wagon train

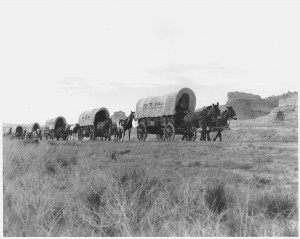

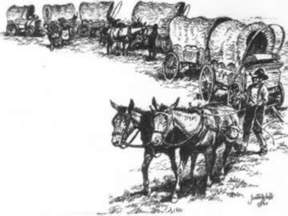

It was inevitable really…the migration of the people of the United States to the west coast, in search of gold, adventure, and more land. The east was filling up, and there was no place else to go, but west. Of course, many people would either not make it all the way to the West; choosing rather to homestead along the way, die, or actually make it to the West, and then return to the East. Nevertheless, before anyone could find out is life on the west coast suited them or not, they had to get to the west coast, and on May 16, 1842, the first major wagon train to the northwest departed from Elm Grove. Missouri, on the Oregon Trail. This was a little bit of a risky move, because US sovereignty over the Oregon Territory was not clearly established until 1846.

It was inevitable really…the migration of the people of the United States to the west coast, in search of gold, adventure, and more land. The east was filling up, and there was no place else to go, but west. Of course, many people would either not make it all the way to the West; choosing rather to homestead along the way, die, or actually make it to the West, and then return to the East. Nevertheless, before anyone could find out is life on the west coast suited them or not, they had to get to the west coast, and on May 16, 1842, the first major wagon train to the northwest departed from Elm Grove. Missouri, on the Oregon Trail. This was a little bit of a risky move, because US sovereignty over the Oregon Territory was not clearly established until 1846.

Nevertheless, American fur trappers and missionary groups had been living in the region for decades, along with Indians who had settled the land centuries earlier. Of course, everyone out there had a story to tell, and there were dozens of books and lectures that proclaimed Oregon’s agricultural potential. You can’t tell a story without creating interest somewhere. Even a boring story is of interest to someone, and this was no boring story. With the books and lectures coming out of the West, the white American farmers were very interested. They saw a chance to make their fortune, or at least to become independent. The actual first overland immigrants to Oregon, intended to farm primarily. A small band of 70 pioneers left Independence, Missouri in 1841. The stories they had heard from the fur traders brought them along the same route the traders had blazed, taking them west along the Platte River through the Rocky Mountains via the easy South Pass in Wyoming and then northwest to the Columbia River…basically through some on my own stomping grounds. Eventually, the trail they took was renamed by the pioneers, who called it the Oregon Trail.

The migration, once started, had little chance of being stopped, and in 1842, a slightly larger group of 100 pioneers made the 2,000-mile journey to Oregon. With the success of these two groups, the inevitable happened, accelerated in a major way by the severe depression in the Midwest, combined with a flood of propaganda from fur traders, missionaries, and government officials extolling the virtues of the land. They may have had good intentions, but it is never a good idea to lie to the public. With the disinformation on their minds, farmers dissatisfied with their prospects in Ohio, Illinois, Kentucky, and Tennessee, hoped to find better lives in the supposed paradise of Oregon. With that another type of “rush” began. Much like the “gold rush” years, the farmers saw the land as their “gold” and headed west.

