United States

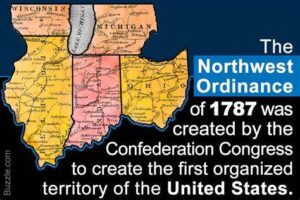

It never really occurred to me that the formation of new states in the United States would be the huge undertaking that it actually became. I just assumed that as the settlers moved into an area, they eventually got populated enough to decide to be a state. Of course, I realized that they would have to “petition” the national government for acceptance, but that wasn’t all there was to it at all. The United States had acquired the Northwest Territory (the Midwest today) in a number of steps. First, when it was relinquished by the British. Second, extinguishment of states’ claims west of the Appalachians. And finally, usurpation or purchase of lands from the Native Americans. Originally, the Hudson’s Bay Company acquired the area under a charter from Charles II in 1670. Then, in 1869, the Canadian government bought the land from the company. The boundaries we now have were set in 1912. In 1870, Canada acquired an area known as Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company for £300,000 (Canadian $1.5 million) and a large land grant.

It never really occurred to me that the formation of new states in the United States would be the huge undertaking that it actually became. I just assumed that as the settlers moved into an area, they eventually got populated enough to decide to be a state. Of course, I realized that they would have to “petition” the national government for acceptance, but that wasn’t all there was to it at all. The United States had acquired the Northwest Territory (the Midwest today) in a number of steps. First, when it was relinquished by the British. Second, extinguishment of states’ claims west of the Appalachians. And finally, usurpation or purchase of lands from the Native Americans. Originally, the Hudson’s Bay Company acquired the area under a charter from Charles II in 1670. Then, in 1869, the Canadian government bought the land from the company. The boundaries we now have were set in 1912. In 1870, Canada acquired an area known as Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company for £300,000 (Canadian $1.5 million) and a large land grant.

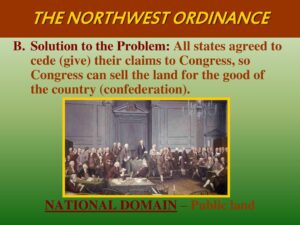

That left the United States with a kind of dilemma, since they wanted to make sure these new states were run in the way they had originally designed. So, on July 13, 1787, Congress enacts the Northwest Ordinance, to structure the settlement of the Northwest Territory. Since the formation of new states was a new venture for  the young nation, they had to create a policy for the addition of these new states. Vitally important was the need to make sure their new nation thrived and survived. The members of Congress knew that if their new confederation were to survive intact, it had to resolve issue of the states’ competing claims to western territory.

the young nation, they had to create a policy for the addition of these new states. Vitally important was the need to make sure their new nation thrived and survived. The members of Congress knew that if their new confederation were to survive intact, it had to resolve issue of the states’ competing claims to western territory.

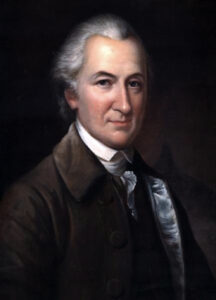

That said, in 1781, the state of Virginia began the process by ceding its extensive land claims to Congress. That bold move made other states more comfortable in doing the same. Thomas Jefferson first proposed a method of incorporating these western territories into the United States in 1784. His plan was to basically turn the territories into colonies of the existing states. Since each state was to have their own constitution, the ten new northwestern territories would select the constitution of an existing state that closely aligned with their own values. Once that process was complete, the new territory (colony) had to wait until its population reached 20,000 to join the confederation as a full member. That process made Congress nervous, because they feared that the new states…10 in the Northwest as well as Kentucky, Tennessee and Vermont…would quickly gain enough power to outvote the old ones, so Congress never passed Thomas Jefferson’s proposal.

It would be three more years before the Northwest Ordinance which proposed that “three to five new states be created from the Northwest Territory. Instead of adopting the legal constructs of an existing state, each territory would have an appointed governor and council. When the population reached 5,000, the residents could elect their own assembly, although the governor would retain absolute veto power. When 60,000 settlers  resided in a territory, they could draft a constitution and petition for full statehood. The ordinance provided for civil liberties and public education within the new territories, but did not allow slavery.”

resided in a territory, they could draft a constitution and petition for full statehood. The ordinance provided for civil liberties and public education within the new territories, but did not allow slavery.”

The last part angered the pro-slavery Southerners, but they were willing to go along with this because they hoped that the new states would be populated by white settlers from the South. They believed that although these Southerners would have no enslaved workers of their own, they would not join the growing abolition movement of the North. Of course, we all know how that played out.

Recently, my sisters, Cheryl Masterson, Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, Allyn Hadlock, and I started a book club. Before each meeting, we read a book, on our own time, and then come together to discuss the book we read. We chose the Presidents of the United States as our topics, and each time we progress to the next president. We began at the beginning, President George Washington. We went on to John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and next will be James Monroe. One takeaway from these books has been that while our founding fathers may have had their faults, and some more than others, each tried to do what they saw as the best thing for this nation. They also knew that more than anything, we needed freedom. We could not continue to live under British rule.

Recently, my sisters, Cheryl Masterson, Caryl Reed, Alena Stevens, Allyn Hadlock, and I started a book club. Before each meeting, we read a book, on our own time, and then come together to discuss the book we read. We chose the Presidents of the United States as our topics, and each time we progress to the next president. We began at the beginning, President George Washington. We went on to John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and next will be James Monroe. One takeaway from these books has been that while our founding fathers may have had their faults, and some more than others, each tried to do what they saw as the best thing for this nation. They also knew that more than anything, we needed freedom. We could not continue to live under British rule.

