war of 1812

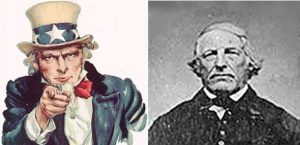

Everyone has heard the term, Uncle Sam used when referring to the United States government, but while the government and the people of the United States have “adopted” that term to mean the United States government, it was really never intended to be so. If you ask most people, the average older American would most likely point to the early 20th century and Sam’s frequent appearance on army recruitment posters. Nevertheless, the figure of Uncle Sam actually dates back much further than that. The actual figure of Uncle Sam, dates from the War of 1812. At that point, most American icons had been geographically specific, centering most often on the New England area. However, the War of 1812 sparked a renewed interest in national identity which had faded since the American Revolution.

Everyone has heard the term, Uncle Sam used when referring to the United States government, but while the government and the people of the United States have “adopted” that term to mean the United States government, it was really never intended to be so. If you ask most people, the average older American would most likely point to the early 20th century and Sam’s frequent appearance on army recruitment posters. Nevertheless, the figure of Uncle Sam actually dates back much further than that. The actual figure of Uncle Sam, dates from the War of 1812. At that point, most American icons had been geographically specific, centering most often on the New England area. However, the War of 1812 sparked a renewed interest in national identity which had faded since the American Revolution.

The term Uncle Sam was actually the nickname of a man named Samuel Wilson, who was a meat packer from Troy, New York. Sam supplied rations for the soldiers during the War of 1812. He had served in the American Revolution at the age of 15, and while he was born in Massachusetts, he relocated to the town of Troy, New York after the war. In Troy, Samuel and his brother, Ebenezer began the firm of E and S Wilson, a meat packing facility. Samuel was a man of great fairness, reliability, and honesty, who was devoted to his country. All of the local residents really liked Samuel, and they began calling him Uncle Sam.

During the War of 1812, the demand for meat supply for the troops was badly needed. Because he had been a soldier, Samuel had a soft spot in his heart for the soldiers. Secretary of War, William Eustis, made a contract with Elbert Anderson Jr of New York City to supply and issue all rations necessary for the United States forces in New York and New Jersey for one year. Anderson ran an advertisement on October 6, 1813 looking to fill the contract. The Wilson brothers bid for the contract and won. The contract was to fill 2,000 barrels of pork and 3,000 barrels of beef for one year. Their location on the Hudson River, made it ideal to receive the animals and to ship the product. As a security measure, the contractors were required to stamp their name and where the rations came from onto the food they were sending. Wilson’s packages bore the label “E.A. – US,” which stood for Elbert Anderson, the contractor, and the United States. When an individual in the meat packing facility asked what it stood for, a coworker joked and said it referred to Sam Wilson, Uncle Sam. A number of the soldiers were originally from Troy, and familiar with Samuel. When they saw the designation on the barrels, they, being acquainted with Sam Wilson and his nickname Uncle Sam, as well as the knowledge that Wilson was feeding the army, led them to the same conclusion. The local newspaper soon picked up on the story and Uncle Sam eventually gained widespread acceptance as the nickname for the U.S. federal government.

This is, of course, an endearing local story, and therefore, leaves some doubt as to whether it is the actual source of the term. Uncle Sam is mentioned previous to the War of 1812 in the popular song “Yankee Doodle,” which appeared in 1775. Nevertheless, the song doesn’t make it clear whether this reference is to Uncle Sam as a metaphor for the United States, or to an actual person named Sam. Another early reference to the term appeared in 1819, predating Wilson’s contract with the government. The connection between this local saying and the national legend is not easily traced. As early as 1830, there were inquiries into the origin of the term Uncle Sam. The connection between the popular cartoon figure and Samuel Wilson was reported in the New York Gazette on May 12, 1830. Whatever the source, Uncle Sam immediately became popular as a symbol of an ever-changing nation. His “likeness” appeared in drawings in various forms including resemblances to Brother Jonathan, a national personification and emblem of New England, and Abraham Lincoln, and others. In the late 1860s and 1870s, a political cartoonist named Thomas Nast began popularizing the image of Uncle Sam…building on the warm fuzzy feel of a beloved uncle. Nast continued to evolve the image, eventually giving Sam the white beard and stars-and-stripes suit that are associated with the character today.

