moved to Lander, where he continued his legal practice. In 1895, he again relocated, settling in Rock Springs, which became his long-term residence and base for his legal and political career.

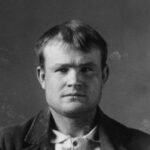

While Preston’s political career was extensive, probably one of the oddest parts of his legal career was the fact that he was once retained as a defense attorney for the infamous Butch Cassidy. Cassidy and his cohort, Al Hainer, had been arrested on April 11, 1892, a seven-man posse led by Uinta County Sheriff John Ward and Deputy Sheriff Bob Calverly, and charged in Fremont County with grand larceny “involving the theft of a horse valued at forty dollars from the Grey Bull Cattle Company on or about October 1, 1891.” District Court Judge Jesse Knight set bond at $400 each and both men were released pending trial. The trial was delayed for more than a year, due mostly to problems encountered in locating one prosecution witness and several defense witnesses. During that time, Cassidy retained Douglas A Preston of Lander as his attorney. Preston was assisted by C F Rathbone.

Preston and Cassidy had crossed paths and become friends so retaining him made sense. Unsubstantiated  rumor has it that Cassidy and Preston met when Cassidy saved Preston from a beating in a saloon in Rock Springs. However, that rumor has been disputed, and since Cassidy was an outlaw, it seems odd that he would play the hero in that one situation. Nevertheless, the two men were friends, and Preston did defend Cassidy.

rumor has it that Cassidy and Preston met when Cassidy saved Preston from a beating in a saloon in Rock Springs. However, that rumor has been disputed, and since Cassidy was an outlaw, it seems odd that he would play the hero in that one situation. Nevertheless, the two men were friends, and Preston did defend Cassidy.

The trial finally began in Lander on June 20, 1893, with Judge Knight presiding. The trial was short and the defense simple. Cassidy and Hainer did not deny being in possession of the horses but maintained they had bought them from a man named Billy Nutcher in good faith, unaware they were stolen. Conveniently, though he had been subpoenaed to testify, Nutcher did not appear at the trial. Nor did two men Cassidy claimed had witnessed the transaction. In the end, the jury deliberated only a few hours before finding both men not guilty. The reality was that there was just not enough evidence.

As the trial progressed and a “not guilty” verdict appeared likely, rancher Otto Franc filed charges against Cassidy and Haines in the theft of different horses in August of 1891, valued at $50. Both were re-arrested and were once again freed on bond. The trial on the new charge opened on June 30, 1894. While Cassidy was found guilty, Hainer was once again acquitted. On July 10, Judge Knight sentenced Cassidy to two years at hard labor in the Wyoming State Penitentiary in Laramie. That pretty much ended the relationship with Preston and Cassidy, and Preston went on to focus on his political career.

Preston served as the prosecuting attorney for Richland County, Illinois from 1880 to 1894. By 1889, and now in Wyoming since 1887, Preston was selected as one of the Democratic delegates to the Wyoming Constitutional Convention. Their task was to draft the state’s constitution for submission to the US government  for statehood. From 1903 to 1905, Preston served in the Wyoming House of Representatives. Governor Joseph M Carey appointed him as Attorney General of Wyoming in 1911, and he was reappointed by Governor John B Kendrick in 1915.

for statehood. From 1903 to 1905, Preston served in the Wyoming House of Representatives. Governor Joseph M Carey appointed him as Attorney General of Wyoming in 1911, and he was reappointed by Governor John B Kendrick in 1915.

Preston was elected to the Wyoming Senate in 1928, but on October 8, 1929, he was involved in a car crash that left him with four broken ribs and a severe skull fracture. Unable to recover from his injuries, Preston died on October 21, 1929, in a hospital in Rock Springs, Wyoming. He was 70 years old. In the 1930 Wyoming state elections, his widow, Anna Preston, was nominated as the Democratic candidate for Wyoming Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Traveling west in the mid 1800s was not an easy undertaking. It is often filled with hardship and heartache. Traveling westward in those days was not for the faint of heart or the weak in constitution. One family was heading out to Oregon, and things just didn’t go as planned. The Magill family consisted of Caleb and Mary Magill and their six children ranging from the eldest, Benjamin at 15 years, to the youngest, Ada at 3 years.

