World War II

Since the earliest beginnings of Israel, the Arab community has been protesting its existence and trying to remove it from the face of the Earth. I don’t particularly understand what their problem uis. Given the tiny size of Israel compared to the vastness of the Arab nations, why is it so hard to allow them to live in peace? It is, of course a Holy War situation that is unlikely to go away for as long as time continues.

Since the earliest beginnings of Israel, the Arab community has been protesting its existence and trying to remove it from the face of the Earth. I don’t particularly understand what their problem uis. Given the tiny size of Israel compared to the vastness of the Arab nations, why is it so hard to allow them to live in peace? It is, of course a Holy War situation that is unlikely to go away for as long as time continues.

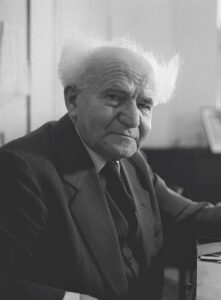

Israel had been a nation way, way back, but when they were taken into captivity, they were scattered to many nations. Once they were freed, they traveled to Israel (I think most people know the Exodus story). Of course, their existence was fought over again and again, finally leading up to the Holocaust. When World War II ended, many of the Jewish people again moved to and populated the Israeli land, but it wasn’t until May 14, 1948, that David Ben-Gurion, the head of the Jewish Agency, proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel. United States President Harry S Truman recognized the new nation on the same day. Since that time, there have been multiple wars and continuing conflicts that have threatened the existence of the Israeli state.

One such war was the Six-Day War, also called June War or Third Arab-Israeli War or Naksah. It was a short-lived war that took place from June 5, 1967 to June 10, 1967. It was the third of the Arab-Israeli wars. The first took place almost immediately after they were declared a state. The Israeli people have learned to fight for survival all their lives, vowing never to allow another Holocaust to be carried out. Israel’s decisive victory in the Six-Day War included the capture of the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank, Old City of Jerusalem, and Golan Heights. Of course, things didn’t end there. The fact that these territories belonged to Israel has been a major point of contention in the Arab-Israeli conflict sin that time.

The Six-Day War had precursors, as most wars do. Prior to the start of the war, the Palestinian guerrilla groups based in Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan randomly began attacking Israel, basically lobbing missiles at them, leading to costly

Israeli reprisals. Then, in November 1966 an Israeli strike on the village of Al-Sam in the Jordanian West Bank left 18 dead and 54 wounded, and during an air battle with Syria in April 1967, the Israeli Air Force shot down six Syrian MiG fighter jets. Soviet intelligence reports in May claimed that Israel was planning a campaign against Syria, and although these claims were inaccurate, the accusations further heightened tensions between Israel and its Arab neighbors.

Israeli reprisals. Then, in November 1966 an Israeli strike on the village of Al-Sam in the Jordanian West Bank left 18 dead and 54 wounded, and during an air battle with Syria in April 1967, the Israeli Air Force shot down six Syrian MiG fighter jets. Soviet intelligence reports in May claimed that Israel was planning a campaign against Syria, and although these claims were inaccurate, the accusations further heightened tensions between Israel and its Arab neighbors.

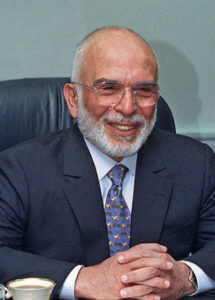

During this time, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser had come under sharp criticism for his refusing to become involved with Syria and Jordan against Israel. He was accused of hiding behind the United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) stationed at Egypt’s border with Israel in the Sinai. Under pressure, he moved to unambiguously demonstrate support for Syria on May 14, 1967. Nasser mobilized Egyptian forces in the Sinai on May 18, 1967 and formally requested the removal of the UNEF stationed there. On May 22, 1967, he closed the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping, thus instituting an effective blockade of the port city of Elat in southern Israel. On May 30, 1967, King Hussein of Jordan arrived in Cairo to sign a mutual defense pact with Egypt, placing Jordanian forces under Egyptian command. Iraq joined the alliance shortly thereafter.

As Israel became aware of the mobilization of its Arab neighbors, early on the morning of June 5, 1967, Israel took preemptive action and staged an air assault that destroyed more than 90 percent Egypt’s air force on the tarmac. A similar air assault incapacitated the Syrian air force. Without cover from the air, the Egyptian army was left vulnerable to attack. The domination in this war became apparent right away, and within three days the Israelis had achieved an overwhelming victory on the ground, capturing the Gaza Strip and all of the Sinai Peninsula up to the east bank of the Suez Canal.

Israel warned Jordan’s King Hussein to stay out of the conflict, but they disregarded the warning, and eastern front was also opened on June 5, 1967, when Jordanian forces began shelling West Jerusalem only to face a crushing

Israeli counterattack. On June 7, 1967, Israeli forces drove Jordanian forces out of East Jerusalem and most of the West Bank. By June 10, 1967, the war was over and Israel was the obvious winner. It seems to me that the Arab nations should heed the warnings of history, and leave Israel alone, but I suppose that is unlikely. Nevertheless, Israeli land belongs to the Jewish people by the promise of God and they would do well to let it go.