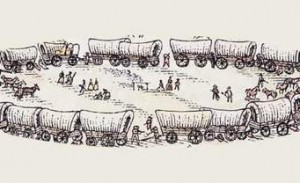

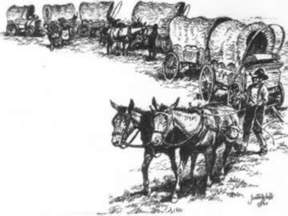

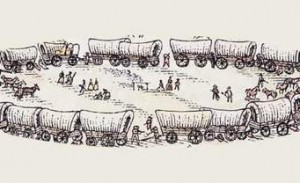

So, on this day in 1843, approximately 1,000 men, women, and children climbed aboard their wagons and steered their horses west out of the small town of Elm Grove, Missouri. It was the first real wagon train, comprised of more than 100 wagons with a herd of 5,000 oxen and cattle trailing behind. The train was led by Dr Elijah White, a Presbyterian missionary who had made the trip the year before. At first the trail was fairly easy, traveling over the flat lands of the Great Plains. There weren’t many obstacles in that area, and few river crossings, some of which could be dangerous for wagons. The bigger risk in the early days was the danger of Indian attacks, but they were still few and far between…at first anyway. The wagons were drawn into a circle at night to give the pioneers better protection from any attack that might come. They were very afraid of the Indians, who were enough different that they seemed deadly…to the pioneers anyway, and the Indians fear the White Man because of their weapons, and they were angry because the White Man wanted the land. In reality, the pioneers were far more in danger from seemingly mundane causes, like the accidental discharge of firearms, falling off mules or horses, drowning in river crossings, and disease. The trail became much more difficult, with steep ascents and descents over rocky terrain, after the train entered the mountains. The pioneers risked injury from overturned and runaway wagons.

Nevertheless, the wagon trains persevered, and the migrant movement continued until the West was populated. As for the 1,000-person party that made that original journey way back in 1843…the vast majority survived to reach their destination in the fertile, well-watered land of western Oregon. The next migration, in

1844 was smaller than that of the previous season, but in 1845 it jumped to nearly 3,000. Migration to the West was here to stay and the trains became an annual event, although the practice of traveling in giant convoys of wagons soon changed to many smaller bands of one or two-dozen wagons. The wagon trains really became a thing of the past in 1884, when the Union Pacific constructed a railway along the route.

1844 was smaller than that of the previous season, but in 1845 it jumped to nearly 3,000. Migration to the West was here to stay and the trains became an annual event, although the practice of traveling in giant convoys of wagons soon changed to many smaller bands of one or two-dozen wagons. The wagon trains really became a thing of the past in 1884, when the Union Pacific constructed a railway along the route.

During the gold rush years, in 1857, to be exact, two German men who had been traveling with a wagon train headed to California, decided to leave the rest of the group and headed out on their own. They wound up in the Mono Lake region of northern California. One of the men would later describe the area as “the burnt country.” While crossing the Sierra Nevada near the headwaters of the Owens River, they sat down to rest near a stream. Looking around, they noticed a curious looking rock ledge of red lava filled with what appeared to be pure lumps of gold “cemented” together. That was how their “mine” got its name.

During the gold rush years, in 1857, to be exact, two German men who had been traveling with a wagon train headed to California, decided to leave the rest of the group and headed out on their own. They wound up in the Mono Lake region of northern California. One of the men would later describe the area as “the burnt country.” While crossing the Sierra Nevada near the headwaters of the Owens River, they sat down to rest near a stream. Looking around, they noticed a curious looking rock ledge of red lava filled with what appeared to be pure lumps of gold “cemented” together. That was how their “mine” got its name.

The ledge of that hillside was literally loaded with the ore. The excited men couldn’t believe their eyes. One of the men was laughing at the other as he pounded away about ten pounds of the ore to take with him…because he did not believe it was really gold. The man who believe that it was gold drew a map to the location and the two men continued their journey. Along the way, the disbeliever died and since he was laden with so much ore, the believer tossed the majority of the samples. Then, after crossing the mountains, he followed the San Joaquin River to the mining camp of Millerton, California. After a long, weary journey, the German had become ill and soon went to San Francisco for treatment. He was diagnosed and cared for by a Doctor Randall who told the man he was terminally ill with consumption (tuberculosis). With no money to pay the doctor and too ill to return to the treasure, he paid his caretaker with the ore, the map he had drawn, and provided him with a detailed description.

Doctor Randall shared this knowledge with a few of his friends and together they decided to go for the gold. They arrived at old Monoville in the spring of 1861. After enlisting additional men to help, Randall’s group began to prospect on a quarter-section of land called Pumice Flat. Their claim is thought to have been some eight miles north of Mammoth Canyon…the 120 acres were near what became known as Whiteman’s Camp. Word of possibly a huge cache of gold spread quickly and before long miners flooded the area hunting for the gold laden red “cement.” One story tells that two of Doctor Randall’s party had in fact found the “Cement Mine,” taking several thousand dollars from the ledge. Unfortunately, for those two men, the area was filled with the Owens Valley Indian War which began in 1861. The Paiute Indians, who had heretofore been generally peaceful, were angered at the large numbers of prospectors who had invaded their lands. The two miners who  had allegedly found the lost ledge were killed by the Indians before they were able to tell of its location.

had allegedly found the lost ledge were killed by the Indians before they were able to tell of its location.