Traveling west in the mid 1800s was not an easy undertaking. It is often filled with hardship and heartache. Traveling westward in those days was not for the faint of heart or the weak in constitution. One family was heading out to Oregon, and things just didn’t go as planned. The Magill family consisted of Caleb and Mary Magill and their six children ranging from the eldest, Benjamin at 15 years, to the youngest, Ada at 3 years.

The trip from Brown County, Kansas to Oregon would be a long one, and it was often fraught with danger, so the family wanted to get an early start. One good thing was that their June 1864 early start put them ahead of some of the troubles that just weeks later lead to the deaths on the trail of Mary Kelly and Martin Ringo. Long-simmering tensions along the trails broke out into sporadic warfare later that summer between emigrants and people of the Lakota Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribes. Kelly and Ringo were victims of those tensions.

Unfortunately, missing out on those tensions didn’t make the trip easier for the Magill family. Late in June 1864, 3-year-old, Ada Magill fell ill with dysentery when they were camped near Fort Laramie. They stayed in camp until Ada’s health improved, and then the family continued along the trail another 100 miles to a spot near present Glenrock, Wyoming, in Converse County. In early July 1864, the family was camped alongside Deer Creek, near present Glenrock, when Ada again became sick, but next morning seemed better, so the family continued on. They had gone only a few miles when Ada became very ill again, so they stopped and camped. That night, July 3, she died, as Caleb told the story years later. Devastated, but under the gun to get to Oregon before winter, they built a coffin for little Ada from the boards of an abandoned wagon. They buried Ada in her  “Sunday best calico dress,” as the family remembered it later, then, “They heaped stones on the grave to keep wolves and coyotes out and went on toward Oregon,” according to historian and retired schoolteacher Randy Brown.

“Sunday best calico dress,” as the family remembered it later, then, “They heaped stones on the grave to keep wolves and coyotes out and went on toward Oregon,” according to historian and retired schoolteacher Randy Brown.

The Magill family went on to Oregon and settled in Polk County south of Portland in the Willamette Valley. I’m sure the arrival was bittersweet, because they were still grieving. Brown said that most of the information he got on the Magill family came from W W Morrison of Cheyenne, who was a freight conductor on the Union Pacific in the 1940s. Strangely, when Morrison contacted Magill family members still living at that time in Oregon, little information was available on Ada or her passing, and no family letters or diaries mentioning that have survived, so far as is known. The grave is not mentioned in any other emigrant diaries that have turned up. Nevertheless, its location is well documented.

The Oregon Trail route continued be an important trail long after the end of the covered wagon era. A new railroad was built in 1888, that passed close to Ada’s grave but respectfully, did not disturb it. Engineers were surveying for a better road between Glenrock and Casper in 1912, and they found the Magill grave, on a knoll 20 feet north of the old trail and marked with a rough, inscribed headstone. They knew it would end up right in the centerline of the new road. Surveyor L C Bishop, who later would become Wyoming’s state engineer, or chief water officer, decided to move the grave 30 feet north to the edge of the new road. As they dug up the grave, they found under a large stone slab about five feet down, according to Brown, Bishop, and a shovel crew of convicts from the Converse County jail “pieces of the little girl’s skull, a few small bones, some pearl buttons  and a few cut nails.” It had to be a really hard find, but that is what happened to those old pine box graves in those days. I’m sure they felt awful. Bishop carved a new stone with the same inscription as the original and buried the original about three feet deep in the new grave. I feel like that was a very respectful and honorable thing to do.

and a few cut nails.” It had to be a really hard find, but that is what happened to those old pine box graves in those days. I’m sure they felt awful. Bishop carved a new stone with the same inscription as the original and buried the original about three feet deep in the new grave. I feel like that was a very respectful and honorable thing to do.

While the railroad is no longer used and was removed in the 1980s, Ada Magill’s grave still remains, protected by a sturdy fence, and marked with a plaque placed by the Oregon-California Trails Association. The Ada Magill’s grave lies in sight of the North Platte River.