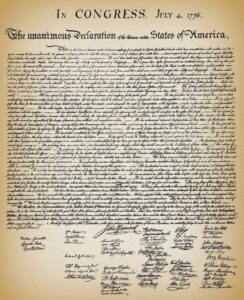

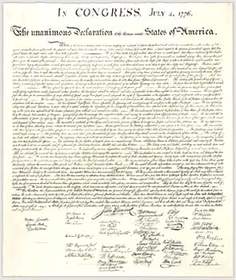

We had to be free of England, and so it was that Independence Day, also known as the Fourth of July, is now a federal holiday in the United States commemorating that freedom, and the Declaration of Independence, which  was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States of America. The Declaration of Independence was largely written by Thomas Jefferson but was collectively the work of the Committee of Five, which also included John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. The Founding Father delegates of the Second Continental Congress declared that “the Thirteen Colonies were no longer subject (and subordinate) to the monarch of Britain, King George III, and were now united, free, and independent states.” The Congress voted to approve independence by passing the Lee Resolution on July 2 and adopted the Declaration of Independence two days later, on July 4. We were a free nation, but that did not mean that Great Britain would willingly accept that. In fact, Great Britain did not accept US independence until 1783…a full seven years after it was first declared.

was ratified by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, establishing the United States of America. The Declaration of Independence was largely written by Thomas Jefferson but was collectively the work of the Committee of Five, which also included John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. The Founding Father delegates of the Second Continental Congress declared that “the Thirteen Colonies were no longer subject (and subordinate) to the monarch of Britain, King George III, and were now united, free, and independent states.” The Congress voted to approve independence by passing the Lee Resolution on July 2 and adopted the Declaration of Independence two days later, on July 4. We were a free nation, but that did not mean that Great Britain would willingly accept that. In fact, Great Britain did not accept US independence until 1783…a full seven years after it was first declared.

Like many “start-up” countries, the United States met with heavy opposition the minute it tried to get going. The “Mother Country” didn’t want to let go. Great Britain called the United States the “Colonies” long after we

were actually a free nation. Even when they knew they had lost any control over the United States, they tried to get it back, and in the absence of getting their control back, they downplayed the importance of the United States. That was probably the most ridiculous part of it, because the United States became the most powerful nation in the world. While some might disagree, and while we have had our ups and downs, this nation will always stand. Today, we celebrate the nation that we love. The United States of America…the home of the free, because of the brave. Happy Independence Day to this great nation!! Let the celebration begin!!

were actually a free nation. Even when they knew they had lost any control over the United States, they tried to get it back, and in the absence of getting their control back, they downplayed the importance of the United States. That was probably the most ridiculous part of it, because the United States became the most powerful nation in the world. While some might disagree, and while we have had our ups and downs, this nation will always stand. Today, we celebrate the nation that we love. The United States of America…the home of the free, because of the brave. Happy Independence Day to this great nation!! Let the celebration begin!!

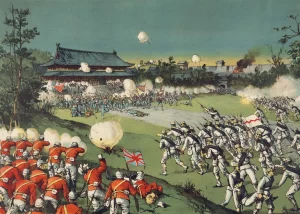

For nearly a month beginning June 17, 1900, the man who would become President Herbert Hoover and his wife, Lou were caught up in what was to become known as the Boxer Rebellion in China. During the Boxer Rebellion, the community of foreigners the Hoovers lived in, in the city of Tianjin, was besieged and under attack. You might wonder how a future president could be caught up in such a situation, but remember, he wasn’t president yet. He was a citizen. After they were married in Monterey, California, on February 10, 1899, Herbert and Lou Hoover left on a honeymoon cruise to China. Following their honeymoon, Hoover started his new job as a mining consultant to the Chinese emperor with the consulting group Bewick, Moreing and Company.

For nearly a month beginning June 17, 1900, the man who would become President Herbert Hoover and his wife, Lou were caught up in what was to become known as the Boxer Rebellion in China. During the Boxer Rebellion, the community of foreigners the Hoovers lived in, in the city of Tianjin, was besieged and under attack. You might wonder how a future president could be caught up in such a situation, but remember, he wasn’t president yet. He was a citizen. After they were married in Monterey, California, on February 10, 1899, Herbert and Lou Hoover left on a honeymoon cruise to China. Following their honeymoon, Hoover started his new job as a mining consultant to the Chinese emperor with the consulting group Bewick, Moreing and Company.

In 1900, a Chinese secret organization called the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists led an uprising in northern China against the spread of Western and Japanese influence there. The uprising would become known as the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. The rebels performed calisthenics rituals and martial arts that they believed would give them the ability to withstand bullets and other forms of attack. Westerners referred to these rituals as shadow boxing, leading to the Boxers nickname. They also killed foreigners and Chinese Christians, and they destroyed foreign property.

The Boxers besieged the foreign district of China’s capital city Beijing, which was called Peking then, from June to August. It was at that point that an international force that included American troops ended the uprising. By the terms of the Boxer Protocol, which officially ended the rebellion in 1901, China agreed to pay more than $330 million in reparations. In the end, America returned the money it received from China after the Boxer Rebellion, on the condition it be used to fund the creation of a university in Beijing. Other nations involved later remitted their shares of the Boxer indemnity too.

Western nations and Japan had forced China’s ruling Qing dynasty to accept wide foreign control over the country’s economic affairs by the end of the 19th century. China had resisted the efforts throughout the Opium  Wars of 1839-1842 and 1856-1860, by means of popular rebellions and the Sino-Japanese War, but without a modernized military, China had suffered millions of casualties.

