World War II

The Battle of Wake Island was a significant conflict in the Pacific theater of World War II, occurring on Wake Island. The attack began simultaneously with the assault on Pearl Harbor’s naval and air bases in Hawaii on the morning of December 8, 1941 (December 7th in Hawaii) and concluded on December 23rd with the American forces capitulating to the Empire of Japan. The battle took place on the atoll comprising Wake Island and its smaller islets, Peale and Wilkes, involving air, land, and sea forces of the Japanese Empire and the United States, with a notable presence of Marines from both nations. The Japanese forces were formidable, and the majority of the surviving Americans were transported from the island to POW camps by the Japanese. Ninety-seven were left behind to be used as forced labor. The Allies’ response involved intermittent bombing of the island, but no further land invasions occurred. This was in line with a broader Allied strategy to isolate certain Japanese-occupied islands in the South Pacific, effectively leaving them to wither in isolation.

The Battle of Wake Island was a significant conflict in the Pacific theater of World War II, occurring on Wake Island. The attack began simultaneously with the assault on Pearl Harbor’s naval and air bases in Hawaii on the morning of December 8, 1941 (December 7th in Hawaii) and concluded on December 23rd with the American forces capitulating to the Empire of Japan. The battle took place on the atoll comprising Wake Island and its smaller islets, Peale and Wilkes, involving air, land, and sea forces of the Japanese Empire and the United States, with a notable presence of Marines from both nations. The Japanese forces were formidable, and the majority of the surviving Americans were transported from the island to POW camps by the Japanese. Ninety-seven were left behind to be used as forced labor. The Allies’ response involved intermittent bombing of the island, but no further land invasions occurred. This was in line with a broader Allied strategy to isolate certain Japanese-occupied islands in the South Pacific, effectively leaving them to wither in isolation.

On October 5, 1943, American naval aircraft from the USS Yorktown attacked Wake Island. On October 7, 1943, Rear Admiral Shigematsu Sakaibara, commander of the Japanese garrison on the island, orders the execution of a civilian accused of stealing, and 97 Americans POWs, claiming they were trying to make radio contact with US forces, and a civilian accused of stealing. Initially, the 97 POWs were detained to be used as forced labor. Anticipating an invasion, Sakaibara commanded their execution. They were led to the island’s northern end, blindfolded, and shot with a machine gun. One prisoner, whose name remains unknown, escaped and etched “98 US PW 5-10-43” into a large coral rock near the hastily dug mass grave. This American was later recaptured, and Sakaibara personally beheaded him with a katana. The etched message remains visible, marking a somber landmark on Wake Island to this day. The Wake Island Massacre was an outrage.

The Pacific war finally drew to a close starting in August 1945, and the Emperor of Japan announced the surrender to the Japanese people and the agreement was formally signed by September 2, 1945. On September 4, 1945, the remaining Japanese garrison surrendered to a detachment of United States Marines under the command of Brigadier General Lawson H. M. Sanderson, with the handover being officially conducted in a brief ceremony aboard the destroyer escort USS Levy. Earlier, the garrison received news that Imperial Japan’s defeat was imminent, so the mass grave was quickly exhumed, and the bones were moved to the US cemetery that had been established on Peacock Point after the invasion, with wooden crosses erected in preparation for the expected arrival of US forces. During the initial interrogations, the Japanese claimed that the remaining 98 Americans on the island were mostly killed by an American bombing raid, though some escaped and fought to the death after being cornered on the beach at the north end of Wake Island. Several Japanese officers in American custody committed suicide over the incident, leaving written statements that incriminated Sakaibara. Sakaibara and his subordinate, Lieutenant Commander Tachibana, were later sentenced

to death after conviction for this and other war crimes. Sakaibara was executed by hanging in Guam on June 19, 1947, while Tachibana’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. The remains of the murdered civilians were exhumed and reburied at Section G of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, which is commonly known as Punchbowl Crater, on Honolulu.

to death after conviction for this and other war crimes. Sakaibara was executed by hanging in Guam on June 19, 1947, while Tachibana’s sentence was commuted to life in prison. The remains of the murdered civilians were exhumed and reburied at Section G of the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, which is commonly known as Punchbowl Crater, on Honolulu.

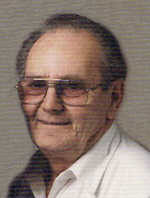

My uncle, Lester “Jim” Wolfe was in the Army during World War II, and as such, was among those who stormed the beaches of Normandy, France on D-Day (June 6, 1944), while my dad, Allen Spencer, his future brother-in-law, was among the B-17s flying cover in the skies above. Thankfully, both of them made it home, and became the men they were destined to be. I really can’t imagine growing up without knowing my Uncle Jim. He was a great guy, with a great sense of humor. He saw a lot of things in his lifetime, and so, he always had great stories to tell. To my child’s mind, my uncle seemed very knowledgeable in things, as did my dad. It was a different era than that of my own, and they knew different things as a result. I guess that is why they always seemed so wise to me.