However, it was a military recruiting poster, created in about 1917, that set the image of Uncle Sam was firmly set into American consciousness. The famous “I Want You” recruiting poster was created by James Montgomery Flagg and four million posters were printed between 1917 and 1918. The image was a really powerful one:  Uncle Sam’s striking features, expressive eyebrows, pointed finger, and direct address to the viewer made this drawing into an American icon. Throughout the years, Uncle Sam has appeared in advertising and on products ranging from cereal to coffee to car insurance. His likeness also continued to appear on military recruiting posters and in numerous political cartoons in newspapers. Finally, in September of 1961, the U.S. Congress recognized Samuel Wilson as “the progenitor of America’s national symbol of Uncle Sam.” Samuel Wilson died at age 88 in 1854, and was buried next to his wife Betsey Mann in the Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, New York. The town proudly calls itself “The Home of Uncle Sam.”

Uncle Sam’s striking features, expressive eyebrows, pointed finger, and direct address to the viewer made this drawing into an American icon. Throughout the years, Uncle Sam has appeared in advertising and on products ranging from cereal to coffee to car insurance. His likeness also continued to appear on military recruiting posters and in numerous political cartoons in newspapers. Finally, in September of 1961, the U.S. Congress recognized Samuel Wilson as “the progenitor of America’s national symbol of Uncle Sam.” Samuel Wilson died at age 88 in 1854, and was buried next to his wife Betsey Mann in the Oakwood Cemetery in Troy, New York. The town proudly calls itself “The Home of Uncle Sam.”

Captain George Hollins joined the United States Navy when he was just 15 years old, and served during the War of 1812. His was a long and distinguished career, but when the Civil War broke out in 1861, he chose to resign his commission, and offer his services to the Confederacy. After a brief stop in his hometown, Baltimore, Hollins offered his services to the Confederacy and received a commission on June 21, 1861. I suppose that every man had to choose a side in the Civil War, and I’m sure he considered his reasons for choosing the Confederacy to be valid, but many of us would consider his actions to be almost traitorous, were it not for the fact that both sides were the United States…just not so united.

Captain George Hollins joined the United States Navy when he was just 15 years old, and served during the War of 1812. His was a long and distinguished career, but when the Civil War broke out in 1861, he chose to resign his commission, and offer his services to the Confederacy. After a brief stop in his hometown, Baltimore, Hollins offered his services to the Confederacy and received a commission on June 21, 1861. I suppose that every man had to choose a side in the Civil War, and I’m sure he considered his reasons for choosing the Confederacy to be valid, but many of us would consider his actions to be almost traitorous, were it not for the fact that both sides were the United States…just not so united.

Hollins devised a plan to capture a commercial vessel that was bringing supplies to the Union Army. Then they planned to use that ship to lure other Union ships into Confederate service. Soon after, Hollins met up with Richard Thomas Zarvona, a fellow Marylander and former student at West Point. Zarvona  was an adventurer who had fought with pirates in China and revolutionaries in Italy. He seemed the perfect co-conspirator for this project. They devised a plan to capture the Saint Nicholas. Then it would be the decoy they used to force other Yankee ships into Confederate service. Zarvona went to Baltimore,where he recruited a band of pirates, who boarded the Saint Nicholas as paying passengers on June 28, 1862. Using the name Madame La Force, Zarvona disguised himself as a flirtatious French woman. Hollins boarded the Saint Nicholas at its first stop.

was an adventurer who had fought with pirates in China and revolutionaries in Italy. He seemed the perfect co-conspirator for this project. They devised a plan to capture the Saint Nicholas. Then it would be the decoy they used to force other Yankee ships into Confederate service. Zarvona went to Baltimore,where he recruited a band of pirates, who boarded the Saint Nicholas as paying passengers on June 28, 1862. Using the name Madame La Force, Zarvona disguised himself as a flirtatious French woman. Hollins boarded the Saint Nicholas at its first stop.