In the United States, at least on American soil, World War II seemed so far away, but the reality is that in parts of the United States, including Wyoming, the war, or part of it was closer to home than we realized. In fact, it was as close as an hour away from where my mom’s family lived, in Casper, Wyoming. Of course, I don’t mean the fighting, but the area was still connected to World War II. In Douglas, Wyoming, there was an internment camp for Prisoners of War (POW) called Camp Douglas. The camp was used between January 1943 and February 1946 housing first Italian and then German prisoners of war in the United States. During 1942, the first year of United States involvement in World War II, an estimated 2000 prisoners came to the United States. The POW camps overseas were so overcrowded that by September they needed a place to take them, where they could safely be contained. In order to be prepared for the 50,000 POWs being held by the British in North Africa, the US needed to reactivate the Civilian Conservation Corps camps. They opened unused portions of several major military bases; utilizing such facilities as fairgrounds, racetracks, armories, and auditoriums; and setting up “tent cities” in remote areas of the country.

In the United States, at least on American soil, World War II seemed so far away, but the reality is that in parts of the United States, including Wyoming, the war, or part of it was closer to home than we realized. In fact, it was as close as an hour away from where my mom’s family lived, in Casper, Wyoming. Of course, I don’t mean the fighting, but the area was still connected to World War II. In Douglas, Wyoming, there was an internment camp for Prisoners of War (POW) called Camp Douglas. The camp was used between January 1943 and February 1946 housing first Italian and then German prisoners of war in the United States. During 1942, the first year of United States involvement in World War II, an estimated 2000 prisoners came to the United States. The POW camps overseas were so overcrowded that by September they needed a place to take them, where they could safely be contained. In order to be prepared for the 50,000 POWs being held by the British in North Africa, the US needed to reactivate the Civilian Conservation Corps camps. They opened unused portions of several major military bases; utilizing such facilities as fairgrounds, racetracks, armories, and auditoriums; and setting up “tent cities” in remote areas of the country.

In the fall of 1942, knowing that they would need a better plan, they began the longer-range $50 million-dollar program of POW camp construction. The government had decided that for security reasons, the camps needed be located in remote and isolated areas. They didn’t want any camps to be built within 170 miles of the east and west coasts; nor within a 150-mile-wide zone along the Canadian and Mexican borders. They also forbade locations near shipyards, munitions plants, and other vital wartime industries due to fears of sabotage. These regulations made the ideal site, according to the Army Corps of Engineers, an area of 350 acres of level and well-drained land located within five miles of a railroad and 500 feet from any public road. Wyoming and other rural states became the prime locations, hence Camp Douglas. Another reason for placing the POW camps in the United States, was that it also abided by the international Geneva Convention agreements, which were signed by 47 world powers in 1929, and defined treatment of enemy prisoners. The USA made a much greater attempt to live up to the pact than the Axis powers. According to interpretation by American military leaders, camps had to be constructed to the minimum standards of a regular military compound. That insured that the prisoners had adequate housing, food, and water to sustain life and in the end, they were treated so humanely, and after the war many of them would have loved to just stay here. Wyoming was not opposed to a POW camp within its borders, because the presence of a large POW camp would provide an economic boon to a state and the nearby communities so “Chambers of Commerce, businessmen, the Commerce and department, city mayors, and the state’s political leaders sought to secure the establishment of military installations” in Wyoming, according to historian TA Larson. These lobbying efforts resulted in the construction of a new air base at Casper, a large expansion at Cheyenne’s Fort FE Warren, and the selection of a site on the outskirts of the small town of Douglas as the location for a POW camp.