My uncle, Lester “Jim” Wolfe was in the Army during World War II, and as such, was among those who stormed the beaches of Normandy, France on D-Day (June 6, 1944), while my dad, Allen Spencer, his future brother-in-law, was among the B-17s flying cover in the skies above. Thankfully, both of them made it home, and became the men they were destined to be. I really can’t imagine growing up without knowing my Uncle Jim. He was a great guy, with a great sense of humor. He saw a lot of things in his lifetime, and so, he always had great stories to tell. To my child’s mind, my uncle seemed very knowledgeable in things, as did my dad. It was a different era than that of my own, and they knew different things as a result. I guess that is why they always seemed so wise to me.

While he had a lot of wisdom, Uncle Jim was also a great comedian too. He was always making jokes and loved  to make and hear people laugh. Uncle Jim was a master storyteller, the finest there was. Whenever he began his tales, we’d gather around, eyes wide with amazement. It was always a mystery whether his stories were drawn from life or were pre fiction…until the punchline came. At that moment, we’d burst into laughter, exclaiming, “Oh! Uncle Jim!” He delighted in our reactions, which brought him great amusement. And on the topic of amusement, Uncle Jim was an old hand at tickling. He’d chase and tickle us whenever we pestered him…which, of course, meant we always did. We’d scamper off, trying to escape, though we never really did. Uncle Jim’s heart was as kind as his spirit was playful.

to make and hear people laugh. Uncle Jim was a master storyteller, the finest there was. Whenever he began his tales, we’d gather around, eyes wide with amazement. It was always a mystery whether his stories were drawn from life or were pre fiction…until the punchline came. At that moment, we’d burst into laughter, exclaiming, “Oh! Uncle Jim!” He delighted in our reactions, which brought him great amusement. And on the topic of amusement, Uncle Jim was an old hand at tickling. He’d chase and tickle us whenever we pestered him…which, of course, meant we always did. We’d scamper off, trying to escape, though we never really did. Uncle Jim’s heart was as kind as his spirit was playful.

Uncle Jim was the kind of person who would help anyone in need, whether they were neighbors, friends, or even strangers. His generosity knew no bounds, and he was always ready to offer his assistance. His love for his family was his “above all” priority. He would protect his wife and children at all costs, both in words and actions. He was utterly devoted to them. When he decided to purchase land in Washington to build his final home, he ensured there was enough space for each of his children to have a place of their own nearby. He was determined that none of them would ever be without a home. The property he chose was atop a mountain, offering some of the most stunning views during the ascent. Even in his later years, as Alzheimer’s Disease necessitated his stay in a nursing home, he maintained his happy spirit. He delighted in brightening the day of the nursing staff and

visitors alike, often engaging in harmless “mischief” around the nurses’ station. My sisters and I continue to hold him dear in our hearts. Thoughts of him always bring smiles to our faces. Uncle Jim passed away in 2013, reuniting with his beloved wife, my Aunt Ruth, and other departed family members. We’re comforted by the belief that they’re joyfully together, and we look forward to the day we’ll all be reunited. Today marks what would have been Uncle Jim’s 103rd birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Jim!! We love and miss you very much!!

visitors alike, often engaging in harmless “mischief” around the nurses’ station. My sisters and I continue to hold him dear in our hearts. Thoughts of him always bring smiles to our faces. Uncle Jim passed away in 2013, reuniting with his beloved wife, my Aunt Ruth, and other departed family members. We’re comforted by the belief that they’re joyfully together, and we look forward to the day we’ll all be reunited. Today marks what would have been Uncle Jim’s 103rd birthday. Happy birthday in Heaven, Uncle Jim!! We love and miss you very much!!

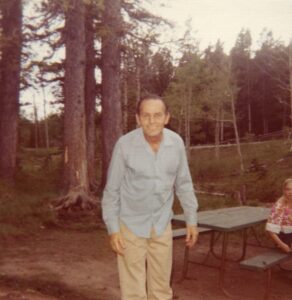

For a number of years, I took my dad, Allen Spencer, who was a top turret gunner and flight engineer on a B-17G during World War II, to see the vintage planes when they came into Casper, Wyoming. Included in those old B-17s was the infamous Nine-O-Nine. Dad loved them all, and it was a special time for us. We crawled through those old planes, and Dad showed me his station, as well as the others on the Flying Fortress. Dad passed away on December 12, 2007, and I think of those special outings every time I see a B-17 flying overhead. The sightings are becoming fewer and further between, sadly. It’s quickly becoming the second end of the World War II era.

For a number of years, I took my dad, Allen Spencer, who was a top turret gunner and flight engineer on a B-17G during World War II, to see the vintage planes when they came into Casper, Wyoming. Included in those old B-17s was the infamous Nine-O-Nine. Dad loved them all, and it was a special time for us. We crawled through those old planes, and Dad showed me his station, as well as the others on the Flying Fortress. Dad passed away on December 12, 2007, and I think of those special outings every time I see a B-17 flying overhead. The sightings are becoming fewer and further between, sadly. It’s quickly becoming the second end of the World War II era.

The Nine-O-Nine was privately owned by the Collings Foundation and on October 2, 2019, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress crashed at Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks, Connecticut. Sadly, seven of the thirteen people on board were killed, and the other six, as well as one person on the ground, were injured. The precious Nine-O-Nine was destroyed by fire, with only a portion of one wing and the tail remaining. I couldn’t believe it when I heard. It was so tragic.