A while later the band of co-conspirators went to the “French woman’s” cabin. Inside, they armed themselves and came back out on the deck to surprise the crew. After  capturing the crew, Hollins took control of the ship. At this point, the purpose of their mission began. They had planned to capture a Union gunboat, the Pawnee, but it was called away. Instead, the Saint Nicholas and its pirate crew came upon a ship loaded with Brazilian coffee, and two more ships, carrying loads of ice and coal. Both ships quickly fell to the Saint Nicholas. For his actions, Hollins received a promotion to commodore and was sent to New Orleans to command the naval forces there at the end of July. On July 8, he would try another daring mission, to capture the Columbia, a sister ship of the Saint Nicholas, but the captain of the Saint Nicholas was on board the Columbia, on his way home after being released by the Confederate authorities. He recognized the men and they were arrested. It was the end of his tirade.

capturing the crew, Hollins took control of the ship. At this point, the purpose of their mission began. They had planned to capture a Union gunboat, the Pawnee, but it was called away. Instead, the Saint Nicholas and its pirate crew came upon a ship loaded with Brazilian coffee, and two more ships, carrying loads of ice and coal. Both ships quickly fell to the Saint Nicholas. For his actions, Hollins received a promotion to commodore and was sent to New Orleans to command the naval forces there at the end of July. On July 8, he would try another daring mission, to capture the Columbia, a sister ship of the Saint Nicholas, but the captain of the Saint Nicholas was on board the Columbia, on his way home after being released by the Confederate authorities. He recognized the men and they were arrested. It was the end of his tirade.

Part of the War of 1812 involved a border dispute between the United States and British North America, which is present-day Canada. During the war, the Americans launched several invasions into Upper Canada, at the point of present-day Ontario. One section of the border where this was easiest, because of communications and locally available supplies, was along the Niagara River. Fort Erie was the British post at the head of the river, near its source in Lake Erie. In 1812, two American attempts to capture Fort Erie were bungled by Brigadier General Alexander Smyth. Bad weather or poor administration halted the American efforts to cross the river, and Fort Erie remained in British hands.

Part of the War of 1812 involved a border dispute between the United States and British North America, which is present-day Canada. During the war, the Americans launched several invasions into Upper Canada, at the point of present-day Ontario. One section of the border where this was easiest, because of communications and locally available supplies, was along the Niagara River. Fort Erie was the British post at the head of the river, near its source in Lake Erie. In 1812, two American attempts to capture Fort Erie were bungled by Brigadier General Alexander Smyth. Bad weather or poor administration halted the American efforts to cross the river, and Fort Erie remained in British hands.

In 1813, the Americans won the Battle of Fort George at the northern end of the Niagara River. At this point, the British abandoned the Niagara frontier and allowed Fort Erie to fall into American hands without a fight. Unfortunately, the Americans failed to follow up their victory, and later in the year they withdrew most of their soldiers from the Niagara to furnish an ill-fated attack on Montreal. This allowed the British to recover their prior positions and to mount raids which led to the Capture of Fort Niagara and the devastation of large parts of the American side of the Niagara River.

For 1814, a new invasion of Upper Canada was planned under the command of Major General Jacob Brown. Originally aimed at Kingston on Lake Ontario, it was switched to the Niagara because British ships controlled Lake Ontario for the first six months of 1814. The United States finally captured Fort Erie in 1814. It was thought that the British, while outnumbered, surrendered Fort Erie prematurely…at least in the view of the British commanders. They fully expected the outnumbered British troops to stand and fight…to the death, if need be. Because American troops were already concentrated at Buffalo and Black Rock, the attack was to be launched across the southern part of the Niagara frontier. Fort Erie was the first objective that stood in the way, and so, its capture was required. Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond, the British commander in Upper Canada, hoped that the garrison at Fort Erie could at least buy him enough time against the American invasion to concentrate his forces. Major Thomas Buck was given command of the fort with a garrison of 137 British soldiers.

Brown’s force crossed into Canada on July 3, 1814. Brigadier General Winfield Scott landed a mile and a half north of the fort with a brigade of regulars while it was still dark. Another brigade under Eleazar Wheelock Ripley crossed the head of the river to the south of the fort, a little behind schedule due to fog. Meanwhile, New York militia demonstrated opposite Chippewa to distract the British troops in the area. As Scott’s and Ripley’s forces approached Fort Erie, Buck fired only a few shots at the Americans from the fort’s cannon and then surrendered. The Americans had captured an important fort at little cost. The fort’s garrison had bought the British very little time and Buck was later court martialed for his hasty surrender.