Israeli counterattack. On June 7, 1967, Israeli forces drove Jordanian forces out of East Jerusalem and most of the West Bank. By June 10, 1967, the war was over and Israel was the obvious winner. It seems to me that the Arab nations should heed the warnings of history, and leave Israel alone, but I suppose that is unlikely. Nevertheless, Israeli land belongs to the Jewish people by the promise of God and they would do well to let it go.

In a military operation, especially as part of a war, absolute secrecy is vital. Those involved with the planning have to know that they can trust everyone who is around them. One of the most important operations of World War II was the D-Day attack…Operation Overlord. Success was vital, and failure was simply not an option, no matter how many men were lost. The attack on Pearl Harbor had finally drawn the United States into World War II, and now we were in it to win it.

In a military operation, especially as part of a war, absolute secrecy is vital. Those involved with the planning have to know that they can trust everyone who is around them. One of the most important operations of World War II was the D-Day attack…Operation Overlord. Success was vital, and failure was simply not an option, no matter how many men were lost. The attack on Pearl Harbor had finally drawn the United States into World War II, and now we were in it to win it.

The success of any mission is found in the planning, so in August 1943, Franklin D Roosevelt and Winston Churchill met in Quebec for the first of two meetings code-named “Quadrant.” Technically, the meeting was the first of two “Quebec Conferences.” The meetings couldn’t even officially talk about the name of the actual operation, “Operation Overlord, which was later known as D-Day to the world. The Americans and the Brits had differences of opinion as to just how the operation was to be handled, but in order to make this operation work, they would have to be in complete agreement, and the mission would have to be kept completely covert!! No one could know the details.

Everyone, from the top men down to the paper supplier was screened to make sure of their loyalties. No stone was left unturned. If any information was leaked, thousands of men could die, and the fate of the world could have been severely compromised. Nevertheless, something was “missed” somehow. A young Canadian named Émile Couture was in charge of stationery supplies that fateful day, and in reality, he had no intention of being a traitor or playing any other nefarious part in the leak of information into the operation. Nevertheless, he managed to walk out of those meetings with the tactical plans for the invasions. It wasn’t even accidental…exactly.

Roosevelt and Churchill were excellent strategists, and their very detailed plans were perfectly laid out. The operation was going to be an amazing success. Now, all they had to do was to keep everything secret until the actual day, as yet unnamed, of the operation. The plans included detailed listings of Allied military assets to be used in the landings…the number of planes, combat cars, ships, and ground soldiers. They only had to keep it very quiet, because the leak of this information could have turned the tide of the war in favor of the Axis powers, and had that happened, our world would be vastly different even from the strange world we are experiencing today. Sergeant Major Émile Couture had been tasked with cleaning up after the meetings and instructed to make sure nothing was left behind.

Couture was doing his job in a meticulous fashion, but while cleaning an office on the third floor of the hotel, he discovered a leather portfolio that was inscribed “Churchill-Roosevelt, Quebec Conference, 1943. Maybe he thought it was just an empty portfolio, and so thought he could actually have an amazing souvenir of such a monumental meeting. Just think of the stories he could tell his children and grandchildren about the time he got to help out with such an important meeting between two of the most important men if his time. History doesn’t really tell us what he was thinking, but he decided to keep the portfolio as a souvenir without realizing what was actually in the portfolio.  Couture walked out of the Château Frontenac without anyone being any the wiser and drove to the cottage where he was living with his cousins in Lac-Beauport just a few miles outside of Quebec City. Then he took time to examine his “treasure” only to find that he could actually be tried for treason. Couture was more than frightened. He was terrified, and he hid the files under his mattress overnight.

Couture walked out of the Château Frontenac without anyone being any the wiser and drove to the cottage where he was living with his cousins in Lac-Beauport just a few miles outside of Quebec City. Then he took time to examine his “treasure” only to find that he could actually be tried for treason. Couture was more than frightened. He was terrified, and he hid the files under his mattress overnight.

In the morning, knowing that he would have to face the music, he took the portfolio and its files to his superior, Brigadier Edmond Blais. Blais told Couture to go home and wait. He would be dealt with in the morning. Couture could have been put in prison for the remainder of the war in order to make certain that he did not leak the information he had seen. He was, after all, a low-ranking soldier, and shouldn’t have access to such top-secret information. Instead, he was sent home after being questioned by Scotland Yard and the FBI.

Whether Couture was terrified to say anything, or just an honorable soldier, he never leaked the information he had seen. Blais must have liked Couture, because he sent a letter on August 28, 1943, in which he recommended the Sergeant Major Émile Couture be awarded “the greatest accomplishment that can be given an NCO (non-commissioned officer).

On June 6, 1944, the Allies staged the largest amphibious military landing in history. Always remembered as D-Day, Operation Overlord saw 150,000 troops hit the beaches of Normandy, push back the German army and set the course for the eventual victory of the Allied forces. The secret of D-Day was kept, and the operation went off without a hitch.

Couture was rewarded for his discretion during a ceremony in September 1944, when he was commended for his actions by being granted a British Empire Medal. During the ceremony, there was no mention of what Couture had actually done to merit the award other than “services rendered.” I wonder if anyone thought that odd. Nevertheless, they really couldn’t tell, because it would have been embarrassing to the military for the public to see how easily someone walked out of the hotel with top secret documents.