The Douglas site met the defense regulations and was quickly approved. It was located in Converse County within one mile of a rail line that passed through downtown Douglas. The 687-acre site sat above the banks of the North Platte River. The federal government acquired the land through condemnation, which brought about a legal battle in which the defendants were eventually awarded more money for their land than the government had initially proposed. The government was rather between a rock and a hard place. They wanted the contracts for the site. In December of 1942, government surveyors and engineers arrived in Douglas, fueling rumors of the proposed POW camp although the official announcement did not come until January of 1943. The low bid came from Peter Kiewit and Sons of Omaha, Nebraska, and the company set up operations in Douglas by February of 1943. Four to five hundred construction workers used the 4-H buildings on the state fairgrounds as dorms and a dining hall. The government contract specified the buildings be completed within 120 days. Kiewit and Sons actually finished the job in 95 days. “The officers’ quarters, clubhouse, and softball field were located at the north main entrance to the camp, outside the double rows of wired fencing (the inner fence was electrified) and guard towers that surrounded the rest of the complex. The hospital area and the troop barracks were built directly inside the fence. Beyond that, the prison complex was organized into three compounds, separated by wire electrified fencing, each with a capacity of approximately one thousand men. Auxiliary areas for prisoners included a large outdoor recreation area near the river, a softball field, and one football field. The camp also accommodated a variety of operational functions in buildings designed for the motor pool, a heating plant, warehouses, corrals, a K-9 dog unit, a sewage disposal plant, as well as a salvage yard and gravel pit.”

The influx of people prompted the Douglas mayor to urge local residents to rent any spare rooms in their houses to the incoming military personnel and their families as a housing crunch was inevitable in the town. The town leaders with the home front war effort quickly established a Service Men’s Center in the downstairs room of the Moose Lodge. Moose members cleaned and remodeled the room while the ladies of the lodge scrounged up furniture and curtains from local donations. It was a concerted effort to welcome the new facility and its personnel. The Moose Lodge basement became a popular hangout for servicemen with daily hours from 5pm until midnight and stayed open till 2am on Saturday nights. The Center was affiliated with the national USO organization during the final days of the war. The local newspaper focused on the anticipation and excitement of the arrival of the US Army coming to their town, especially the officers, which helped to downplay any apprehension people may have felt about having an enemy population one mile away that outnumbered the townsfolk. Because so many of Wyoming’s men, like many other states, were serving in the war, it was decided that the prisoners could fill in some of the gaps outside the camp. Wyoming was left with a critical shortage of agricultural labor. POWs provided the solution to the problem and performed many essential jobs related to agriculture. They harvested crops, whether it was cotton in the South or sugar beets and timber in Wyoming. Local ranchers and farmers formed a corporation, in anticipation of the much-needed prison labor. A manager was appointed to handle the governmental red tape involved in the contracting procedures.

The story of this POW camp is an important part of the history of the town of Douglas. While Camp Douglas is no longer in use, there are still a few remaining structures. The walls of the Officer’s Club were painted with murals by three of the Italian prisoners. They are beautiful murals that depict western life and folklore. They are now registered with the United States Department of the Interior National Park Service on the National Register of Historic Places.

The story of this POW camp is an important part of the history of the town of Douglas. While Camp Douglas is no longer in use, there are still a few remaining structures. The walls of the Officer’s Club were painted with murals by three of the Italian prisoners. They are beautiful murals that depict western life and folklore. They are now registered with the United States Department of the Interior National Park Service on the National Register of Historic Places.

My uncle, Bill Beadle, spent much of his working life in the pipe yards. Later, he owned his own rathole drilling business with his sons, Forrest and Steve, by his side. While Uncle Bill was a great machinist and an all-around mechanic, he truly loved fishing and bird hunting in the Worland area with his son, Steve the best. I am certain that is also why Uncle Bill was so content, in his later years, to live with Steve, his wife, Wanda, and their family. I can imagine they spent a lot of time discussing their fishing trips and their time walking the fields hunting for pheasants and chukars. Uncle Bill enjoyed hunting them because it was so exciting to walk the fields, waiting for that unexpected bird to fly up out of nowhere. The hunter had only seconds to react and would succeed only if he was truly skilled. Uncle Bill was truly skilled.