Before the accident, the Collings Foundation operated the aircraft under the Living History Flight Experience, an FAA program permitting vintage military aircraft owners to provide compensated rides. The Foundation’s executive director, Rob Collings, had sought amendments to permit guests to handle the aircraft’s controls, contending that the FAA’s interpretation of the program’s regulations was overly stringent.

The “living history” flight was delayed by 40 minutes due to a problem starting one of the engines. The pilot shut down the other engines and used a spray can to remove moisture before starting the flight. Departing from Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, at 9:48am local time, the aircraft was on a local flight with three crew members and ten passengers. An engine was observed sputtering and emitting smoke. At 9:50am, the pilot reported an issue with the plane’s Number 4 engine, located on the outer right wing. He instructed the crew chief, who also served as the loadmaster, to have the passengers return to their seats. Then, the pilot shut down the Number 4 engine. The control tower cleared the airspace for the aircraft to make an emergency landing on Runway 6. Approaching low, the Nine-O-Nine landed 1,000 feet before the runway, struck the Instrument Landing System (ILS) antenna array, veered right off the runway, crossed a grassy area and a taxiway, and collided with a de-icing facility at 9:54am, bursting into flames. A Connecticut Air National Guardsman, despite sustaining a broken arm and collarbone, successfully opened an escape hatch following the plane crash. Meanwhile, an airport worker, who was in the building struck by the plane, rushed to the crash site to assist in extracting injured passengers from the fiery wreckage. This individual incurred serious burns to his hands and arms and was subsequently transported to the hospital by ambulance. The pilot and co-pilot, aged 75 and 71, were among the seven fatalities. Additionally, one individual on the ground sustained injuries. The airport remained closed for three and a half hours after the incident.

According to the final report released by the NTSB on May 17, 2021, the probable cause of the crash was: “The pilot’s failure to properly manage the airplane’s configuration and airspeed after he shut down the Number 4 engine following its partial loss of power during the initial climb. Contributing to the accident was the inadequate

maintenance of the airplane while it was on tour, which resulted in the partial loss of power to the Numbers 3 and 4 engines; the ineffective safety management system (SMS) of the Collings Foundation, which failed to identify and mitigate safety risks; and the FAA’s inadequate oversight of the Collings Foundation’s SMS.”

maintenance of the airplane while it was on tour, which resulted in the partial loss of power to the Numbers 3 and 4 engines; the ineffective safety management system (SMS) of the Collings Foundation, which failed to identify and mitigate safety risks; and the FAA’s inadequate oversight of the Collings Foundation’s SMS.”

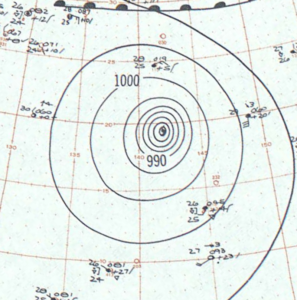

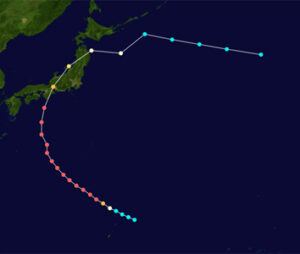

Typhoon Vera, also known as the Isewan Typhoon, was an extraordinarily powerful tropical cyclone that hit Japan in September 1959. It became the most intense and deadliest typhoon to ever make landfall in the country, and it remains the only one to have done so as a Category 5 equivalent storm. The typhoon caused unprecedented catastrophic damage, severely impacting the Japanese economy, which was in the midst of post-World War II recovery. Following Vera, Japan underwent significant reforms in disaster management and relief operations, establishing a new standard for handling future storms. The country is still well known for its disaster preparedness.

Typhoon Vera, also known as the Isewan Typhoon, was an extraordinarily powerful tropical cyclone that hit Japan in September 1959. It became the most intense and deadliest typhoon to ever make landfall in the country, and it remains the only one to have done so as a Category 5 equivalent storm. The typhoon caused unprecedented catastrophic damage, severely impacting the Japanese economy, which was in the midst of post-World War II recovery. Following Vera, Japan underwent significant reforms in disaster management and relief operations, establishing a new standard for handling future storms. The country is still well known for its disaster preparedness.

Typhoon Vera formed on September 20 between Guam and Chuuk State, initially moving westward before shifting to a northerly path and reaching tropical storm status the next day. The storm then took a turned westward, rapidly intensifying to peak intensity on September 23 with maximum sustained winds that made it Category 5 hurricane. Maintaining its strength, Vera veered northward and made landfall near Shionomisaki on Honshu on September 26. Influenced by atmospheric winds, the typhoon briefly entered the Sea of Japan, then recurved eastward, making a second landfall on Honshu. Crossing over land significantly weakened Vera, and

upon reentering the North Pacific Ocean that same day, it became an extratropical cyclone on September 27, with its remnants lasting two more days.

upon reentering the North Pacific Ocean that same day, it became an extratropical cyclone on September 27, with its remnants lasting two more days.