Couture’s daughter, Anne Couture, insists that her father never told anyone. But someone did leak the story, and Couture became the center of the media’s attention. He gave several interviews over time, but he never told anyone whose office he had been cleaning when he found the documents or who he thought might have left them there. Though, Anne admits, he may have told her mother. If he did, Georgette Larochelle isn’t telling anyone, and in an effort to clear the record concerning her husband’s involvement in the whole incident. She has turned over all the memorabilia and documentation the family has kept over the years. It has all been donated to the Royal Museum and has been displayed in an exhibit since the 75th anniversary of the 2nd

Quebec Conference.

Quebec Conference.

According to the museum’s director and curator, the documents are “convincing and some of the artifacts are considered invaluable” to the museum. He called the personal items which were specially made for the conference, “a great witness of this event of national significance.”

Following the end of World War II, many members of the Third Reich fled Germany, and relocated to Argentina this had all been planned as it became more and more clear that the Nazi Regime would not be successful. The ultimate plan was to lay low for a while, and then form a new Third Reich, or more likely the Fourth Reich. The main figures of the Third Reich were given new identities and smuggled out as soon as they could. It is unknown just exactly how many made it out, but files discovered in Argentina reveal the names of 12,000 Nazis who lived there in the 1930s, many of whom had Swiss bank accounts.

Following the end of World War II, many members of the Third Reich fled Germany, and relocated to Argentina this had all been planned as it became more and more clear that the Nazi Regime would not be successful. The ultimate plan was to lay low for a while, and then form a new Third Reich, or more likely the Fourth Reich. The main figures of the Third Reich were given new identities and smuggled out as soon as they could. It is unknown just exactly how many made it out, but files discovered in Argentina reveal the names of 12,000 Nazis who lived there in the 1930s, many of whom had Swiss bank accounts.

The Jewish people were understandably furious at not only the atrocities that their people had been subjected to, but the fact that with the escape, the fact is that many of the Nazi criminals would never answer for what they did, much less be punished for those atrocities. Nevertheless, the initial intent was to seek justice.

So, on December 13, 1949, Mossad was established. It later became the Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations. While Mossad has many uses today, it was primarily designed to go out and get the war criminals who were in hiding in Argentina and other parts of South America,  where there was no extradition. Mossad planned to go in without authorization, kidnap the Nazi war criminals, and take them to Israel to stand trial.

where there was no extradition. Mossad planned to go in without authorization, kidnap the Nazi war criminals, and take them to Israel to stand trial.

Some people may assume that Israel’s vaunted Mossad intelligence service devoted a great deal of energy to hunting for Nazis to seek revenge for the Holocaust. That was not the case. The desire to bring the murderers of Jews to justice was not deemed as important to Israel’s leaders in the early years of statehood as more pressing issues directly effecting the nation’s security. One of those issues, was preventing Nazis who went to Egypt from aiding in Nasser’s development of missile technology.

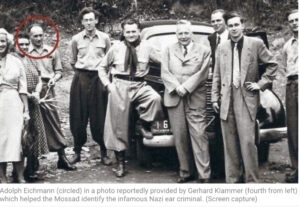

There were a few of the war criminals that the Mossad brought to Justice. One well known criminal was Adolf Eichmann, the man who engineered the Final Solution. His “contribution” to the atrocity that was the Holocaust was one of the most heinous. In 1960, Mossad tracked Eighmann to his home in Argentina, kidnapped him, and brought  him to trial in Israel. He was convicted of war crimes and was actually the only person ever sentenced to death in Israel. The Argentinian government was furious because their no extradition policy was violated by Mossad. The immediately demanded that Israel return Eichmann, and then asked for reparations for Eichmann’s seizure by Mossad agents in Buenos Aires. Nevertheless, on August 2, 1969 the dispute was resolved by Israel keeping Eichmann, but acknowledging that Argentina’s fundamental rights had been infringed upon. No further repercussions were given.

him to trial in Israel. He was convicted of war crimes and was actually the only person ever sentenced to death in Israel. The Argentinian government was furious because their no extradition policy was violated by Mossad. The immediately demanded that Israel return Eichmann, and then asked for reparations for Eichmann’s seizure by Mossad agents in Buenos Aires. Nevertheless, on August 2, 1969 the dispute was resolved by Israel keeping Eichmann, but acknowledging that Argentina’s fundamental rights had been infringed upon. No further repercussions were given.

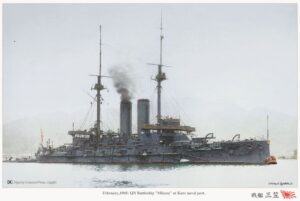

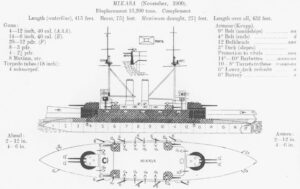

It is not usually my habit to talk about the spectacular ships built by our nation’s enemies, but IJN Mikasa might be a worthy exception. The Mikasa is a “pre-dreadnought” battleship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in the late 1890s and is the only ship of her class. I didn’t know what a “pre-dreadnought” ship was, so I looked into it. “Pre-dreadnoughts were battleships built before 1906, when HMS Dreadnought was launched. Dreadnoughts were more powerful battleships that followed the design of HMS Dreadnought and so made pre-dreadnoughts obsolete.” The ship displaced over 15,000 long tons, with a crew of over 800 men.