Though the “cement” outcropping was never found again, the many prospectors who flooded the eastern Sierra region did find gold. Apparently there was a huge cache there after all. This resulted in the mining camps of Dogtown, Mammoth City, Lundy Canyon, Bodie, and many others. The lost lode is said to lie somewhere in the dense woods near the Sierra Mountain headwaters of the San Joaquin River’s middle fork. If it really exists, it must be very well hidden.

As kids growing up, my sisters and I were subjected to many stories, view, songs, and events that centered around the Old West. When I say subjected, I don’t mean that we hated every minute of I, because we didn’t. We lived in Wyoming, and therefore we embraced the Old West. I can’t say that my sisters and I always liked all things western, because that would be false too. We all went through our Rock and Roll era, and during that time, we pretty much hated Country music, although shows like Bonanza, the Rifleman, Wagon Train, and The Virginian…just to name a few, were among our favorites, and we each had our favorite actors, and we were going to “marry” them. I know, silly…right?

As kids growing up, my sisters and I were subjected to many stories, view, songs, and events that centered around the Old West. When I say subjected, I don’t mean that we hated every minute of I, because we didn’t. We lived in Wyoming, and therefore we embraced the Old West. I can’t say that my sisters and I always liked all things western, because that would be false too. We all went through our Rock and Roll era, and during that time, we pretty much hated Country music, although shows like Bonanza, the Rifleman, Wagon Train, and The Virginian…just to name a few, were among our favorites, and we each had our favorite actors, and we were going to “marry” them. I know, silly…right?

Back then, the Old West was still considered something that people were proud to know about, or even to know people who lived those times. It was the times that our grandparents grew up in, and that  made it even more cool. I don’t suppose that the kids of today look back on the Old West or even the 1950s, 1960s, or 1970s, as being cool, because those times were before personal computers and cell phones, so I’m sure it seemed like the dark ages to the kids of today. Those years were probably best known for protests…unless you compare that era to today’s, when everyone is so offended by everything. Even when I look back on my childhood years, I can’t say that I think we as a generation did anything so amazing…at least not until we grew up, because of course, it is our generation that invented the computer and cell phone. Nevertheless, it was a vastly different era that the Old West…or maybe that’s just my opinion.

made it even more cool. I don’t suppose that the kids of today look back on the Old West or even the 1950s, 1960s, or 1970s, as being cool, because those times were before personal computers and cell phones, so I’m sure it seemed like the dark ages to the kids of today. Those years were probably best known for protests…unless you compare that era to today’s, when everyone is so offended by everything. Even when I look back on my childhood years, I can’t say that I think we as a generation did anything so amazing…at least not until we grew up, because of course, it is our generation that invented the computer and cell phone. Nevertheless, it was a vastly different era that the Old West…or maybe that’s just my opinion.

While we were little, many of the cities and states were celebrating their centennial years, and it was a big deal!! Contests were held to see who could grow the best beard, and I’m sure who had the best Old Western costume. My Dad, Allen Spencer, decided to grow a beard for the competition. I don’t know if he won or not, or even if he entered any contest at all, but he got in on the festivities…as did Dad’s girls. We each had a long dress, much like the women of the Old West wore, and our parents took pictures to document the events. It was a great time, and they made sure that they had plenty of pictures of it.

These days, you seldom hear of such events. I don’t know if states or cities are  just not at the right point, or if many people have just lost interest, or what has happened exactly, but you don’t see these things happening. I find that sad, because our family found it to be very fun and interesting. Of course, there are still reinactments of old western robberies, the pony express, and wagons west trips, and I think those would be fun, but for some reason that centennial just seemed different…more interesting somehow…like we were a real pioneer family.

just not at the right point, or if many people have just lost interest, or what has happened exactly, but you don’t see these things happening. I find that sad, because our family found it to be very fun and interesting. Of course, there are still reinactments of old western robberies, the pony express, and wagons west trips, and I think those would be fun, but for some reason that centennial just seemed different…more interesting somehow…like we were a real pioneer family.