Although Vera’s path into Japan was accurately predicted, the limited telecommunications coverage, combined with the Japanese media’s lack of urgency and the storm’s severity, significantly hindered evacuation and disaster prevention efforts. The flooding from the storm’s peripheral rainbands started affecting river basins before the typhoon made landfall. As it hit Honshu, Vera unleashed a powerful storm surge, destroying many flood defenses, flooding coastal areas, and causing ships to sink. Vera resulted in damages totaling $600 million US dollars, which was equivalent to $6.27 billion US dollars in 2023. The death toll from Vera is uncertain, but current figures suggest the typhoon caused over 5,000 deaths, ranking it among the most lethal typhoons in Japan’s history. Additionally, it injured nearly 39,000 individuals and also displaced around 1.6 million people.

Immediately after Typhoon Vera, the Japanese and American governments launched relief operations. The typhoon’s flooding led to localized outbreaks of diseases such as dysentery and tetanus. These epidemics, along

with obstructive debris, hindered the relief process. In response to the extensive damage and casualties caused by Vera, the National Diet, which is the national legislature of Japan, enacted laws to better support the impacted areas and reduce the impact of future disasters. This led to the creation of the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act in 1961, which laid down guidelines for disaster response in Japan, including forming the Central Disaster Prevention Council.

with obstructive debris, hindered the relief process. In response to the extensive damage and casualties caused by Vera, the National Diet, which is the national legislature of Japan, enacted laws to better support the impacted areas and reduce the impact of future disasters. This led to the creation of the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act in 1961, which laid down guidelines for disaster response in Japan, including forming the Central Disaster Prevention Council.

Very often, those we would least expect to rise to greatness, show us just how wrong we were. Grace Murray Hopper, at a very young age showed an interest in engineering. She could often be found taking household goods apart. Still, lots of kids have taken things apart, but then Grace would put them back together too. Still, her family had no idea that her curiosity would eventually gain her recognition from the highest office in the land. She was just a curious kid…right? Well, maybe not.

Very often, those we would least expect to rise to greatness, show us just how wrong we were. Grace Murray Hopper, at a very young age showed an interest in engineering. She could often be found taking household goods apart. Still, lots of kids have taken things apart, but then Grace would put them back together too. Still, her family had no idea that her curiosity would eventually gain her recognition from the highest office in the land. She was just a curious kid…right? Well, maybe not.

Hopper was born in New York City on December 9, 1906. She started out in the normal educational way, attending a preparatory school in New Jersey. Then after her high school education ended, she began her journey to greatness. She enrolled at Vassar College. After graduating with her Bachelor’s degree, Hopper went to Yale University, where she earned her Master’s degree and PhD in Mathematics. The she went on to teach at Vassar College.

So, in 1943, Hopper resigned her position at Vassar to join the Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service). She felt a higher calling. In 1944, she was commissioned as a Lieutenant (Junior Grade) and assigned to the Bureau of Ordnance Computation Project at Harvard University. She was on her way to that greatness. Her team worked on and produced an early prototype of the electronic computer, called the Mark I. She also wrote a 500-page Manual of Operations for the Automatic Sequence-Controlled Calculator, outlining the fundamental operating principles of computing machines. It was also Hopper that came up with the term “bug” to describe a computer malfunction. We all know that term these days.

When World War II was over Hopper went on to become a research fellow on the Harvard faculty, and in 1949,  she joined the Eckert-Mauchly Corporation, so she could continue her pioneering work on computer technology. When you see things like UNIVAC, the first all-electronic digital computer, think of Hopper. She also invented the first computer compiler, a program that translates written instructions into codes that computers read directly. The work she did on the compiler led her to co-develop the COBOL, which was one of the earliest standardized computer languages. COBOL allows computers to respond to words in addition to numbers. It was an important step into a new era. Along with her work on computers and technical innovation, Hopper also lectured widely on computers, giving up to 300 lectures per year. She saw a world where computers were mainstream. In fact, she predicted that computers would one day be small enough to fit on a desk and people who were not professional programmers would use them in their everyday life. As we all know, that is exactly what has come to pass.

she joined the Eckert-Mauchly Corporation, so she could continue her pioneering work on computer technology. When you see things like UNIVAC, the first all-electronic digital computer, think of Hopper. She also invented the first computer compiler, a program that translates written instructions into codes that computers read directly. The work she did on the compiler led her to co-develop the COBOL, which was one of the earliest standardized computer languages. COBOL allows computers to respond to words in addition to numbers. It was an important step into a new era. Along with her work on computers and technical innovation, Hopper also lectured widely on computers, giving up to 300 lectures per year. She saw a world where computers were mainstream. In fact, she predicted that computers would one day be small enough to fit on a desk and people who were not professional programmers would use them in their everyday life. As we all know, that is exactly what has come to pass.

While her time of active service to her country was behind her, Hopper retained her affiliation with the Naval Reserve throughout her latter career. Moving up, she attained the rank of Commander by 1966. Then, as happens in the reserves sometimes, Hopper was called back to active duty in 1967. She was assigned to the Chief of Naval Operations’ staff as Director of the Navy Programming Languages Group. Hopper continued to move up the ranks, reaching the rank of Captain in 1973, Commodore in 1983, and Rear Admiral in 1985. She  basically had two great careers. In 1987, she was awarded the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, the highest decoration given to those who did not participate in combat. It was a moment to be very proud of.

basically had two great careers. In 1987, she was awarded the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, the highest decoration given to those who did not participate in combat. It was a moment to be very proud of.