It is not usually my habit to talk about the spectacular ships built by our nation’s enemies, but IJN Mikasa might be a worthy exception. The Mikasa is a “pre-dreadnought” battleship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) in the late 1890s and is the only ship of her class. I didn’t know what a “pre-dreadnought” ship was, so I looked into it. “Pre-dreadnoughts were battleships built before 1906, when HMS Dreadnought was launched. Dreadnoughts were more powerful battleships that followed the design of HMS Dreadnought and so made pre-dreadnoughts obsolete.” The ship displaced over 15,000 long tons, with a crew of over 800 men.

While she might not have been as powerful, IJN Mikasa was nevertheless a well-built ship, that was able to withstand more than most ships of her time. Named after Mount Mikasa in Nara, Japan, she served as the flagship of Vice Admiral Togo Heihachiro throughout the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. That war included the Battle of Port Arthur, which occurred on the second day of the war, as well as the Battles of the Yellow Sea and Tsushima. Just a few days after the Russo-Japanese War ended, Mikasa’s magazine (a ship’s magazine is where the powder and shells are stored) suddenly exploded and sank the ship. The explosion killed 251 men. Shortly before the Mikasa’s fatal accident, the ship had been involved in the  Battle of Tsushima (May 27, 1905), during which she had shrugged off over 40 shell strikes from heavy Russian naval guns! In that battle 113 of her crew were killed or injured. While such an event would usually mean the end of a ship, IJN Mikasa was salvaged, and while her repairs took over two years to complete, she went on to serve as a coast-defense ship during World War I, and she supported Japanese forces during the Siberian Intervention in the Russian Civil War. Ironically, in 1912 a despondent sailor among her crew tried to blow the ship up once again while the ship was anchored at Kobe. In the end the ship served until 1923, after being pulled up from the drink, repaired, and recommissioned.

Battle of Tsushima (May 27, 1905), during which she had shrugged off over 40 shell strikes from heavy Russian naval guns! In that battle 113 of her crew were killed or injured. While such an event would usually mean the end of a ship, IJN Mikasa was salvaged, and while her repairs took over two years to complete, she went on to serve as a coast-defense ship during World War I, and she supported Japanese forces during the Siberian Intervention in the Russian Civil War. Ironically, in 1912 a despondent sailor among her crew tried to blow the ship up once again while the ship was anchored at Kobe. In the end the ship served until 1923, after being pulled up from the drink, repaired, and recommissioned.

IJN Mikasa was decommissioned on September 23, 1923, following the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. At that time, she was scheduled for destruction, but at the request of the Japanese government, each of the signatory countries to the treaty agreed that Mikasa could be preserved as a memorial ship. The agreement required that her hull be encased in concrete. On November 12, 1926, Mikasa was opened for display in Yokosuka in the presence of Crown Prince Hirohito and Togo. Unfortunately, the ship deteriorated under the  control of the occupation forces after the surrender of Japan in 1945. Finally, in 1955, American businessman John Rubin, who had formally lived in Barrow, England, wrote a letter to the Japan Times about the state of the ship. His letter served as the catalyst for a new restoration campaign. The Japanese public, who were widely onboard with the idea, supported the project, as did Fleet Admiral Chester W Nimitz. The ship was once again restored, and the museum version reopened in 1961. On August 5, 2009, IJN Mikasa was repainted by sailors from USS Nimitz, and she is now the only surviving example of a “pre-dreadnought” battleship in the world. IJN Mikasa is located in the town of its construction, Barrow-in-Furness, near Mikasa Street on Walney Island.

control of the occupation forces after the surrender of Japan in 1945. Finally, in 1955, American businessman John Rubin, who had formally lived in Barrow, England, wrote a letter to the Japan Times about the state of the ship. His letter served as the catalyst for a new restoration campaign. The Japanese public, who were widely onboard with the idea, supported the project, as did Fleet Admiral Chester W Nimitz. The ship was once again restored, and the museum version reopened in 1961. On August 5, 2009, IJN Mikasa was repainted by sailors from USS Nimitz, and she is now the only surviving example of a “pre-dreadnought” battleship in the world. IJN Mikasa is located in the town of its construction, Barrow-in-Furness, near Mikasa Street on Walney Island.

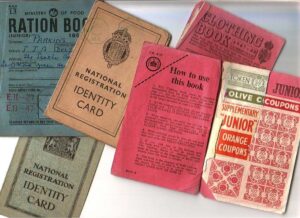

When nations go to war, it is not just the soldiers fighting, who pay the price. War is expensive, and everyone has to help with the war effort. The American people are famous for pitching in when “push comes to shove” and World War II would be no different. On May 15, 1942, the American war effort needed the American citizens to “tighten their belts” so that the funds could be used to help our soldiers. So, gasoline rationing began in 17 Eastern states. It was the first attempt to help the American war effort during World War II. President Franklin D Roosevelt then ensured that by the end of the year, mandatory gasoline rationing was in effect in all 48 states. Things got tougher, and the people felt the pinch, but they were willing to do what was necessary to win the war.

When nations go to war, it is not just the soldiers fighting, who pay the price. War is expensive, and everyone has to help with the war effort. The American people are famous for pitching in when “push comes to shove” and World War II would be no different. On May 15, 1942, the American war effort needed the American citizens to “tighten their belts” so that the funds could be used to help our soldiers. So, gasoline rationing began in 17 Eastern states. It was the first attempt to help the American war effort during World War II. President Franklin D Roosevelt then ensured that by the end of the year, mandatory gasoline rationing was in effect in all 48 states. Things got tougher, and the people felt the pinch, but they were willing to do what was necessary to win the war.