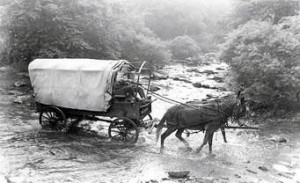

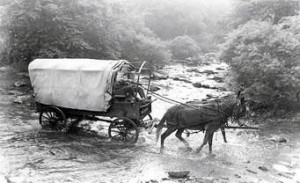

This summer when Bob and I were in the Black Hills, we were looking around in the gift shop at Mount Rushmore, when I came across a book called “Women’s Diaries Of The Westward Journey.” Since then, I have been thinking about what it must have been like to travel in a covered wagon…especially for a woman. Of course, times were different back then, and people did not have the luxury of a daily shower, or even a real bathroom…and that was in their own homes. So, imagine what life would be like on a wagon, traveling in a wagon train headed west in the mid-1800s. As the emigrants were traveling west, they were making their own roads, hunting their own food, and cooking over a campfire. For a lot of people, I’m sure this sounds like going camping, but then imagine doing it for months at a time. A day’s travel averaged about twelve to twenty miles, meaning that on the plains, they often stopped for the day within sight of the site they had just left that morning. For travelers now, that would seem insanely slow, but for the wagon trains, it was just the normal day’s journey. They knew no other way.

This summer when Bob and I were in the Black Hills, we were looking around in the gift shop at Mount Rushmore, when I came across a book called “Women’s Diaries Of The Westward Journey.” Since then, I have been thinking about what it must have been like to travel in a covered wagon…especially for a woman. Of course, times were different back then, and people did not have the luxury of a daily shower, or even a real bathroom…and that was in their own homes. So, imagine what life would be like on a wagon, traveling in a wagon train headed west in the mid-1800s. As the emigrants were traveling west, they were making their own roads, hunting their own food, and cooking over a campfire. For a lot of people, I’m sure this sounds like going camping, but then imagine doing it for months at a time. A day’s travel averaged about twelve to twenty miles, meaning that on the plains, they often stopped for the day within sight of the site they had just left that morning. For travelers now, that would seem insanely slow, but for the wagon trains, it was just the normal day’s journey. They knew no other way.

People back then would have been somewhat crazy to set out alone for the west…or to set out any later than spring, because either scenario was bound to fail. They needed the protection of the wagon train, as well as the  additional supplies, should a wagon be lost to fire, a river crossing, or an attack by Indians. It was their back up plan. They couldn’t just stop at the next town at a store and buy more supplies. There were no towns, stores, or even roads. When we travel, even in the rural state of Wyoming that I live in, we are used to seeing miles with very little to catch the eye, other that an occasional farm house, and an occasional town, but remember that we have roads to follow so we don’t lose our way. And even then, many of us use GPS to make sure we are taking the right road. They had none of that. They had to use the sun and landmarks to make sure they were going the right direction. They depended on people who had taken this trip before them. It was all they had. I think most of us today would go nuts if we never saw a house, a road, or a town. We would wonder if we were insane for setting out on this crazy adventure at all. One woman wrote to her husband, who was waiting at the end of the line, with the spelling ability she had at the time, “I can tell you nothing only that were hear and its strange I wish we had never started … it seems impossible to get their.” She had set out in a wagon train with her four children, without her husband, and that in itself must have been scary.

additional supplies, should a wagon be lost to fire, a river crossing, or an attack by Indians. It was their back up plan. They couldn’t just stop at the next town at a store and buy more supplies. There were no towns, stores, or even roads. When we travel, even in the rural state of Wyoming that I live in, we are used to seeing miles with very little to catch the eye, other that an occasional farm house, and an occasional town, but remember that we have roads to follow so we don’t lose our way. And even then, many of us use GPS to make sure we are taking the right road. They had none of that. They had to use the sun and landmarks to make sure they were going the right direction. They depended on people who had taken this trip before them. It was all they had. I think most of us today would go nuts if we never saw a house, a road, or a town. We would wonder if we were insane for setting out on this crazy adventure at all. One woman wrote to her husband, who was waiting at the end of the line, with the spelling ability she had at the time, “I can tell you nothing only that were hear and its strange I wish we had never started … it seems impossible to get their.” She had set out in a wagon train with her four children, without her husband, and that in itself must have been scary.