Wars of 1839-1842 and 1856-1860, by means of popular rebellions and the Sino-Japanese War, but without a modernized military, China had suffered millions of casualties.

John Hay, the US Secretary of State from 1898 to 1905, began to implement an “Open Door Policy” to push for American and European influence over the Chinese trade and economic partnerships. The Open Door Policy called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy was met with indifference or resistance by other key players, including the Qing Empress Dowager Tzu’u Hzi, but it brought continued Western influence over domestic Chinese affairs, and it set the stage for the rebellion.

The Boxers came from various parts of society, but many were peasants, particularly from Shandong province, which had been struck by natural disasters such as famine and flooding. These things made them particularly volatile. In the 1890s, China had given territorial and commercial concessions in this area to several European nations, and the Boxers blamed their poor standard of living on foreigners who were colonizing their country.

The siege stretched into weeks, and the diplomats (including the Hoovers), their families, and guards suffered through hunger and degrading conditions as they fought to keep the Boxers at bay, while the Western powers and Japan organized a multinational force to crush the rebellion. It is thought that several hundred foreigners and several thousand Chinese Christians were killed during this time. On August 14, after fighting its way through northern China, the rescue began, when an international force of approximately 20,000 troops from eight nations, including Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States arrived to take Beijing. The Boxer Rebellion formally ended with the signing of the Boxer Protocol on September 7, 1901. “By terms of the agreement, forts protecting Beijing were to be destroyed, Boxer and Chinese government officials involved in the uprising were to be punished, foreign legations were permitted to

station troops in Beijing for their defense, China was prohibited from importing arms for two years and it agreed to pay more than $330 million in reparations to the foreign nations involved.” The Qing dynasty, which was established in 1644, was weakened by the Boxer Rebellion. Following an uprising in 1911, the dynasty came to an end and China became a republic in 1912.

station troops in Beijing for their defense, China was prohibited from importing arms for two years and it agreed to pay more than $330 million in reparations to the foreign nations involved.” The Qing dynasty, which was established in 1644, was weakened by the Boxer Rebellion. Following an uprising in 1911, the dynasty came to an end and China became a republic in 1912.

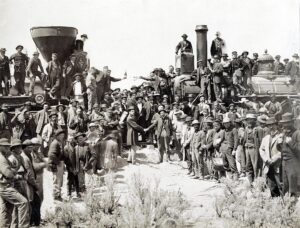

When people started moving west in the United States, the trips took approximately four months by wagon train. At that time, saying “goodbye” to loved ones was a very sad moment, because many times people would never see each other again. The distance was just too great and the cost too much, and unless people were moving permanently, they simply couldn’t take the trip. At that time…the 1860s, they likely had no idea that things would get easier either.

When people started moving west in the United States, the trips took approximately four months by wagon train. At that time, saying “goodbye” to loved ones was a very sad moment, because many times people would never see each other again. The distance was just too great and the cost too much, and unless people were moving permanently, they simply couldn’t take the trip. At that time…the 1860s, they likely had no idea that things would get easier either.

Nevertheless, just a short sixteen years later, all that changed. The train wasn’t a completely new invention in the 1860s, and in fact was invented in 1829. Still, as the United States was experiencing its expansion to the west, there were few towns and no railroads. So, moving west still meant that families might never see their departing loved ones again, and if the did, it would be a number of years. During the early 19th century, when Thomas Jefferson first dreamed of an American nation stretching from “sea to shining sea,” it took the president 10 days to travel the 225 miles from Monticello to Philadelphia via carriage. The distance from New York to San Francisco (which was founded in 1776, but didn’t become part of the United States until the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848). Jefferson was president from 1801 to 1809. The distance from New York City to San Francisco is 2,565 miles from New York City, making the carriage time in those days approximately 114 days, or a little less than a third of a year. If you weren’t moving west, you would also have to make the return trip. It just wasn’t feasible.

Jefferson saw a possible answer to his dilemma as early as 1802, with “the introduction of so powerful an agent as steam.” At that time, he predicted, the possibility of “a carriage on wheels” that would make “a great change in the situation of man.” For Jefferson, the change would not come soon enough, and he never witnessed the  “carriage on wheels” he had envisioned. Nevertheless, within half a century, America would have more railroads than any other nation in the world, and by 1869, America would see the first transcontinental line linking the coasts was completed. Now, those journeys that were impossible for any reason but moving, that had previously taken months using horses, could be made in less than a week. In fact, on June 4, 1876, the Transcontinental Express train traveled from New York City to San Francisco in a mere 83 hours.

“carriage on wheels” he had envisioned. Nevertheless, within half a century, America would have more railroads than any other nation in the world, and by 1869, America would see the first transcontinental line linking the coasts was completed. Now, those journeys that were impossible for any reason but moving, that had previously taken months using horses, could be made in less than a week. In fact, on June 4, 1876, the Transcontinental Express train traveled from New York City to San Francisco in a mere 83 hours.