While her military career had been amazing, her work with computers wasn’t anything to make light of either. She not only gained national attention, but she was recognized internationally for her work with computers. In 1973, Hopper was named a distinguished fellow of the British Computer Society. At that time, she was the first and only woman to hold the title. Hopper retired, but she couldn’t really retire, so she returned to the classroom, where she taught and inspired students until her death on January 1st, 1992. Throughout her life, Hopper had many career accomplishments, but she later said that her greatest joy came from teaching. In 2016, Hopper was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Her body is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

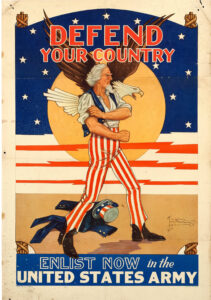

As is expected in a world war, many soldiers are needed. So, the World War II army of the US became the biggest army in history. Citizens of the United States are notorious for patriotism, when we have been attacked. It is like waking a sleeping giant, and we will retaliate with a vengeance. Due in part to that surge of American patriotism and also because of conscription (the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service,

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

In order to determine which of the armies were the largest in history, 24/7 Wall Street reviewed a list of military superpowers from Business Insider. These armies were ranked based on the total number of troops that were serving a country or empire at the point when the army was at its largest. Without doubt, the United States was, and remains to this day, the nation with the largest army in history. Over the years, the armed forces of the United States have been larger and smaller, depending on the need at the time, the administration

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

Even before the first airplane too flight, there were people who wanted to be airborne. Human flight first became a reality in the early 1780s with the successful development of the hot-air balloon by French papermaking brothers Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier. Soon balloons were being filled with lighter-than-air gas, such as helium or hydrogen, to provide buoyancy. It was a whole new era. Finally, on November 21, 1783, the first manned hot air balloon took flight. Man could be airborne and come back to earth safely. With that, came the natural desire to try to go higher and further. Man was not done with flight, and in fact this was just the beginning.

Even before the first airplane too flight, there were people who wanted to be airborne. Human flight first became a reality in the early 1780s with the successful development of the hot-air balloon by French papermaking brothers Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier. Soon balloons were being filled with lighter-than-air gas, such as helium or hydrogen, to provide buoyancy. It was a whole new era. Finally, on November 21, 1783, the first manned hot air balloon took flight. Man could be airborne and come back to earth safely. With that, came the natural desire to try to go higher and further. Man was not done with flight, and in fact this was just the beginning.

An early achievement of ballooning came in 1785 when Frenchman Jean-Pierre Blanchard and American John Jeffries became the first to cross the English Channel by air. While early manned flight did occur, it wasn’t the normal mode of transportation. In the 18th and 19th centuries, balloons were used more for military surveillance and scientific study than for transport or sport. As a mode of air travel, the balloon was replaced by the self-propelled dirigible, which was a motorized balloon, in the late 19th century.

While balloons were used for military purposes early on, by the early 20th century, interest in sport ballooning began to grow. Then, the inevitable was offered…an international trophy, to be offered annually for long- distance flights. Belgian balloonists were the dominate winners of these early competitions, but after World War II, new technology began to emerge, making ballooning safer and more affordable, By the 1960s hot air ballooning enjoyed widespread popularity. There were 17 unsuccessful transatlantic balloon flights from 1859 until the flight of the Double Eagle II in 1978. These resulted in the deaths of at least seven balloonists. One of the unsuccessful flights was in September 1977, when Ben Abruzzo and Maxie Anderson made their first attempt in the Double Eagle I. They were blown off course and forced to ditch off Iceland after traveling 2,950 miles in 66 hours. It was a brutal wait for rescue, and Abruzzo took several months to recover from frostbite that he suffered during the ordeal. Then, by 1978 he and Anderson were ready to try again. With the addition of Larry Newman as a third pilot. The men took off on September 11, 1978, in the Double Eagle II. The flight lifted off from Presque Isle, Maine.

distance flights. Belgian balloonists were the dominate winners of these early competitions, but after World War II, new technology began to emerge, making ballooning safer and more affordable, By the 1960s hot air ballooning enjoyed widespread popularity. There were 17 unsuccessful transatlantic balloon flights from 1859 until the flight of the Double Eagle II in 1978. These resulted in the deaths of at least seven balloonists. One of the unsuccessful flights was in September 1977, when Ben Abruzzo and Maxie Anderson made their first attempt in the Double Eagle I. They were blown off course and forced to ditch off Iceland after traveling 2,950 miles in 66 hours. It was a brutal wait for rescue, and Abruzzo took several months to recover from frostbite that he suffered during the ordeal. Then, by 1978 he and Anderson were ready to try again. With the addition of Larry Newman as a third pilot. The men took off on September 11, 1978, in the Double Eagle II. The flight lifted off from Presque Isle, Maine.