After World War I, many Americans were less than enthusiastic about entering another world war, at least until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The day after the attack, Congress almost unanimously approved Roosevelt’s request for a declaration of war against Japan and three days later Japan’s allies Germany and Italy declared war against the United States. Like it or not, war was on. With the onset of  war, Americans almost immediately felt the impact of the war. The economy quickly shifted from a focus on consumer goods into full-time war production. Everyone was pitching in, and everyone was willing. With so many men in now in the fighting, the women went to work in the factories to replace the now enlisted men, automobile factories began producing tanks and planes for Allied forces and households were required to limit their consumption of such products as rubber, gasoline, sugar, alcohol, and cigarettes. Anything that might be needed for the war effort, was sacrificed by the American people, who felt like it was them just doing their part…for the most part.

war, Americans almost immediately felt the impact of the war. The economy quickly shifted from a focus on consumer goods into full-time war production. Everyone was pitching in, and everyone was willing. With so many men in now in the fighting, the women went to work in the factories to replace the now enlisted men, automobile factories began producing tanks and planes for Allied forces and households were required to limit their consumption of such products as rubber, gasoline, sugar, alcohol, and cigarettes. Anything that might be needed for the war effort, was sacrificed by the American people, who felt like it was them just doing their part…for the most part.

A number of commodities were rationed. Rubber was the first to go, after the Japanese invasion of the Dutch East Indies cut off the US supply. The shortage of rubber, of course affected the availability of products such as tires and anything else that used rubber. Gasoline was a given, because it would be needed to move the troops. Also, it was thought that less gasoline, would bring less travel and therefore less wear and tear on rubber tires. At first, the government urged voluntary gasoline rationing, but by the spring of 1942 it was obvious that people wouldn’t assume that their use was extravagant and not a frivolous use. Hense, first 17 states put mandatory gasoline rationing into effect, and by December, controls were extended across the entire country.

The Government issued ration stamps for gasoline were issued by local boards and pasted to the windshield of  a family or individual’s automobile. The type of stamp determined the gasoline allotment for that automobile. Black stamps signified non-essential travel and so allowed no more than three gallons per week. Red stamps were for workers who needed more gas, including policemen and mail carriers. With the restrictions, gasoline became a hot commodity on the black market, while legal measures of conserving gas, like carpooling, became the norm. Another Government mandated method to reduce gas consumption, the government passed a mandatory wartime speed limit of 35 mph, known as the “Victory Speed.” Things got tight in many areas, but the American people ultimately persevered, and the war effort supplied the needed commodities.

a family or individual’s automobile. The type of stamp determined the gasoline allotment for that automobile. Black stamps signified non-essential travel and so allowed no more than three gallons per week. Red stamps were for workers who needed more gas, including policemen and mail carriers. With the restrictions, gasoline became a hot commodity on the black market, while legal measures of conserving gas, like carpooling, became the norm. Another Government mandated method to reduce gas consumption, the government passed a mandatory wartime speed limit of 35 mph, known as the “Victory Speed.” Things got tight in many areas, but the American people ultimately persevered, and the war effort supplied the needed commodities.

As World War II, was winding down, the Nazis, is typical form were holding high-profile French prisoners of war at Itter Castle in Austria. The Nazis were notorious for their terribly abusive treatment of prisoners. When it became obvious that all was lost, in May 1945, the prison’s guards fled and left Itter Castle waiting for a unit of Waffen-SS police, who were sent in to wipe out the French prisoners and carry out reprisals against the local population for any hints of surrender. It was the Nazi way. When the proof of your war crimes is obvious, remove all evidence, including people, so that no one can tell the gruesome story.

As World War II, was winding down, the Nazis, is typical form were holding high-profile French prisoners of war at Itter Castle in Austria. The Nazis were notorious for their terribly abusive treatment of prisoners. When it became obvious that all was lost, in May 1945, the prison’s guards fled and left Itter Castle waiting for a unit of Waffen-SS police, who were sent in to wipe out the French prisoners and carry out reprisals against the local population for any hints of surrender. It was the Nazi way. When the proof of your war crimes is obvious, remove all evidence, including people, so that no one can tell the gruesome story.

There were, however, some good people in the German Army. One was an officer named Josef “Sepp” Gangl, who opposed the Nazis. Gangl had a small group of men who were loyal to him. Together they intervened to protect the prisoners and locals. Heavily outnumbered, Gangl sent word to the American forces in the area seeking aid. Gangl called for help, and he was answered by Captain John C “Jack” Lee Jr, who arrived with a band of volunteers and a single Sherman tank. It was such a strange group of enemies, who found themselves working together for something that was more important than the war they were in…human lives. Working together were French prisoners, American troops, and Wehrmacht soldiers in an effort to bravely defended the castle against the SS. The French prisoners included former prime ministers, generals, tennis star Jean Borotra, and even Charles de Gaulle’s sister. This,  Operation Cowboy, was one of two known times during the war in which Americans and Germans fought side by side. That is such a shocking turn of events, in fact many called it the strangest battle of World War II. Nevertheless, while the tank was blown up, it that made no difference, and in the end, the SS weren’t able to breach the castle. By late afternoon, an American relief force arrived at Itter Castle and captured the SS unit. In the battle, there was only one casualty on the defending side. Sadly, Gangl was slain by a sniper while trying to spot the position of the anti-tank gun from an observation post. He had given his life so that others might live. It was a brave and heroic act.