It seemed inconceivable that a human being could travel across the entire nation in less than four days. Nevertheless, now the impossible had become not only possible, but a reality, and the United States became a very mobile nation. Prior to that time, the coast were months apart, and it was speculated that the nation couldn’t possibly stay united. They couldn’t even communicate very well, much less see each other. Now, those problems were in the past. Just five days later, daily passenger service began. You simply can’t hold progress back. Once the technology is available, the reality isn’t far behind. Americans were amazed at the speed and comfort of this new form of travel. Of course, it wasn’t for everyone, because as with all new inventions, it was expensive and therefore, only for the wealthy. The train was luxurious, with first-class passengers riding in beautifully appointed cars with plush velvet seats that converted into snug sleeping berths. The finer amenities included steam heat, fresh linen daily and gracious porters who catered to their every whim. For an extra $4 a day, the wealthy traveler could opt to take the weekly Pacific Hotel Express, which offered first-class dining on board. As one happy passenger wrote, “The rarest and richest of all my journeying through life is this three-thousand miles by rail.”

A third-class ticket could be purchased for only $40–less than half the price of the first-class fare. At this low rate, the traveler received no luxuries. Their cars, fitted with rows of narrow wooden benches, were congested,  noisy and uncomfortable. The railroad often attached the coach cars to freight cars that were constantly shunted aside to make way for the express trains. Consequently, the third-class traveler’s journey west might take 10 or more days. Still, no one complained, because 10 days was far better than four months, and sitting on a hard bench seat was still much better than six months walking alongside a Conestoga wagon on the Oregon Trail. Of course, this amazing method of transportation would only be amazing for a short time in history, as trains gave way to cars and eventually airplanes. Still those things were either a way off, or would have to wait for the necessary roads and airports to make those forms of travel available. Trains were here now, and life was good!!

noisy and uncomfortable. The railroad often attached the coach cars to freight cars that were constantly shunted aside to make way for the express trains. Consequently, the third-class traveler’s journey west might take 10 or more days. Still, no one complained, because 10 days was far better than four months, and sitting on a hard bench seat was still much better than six months walking alongside a Conestoga wagon on the Oregon Trail. Of course, this amazing method of transportation would only be amazing for a short time in history, as trains gave way to cars and eventually airplanes. Still those things were either a way off, or would have to wait for the necessary roads and airports to make those forms of travel available. Trains were here now, and life was good!!

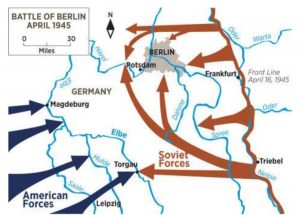

Sometimes, an event that potentially changed history, ends up getting little or no recognition. Thankfully, the picture that marked the event was taken, or the entire event might never have been noticed in history at all. This particular day is actually a very important day in the history of World War II, and therefore, the world. Elbe Day, which took place on April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau in Germany. This event marked an important step toward the end of World War II in Europe. If you have ever heard the saying, divide and conquer, you will know basically what happened on Elbe Day. A secret mission had been planned, and April 25, 1945, was the day it was carried out.

Sometimes, an event that potentially changed history, ends up getting little or no recognition. Thankfully, the picture that marked the event was taken, or the entire event might never have been noticed in history at all. This particular day is actually a very important day in the history of World War II, and therefore, the world. Elbe Day, which took place on April 25, 1945, is the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, near Torgau in Germany. This event marked an important step toward the end of World War II in Europe. If you have ever heard the saying, divide and conquer, you will know basically what happened on Elbe Day. A secret mission had been planned, and April 25, 1945, was the day it was carried out.

The plan was to have the Soviet army advance from the East, and the US Army advance from the West. The first contact between American and Soviet patrols occurred near Strehla exactly as planned, after First Lieutenant Albert Kotzebue, an American soldier, crossed the Elbe River in a boat with three men of an intelligence and reconnaissance platoon. Once they crossed to the east bank of the river, they met up with  forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of the First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gardiev. Later that day, another patrol under Second Lieutenant William Robertson with Frank Huff, James McDonnell and Paul Staub met a Soviet patrol commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Silvashko on the destroyed Elbe bridge of Torgau. When the two armies connected at the Elbe River, the cutting of Germany in half is accomplished. In doing so, the strength of the German army was severely weakened. The German army was split in two, just like the country was, and in the end, that split made it impossible for the Germans to really fight the war they were engaged in. It was the beginning of the end for them.

forward elements of a Soviet Guards rifle regiment of the First Ukrainian Front, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Gardiev. Later that day, another patrol under Second Lieutenant William Robertson with Frank Huff, James McDonnell and Paul Staub met a Soviet patrol commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Silvashko on the destroyed Elbe bridge of Torgau. When the two armies connected at the Elbe River, the cutting of Germany in half is accomplished. In doing so, the strength of the German army was severely weakened. The German army was split in two, just like the country was, and in the end, that split made it impossible for the Germans to really fight the war they were engaged in. It was the beginning of the end for them.

Finally, on April 26, the commanders of the 69th Infantry Division of the First Army (United States) and the 58th Guards Rifle Division of the 5th Guards Army (Soviet Union) met at Torgau, southwest of Berlin. They knew that this moment was monumental, and it had to be documented. Arrangements were made for the  formal “Handshake of Torgau” photo to be taken of Robertson and Silvashko the following day, April 27. The Soviet, American, and British governments released simultaneous statements that evening in London, Moscow, and Washington, “reaffirming the determination of the three Allied powers to complete the destruction of the Third Reich.” They knew they must have victory at all costs.

formal “Handshake of Torgau” photo to be taken of Robertson and Silvashko the following day, April 27. The Soviet, American, and British governments released simultaneous statements that evening in London, Moscow, and Washington, “reaffirming the determination of the three Allied powers to complete the destruction of the Third Reich.” They knew they must have victory at all costs.