The 11-story, helium-filled balloon made good progress during the first four days, and the three pilots survived on hot dogs and canned sardines. Things seemed to be going perfectly this time. The only real trouble of the trip occurred on August 16, when atmospheric conditions forced the Double Eagle II to drop from 20,000 feet to a dangerous 4,000 feet. To ward off trouble, they jettisoned ballast material and rose to a safe height again. With the added altitude, they reached the coast of Ireland and on August 17 flew across England en route to their destination of Le Bourget field in Paris, which was the site of Charles Lindbergh’s landing after flying solo in a plane across the Atlantic in 1927. In a touching moment, their wives flew close enough to the balloon in a private plane as it traveled over England, to blow kisses at their husbands.

Double Eagle II was blown slightly off course toward the end of the journey, and they actually touched down just before dusk on August 17th, near the hamlet of Miserey, about 50 miles west of Paris. Their 137-hour flight set new endurance and distance records. The Americans were greeted by family members and jubilant French spectators who followed their balloon by car. That night, Larry Newman, who at 31 was the youngest of the three pilots, was allowed to sleep with his wife in the same bed where Charles Lindbergh slept after his historic transatlantic flight five decades before. Transatlantic balloon flight had finally been realized.

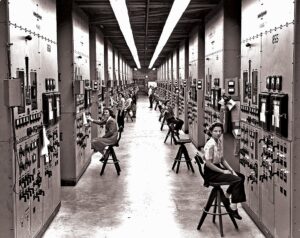

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

During World War II, a group of young women, mostly high school graduates, joined the Manhattan Project at the Y-12 National Security Complex located at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Known as the Calutron Girls, the group worked for the project from 1943 to 1945. The women were taught to monitor dials and watch meters for calutrons, which are mass spectrometers adapted for separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons for use during World War II. While the women worked at their jobs, and learned how to read the instruments they were required to monitor, they were not allowed to know the purpose of these things.

They were actually monitoring the manufacturing of enriched uranium that was to be used to make the “Little Boy” atomic bomb for the Hiroshima nuclear bombing to be carried out on August 6, 1945. The Manhattan Project, which was established to develop nuclear weapons, required uranium-235 (U235), the fissionable isotope of uranium. The vast majority of uranium that is mined from the ground is uranium-238. Only about while only 0.7% is U235. The scientists in charge of the project developed several processes for separating the isotopes of uranium, including electromagnetic separation and gaseous diffusion.

“The Y-12 factory was built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to house 1,152 calutrons, a machine used for isotope separation. The word “calutron” is a portmanteau of California University Cyclotron. Calutrons, a variation on mass spectrometers, work by combining uranium with chlorine to make uranium tetrachloride, which is then ionized and put in a vacuum chamber with a magnetic field. When the charged particles move through the magnetic field, they move in a curve, the radius of which is proportional to the mass of the particles. The two isotopes differ in mass by about 1% and can thus be separated.”

The process of separating the U235 Uranium out of the oar was relatively simple, but it still required people to constantly monitor the calutrons. Unfortunately, during World War II, many of the men were fighting. That left a shortage of labor. There simply weren’t enough scientists to operate all of the calutrons. So, the government recruited farm girls to operate the calutrons instead. The main reason for using the young women, was that they were readily available, accustomed to hard work. A stipulation of their employment was that they were not to ask excessive questions, and they had to be loyal and docile. I’m sure these women thought they were doing something top secret and all, but I don’t think they had any idea of the gravity of this project. Lives were on the line, and lives would be lost. Still, they didn’t know that, so I suppose their superiors assumed it would let them sleep at night. I suppose it did. These women honestly didn’t know what they were a part of…some until years later. They would never forget what they did, and they would always wonder if it was right or wrong.

The Tennessee Eastman Company, which ran the Y-12 site, recruited around 10,000 local women between 1943 and 1945. They hired train operators with only a high school education, and they used a large local advertising campaign to recruit workers. One ad read, “When you’re a grandmother you’ll brag about working at Tennessee Eastman.” Word of mouth brought in several other workers. Of course, in hard times, a big motivator was the money being paid. Plus, these women were patriots, and this work was for the war effort. They were trained for three weeks, and they went to work.

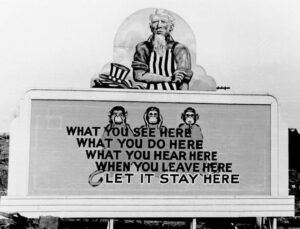

The Tennessee Eastman Company was loyal to the cause. They put a billboard on the premises reading “What you see here / what you do here / what you hear here / when you leave here / let it stay here,” with three wise monkeys to demonstrate “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” Another billboard at the Oak Ridge location,  encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

encouraged secrecy among workers. These companies demanded secrecy and confidentiality…if these women wanted to keep their jobs. According to Gladys Owens, who was one of the Calutron Girls, a manager at the facility once told them, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!” Of course, that was correct, but these women would have to live with what they did, once they knew what it was. Testimonies said women who talked about what they were doing disappeared. One young woman who “disappeared” was said to have “died from drinking some poison moonshine.” If they were too nosy about what they were working on, they were replaced. Cars going in and out were searched, and letters were opened and read. This was vital and this was no joke. Anything but secrecy would not be tolerated.