Operation Cowboy, was one of two known times during the war in which Americans and Germans fought side by side. That is such a shocking turn of events, in fact many called it the strangest battle of World War II. Nevertheless, while the tank was blown up, it that made no difference, and in the end, the SS weren’t able to breach the castle. By late afternoon, an American relief force arrived at Itter Castle and captured the SS unit. In the battle, there was only one casualty on the defending side. Sadly, Gangl was slain by a sniper while trying to spot the position of the anti-tank gun from an observation post. He had given his life so that others might live. It was a brave and heroic act.

When the airmen went off to war, their hope was that their plane would be able to stand up to the attacks that would be coming their way. In World War II, big war planes were very new. The men who spent the war in them, needed a plane that would take a hit and keep on flying. They would love to have a flying suit of armor, but it also had to be able to fly. A plane that was too heavy, obviously wouldn’t fly, and yet, they needed a plane that could get hit with shrapnel or bullets and still stay in the air. They knew that they couldn’t make sure that every plane that was hit would make it home, but they needed as many as possible to do just that.

When the airmen went off to war, their hope was that their plane would be able to stand up to the attacks that would be coming their way. In World War II, big war planes were very new. The men who spent the war in them, needed a plane that would take a hit and keep on flying. They would love to have a flying suit of armor, but it also had to be able to fly. A plane that was too heavy, obviously wouldn’t fly, and yet, they needed a plane that could get hit with shrapnel or bullets and still stay in the air. They knew that they couldn’t make sure that every plane that was hit would make it home, but they needed as many as possible to do just that.

There were a number of planes that were considered almost indestructible, or at least as indestructible as it is possible to be for an airplane in a war zone. Two of them…the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC), and the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, a US 4-engine propeller bomber, manufactured from 1943 to 1946 and used throughout the Korean War, as well as World War II. The name “Fortress” was coined when B-17, with its heavy firepower and multiple machine gun emplacements, made its public debut in July 1935. A reporter for The Seattle Times, Richard Williams, exclaimed, “Why, it’s a flying fortress!” The Boeing Company saw the value of that name and immediately had it trademarked. The truth of the matter is, however, that the planes had the ability to take a hit and still bring their boys home most of the time, provided the damage wasn’t too heavy.

These heavy bombers are bomber aircraft capable of delivering the largest payload of bombs, as well as the longest range, which is takeoff to landing distance, of their era. For those reasons, the heavy bombers are  usually among the largest and most powerful military aircraft at any point in time. Nevertheless, as the 20th century wound down, the heavy bombers were largely superseded by strategic bombers. The strategic bombers were often smaller in size, which allowed for much longer ranges and by necessity, these were capable of delivering nuclear bombs. It was a sign of the times, but for all World War II buffs, like me, it was a sad end of an era. The newer planes are great, don’t get me wrong, but they just don’t have the presence, at least in my mind, that the World War II heavy bombers did. Those old planes had a grace that the newer stuff simply doesn’t have. I suppose that my love of the B-17, at least, stems from the fact that it was the plane that brought my dad home safely…so he could become my dad.

usually among the largest and most powerful military aircraft at any point in time. Nevertheless, as the 20th century wound down, the heavy bombers were largely superseded by strategic bombers. The strategic bombers were often smaller in size, which allowed for much longer ranges and by necessity, these were capable of delivering nuclear bombs. It was a sign of the times, but for all World War II buffs, like me, it was a sad end of an era. The newer planes are great, don’t get me wrong, but they just don’t have the presence, at least in my mind, that the World War II heavy bombers did. Those old planes had a grace that the newer stuff simply doesn’t have. I suppose that my love of the B-17, at least, stems from the fact that it was the plane that brought my dad home safely…so he could become my dad.

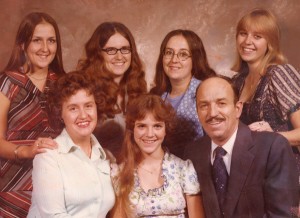

I have been studying a lot lately about World War II. It is my “favorite” war…if one can have a favorite war. My dad, Allen Spencer was a Staff Sergeant in World War II. He served as flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-17G, the flying fortress. The more I study World War II, the more I realize just how dangerous was…no matter what branch of the service a soldier was in. Dad’s family was one that didn’t have to suffer the loss of their soldier, because my dad came home after the war. He was the only one in his family that saw action in World War II, other than his half-brother, Norman Spencer. Dad’s older brother, Bill tried to serve, but due to flat feet and a hernia, he was turned down. My Uncle Bill was devastated by the rejection. My dad was his little brother, and he had always felt a need to protect him, not because Dad was accident prone or anything, but because he was his little brother. Now, he was going to have to let Dad go without the “backup” that Uncle Bill had hoped to provide. That was one of the hardest things my Uncle Bill ever had to do. So, Dad went with angel backup instead…and his mother’s prayers.