My uncle, Bill Beadle, spent much of his working life in the pipe yards. Later, he owned his own rathole drilling business with his sons, Forrest and Steve, by his side. While Uncle Bill was a great machinist and an all-around mechanic, he truly loved fishing and bird hunting in the Worland area with his son, Steve the best. I am certain that is also why Uncle Bill was so content, in his later years, to live with Steve, his wife, Wanda, and their family. I can imagine they spent a lot of time discussing their fishing trips and their time walking the fields hunting for pheasants and chukars. Uncle Bill enjoyed hunting them because it was so exciting to walk the fields, waiting for that unexpected bird to fly up out of nowhere. The hunter had only seconds to react and would succeed only if he was truly skilled. Uncle Bill was truly skilled.

Uncle Bill Beadle was a unique individual. He had a deep love for all things western, and particularly the Old West. It is possible that he even felt he should have been living in the era. It is not that God made a mistake by placing him in the wrong time, but sometimes our personal preferences make us feel as though we might have been better suited to a different era. His family would have disagreed with him, had he suggested that he should have lived in the Old West…mostly because we wouldn’t have wanted him not to be with us. For Uncle Bill, it was not about living in the Old West, but about his love for Wyoming, which he truly did. Nevertheless, he was a cowboy at heart and would have loved to spend time in the Old West, even if it had only been a short time…like “Back to the Future!!”

Uncle Bill was always entertaining and humorous, and I enjoyed visiting with him. When his memory began to decline, Uncle Bill could no longer attend family gatherings, and as many elderly people, he struggled to communicate with family members, and it became easier for him to stay home rather than attempt to engage in conversations. I truly miss those times with Uncle Bill. Today would have been Uncle Bill’s 96th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Bill. We love and miss you very much.

Many people hate, or at least really dislike winter, but the cold and snow we normally see really isn’t so bad…at least not when compared to “the worst winter in the West,” which took place in 1886. During one of the harshest days of the “worst winter in the West,” nearly an inch of snow fell every hour for 16 hours, placing increased stress on the already starving cattle’s ability to find food.

Many people hate, or at least really dislike winter, but the cold and snow we normally see really isn’t so bad…at least not when compared to “the worst winter in the West,” which took place in 1886. During one of the harshest days of the “worst winter in the West,” nearly an inch of snow fell every hour for 16 hours, placing increased stress on the already starving cattle’s ability to find food.

Harsh winters in Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas was nothing new, but underestimating the coming winter can lead to disaster. The plains ranchers had seen severe winters in the past, but they had survived because their cattle were well-fed into the winter. By the mid-1880s, however, the situation had changed, and the winters had become mild. In hopes of making quick and easy money, greedy speculators had stocked the northern ranges in Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas. Deceived by the prior series of mild winters, many ranch managers had stopped putting up any winter feed. Then, in 1886, disaster struck.

The disaster began when that summer was hot and dry. Draught is often a precursor to big problems. By autumn, the range was almost barren of grass. That was bad enough, but then came the cold and snow, which came early. By January, record-breaking snowfalls blanketed the plains, forcing the already weakened cattle to expend vital energy just moving through the snow in search of the already scant forage. In January, a warm Chinook wind briefly melted the top layers of snow. The “January Thaw” is a well know phenomenon is this area. When the brutal cold returned…so brutal, that some ranches recorded temperatures of 63 below zero, a hard, thick shell of ice formed over the ground, making it almost impossible for the cattle to break through the snow to reach the meager amount of grass below. Unfortunately, the ranchers had become complacent, and with no winter hay stored to feed the animals, many ranchers had to sit by idly and watch their herds slowly starve to death. According to one historian, “Starving cattle staggered through village streets, and collapsed and died in dooryards.” In Montana, 5,000 head of cattle invaded the outskirts of Great Falls, eating the saplings the townspeople had planted that spring and “bawling for food.”

When the snow melted in the spring, the carcasses of the massive herds dotted the land as far as the eye could see. One observer noted that many rotting carcasses clogged the creeks and rivers, so that it was difficult to find water fit to drink. Millions of cattle are estimated to have died during the “Great Die-Up,” in a grimly humorous reference to the celebrated “Round-Up.” Montana ranchers alone lost an estimated 362,000 head of cattle, which was more than half of the territory’s herd.

