voting

For many years, in the United States, women were not allowed to vote. Of course, many women didn’t have much of a formal education either. They might have gone to the sixth grade or something, but then it was thought that they should be at home with their mothers, learning to run a household, cook, and raise children. It was thought that political matters should be left to the men, “who understood these things.” I don’t believe that the men were being intentionally chauvinistic, but it was simply the way things were in that day and age.

For many years, in the United States, women were not allowed to vote. Of course, many women didn’t have much of a formal education either. They might have gone to the sixth grade or something, but then it was thought that they should be at home with their mothers, learning to run a household, cook, and raise children. It was thought that political matters should be left to the men, “who understood these things.” I don’t believe that the men were being intentionally chauvinistic, but it was simply the way things were in that day and age.

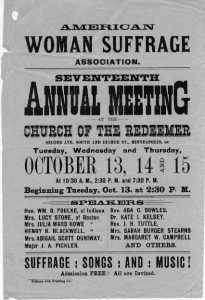

Lydia Taft became the first legal woman voter in colonial America in 1756. Under British rule in the Massachusetts Colony, in the New England town meeting in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, Taft voted on at least three occasions. The British law at the time stated that “unmarried white women who owned property could vote in New Jersey.” The law was in place from 1776 to 1807. After 1807, things pretty much went back to the “only men can possibly understand politics, sweetie” mentality, and women couldn’t vote until 1869, when Wyoming granted women the right to vote. Utah followed in 1870. Prior to the 19th Amendment, individual states made their own decisions on women’s suffrage, according to Time magazine. In fact, most states allowed women to vote in at least some elections prior to 1920, with only eight of 48 states completely disenfranchising women. Still, even when they weren’t allowed to vote, nothing prohibited women from running for office in many cases…and they often did. Thousands of women ran for office prior to 1920 and many of them won and served long before they were legally allowed to vote.

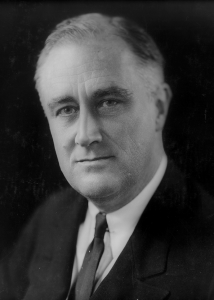

As far as presidents go, it hit me that while many wives, mothers, sisters, and daughters had a husband, son, brother, or father who was president, the first 31 of those presidents were elected without the votes of the women in their families. In fact, Franklin D Roosevelt’s mother was the first mom who got to cast a vote for her son as president. How strange that must have felt. I’m sure that anyone who finds themselves related to the President of the United States, might find life a little bit surreal, but that first ability to vote for that family member…wow!! Of course, the whole idea of being able to legally vote after fighting for the privilege so hard must have been surreal in itself…whether you know the candidate personally or not.

Before the summer of 1971, a person had to be 21 years old in order to vote. That was before the 26 Amendment was signed into law, on July 5, 1971, by President Richard Nixon. The amendment had passed through the Senate, House, and states in record time, lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, but it was not a quick victory. The battle was hard-fought, mostly by young people between the ages of 18 and 21, who were eligible to be drafted, but didn’t have the right to vote. The battle had raged since World War II.

Before the summer of 1971, a person had to be 21 years old in order to vote. That was before the 26 Amendment was signed into law, on July 5, 1971, by President Richard Nixon. The amendment had passed through the Senate, House, and states in record time, lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, but it was not a quick victory. The battle was hard-fought, mostly by young people between the ages of 18 and 21, who were eligible to be drafted, but didn’t have the right to vote. The battle had raged since World War II.

When the United States joined in the World War II war effort, it didn’t take long to find that they were going to need more men. It wasn’t that so many were killed, although that certainly was a problem too, but less than a year in, President Roosevelt and his administration faced a serious dilemma. They had 20 million eligible men who were registered for the draft, but 50% of them were rejected either for health reasons or because they were deemed illiterate. The United States had to have more men, and there was only one place to get them…expand the eligible draft ages. So, on November 11, 1942, Congress approved lowering the minimum draft age to 18 and raising the maximum to 37. Soon after, the slogan “Old enough to fight, old enough to vote” was born. For the over 21 draftees, the right to vote was already theirs, but the 18 to 20 year olds did not, and they felt like if they could be asked to fight and die, they should be able to vote…like ither adults, and much like the fight we have today with “old enough to fight, old enough to drink.” I’m not sure the current protestors will win their battle, however.

The changing of the voting age didn’t come easy either. Many people thought that 18-year-olds were just too young to understand politics. West Virginia congressman Jennings Randolph became the first supporter for lowering the age. In 1942, he introduced the first of 11 bills he sponsored over his tenure in Congress. Despite support from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and a number of senators and representatives, Congress failed to pass any legislation. Nevertheless, a popular movement was growing. Finally, in 1943, Georgia became the first  state to lower the voting age for state and local elections to 18, with Kentucky following suit in 1955. It broke the ice. While these young voters couldn’t vote for US offices, they had a say in their own state. The movement to lower the voting age began to gain grassroots traction when newly elected President Dwight D Eisenhower expressed his support in his 1954 State of the Union address, “For years our citizens between the ages of 18 and 20 have, in time of peril, been summoned to fight for America. They should participate in the political process that produces this fateful summons. I urge Congress to propose to the States a constitutional amendment permitting citizens to vote when they reach the age of 18.”

state to lower the voting age for state and local elections to 18, with Kentucky following suit in 1955. It broke the ice. While these young voters couldn’t vote for US offices, they had a say in their own state. The movement to lower the voting age began to gain grassroots traction when newly elected President Dwight D Eisenhower expressed his support in his 1954 State of the Union address, “For years our citizens between the ages of 18 and 20 have, in time of peril, been summoned to fight for America. They should participate in the political process that produces this fateful summons. I urge Congress to propose to the States a constitutional amendment permitting citizens to vote when they reach the age of 18.”