From their new base at Fort Erie, Brown next marched up the Niagara River and met the British at the Battle of Chippewa. The British commander at Chippewa, Major General Phineas Riall, believed that the garrison of Fort Erie was still holding out, which contributed to his decision to launch a hasty and ill-fated attack. Following the Battle of Lundy’s Lane in July, British forces under the command of Gordon Drummond advanced and unsuccessfully attempted to besiege the fort. After that it remained in American hands until the American commanders decided to abandon the fort, which was evacuated and blown up in November 1814. These days, with so many historic forts across the nation, it was shocking to me to read that they had blown up the fort,

but I guess they weren’t interested in the historic side of things…they were making history. The fort, which had been built by the British in 1764, was restored, and was incorporated as a village in 1857. It became a town when it merged with Bridgeburg in 1932. Fort Erie is now the site of a large horse-racing track and has steel, aircraft, automotive, paint, and pharmaceutical industries. It is a town with a population of 29,960 in 2011.

but I guess they weren’t interested in the historic side of things…they were making history. The fort, which had been built by the British in 1764, was restored, and was incorporated as a village in 1857. It became a town when it merged with Bridgeburg in 1932. Fort Erie is now the site of a large horse-racing track and has steel, aircraft, automotive, paint, and pharmaceutical industries. It is a town with a population of 29,960 in 2011.

These days, some people are disenchanted with our country, and even willing to disrespect our flag, so I thought that today might be a good day to talk about our flag, our nation, and our national anthem. In the early days of our nation’s history, war was a rather common. The Revolutionary war and the freedom that came with it, did not mean that our enemies were done battling with us. In 1812, Britain was again at war with the United States, in the War of 1812, which lasted until 1815. British attempts to restrict United States trade, the Royal Navy’s impressment of American seamen and America’s desire to expand its territory, all contributed to the breakout of war. While there were defeats in battle, including the capture and burning of the nation’s capital, Washington DC, in August 1814, American troops were able to repulse British invasions in New York, Baltimore and New Orleans, which boosted national confidence and fostered a new spirit of patriotism. The ratification of the Treaty of Ghent on February 17, 1815, ended the war but left many of the most contentious questions unresolved. Nonetheless, many in the United States celebrated the War of 1812 as a “second war of independence,” beginning an era of partisan agreement and national pride. When I think of how things have changed since those days, I and both extremely sad and extremely mad.

These days, some people are disenchanted with our country, and even willing to disrespect our flag, so I thought that today might be a good day to talk about our flag, our nation, and our national anthem. In the early days of our nation’s history, war was a rather common. The Revolutionary war and the freedom that came with it, did not mean that our enemies were done battling with us. In 1812, Britain was again at war with the United States, in the War of 1812, which lasted until 1815. British attempts to restrict United States trade, the Royal Navy’s impressment of American seamen and America’s desire to expand its territory, all contributed to the breakout of war. While there were defeats in battle, including the capture and burning of the nation’s capital, Washington DC, in August 1814, American troops were able to repulse British invasions in New York, Baltimore and New Orleans, which boosted national confidence and fostered a new spirit of patriotism. The ratification of the Treaty of Ghent on February 17, 1815, ended the war but left many of the most contentious questions unresolved. Nonetheless, many in the United States celebrated the War of 1812 as a “second war of independence,” beginning an era of partisan agreement and national pride. When I think of how things have changed since those days, I and both extremely sad and extremely mad.

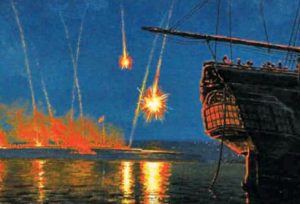

During the War of 1812, the friend of a man named Francis Scott Key was taken prisoner by the British. His  name was Dr William Beanes. Key went down to Baltimore, Maryland located the ship where Beanes was being held and negotiated his release. The British agreed to release Beanes, but would not let either of the men leave the ship until after the British bombardment of Fort McHenry. Key watched the bombing campaign unfold from aboard a ship located about eight miles away. After a day, the British were unable to destroy the fort and gave up. Key was relieved to see the American flag still flying over Fort McHenry and quickly penned a few lines in tribute to what he had witnessed. The date was September 13, 1814. The poem Key wrote that day…originally called “The Defense of Fort McHenry,” was changed to “The Star-Spangled Banner” in 1931. Most people would recognize that as our national anthem. The song told of the battle that Key was forced to watch, while praying that Fort McHenry could withstand the attack. That was probably one of the longest days of his life, but when the rockets would flash, he could see the flag, proudly waving…and afterward proclaiming the victory.