The ill planned for disaster sent hundreds of area ranches into bankruptcy. The hard winter also brought an abrupt end to the era of the open range. Realizing that they could not predict future weather, the ranchers now understood that they would always need to grow crops to feed their animals, both in summer and winter. Ranchers began to reduce the size of their herds and to stretch barbed wire fences across the open range to

enclose their new hay fields. By the 1890s, the typical rancher was, out of necessity, also a farmer. Cowboys began to spend more time fixing fences than riding herd or roping yearlings. Hard lessons learned, but eventually, new settlers to the West understood that they had to adapt to the often-harsh demands of life on the western plains, if they were to survive and thrive.

enclose their new hay fields. By the 1890s, the typical rancher was, out of necessity, also a farmer. Cowboys began to spend more time fixing fences than riding herd or roping yearlings. Hard lessons learned, but eventually, new settlers to the West understood that they had to adapt to the often-harsh demands of life on the western plains, if they were to survive and thrive.

It so hard for me to believe that my niece, Jessi Sawdon is celebrating her 40th birthday. I remember the day she was born. She was such a cutie, and as he grew, her personality shown through. Jessi is the firstborn of my sister, Allyn Hadlock and her husband, Chris Hadlock’s four children. Jessi is a very social person, and for her, every day is a celebration…and Jessi does love to celebrate!! Her sister, Lindsay says, “She’s a good aunt. Mackenzie always has fun when we go over there or if she goes to stay the night. She’s has really settled in Cheyenne…finding a great church, making some new friends, and getting into a rhythm. She’s gotten really involved in her church and her family has been growing spiritually.” Lindsay and her family live in Laramie, Wyoming, which is a little over half an hour drive from Jessi and her family in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The closeness has made it possible for Lindsay’s daughter, Mackenzie and Jessi’s daughter, Adelaide to be really good friends, and for Jessi and Lindsay to be close sisters too.

It so hard for me to believe that my niece, Jessi Sawdon is celebrating her 40th birthday. I remember the day she was born. She was such a cutie, and as he grew, her personality shown through. Jessi is the firstborn of my sister, Allyn Hadlock and her husband, Chris Hadlock’s four children. Jessi is a very social person, and for her, every day is a celebration…and Jessi does love to celebrate!! Her sister, Lindsay says, “She’s a good aunt. Mackenzie always has fun when we go over there or if she goes to stay the night. She’s has really settled in Cheyenne…finding a great church, making some new friends, and getting into a rhythm. She’s gotten really involved in her church and her family has been growing spiritually.” Lindsay and her family live in Laramie, Wyoming, which is a little over half an hour drive from Jessi and her family in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The closeness has made it possible for Lindsay’s daughter, Mackenzie and Jessi’s daughter, Adelaide to be really good friends, and for Jessi and Lindsay to be close sisters too.

For my sister, Allyn, this birthday has been one of reflection. Allyn says, “Jessi celebrated her 40th this year!!

Looking back over the years, I see how fun and smart and strong she is!! ‘Girls just wanna have fun’ really describes her!! She is a good wife and a terrific mother. She loves to be on the move, going camping, to museums, hiking, any downtown activities, she’s all about it. This year she wanted to celebrate as much as she could so her, and a bunch of friends went out to Napa California and toured some wineries, stayed in an air BNB, and really had a great time. They sat in the hot tub, toured the golden gate bridge area, and one of the girls had an aunt and uncle who live out there and they gave the girls the royal treatment with an all-day cruise around San Francisco Bay in their yacht! They fed them breakfast and lunch on the boat and Jessi says it was definitely a highlight of their trip. They were so kind and really made it special for the girls!!”

Looking back over the years, I see how fun and smart and strong she is!! ‘Girls just wanna have fun’ really describes her!! She is a good wife and a terrific mother. She loves to be on the move, going camping, to museums, hiking, any downtown activities, she’s all about it. This year she wanted to celebrate as much as she could so her, and a bunch of friends went out to Napa California and toured some wineries, stayed in an air BNB, and really had a great time. They sat in the hot tub, toured the golden gate bridge area, and one of the girls had an aunt and uncle who live out there and they gave the girls the royal treatment with an all-day cruise around San Francisco Bay in their yacht! They fed them breakfast and lunch on the boat and Jessi says it was definitely a highlight of their trip. They were so kind and really made it special for the girls!!”