I have been studying a lot lately about World War II. It is my “favorite” war…if one can have a favorite war. My dad, Allen Spencer was a Staff Sergeant in World War II. He served as flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-17G, the flying fortress. The more I study World War II, the more I realize just how dangerous was…no matter what branch of the service a soldier was in. Dad’s family was one that didn’t have to suffer the loss of their soldier, because my dad came home after the war. He was the only one in his family that saw action in World War II, other than his half-brother, Norman Spencer. Dad’s older brother, Bill tried to serve, but due to flat feet and a hernia, he was turned down. My Uncle Bill was devastated by the rejection. My dad was his little brother, and he had always felt a need to protect him, not because Dad was accident prone or anything, but because he was his little brother. Now, he was going to have to let Dad go without the “backup” that Uncle Bill had hoped to provide. That was one of the hardest things my Uncle Bill ever had to do. So, Dad went with angel backup instead…and his mother’s prayers.

Dad served and returned home to his family, and because he did, my sisters and I, and our whole family exists.

Dad, like many of the soldiers in that generation, never spoke of his time in the service during World War II, and all we knew was what little we heard from his family, and a couple of newspaper articles. Knowing my dad as we did, those years were his duty, but never his desire. Dad was a gentle man, and the idea of killing must have weighed heavily on him. Nevertheless, he knew it was his duty, and he would never have shirked his duty. There were a number of heroic times in Dad’s time in the service. He actually saved his crew, when he cranked down the landing gear just in time to hit the runway. It must have been damaged by the anti-aircraft flak, because it wouldn’t come down. There were other times that his actions saved his crew, such as the enemy planes that he shot down. They were a good team. They were all heroes…every single one.

Dad, like many of the soldiers in that generation, never spoke of his time in the service during World War II, and all we knew was what little we heard from his family, and a couple of newspaper articles. Knowing my dad as we did, those years were his duty, but never his desire. Dad was a gentle man, and the idea of killing must have weighed heavily on him. Nevertheless, he knew it was his duty, and he would never have shirked his duty. There were a number of heroic times in Dad’s time in the service. He actually saved his crew, when he cranked down the landing gear just in time to hit the runway. It must have been damaged by the anti-aircraft flak, because it wouldn’t come down. There were other times that his actions saved his crew, such as the enemy planes that he shot down. They were a good team. They were all heroes…every single one.

While my dad was a hero during World War II, I will always consider his most important accomplishment, his family. Without my dad’s safe return from the war, we would not exist. He met my mom, Collene Byer Spencer when she was still a schoolgirl, but even then, they knew it was that forever love. They married in 1953, an

became the parents of five daughters, Cheryl, Masterson, Caryn Schulenberg (me), Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, and Allyn Hadlock. They went on to have grandchildren and great grandchildren…all of whom owe their lives to the fact that dad came home from war. For that I praise God, and I give Him all the glory. Today would have been my dad’s 99th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Dad. We love and miss you very much and look forward to seeing you again when we get to Heaven.

became the parents of five daughters, Cheryl, Masterson, Caryn Schulenberg (me), Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, and Allyn Hadlock. They went on to have grandchildren and great grandchildren…all of whom owe their lives to the fact that dad came home from war. For that I praise God, and I give Him all the glory. Today would have been my dad’s 99th birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Dad. We love and miss you very much and look forward to seeing you again when we get to Heaven.

While escape seemed impossible, there were a number of successful escapes from the horrific Nazi death camp known as Auschwitz. Unfortunately, there were also many failed attempts. These escapes and attempted escapes happened, because where people are held in captivity, they will rebel and try to find a way out, and when death is inevitable, escape become less risky. Hitler wanted all the Jews dead, and while he might have tried to hide his true intentions from the world, he certainly didn’t hide it from the Jews themselves.

While escape seemed impossible, there were a number of successful escapes from the horrific Nazi death camp known as Auschwitz. Unfortunately, there were also many failed attempts. These escapes and attempted escapes happened, because where people are held in captivity, they will rebel and try to find a way out, and when death is inevitable, escape become less risky. Hitler wanted all the Jews dead, and while he might have tried to hide his true intentions from the world, he certainly didn’t hide it from the Jews themselves.

Most prisoner escapes took place from worksites outside the camp. The attitude of local civilians was of immense importance in the success of these efforts. Some of the escapees tried to get the word out that the camps were not just work camps, but were also death camps, and that the people should fight with everything they had to avoid going. Of course, all too often, any reports were suppressed as much as possible by the Germans, and for the most part, the reports did little to no good.

On escape that particularly touched me was the escape of two Slovakian Jews, Rudolf Vrba (born Walter Rosenberg) and Alfred Wetzler, escaped in April 1944. They knew the consequences of the were caught, and the men in their barracks knew the consequences of helping them, or even being in the same barracks with them. Nevertheless, all of them felt that the risk was worth it to try to get the truth to the outside world.

Trust was vital, in an escape. Vrba and Wetzler came from the same town, so they knew each other well, and could trust each other. The men had been working on this escape idea for a while, coming up with plans and then rejecting them, because they couldn’t work. Finally, Wetzler came to Vrba with a plan that just might work. They would hide in a pile of wooden planks and after the three-day search for the escapees was finished,  they would escape and head South. The plan was good, but there were still a number of obstacles to maneuver. The first group to attempt the escape were later caught in a village south of the camp, but the wooden plank plan had worked, and the captured prisoners did not reveal their strategy.

they would escape and head South. The plan was good, but there were still a number of obstacles to maneuver. The first group to attempt the escape were later caught in a village south of the camp, but the wooden plank plan had worked, and the captured prisoners did not reveal their strategy.