name was Dr William Beanes. Key went down to Baltimore, Maryland located the ship where Beanes was being held and negotiated his release. The British agreed to release Beanes, but would not let either of the men leave the ship until after the British bombardment of Fort McHenry. Key watched the bombing campaign unfold from aboard a ship located about eight miles away. After a day, the British were unable to destroy the fort and gave up. Key was relieved to see the American flag still flying over Fort McHenry and quickly penned a few lines in tribute to what he had witnessed. The date was September 13, 1814. The poem Key wrote that day…originally called “The Defense of Fort McHenry,” was changed to “The Star-Spangled Banner” in 1931. Most people would recognize that as our national anthem. The song told of the battle that Key was forced to watch, while praying that Fort McHenry could withstand the attack. That was probably one of the longest days of his life, but when the rockets would flash, he could see the flag, proudly waving…and afterward proclaiming the victory.

That flag and that song are both tributes to the brae men, and now women, who willingly fought and even gave  up their lives for this nation…for our freedom, the very freedom that allows it’s citizens to have free speech, which so many now use to disrespect our flag, our national anthem, our soldiers, and every respectful citizen of this country. These same people somehow wonder how we can be so upset with them…or maybe they know and like the drama queens they are, they love the drama of being on the wrong side of right and wrong. They just don’t like the consequences…such as people’s refusal to support them in their treason. As for me…I don’t believe in giving them any place in my story. I am a patriot…I will always be a patriot, and I will always honor our nation’s flag, anthem, and the soldiers who fought for our freedom.

up their lives for this nation…for our freedom, the very freedom that allows it’s citizens to have free speech, which so many now use to disrespect our flag, our national anthem, our soldiers, and every respectful citizen of this country. These same people somehow wonder how we can be so upset with them…or maybe they know and like the drama queens they are, they love the drama of being on the wrong side of right and wrong. They just don’t like the consequences…such as people’s refusal to support them in their treason. As for me…I don’t believe in giving them any place in my story. I am a patriot…I will always be a patriot, and I will always honor our nation’s flag, anthem, and the soldiers who fought for our freedom.

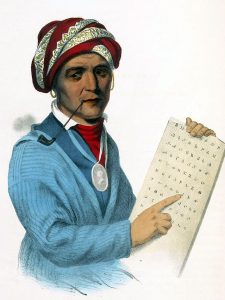

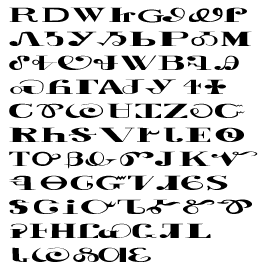

The Indian tribes in the United States had a spoken language, but in the early years they had no real need for a written language, other than hieroglyphics. At some point, a young Cherokee man named Sequoyah noticed something about the men in Andrew Jackson’s platoon, while he and some other Cherokee men were volunteering in the fight against the British in the War of 1812. In dealing with the Anglo soldiers and settlers, Sequoyah became intrigued by their “talking leaves” or printed books. Sequoyah realized that somehow the “talking leaves” recorded human speech. In a brilliant leap of logic, Sequoyah comprehended the basic nature of symbolic representation of sounds and in 1809 he began working on a similar system for the Cherokee language. Little did Sequoyah know that his work would change things, and in fact, change life for the Cherokee people. Still, it was not without it’s downside. Sequoyah was ridiculed and misunderstood by most of the Cherokee. Nevertheless, he made slow progress until he came up with the idea of representing each syllable in the language with a separate written character. Finally, he perfected his syllabary of 86 characters, a system that could be mastered in less than week. After obtaining the official endorsement of the Cherokee leadership, Sequoyah’s invention was soon adopted throughout the Cherokee nation.