The fact that Elbe Day has never been an official holiday in any country, has not stopped people from looking to the day as something very special, and in the years after 1945 the memory of this friendly encounter gained new significance in the context of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

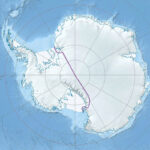

Over the centuries, there have been many exploratory expeditions all over the world. Some were privately financed, while others were financed by groups, governments, kings and as in the case of the 1955 to 1958 expedition to Antartica, the Commonwealth of England. The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) was an expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, by way of the South Pole. It was also the first expedition to reach the South Pole overland for 46 years. t was preceded only by Amundsen’s expedition and Scott’s expedition in 1911 and 1912. Antartica is a fierce, snow and ice covered, wilderness, which makes me wonder why anyone would want to be on an expedition there. Nevertheless, I suppose that it’s the adventure of it that attracts so many to attempts it.

Over the centuries, there have been many exploratory expeditions all over the world. Some were privately financed, while others were financed by groups, governments, kings and as in the case of the 1955 to 1958 expedition to Antartica, the Commonwealth of England. The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition (CTAE) was an expedition that successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, by way of the South Pole. It was also the first expedition to reach the South Pole overland for 46 years. t was preceded only by Amundsen’s expedition and Scott’s expedition in 1911 and 1912. Antartica is a fierce, snow and ice covered, wilderness, which makes me wonder why anyone would want to be on an expedition there. Nevertheless, I suppose that it’s the adventure of it that attracts so many to attempts it.

Traditionally, polar expeditions of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration were private ventures, and the CTAE was no exception, even though it was supported by the governments of the United Kingdom, New Zealand, United States, Australia and South Africa, as well as many corporate and individual donations, under the patronage of Queen Elizabeth II. The expedition was headed by British explorer Vivian Fuchs and included New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary. The group from New Zealand included scientists who were participating in International Geophysical Year research while the British team were separately based at Halley Bay.

Fuchs took the Danish Polar vessel, Magga Dan and went for additional supplied, returning in December 1956. The southern summer of 1956–1957 was spent consolidating Shackleton Base and establishing the smaller South Ice Base, located about 300 miles inland to the south. The winter of 1957 found Fuchs at Shackleton Base. Then, finally, he set out on the transcontinental journey in November 1957. The twelve-man team traveled in six vehicles, three Sno-Cats, two Weasel tractors, and one specially adapted Muskeg tractor. While they traveled, the team was also tasked with carrying out scientific research including seismic soundings and  gravimetric readings. This was, after all a scientific expedition.

gravimetric readings. This was, after all a scientific expedition.

Hillary’s team began setting up Scott Base. This was going to be the final destination for Fuchs. It was located on the opposite side of the continent at McMurdo Sound on the Ross Sea. Using three converted Ferguson TE20 tractors and one Weasel, which had to be abandoned part-way, Hillary and his three men…Ron Balham, Peter Mulgrew, and Murray Ellis…were responsible for route-finding and laying a line of supply depots up the Skelton Glacier and across the Polar Plateau on towards the South Pole, for the use of Fuchs on the final leg of his journey. The remaining member of Hillary’s team carried out geological surveys around the Ross Sea and Victoria Land areas. The Hillary team was not originally supposed to travel as far as the South Pole, but when the supply depots were completed, Hillary saw the opportunity to beat the British and continued south, thereby reaching the Pole…where the US Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station had recently been established by air, on January 3, 1958. While he wasn’t supposed to go, Hillary’s party became the third team to reach the South Pole, preceded by Roald Amundsen in 1911 and Robert Falcon Scott in 1912. Hillary’s arrival also marked the first time that land vehicles had ever reached the Pole. It was a great historic moment.

Fuchs’ team finally reached the Pole from the opposite direction on January 19, 1958, where they met up with Hillary. From there, Fuchs continued overland, following the route that Hillary had forged to get to the South Pole. Then, Hillary flew back to Scott Base in a US plane. He would later rejoin Fuchs by plane for part of the remaining overland journey. The original overland party finally arrived at Scott Base on March 2, 1958, after having completed the historic crossing of 2,158 miles of previously unexplored snow and ice in 99 days. A few days later the expedition members left Antarctica on the on the New Zealand naval ship Endeavour, headed for New Zealand, with Captain Harry Kirkwood at the helm.

Although large quantities of supplies were hauled overland, many forms of resources were used in the expedition. Both parties were also equipped with light aircraft and made extensive use of air support for reconnaissance and supplies. US personnel working in Antartica at the time provided additional logistical help. Both parties also used dog teams for fieldwork trips and backup in case of failure of the mechanical transportation. The dogs were not taken all the way to the Pole. In December 1957 four men from the

expedition flew one of the planes…a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter—on an 11-hour, 1,430-mile, non-stop trans-polar flight across the Antarctic continent from Shackleton Base by way of the Pole to Scott Base, following roughly by air the same route as Fuchs’ overland party. For his accomplishments, Fuchs was knighted. The second overland crossing of the continent did not occur until 1981, during the Transglobe Expedition led by Ranulph Fiennes.

expedition flew one of the planes…a de Havilland Canada DHC-3 Otter—on an 11-hour, 1,430-mile, non-stop trans-polar flight across the Antarctic continent from Shackleton Base by way of the Pole to Scott Base, following roughly by air the same route as Fuchs’ overland party. For his accomplishments, Fuchs was knighted. The second overland crossing of the continent did not occur until 1981, during the Transglobe Expedition led by Ranulph Fiennes.