So, Vrba and Wetzler waited two weeks, and put their plan in motion. The had a friend help them by pulling the planks over then, and covering the area with something to hid e the scent of the men from the dogs. The men expected the alarm to sound at the 5:30pm roll call, but no alarm sounded. The men began to think that someone had told of their location, and that the guards would be coming any minute, but the alarm went of shortly after 6:00pm and the sound of boots and dogs was everywhere. It was all they could do not to scream in terror. Nevertheless, they held their peace and stayed put.

The men laid motionless for three days with no food or water. They were stiff and cold, but finally, they heard the guards call off the search, so that night they decided to come out of the wood pile and make their escape. However, the planks wouldn’t budge. They pushed and pushed…almost to the point of panic. They determined that they would not die there, they gave it one last effort, and the planks gave way. They came out into the night, made their way to the nearest fence and crawled under the barbed wire. I’m quite sure they never wanted to see a fence again.

The ran for the woods, traveling at night, and hiding by day. They were seen by a few people, but thankfully everyone who saw them was sympathetic to their cause and helped them on their way. Finally, they crossed the

border, and they were free at last. They went to Zylina, where they met secretly with officials from the Slovakia Jewish Council and gave them a secret report on Auschwitz. An in-depth report was drawn up in Slovak and German. The plan was to get the report to the world before another train load of Jews could come to Auschwitz, and the men had done their part. They had done all they could. Unfortunately, the report did not get to those who needed to hear it, and the killing would go on until January 27, 1945, when Auschwitz was finally liberated.

border, and they were free at last. They went to Zylina, where they met secretly with officials from the Slovakia Jewish Council and gave them a secret report on Auschwitz. An in-depth report was drawn up in Slovak and German. The plan was to get the report to the world before another train load of Jews could come to Auschwitz, and the men had done their part. They had done all they could. Unfortunately, the report did not get to those who needed to hear it, and the killing would go on until January 27, 1945, when Auschwitz was finally liberated.

During World WarII, and probably any war, port cities are vital for the transportation of weapons, machinery, and personnel. The port city of Tobruk on Libya’s eastern Mediterranean coast is near the border with Egypt. In World War II, that may not have seemed like a particularly important port, but the Germans must have seen it as such, because in November of 1941, the Nazis laid siege to the capital of the Butnan District (previously the Tobruk District), and home to approximately 120,000 people today (although the population in 1941 was likely less).

During World WarII, and probably any war, port cities are vital for the transportation of weapons, machinery, and personnel. The port city of Tobruk on Libya’s eastern Mediterranean coast is near the border with Egypt. In World War II, that may not have seemed like a particularly important port, but the Germans must have seen it as such, because in November of 1941, the Nazis laid siege to the capital of the Butnan District (previously the Tobruk District), and home to approximately 120,000 people today (although the population in 1941 was likely less).

Tobruk began its existence as an ancient Greek colony, but later became a Roman fortress guarding the frontier of Cyrenaica. I suppose that qualifies as an important port. Tobruk became a waystation along the coastal caravan route, over the centuries. It became an Italian military post by 1911. Then, during World War II, Allied forces, mainly the Australian 6th Division, saw it a the perfect spot for a military base, and they took Tobruk on January 22, 1941. They reached Tobruk on April 9, 1941. At that time, there was prolonged fighting against German and Italian forces. Tobruk has a strong, naturally protected deep harbor. It is probably the best natural port in northern Africa. It wasn’t as popular, because it wasn’t near any landsites.

In 1941, Axis forces took over Tobruk, in a siege that would last for 241 days. The Axis forces advanced through Cyrenaica from El Agheila in Operation Sonnenblume against Allied forces in Libya, during the Western Desert Campaign of 1940–1943 in World War II. The Allies had defeated the Italian 10th Army during Operation Compass that took place between December 9, 1940 and February 9, 1941, and trapped the remnants of the troops at Beda Fomm. Much of the Western Desert Force (WDF) was sent to the Greek and Syrian campaign in early 1941. By the time German troops and Italian reinforcements reached Libya, only a skeleton Allied force remained, and they were short of equipment and supplies. It was then that the Australian 9th Division became known as “The Rats of Tobruk” when they pulled back to Tobruk to avoid encirclement after actions at Er

Regima and Mechili. Although the siege was lifted by Operation Crusader in November 1941, a renewed offensive by Axis forces under Erwin Rommel the following year resulted in Tobruk being re-captured in June 1942 and held by the Axis forces until November 1942, when it was finally recaptured by the Allies. Rebuilt after World War II, Tobruk was later expanded during the 1960s to include a port terminal linked by an oil pipeline to the Sarir oil field.

Regima and Mechili. Although the siege was lifted by Operation Crusader in November 1941, a renewed offensive by Axis forces under Erwin Rommel the following year resulted in Tobruk being re-captured in June 1942 and held by the Axis forces until November 1942, when it was finally recaptured by the Allies. Rebuilt after World War II, Tobruk was later expanded during the 1960s to include a port terminal linked by an oil pipeline to the Sarir oil field.