The Indian tribes in the United States had a spoken language, but in the early years they had no real need for a written language, other than hieroglyphics. At some point, a young Cherokee man named Sequoyah noticed something about the men in Andrew Jackson’s platoon, while he and some other Cherokee men were volunteering in the fight against the British in the War of 1812. In dealing with the Anglo soldiers and settlers, Sequoyah became intrigued by their “talking leaves” or printed books. Sequoyah realized that somehow the “talking leaves” recorded human speech. In a brilliant leap of logic, Sequoyah comprehended the basic nature of symbolic representation of sounds and in 1809 he began working on a similar system for the Cherokee language. Little did Sequoyah know that his work would change things, and in fact, change life for the Cherokee people. Still, it was not without it’s downside. Sequoyah was ridiculed and misunderstood by most of the Cherokee. Nevertheless, he made slow progress until he came up with the idea of representing each syllable in the language with a separate written character. Finally, he perfected his syllabary of 86 characters, a system that could be mastered in less than week. After obtaining the official endorsement of the Cherokee leadership, Sequoyah’s invention was soon adopted throughout the Cherokee nation.

Finally, it was time for the next step. The General Council of the Cherokee Nation decided to purchase a  printing press. Their goal was to produce a newspaper in the Cherokee language. When the Cherokee-language printing press arrived on this day, February 21, 1828, the lead type was based on Sequoyah’s syllabary. Within months, the first Indian language newspaper in history appeared in New Echota, Georgia. It was called the Cherokee Phoenix. The Cherokee tribe was one of what the Americans called the “five civilized tribes” and they were native to the American Southeast. The Cherokee had long ago decided to embrace the United States’ program of “civilizing” Indians in the years after the Revolutionary War. In the minds of Americans, Sequoyah’s syllabary showed the Cherokee desire to fit into their dominant Anglo world. The Cherokee used their new press to print a bilingual version of the republican constitution. They also took many other steps to assimilate Anglo culture and practice while still preserving some aspects of their traditional language and beliefs. The press worked well, but would have been useless had it not been for the extraordinary work of Sequoyah.

printing press. Their goal was to produce a newspaper in the Cherokee language. When the Cherokee-language printing press arrived on this day, February 21, 1828, the lead type was based on Sequoyah’s syllabary. Within months, the first Indian language newspaper in history appeared in New Echota, Georgia. It was called the Cherokee Phoenix. The Cherokee tribe was one of what the Americans called the “five civilized tribes” and they were native to the American Southeast. The Cherokee had long ago decided to embrace the United States’ program of “civilizing” Indians in the years after the Revolutionary War. In the minds of Americans, Sequoyah’s syllabary showed the Cherokee desire to fit into their dominant Anglo world. The Cherokee used their new press to print a bilingual version of the republican constitution. They also took many other steps to assimilate Anglo culture and practice while still preserving some aspects of their traditional language and beliefs. The press worked well, but would have been useless had it not been for the extraordinary work of Sequoyah.

Sequoyah was born about 1770 in Tuskegee, Cherokee Nation, near present day Knoxville, Tennessee. He died  August 1843 at about 72 or 73, in San Fernando, Tamaulipas, Mexico. His name in English is George Gist or George Guess, which I find to be…well, crazy. Why was it necessary to butcher his name. Sequoyah was a Cherokee silversmith by trade, but his biggest claim to fame was the creation of written Cherokee. In 1821, when he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabary, he successfully made reading and writing in Cherokee possible. This was one of the very few times in recorded history that a member of a pre-literate people created an original, effective writing system. After seeing its worth, the people of the Cherokee Nation rapidly began to use his syllabary and officially adopted it in 1825. Their literacy rate quickly surpassed that of surrounding European-American settlers. In recognition of his service, the Cherokee Nation voted Sequoyah an annual allowance in 1841. He died two years later on a trip to San Fernando, seeking Cherokee to return to Oklahoma with him. The giant California redwood tree, Sequoia, was named after him.