“Who was Winston Churchill?” It’s not a question you often hear, because Winston Churchill had a presence. His features were distinct, but he was not a big man. Churchill stood 5’6½” tall and weighed 187 pounds. He was maybe 35 pounds overweight, but not in bad health, especially considering he smoked as many as ten cigars a day, and when you consider that he lived to be 90 years old, it would seem that none of the normal “risk factors” applied to Winston Churchill. He dealt with daily stress, poor eating habits, excess weight, and smoking, but outlived many people in this era or that. How people felt about Winston Churchill, depended on which side of the subject in question they were on. When he made up his mind on a matter, he rarely changed his mind, and he didn’t back down.

“Who was Winston Churchill?” It’s not a question you often hear, because Winston Churchill had a presence. His features were distinct, but he was not a big man. Churchill stood 5’6½” tall and weighed 187 pounds. He was maybe 35 pounds overweight, but not in bad health, especially considering he smoked as many as ten cigars a day, and when you consider that he lived to be 90 years old, it would seem that none of the normal “risk factors” applied to Winston Churchill. He dealt with daily stress, poor eating habits, excess weight, and smoking, but outlived many people in this era or that. How people felt about Winston Churchill, depended on which side of the subject in question they were on. When he made up his mind on a matter, he rarely changed his mind, and he didn’t back down.

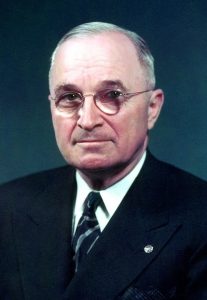

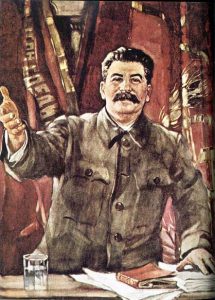

He was responsible for one of the most famous speeches of the Cold War period. It was a speech in which former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill condemned the Soviet Union’s policies in Europe and declared, “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.” Churchill’s Cold War speech is one of the “opening volleys” announcing the beginning of the Cold War. When he was defeated for re-election as prime minister in 1945, he was invited to Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, which is where he gave this speech. President Harry S Truman joined Churchill on the platform and listened intently to his speech. Expressing praise for the United States, Churchill declared that the United States stood “at the pinnacle of world power.” England and the United States have long had a “friendly, but competitive relationship,” and it would soon become quite clear that a primary purpose of his talk was to argue for an even closer “special relationship” between the United States and Great Britain…the two great powers of the “English-speaking world.” But, would it be in the best interest of the United States to agree?

World War II had ended, and as in any post war situation, things were still pretty chaotic. Nevertheless, it was necessary to set policies, and to organize the losing countries so that things didn’t escalate out of control

again…not an easy task. The Soviet Union was well known for its expansionistic policies and was unlikely to stop trying to take over its neighbors without some kind of intervention. In addition to the “iron curtain” that had descended across Eastern Europe, Churchill spoke of “communist fifth columns” that were operating throughout western and southern Europe. Churchill compared the Soviet Union to disastrous consequences of the appeasement of Hitler prior to World War II, saying that in dealing with the Soviets there was “nothing which they admire so much as strength, and there is nothing for which they have less respect than for military weakness.” Therefore, without intervention, they would quickly get back to the same disastrous practices they used before, and the war would have to fought all over again.

again…not an easy task. The Soviet Union was well known for its expansionistic policies and was unlikely to stop trying to take over its neighbors without some kind of intervention. In addition to the “iron curtain” that had descended across Eastern Europe, Churchill spoke of “communist fifth columns” that were operating throughout western and southern Europe. Churchill compared the Soviet Union to disastrous consequences of the appeasement of Hitler prior to World War II, saying that in dealing with the Soviets there was “nothing which they admire so much as strength, and there is nothing for which they have less respect than for military weakness.” Therefore, without intervention, they would quickly get back to the same disastrous practices they used before, and the war would have to fought all over again.

The speech was well received by Truman and many other US officials. Everyone knew the truth, and somebody simply had to come right out and say it. They had decided that because the Soviet Union was determined to expand, only a tough stance on a united front would deter the Russians. Churchill’s “iron curtain” phrase immediately entered the official vocabulary of the Cold War. It was a term everyone knew, and it perfectly described the problem. Of course, agreeing with Churchill, didn’t necessarily mean that the US officials enthusiastic about Churchill’s call for a “special relationship” between the United States and Great Britain. They weren’t concerned that Great Britain would again try to have some influence over the United States, but rather they were well aware that Britain’s power was weakening, and the US had no intention of being used as pawns to help support the crumbling British empire.

Of course, the Russian leader Joseph Stalin had a very different view of the speech, saying that it was “war

mongering” and referred to Churchill’s comments about the “English-speaking world” as imperialist “racism.” The British, Americans, and Russians, all of whom were allies against Hitler less than a year before the speech, were now drawing the battle lines of the Cold War. It didn’t take long for the similarities between Hitler and the Soviet Union to become glaringly clear, and they had to be stopped. I don’t know why dictators feel the need to enslave other people. The “Iron Curtain” would “come down” like all other forms of tyranny must eventually do, but unfortunately, a lot of lives are lost before victory is achieved.

mongering” and referred to Churchill’s comments about the “English-speaking world” as imperialist “racism.” The British, Americans, and Russians, all of whom were allies against Hitler less than a year before the speech, were now drawing the battle lines of the Cold War. It didn’t take long for the similarities between Hitler and the Soviet Union to become glaringly clear, and they had to be stopped. I don’t know why dictators feel the need to enslave other people. The “Iron Curtain” would “come down” like all other forms of tyranny must eventually do, but unfortunately, a lot of lives are lost before victory is achieved.