The work these women did was not what would be considered labor intensive by any means. The women sat on high stools for 8-hour shifts, seven days per week, “monitoring gauges and adjusting knobs to keep the needles where they were supposed to be and recording readings.” The knobs the women were adjusting were simply labeled with cryptic letters. The women did not know what the letters stood for. What they were taught was that “if you got your M voltage up and your G voltage up, then Product would hit the birdcage in the E box at the top of the unit and if that happened, you’d get the Q and R you wanted.” Okay…whatever that meant. All they knew was that they had to make sure the machine remained at the correct temperature. That was vital and if it got too hot, they used liquid nitrogen to cool it down. If the needles reached a point where they could not control them, they had to call someone else to come help…immediately!!!

Former Calutron Girl Wynona Arrington Butner said, “We all wore little fountain-pen-sized dosimeters. Part of signing out of the plant was to check the amount of radiation that you had absorbed every day.” Civilian workers paid $2.50 per month (single) or $5.00 per month (family) for medical insurance. I don’t know if they understood what radiation could do to them or not, but if they did, they would know that the wages paid and even the insurance help, was probably not enough.

Some Calutron Girls had more of a sense of what they were working on than others. Butner, who had some training in chemistry, said she and others with a similar background had some sense of what they were doing. They knew they were producing “the Product,” and they guessed it was somewhere near the bottom of the periodic table. Willie Baker, on the other hand, said, “Even when somebody let it slip that we were building a bomb, I didn’t know what they meant. I was just a country girl. I had no understanding of what an atomic bomb was.” Later, I’m sure the gravity of the work she did, weighed heavily on Baker.

Over two years, the calutrons at Y-12 had produced about 140 pounds of U235. This was enough to make the first atomic bomb. By December 1945, enough uranium for a second Little Boy was available. Then, it all hit these women, because on August 6, 1945, when the US dropped the first bomb, “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima, Japan, the Calutron Girls were finally told what they had been working on. I can’t imagine how they must have felt. When they heard the news, some women were working, while others were in their dorm rooms. Someone came and told them that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan, and everyone there had played a part in making it. Yes, it was the enemy, and death happens in war. Nevertheless, the Calutron Girls had mixed feelings about their part in the bomb. Ruth Huddleston said she was “really happy at the time, because her boyfriend was stationed in Germany, and this would bring him back.” Still, it bothered her that she had a part in killing so many people, but she accepted that “if the bomb hadn’t been dropped, then probably more people would have been killed. …But even today, if I think too much about it, it bothers me.” Butner had a similar experience, because at the time, she was happy that the war was over and people she knew in the service could come  home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

home, but over time, she began to question whether it was the right thing to do. I think many people over the years have questioned it, but good, bad, or ugly, World War II was over.

Most of the Calutron Girls are gone now, but those who remain, such as Huddleston, regularly shared their stories with the public, often alongside Oak Ridge historian Ray Smith. The women are the subject of the nonfiction book “The Girls of Atomic City” by Denise Kiernan and the novel “The Atomic City Girls” by Janet Beard. I’m sure that many of these women suffered nightmares over the work they did, but did not know they were doing. While I know they suffered much anxiety over that, I hope they also know that we are so grateful for their service to this great nation.

My nephew, Chris Killinger joined our family when he married my niece, Lacey (Stevens) Killinger a little under a year ago. Chris and Lacey are such a beautiful couple, and their wedding was just lovely. Since then, they have just been enjoying married life, and spending time with the kids, Brooklyn and Jaxon, who also joined our family with Chris married Lacey. They have all been a wonderful addition to our family.

My nephew, Chris Killinger joined our family when he married my niece, Lacey (Stevens) Killinger a little under a year ago. Chris and Lacey are such a beautiful couple, and their wedding was just lovely. Since then, they have just been enjoying married life, and spending time with the kids, Brooklyn and Jaxon, who also joined our family with Chris married Lacey. They have all been a wonderful addition to our family.

Chris and Lacey didn’t take a honeymoon right away, but later went to Mexico, and they had a super fun time. Chris and Lacey both have very demanding jobs, and they were ready for some down time. One of the highlights of the trip was when they went swimming in caves down there. The cave walls were beautiful, and it was a very different experience for them. The trip was one they won’t forget.

Chris is the office and purchasing manager for Atlas Aero Service, which is located at the Casper-Natrona  County International Airport. Chris’ job allows him to see all the planes that come and go from the airport. There is a huge variety of planes…military planes, cargo planes, commercial liners, and private jets (often with celebrities). Recently, however, the celebrity wasn’t the person on the plane…it was the plane. Chris knows planes, and he likes planes. He has a real interest in military planes. The plane that they got to work on recently was a plane that had been used in the movie “Tora, Tora, Tora” back in the 1970s. The movie was about the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and while I know that Chris though it was very cool to work on that plane, I can’t help but think about how interested my dad, Al Spencer, Lacey’s grandpa would have loved to see that plane. He was the flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-17 during World War II, so that plane would have been so cool for him to see. I’m glad Chris got that chance…such a cool experience, and one he will never forget for sure.