Days on the wagon train began long before dawn with a simple breakfast of coffee, bacon, and dry bread. After breakfast, the people secured their supplies, hitched up their teams, and hit the trail by seven o’clock in the morning. Most people walked because of lack of space, and the fact that the wagon was so uncomfortable. The  train stopped at noon for a cold meal of coffee, beans, and bacon, which had been prepared that morning. During this break, called nooning, men and women would gather and talk, children would play, and animals would rest. After that, the travel would continue until around six o’clock in the evening, when they wagons would circle for the night. Some people would visit after supper, but most went to bed, because they were exhausted. Some slept in the wagon, but most slept on the ground, because oddly enough it was more comfortable. While traveling west on the wagon trains was a necessary journey to be made to grow this country, it was not an easy journey to make, and for that reason, I have to stand in awe of those who did it.

train stopped at noon for a cold meal of coffee, beans, and bacon, which had been prepared that morning. During this break, called nooning, men and women would gather and talk, children would play, and animals would rest. After that, the travel would continue until around six o’clock in the evening, when they wagons would circle for the night. Some people would visit after supper, but most went to bed, because they were exhausted. Some slept in the wagon, but most slept on the ground, because oddly enough it was more comfortable. While traveling west on the wagon trains was a necessary journey to be made to grow this country, it was not an easy journey to make, and for that reason, I have to stand in awe of those who did it.

The other day, I was talking with my cousin, Shirley Cameron on instant message through Facebook, when she brought up an old memory…a blast from our past. Shirley’s mom, Ruth Wolfe was my dad, Allen Spencer’s younger sister, and our families were very close…especially when the Wolfe family still lived in Casper, and we were all little kids. Shirley was the oldest of the three Wolfe siblings, with two younger brothers, Larry and Terry. My older sister, Cheryl Masterson fell in between Larry and Terry, and I was four months younger than Terry. Our three younger sisters, Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, and Allyn Hadlock were the youngest ones. Back in those days, the fun you had depended on your imagination. I guess we all had imagination, but Shirley really seemed to be able to come up with great ideas. And she was able to carry them out too.

The other day, I was talking with my cousin, Shirley Cameron on instant message through Facebook, when she brought up an old memory…a blast from our past. Shirley’s mom, Ruth Wolfe was my dad, Allen Spencer’s younger sister, and our families were very close…especially when the Wolfe family still lived in Casper, and we were all little kids. Shirley was the oldest of the three Wolfe siblings, with two younger brothers, Larry and Terry. My older sister, Cheryl Masterson fell in between Larry and Terry, and I was four months younger than Terry. Our three younger sisters, Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, and Allyn Hadlock were the youngest ones. Back in those days, the fun you had depended on your imagination. I guess we all had imagination, but Shirley really seemed to be able to come up with great ideas. And she was able to carry them out too.

We started talking about the games we played when we were out at their place, like wagon train. Of course, we didn’t have a real covered wagon or a team of horses, but that didn’t mean that we would have to be the  horses for our pull type wagons, because My aunt and uncle had a tractor, and Shirley knew how to drive it. So we hooked the wagons to the tractor, and headed down the road near their place. Oh sure, sometimes the whole thing would break down, but then what would a wagon train be without a breakdown. Even in the pioneer days, the wagons broke down…right?

horses for our pull type wagons, because My aunt and uncle had a tractor, and Shirley knew how to drive it. So we hooked the wagons to the tractor, and headed down the road near their place. Oh sure, sometimes the whole thing would break down, but then what would a wagon train be without a breakdown. Even in the pioneer days, the wagons broke down…right?

Shirley had a set of dishes, and like the wagon trains of the wild west, we brought our own food the long trip…usually. Of course, sometimes we had to improvise. Since we didn’t really have a way to go hunting, we had to make due with what was available to us, and the best cooking we did was when we made mud pies. They probably didn’t taste good, and I’ll never know, because I never tasted them, but we could make them look pretty good…in a hamburger sort of way. I’m sure there were other things like vegetables picked out of Aunt Ruth’s garden, and maybe apples or berries that we came across, whether they were edible or not. No matter what we came up with, real or imagined, we always had a lot of fun playing wagon train or any other game we came up with to play. It was always interesting, but I think in reality it was Shirley who had all the great  ideas…maybe with a little help from Cheryl.

ideas…maybe with a little help from Cheryl.

We were all as close as sisters or best friends, but we were more than that…we were cousins, and that is a forever friend…kind of like a sister is a forever friend. For Shirley, we were like the sisters she never had. Of course, we didn’t really understand what a big deal that was, because we were five sisters. We had never really known a time without our sisters, but Shirley had two brothers, and even though they were close, they weren’t like sisters. Boys think differently than girls. They like to do different things than girls. It just wasn’t the same. Yes, we played the games the boys wanted to play too sometimes, but we sure had a good time playing wagon train with Shirley.