The Cold War, and the Soviet Union’s sudden announcement on August 30, 1961, to end a three-year moratorium on nuclear testing, brought about a shift in US policy, and a number of to nuclear test operations. One, known as Operation Fishbowl was a series of high-altitude nuclear tests in 1962 that were carried out by the United States as a part of the larger Operation Dominic nuclear test program. Flight-test vehicles were designed and manufactured by Avco Corporation. The test planned for the first half of 1962, called Bluegill, Starfish and Urraca were originally planned for the first half of 1962, but the first test attempt was delayed until June. Planning was complex, but necessary.

The Cold War, and the Soviet Union’s sudden announcement on August 30, 1961, to end a three-year moratorium on nuclear testing, brought about a shift in US policy, and a number of to nuclear test operations. One, known as Operation Fishbowl was a series of high-altitude nuclear tests in 1962 that were carried out by the United States as a part of the larger Operation Dominic nuclear test program. Flight-test vehicles were designed and manufactured by Avco Corporation. The test planned for the first half of 1962, called Bluegill, Starfish and Urraca were originally planned for the first half of 1962, but the first test attempt was delayed until June. Planning was complex, but necessary.

The launch sites were planned from Johnston Island in the Pacific Ocean north of the equator. The island was the chosen launch site, rather than the other locations in the Pacific Proving Grounds. However, the testing was not without push back. Even as early as 1958, Lewis Strauss, t hen chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, opposed doing any high-altitude tests at locations that had been used for earlier Pacific nuclear tests. The motivation for concern was the fear of the flash from the nighttime high-altitude detonations might blind civilians who were living on nearby islands. Still, Johnston Island was a remote location. It was more distant from populated areas than the other potential test locations. Nevertheless, in order to protect residents of the Hawaiian Islands from flash blindness or permanent retinal injury from the bright nuclear flash, the nuclear missiles of Operation Fishbowl were launched toward the southwest of Johnston Island. The detonation part of the test would be farther from Hawaii.

hen chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, opposed doing any high-altitude tests at locations that had been used for earlier Pacific nuclear tests. The motivation for concern was the fear of the flash from the nighttime high-altitude detonations might blind civilians who were living on nearby islands. Still, Johnston Island was a remote location. It was more distant from populated areas than the other potential test locations. Nevertheless, in order to protect residents of the Hawaiian Islands from flash blindness or permanent retinal injury from the bright nuclear flash, the nuclear missiles of Operation Fishbowl were launched toward the southwest of Johnston Island. The detonation part of the test would be farther from Hawaii.

The Urraca test involved about a 1 megaton yield at very high altitude of just over 621 miles. With the damage caused to satellites by the Starfish Prime detonation, the proposed Urraca test was always controversial. Because they couldn’t put the fears to rest, the Urraca test was finally canceled, and an extensive re-evaluation of the Operation Fishbowl plan as a whole was made during the 82-day operations pause after the Bluegill Prime disaster of July 25, 1962. When prime was added to a test, it indicated that the main test had failed, so when Bluegill Prime failed, it was the second test fail for that test series, which in this case (Bluegill Double Prime), ended in disaster when the Thor suffered a stuck valve preventing the flow of LOX to the combustion chamber. The engine lost thrust and unburned RP-1 spilled down into the hot thrust chamber, igniting and starting a fire around the base of the missile. Bluegill would go on to have two more tests, before they finally achieved success.

A test named Kingfish was added during the early stages of Operation Fishbowl planning. Two low-yield tests, Checkmate and Tightrope, were also added during the project, so the final number of tests in Operation Fishbowl was five. Tightrope was the last atmospheric nuclear test conducted by the United States, as the Limited Test Ban Treaty came into effect shortly thereafter. A total of Seven rockets carrying scientific instrumentation were launched from Johnston Island in support of the Tightrope test, which was the final atmospheric test conducted by the United States. I suppose testing is necessary, and I don’t know where else or how else it could be done, but the whole thing seems crazy to me. I do think that in light of this and other nuclear test disasters, care should be taken to better protect human life.

The American Revolutionary War actually began on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. At that time, it wasn’t considered a full-blown war, and attempts were still being made by July 5, 1775, to avoid that full-blown war. The Olive Branch Petition, adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8th, was the final attempt to avoid the full-blown war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America, that became known as the American Revolutionary War, and ended with full independence of the United States.

The American Revolutionary War actually began on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. At that time, it wasn’t considered a full-blown war, and attempts were still being made by July 5, 1775, to avoid that full-blown war. The Olive Branch Petition, adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8th, was the final attempt to avoid the full-blown war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America, that became known as the American Revolutionary War, and ended with full independence of the United States.

It seemed that in the early days of the Revolutionary War, the main weapon was a volley of petitions and proclamations. The Second Continental Congress had already authorized the invasion of Canada more than a week earlier, but the Olive Branch Petition affirmed American loyalty to Great Britain, asking King George III to prevent further conflict. The petition was followed up with a July 6th Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, making the success of the Olive Branch Petition unlikely in London. By August 1775, London officially declared the colonies to be in rebellion by the Proclamation of Rebellion, and the Olive Branch Petition was rejected by the British government. In fact, King George had refused to read it before declaring that the colonists were traitors.