County International Airport. Chris’ job allows him to see all the planes that come and go from the airport. There is a huge variety of planes…military planes, cargo planes, commercial liners, and private jets (often with celebrities). Recently, however, the celebrity wasn’t the person on the plane…it was the plane. Chris knows planes, and he likes planes. He has a real interest in military planes. The plane that they got to work on recently was a plane that had been used in the movie “Tora, Tora, Tora” back in the 1970s. The movie was about the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, and while I know that Chris though it was very cool to work on that plane, I can’t help but think about how interested my dad, Al Spencer, Lacey’s grandpa would have loved to see that plane. He was the flight engineer and top turret gunner on a B-17 during World War II, so that plane would have been so cool for him to see. I’m glad Chris got that chance…such a cool experience, and one he will never forget for sure.

Recently, Chris and Lacey bought a new camper, and they have been having a great time with it. Chris has had

to learn how to pull it, which isn’t easy, but he is getting the hang of it. They have been having a great time going camping and they love their new camper. Lacey’s family takes yearly trips to Pathfinder Reservoir for a whole family week of fun, swimming, games, and lounging. Having a nice camper with room for their whole family is very important. The camper will get lots of use. Today is Chris’ birthday. Happy birthday Chris!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

to learn how to pull it, which isn’t easy, but he is getting the hang of it. They have been having a great time going camping and they love their new camper. Lacey’s family takes yearly trips to Pathfinder Reservoir for a whole family week of fun, swimming, games, and lounging. Having a nice camper with room for their whole family is very important. The camper will get lots of use. Today is Chris’ birthday. Happy birthday Chris!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

In June of 1942, Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping, a 24-year-old British pilot, who was part of the 260 Squadron of the RAF Volunteer Reserves was tasked with flying P-40 Kittyhawk (serial code ET574), on a ferry flight to a neighboring British airbase to have the undercarriage repaired. The upcoming Summer Offensive that year, was to include the P-40s. Copping took off on June 28 and headed West. He was never seen again, even with extensive searches being undertaken. Both the aircraft and its pilot were reported missing. After a time, the search was called off, because they couldn’t find anything.

In June of 1942, Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping, a 24-year-old British pilot, who was part of the 260 Squadron of the RAF Volunteer Reserves was tasked with flying P-40 Kittyhawk (serial code ET574), on a ferry flight to a neighboring British airbase to have the undercarriage repaired. The upcoming Summer Offensive that year, was to include the P-40s. Copping took off on June 28 and headed West. He was never seen again, even with extensive searches being undertaken. Both the aircraft and its pilot were reported missing. After a time, the search was called off, because they couldn’t find anything.

The lost flight stayed a mystery for almost 70 years. Then, in April 2012, workers of a Polish Oil company discovered the remarkably well-preserved remains of a P-40. It’s quite likely that they not only had no idea how it could have come to be there, nor when. Nevertheless, the desert’s extremely dry conditions had basically ‘mummified” the P-40, as it only showed minimal rust and decay.

The wings of the P-40 were half-buried under the sand, but they were still in very good condition, with the exception of the fact that the fabric-covered control surfaces had rotten away. Even the cockpit was still somewhat preserved, and the aircraft still had live ammunition loaded in the magazines of its six machine guns.

When the authorities were called in, they were easily able to link the downed P-40 Kittyhawk to Dennis  Copping, because of its relatively good condition. They finally knew what had happened to Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping and his Kittyhawk exactly 69 years, 9 months, and 14 days later. The only thing missing was the pilot. It was then assumed that Copping had survived the crash, but where was he? The only thing they could assume was that he must have tried to walk out. The problem is that Copping was lost and alone in the middle of the largest desert on Earth. They began the search again, but this time with the plane as a starting point.

Copping, because of its relatively good condition. They finally knew what had happened to Flight Sergeant Dennis Copping and his Kittyhawk exactly 69 years, 9 months, and 14 days later. The only thing missing was the pilot. It was then assumed that Copping had survived the crash, but where was he? The only thing they could assume was that he must have tried to walk out. The problem is that Copping was lost and alone in the middle of the largest desert on Earth. They began the search again, but this time with the plane as a starting point.

They found a small makeshift camp built next to the aircraft. Near it was the plane’s battery and radio. This meant that Copping probably attempted to broadcast for help. Unfortunately, the radio, or at least the internal workings of it had been destroyed by the crash landing. Finally, unable to call for help, Copping knew he would have to leave the plane and go for help. The teams continued their search, and a group of Italian historians uncovered a number of human bones five kilometers from the crash site. However, it was decided that those bones probably “did not belong” to Copping as they were “too old” to be his. Interestingly, the bones were never tested for any DNA. The historians were also able to find a section of the parachute, a keyfob, and a buckle stamped ‘1939,’ which were things Copping might have had with him at the time of his death.

Because of the desert’s dry conditions, the ET574 Kittyhawk was able to be fully restored. Of course, given the

years and the fact that it was a crash, the restoration is far from perfect. and it sports a historically inaccurate camouflage scheme. Maybe someday, it will be restored to a historically accurate condition. Nevertheless, it is the last surviving example of a Desert Air Force P-40 Kittyhawk in existence. The mystery was finally solved.

years and the fact that it was a crash, the restoration is far from perfect. and it sports a historically inaccurate camouflage scheme. Maybe someday, it will be restored to a historically accurate condition. Nevertheless, it is the last surviving example of a Desert Air Force P-40 Kittyhawk in existence. The mystery was finally solved.