August 1843 at about 72 or 73, in San Fernando, Tamaulipas, Mexico. His name in English is George Gist or George Guess, which I find to be…well, crazy. Why was it necessary to butcher his name. Sequoyah was a Cherokee silversmith by trade, but his biggest claim to fame was the creation of written Cherokee. In 1821, when he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabary, he successfully made reading and writing in Cherokee possible. This was one of the very few times in recorded history that a member of a pre-literate people created an original, effective writing system. After seeing its worth, the people of the Cherokee Nation rapidly began to use his syllabary and officially adopted it in 1825. Their literacy rate quickly surpassed that of surrounding European-American settlers. In recognition of his service, the Cherokee Nation voted Sequoyah an annual allowance in 1841. He died two years later on a trip to San Fernando, seeking Cherokee to return to Oklahoma with him. The giant California redwood tree, Sequoia, was named after him.

I think most of us have heard of the Barbary Coast at some point. The coast was named for its Berber inhabitants, but it was the trouble that occurred there that has made it a name to remember. The Barbary pirates, who were sometimes called Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, mostly near the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, which is now the area known as the Barbary Coast. In addition to seizing ships, they engaged in Razzias, raids on European coastal towns and villages, mainly in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal, but also in the British Isles, the Netherlands and as far away as Iceland. Their main goal was to capture Christian slaves for the Ottoman slave trade, as well as the general Arabic market in North Africa and the Middle East. The pirates captured thousands of ships and repeatedly raided coastal towns.

I think most of us have heard of the Barbary Coast at some point. The coast was named for its Berber inhabitants, but it was the trouble that occurred there that has made it a name to remember. The Barbary pirates, who were sometimes called Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, mostly near the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, which is now the area known as the Barbary Coast. In addition to seizing ships, they engaged in Razzias, raids on European coastal towns and villages, mainly in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal, but also in the British Isles, the Netherlands and as far away as Iceland. Their main goal was to capture Christian slaves for the Ottoman slave trade, as well as the general Arabic market in North Africa and the Middle East. The pirates captured thousands of ships and repeatedly raided coastal towns.

In order to combat the Barbary pirates, the United States Navy built the USS Constitution, which was a 44 gun  frigate. It was first launched on this day, October 21, 1797, from Boston Harbor. The USS Constitution performed well fighting off pirates in the area, and in 1805, a peace treaty was signed on her deck. When the conflict was over, the ship returned and to its base in Boston. I’m sure the pirates knew full well, that it would return if needed. The ship didn’t have to go back and flex it’s muscle again…at least not there.

frigate. It was first launched on this day, October 21, 1797, from Boston Harbor. The USS Constitution performed well fighting off pirates in the area, and in 1805, a peace treaty was signed on her deck. When the conflict was over, the ship returned and to its base in Boston. I’m sure the pirates knew full well, that it would return if needed. The ship didn’t have to go back and flex it’s muscle again…at least not there.

During the War of 1812, the USS Constitution won its nickname, Old Ironsides, after defeating the British warship, Guerriére in a furious battle off the coast of Nova Scotia. It was said that the British shots just bounced off the sides of the USS Constitution, as if they were made of iron, rather than wood, The Guerriére was thought to be invincible, but that was proven to be a fallacy. On the afternoon of 19 August 1812, about 400 miles southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, the Guerriére saw a sail in the distance, bearing down  on them. It was the USS Constitution, so the Guerriére prepared for action. Captain James Dacres mustered 244 men and 19 boys, and set them to prepare for battle. When the enemy hoisted American colors, Captain Dacres permitted the Americans in his crew to quit their guns. When the fight was over, nine men were killed and thirteen were wounded. Captain Dacres surrendered his badly damaged ship in an effort to save the lives of the remaining crew, the crew were taken prisoner, and the crew of the USS Constitution set the ship on fire. That was the end of the Guerriére, and Old Ironsides was born. The USS Constitution was retired from service in 1881, and served as a receiving ship until designated a museum ship in 1907.

on them. It was the USS Constitution, so the Guerriére prepared for action. Captain James Dacres mustered 244 men and 19 boys, and set them to prepare for battle. When the enemy hoisted American colors, Captain Dacres permitted the Americans in his crew to quit their guns. When the fight was over, nine men were killed and thirteen were wounded. Captain Dacres surrendered his badly damaged ship in an effort to save the lives of the remaining crew, the crew were taken prisoner, and the crew of the USS Constitution set the ship on fire. That was the end of the Guerriére, and Old Ironsides was born. The USS Constitution was retired from service in 1881, and served as a receiving ship until designated a museum ship in 1907.