The Second Continental Congress convened in May 1775. At that time, most and most delegates followed John Dickinson in his quest to reconcile with King George. He could not picture a world with an independent United States. I suppose there are always those people without a vision for the future. However, there was a small group of delegates, led by John Adams, who could see that war was inevitable, and that we would need to become independent of Great Britain. Nevertheless, there is a right time, so they decided that the wisest course of action was to remain quiet and wait for the opportune time to rally the people. This allowed Dickinson and his followers to pursue their own course for a reconciliation that would ultimately never happen.

Dickinson was the primary author of the Olive Branch Petition, along with Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, John Rutledge, and Thomas Johnson, all of whom also served on the drafting committee. Dickinson claimed that the colonies did not want independence, but rather, wanted more equitable trade and tax regulations. He asked that the King establish a lasting settlement between the Mother Country and the colonies “upon so firm a basis as to perpetuate its blessings, uninterrupted by any future dissensions, to succeeding generations in both countries” beginning with the repeal of the Intolerable Acts. The introductory paragraph of the letter named twelve of the thirteen colonies, all except Georgia. The letter was approved on July 5 and signed by John Hancock, President of the Second Congress, and by representatives of the named twelve colonies. It was sent to London on July 8, 1775, in the care of Richard Penn and Arthur Lee. Dickinson hoped that news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord combined with the “humble petition” would persuade the King to respond with a counterproposal or open negotiations.

Finally, Adams wrote to a friend, telling him that the petition served no purpose. Everyone knew that war was inevitable. Adams said that the colonies should have already raised a navy and taken the British officials prisoner. Unfortunately, the letter was intercepted by British officials and news of its contents reached Great Britain at about the same time as the petition itself. British advocates of a military response used Adams’ letter to claim that the petition itself was insincere, and it was rejected. The hostilities which Adams had foreseen undercut the petition, and the King had answered it before it even reached him.

With the King’s refusal to consider the petition, came the opportunity Adams and others needed to push for independence. Now the colonists viewed the King as unwilling and uninterested concerning the colonists’ grievances. The colonists finally knew that they had just two choices…complete independence or complete submission to British rule. They chose complete independence, and the rest, as we all know, is history.

While Independence Day is celebrated on July 4th each year, with all the festivities, days off, barbecues, and fireworks, our nation…formally known as the thirteen colonies, actually obtained legal separation from Great Britain on July 2, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia declaring the United States independent from Great Britain’s rule. Called the Lee Resolution, it was also known as “The Resolution for Independence” and was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2nd. The Lee Resolution resolved that the Thirteen Colonies, at the time referred to as the United Colonies, were “free and independent states” and were now separate from the British Empire. The resolution created what became the United States of America.

While Independence Day is celebrated on July 4th each year, with all the festivities, days off, barbecues, and fireworks, our nation…formally known as the thirteen colonies, actually obtained legal separation from Great Britain on July 2, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress voted to approve a resolution of independence that had been proposed in June by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia declaring the United States independent from Great Britain’s rule. Called the Lee Resolution, it was also known as “The Resolution for Independence” and was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2nd. The Lee Resolution resolved that the Thirteen Colonies, at the time referred to as the United Colonies, were “free and independent states” and were now separate from the British Empire. The resolution created what became the United States of America.

After passing the vote for independence, Congress could turn its attention to the Declaration of Independence, which would be the official statement explaining this decision. The Declaration of Independence had been prepared by a Committee of Five, with Thomas Jefferson as its principal author. While Jefferson collaborated extensively with the other four members of the Committee of Five, i,t was largely his writing and his wording that made up the Declaration of Independence. It was composed in isolation over 17 days between June 11, 1776, and June 28, 1776. Jefferson was renting the second floor of a three-story private home at 700 Market Street in Philadelphia at the time. The house, within walking distance of Independence Hall, is now known as the Declaration House.

Of course, as with any document brought before Congress, they debated and revised the wording of the Declaration, and for reasons unknown, removed wording in which Jefferson had vigorously denounced King George III for importing the slave trade. They finally approved the document two days later on July 4th. John

Adams wrote a letter to his wife, Abigail, on July 3rd, stating, “The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

Adams wrote a letter to his wife, Abigail, on July 3rd, stating, “The second day of July 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more.”

Of course, as we all know, Adams’s prediction was off by two days. Nevertheless, his idea that a day should be celebrated forever, did become a tradition, not on July 2nd, but rather on July 4th, because of the Declaration of Independence. That was because of the date shown on the much-publicized Declaration of Independence, rather than the date the resolution of independence was approved in a closed session of Congress. In addition, historians have disputed whether members of Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, even though Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin all later wrote that they had signed it on that day. Many historians believe that the Declaration was signed nearly a month after its adoption, on August 2, 1776, and not on July 4th as many have believed. Nevertheless, they have been unable to prove their theory or to change the date on which we celebrate our independence.

One thing that I find very interesting is the fact that both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who were the only two signatories of the Declaration of Independence later to serve as presidents of the United States, both

died on the same day…July 4, 1826, and within five hours of each other. They were also the last surviving members of the original American revolutionaries. It was also the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. James Monroe, while not a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, but who was another Founding Father who was elected president, also died on July 4, 1831, making him the third President who died on the anniversary of independence. There was one president who was born on Independence Day…Calvin Coolidge, who was born on July 4, 1872.

died on the same day…July 4, 1826, and within five hours of each other. They were also the last surviving members of the original American revolutionaries. It was also the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. James Monroe, while not a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, but who was another Founding Father who was elected president, also died on July 4, 1831, making him the third President who died on the anniversary of independence. There was one president who was born on Independence Day…Calvin Coolidge, who was born on July 4, 1872.