While it was gaining momentum, it was still slow-going. It would not be until much of the American public became disillusioned by the lengthy and costly war in Vietnam in the mid 1960s that the movement to lower the voting age gained widespread public support. “Old enough to fight, old enough to vote” found its way back into the American consciousness in the form of protest signs and chants. The push was revived, and then-Senator Randolph and other politicians continued to push legislation to lower the age to 18, including passing an amendment into 1965’s Voting Rights Act in 1970 that applied lowering the age to federal, state, and local elections. As the amendment was being signed into law, President Nixon thought it might be problematic. He issued a public statement that the federal government regulating state and local elections was likely to be “deemed unconstitutional and that only an amendment would secure this right.” He was right, and the amendment was struck down in the 1970 Supreme Court case Oregon v. Mitchell, ruling that the federal government could not make mandates for state and local elections. That meant that the fight continued. The initial result was a mixed system in which state and local elections had different rules than federal elections. That brought with it logistical problems on election days in states across the country, bringing more protests and lobbying efforts. The biggest problem was the 18 to 20 year olds worrying that their draft numbers were being called despite having no say in electing their representation. “Project 18” continued to put the pressure on legislators to take action. Marches were held all over the nation.

Finally, their hard work paid off. On March 10, 1971, the Senate voted unanimously in favor of a Constitutional amendment lowering the voting age to 18, followed by an overwhelming majority of the House voting in favor on March 23, 1971. The states quickly ratified the amendment, and it took effect on July 1, 1971, nearly 30 years after Senator Randolph first proposed lowering the voting age. In response to its passing, the senator remarked, “I believe that our young people possess a great social conscience, are perplexed by the injustices which exist in the world and are anxious to rectify these ills.” Finally, those who were “old enough to fight” could also vote.

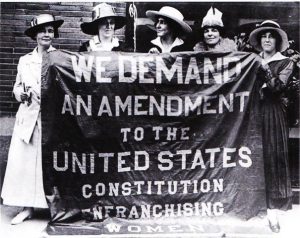

Anytime a group wants to change something in their nation, there is controversy. It really doesn’t matter what the change is, or whether it is good or bad for the country, there will always be people who are against it. The Women’s Suffrage movement, was no different. For more that seventy years, women had been fighting for the right to vote. From the founding of the United States they had not been allowed to vote, and I think originally it was simply because women were viewed as fragile and really to be protected. It didn’t really occur to the men that women could understand politics, wars, and government matters. They were to delicate. That opinion was largely accepted by the women too, until about 1849…73 years after our nation gained its independence from Great Britain. Then some of the women started thinking that they were are smart as the men, and should be allowed to vote too. They were right, of course, but their victory would not come without a long, hard battle. For many years the women who were fighting to vote were look at as

Anytime a group wants to change something in their nation, there is controversy. It really doesn’t matter what the change is, or whether it is good or bad for the country, there will always be people who are against it. The Women’s Suffrage movement, was no different. For more that seventy years, women had been fighting for the right to vote. From the founding of the United States they had not been allowed to vote, and I think originally it was simply because women were viewed as fragile and really to be protected. It didn’t really occur to the men that women could understand politics, wars, and government matters. They were to delicate. That opinion was largely accepted by the women too, until about 1849…73 years after our nation gained its independence from Great Britain. Then some of the women started thinking that they were are smart as the men, and should be allowed to vote too. They were right, of course, but their victory would not come without a long, hard battle. For many years the women who were fighting to vote were look at as  somehow being bold, and well simply not very refined. Proper women were encouraged to avoid them. The men heckled them. Everyone thought of these women as being somewhat trashy.

somehow being bold, and well simply not very refined. Proper women were encouraged to avoid them. The men heckled them. Everyone thought of these women as being somewhat trashy.

I can’t say for sure, just what it was that finally tipped the scales in favor of the women’s right to vote, but quite possibly it had something to do with the “squeaky wheel getting the oil” in the end. Nevertheless, like anything worth fighting for, you continue to fight until you win, or until there is no hope of winning. For the women of the United States, the battle would be won. Changes are sometimes tough to swallow…especially when we think they are  morally wrong. It doesn’t matter what day and age we live in, or what the issue is, someone, somewhere is going to be against the new idea. There will be battles that should be won and those that probably shouldn’t. Nevertheless, like it or not, once a new idea is made law, it usually stays law, unless the law is changed later on. Thankfully, for women everywhere, the right to vote was not repealed, and it will always be our right.

morally wrong. It doesn’t matter what day and age we live in, or what the issue is, someone, somewhere is going to be against the new idea. There will be battles that should be won and those that probably shouldn’t. Nevertheless, like it or not, once a new idea is made law, it usually stays law, unless the law is changed later on. Thankfully, for women everywhere, the right to vote was not repealed, and it will always be our right.

On this day August 26, 1920, the 19th Amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote, is adopted into the United States Constitution by proclamation of Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby. Women could vote now and forever. People born since 1920, which is most of us, have no concept of the enormity of that amendment. It changed the face of politics, government, and campaigning forever. Not only could women vote, but they could run for office too. And that idea has been up for debate ever since.