Then, her husband, Jason threw her 40th birthday party out at the Hangar, in Casper, Wyoming, and we celebrated her all evening. Allyn and Chris helped him plan the party, and it really turned out nice. Last Thursday, they were back in town for Jessi’s company Christmas party, and we gave her a birthday dinner here on Friday night with grilled steak, potatoes, and roasted veggies. Allyn really hopes she had the 40th year of her dreams, and she knows the fun will continue because “she just wants to have fun!!” Truer words were never spoken. Jessi is a fun-loving person and always put a smile on your face. Today is Jessi’s 40th birthday!! Happy birthday Jessi!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Our uncle, Eddie Hein, was always a man you could count on. He was hard working and always willing to help someone in need. He would even travel to help. When my in-laws, Walt and Joann Schulenberg, were building their house in Homa Hills, Eddie came down from Forsyth, Montana to Casper, Wyoming to help lay the cinder blocks. It was a big job, and while the whole family helped out, we didn’t really know how to lay brick. My father-in-law and his brother, Eddie did. I suppose we would have finished the house one way or the other, but it would have taken a lot longer.

Our uncle, Eddie Hein, was always a man you could count on. He was hard working and always willing to help someone in need. He would even travel to help. When my in-laws, Walt and Joann Schulenberg, were building their house in Homa Hills, Eddie came down from Forsyth, Montana to Casper, Wyoming to help lay the cinder blocks. It was a big job, and while the whole family helped out, we didn’t really know how to lay brick. My father-in-law and his brother, Eddie did. I suppose we would have finished the house one way or the other, but it would have taken a lot longer.

Eddie was that way with everyone. If people called, he did his best to help. I’m certain that when he passed

away, on October 16, 2019, the loss to the town of Forsyth was deeply felt. I know it was deeply felt in our family…not because of what Eddie might do for us, but for who he was. Eddie wasn’t just the guy who could get the job done, he was kind and caring, a friend to all who knew him, and a wonderful family man. He was very close to his children, Larry Hein and Kim Arani, his grandkids, Dalton Hein and Destiny Wallace, and of course, his loving wife, Pearl, of 52 years at the time of his passing. His family always knew that they were his priority.

away, on October 16, 2019, the loss to the town of Forsyth was deeply felt. I know it was deeply felt in our family…not because of what Eddie might do for us, but for who he was. Eddie wasn’t just the guy who could get the job done, he was kind and caring, a friend to all who knew him, and a wonderful family man. He was very close to his children, Larry Hein and Kim Arani, his grandkids, Dalton Hein and Destiny Wallace, and of course, his loving wife, Pearl, of 52 years at the time of his passing. His family always knew that they were his priority.

Eddie worked at Peabody coal mine in Colstrip, Montana until his retirement. He was well respected and loved by bosses and coworkers alike. They always knew that if Eddie Hein was on the job, he would give it his full

attention and full effort. He worked hard, and very much earned his retirement. Anyone who worked in mining can attest to that for sure. After his retirement, Eddie and Pearl loved to relax at their home in Forsyth, visit their daughter Kim and her husband Michael, in Texas, and I’m sure Eddie pitched in at Larry’s shop too. Unfortunately, all that was cut short by a stroke, and later the heart attack that took Eddie’s life in 2019. That was such a sad day for all of us. Today would have been Eddie’s 81st birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Eddie. We love and miss you very much.

attention and full effort. He worked hard, and very much earned his retirement. Anyone who worked in mining can attest to that for sure. After his retirement, Eddie and Pearl loved to relax at their home in Forsyth, visit their daughter Kim and her husband Michael, in Texas, and I’m sure Eddie pitched in at Larry’s shop too. Unfortunately, all that was cut short by a stroke, and later the heart attack that took Eddie’s life in 2019. That was such a sad day for all of us. Today would have been Eddie’s 81st birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Eddie. We love and miss you very much.