united states navy

At the onset of the Civil War, combat involved bayonets, horses, wooden ships, and inaccurate artillery. As the war progressed, the armaments evolved to include mines, precise firearms, more lethal bullets, torpedoes, and ironclad ships as the new norm. Although the majority of battles were fought on land, the struggle for naval supremacy was a pivotal aspect of the war. Control over the coastline meant control over vital imports from Europe and Coastal America, including essential supplies like clothing, food, artillery, medicine, and occasionally, reinforcements.

At the onset of the Civil War, combat involved bayonets, horses, wooden ships, and inaccurate artillery. As the war progressed, the armaments evolved to include mines, precise firearms, more lethal bullets, torpedoes, and ironclad ships as the new norm. Although the majority of battles were fought on land, the struggle for naval supremacy was a pivotal aspect of the war. Control over the coastline meant control over vital imports from Europe and Coastal America, including essential supplies like clothing, food, artillery, medicine, and occasionally, reinforcements.

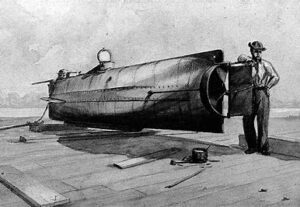

As the United States Navy was constructing its first submarine, the USS Alligator, in late 1861, the Confederacy was also developing their own. Driven by a deep loyalty to the Confederate states and recognizing the potential financial benefits of sinking enemy ships, Horace Hunley, James McClintock (the designer), and Baxter Watson constructed the Pioneer. It underwent testing in the Mississippi River in February 1862 and was later moved to Lake Pontchartrain for further trials. The Union’s approach towards New Orleans led the team to halt development, and the Pioneer was scuttled in the following month. McClintock acknowledged the potential of a boat that could navigate freely at any depth, yet he believed improvements were necessary. The team, including Hunley, Watson, and McClintock, relocated to Mobile to work on a second submarine, the American Diver, in collaboration with Thomas Park and Thomas Lyons of Park and Lyons machine shops. The Confederate States Army supported their efforts, with Lieutenant William Alexander of the 21st Alabama Infantry Regiment overseeing the project. The builders tried various propulsion methods, including McClintock’s electromagnetic drive and a custom steam engine, but ultimately chose a hand-cranked system to avoid the excessive time and cost of more complex engines. By January 1863, the American Diver was ready for harbor trials, but its slow speed rendered it impractical. Despite this, an attack on the Union blockade was attempted by towing the submarine to Fort Morgan. Unfortunately, the submarine was lost to the turbulent waters and strong currents at the entrance of Mobile Bay during bad weather. The crew managed to escape, but the vessel was not retrieved.

The third submarine was the one that was eventually launched. The H.L. Hunley, also known as the CSS H.L. Hunley, played a minor role in the American Civil War. The Hunley demonstrated both the potential and perils of underwater combat. It became the first combat submarine to sink an enemy warship when it sunk the USS Housatonic. However, the Hunley was not fully submerged during the attack and was lost with all hands before it could return to base. Throughout its brief service, the Hunley sank three times, resulting in the deaths of twenty-one crewmen. The submarine was named after its inventor, Horace Lawson Hunley, and was commandeered by the Confederate States Army in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Hunley, measuring nearly 40 feet in length, was constructed in Mobile, Alabama, and set afloat in July 1863. Subsequently, it was transported via rail to Charleston on August 12, 1863. Initially known as the “fish boat,” “fish torpedo boat,” or “porpoise,” the Hunley first sank during a trial run on August 29, 1863, resulting in the death of five crew members. Tragically, it sank once more on October 15, 1863, claiming the lives of all eight crew members, including Horace Lawson Hunley, who was on board despite not being part of the Confederate military. After each incident, the Hunley was recovered and restored to service…until February 17, 1864, that is. That day, the Hunley attacked and sank the 1,240-ton United States Navy screw sloop-of-war Housatonic, which had been on Union blockade-duty in Charleston’s outer harbor. Again, the Hunley didn’t survive the attack, taking all eight members of the third crew with it. This time, the Hunley was also lost.

For years, the Hunley lay at the bottom of the harbor, but she was finally located in 1995. The Hunley was

recovered in 2000 and is exhibited at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, located on the Cooper River in North Charleston, South Carolina. A 2012 examination of the artifacts retrieved from the Hunley indicated that the submarine was approximately 20 feet from its target, the Housatonic, when the torpedo it had deployed detonated, leading also to the submarine’s demise.

recovered in 2000 and is exhibited at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, located on the Cooper River in North Charleston, South Carolina. A 2012 examination of the artifacts retrieved from the Hunley indicated that the submarine was approximately 20 feet from its target, the Housatonic, when the torpedo it had deployed detonated, leading also to the submarine’s demise.

My nephew, Allen Beach has led an interesting life. As a child, his family moved several times, giving him the ability to live in several states. After graduation, Allen joined the United States Navy, and became a corpsman. After his training, he was stationed at Bethesda, Maryland at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, where he cared for, among others, the President of the United States.

My nephew, Allen Beach has led an interesting life. As a child, his family moved several times, giving him the ability to live in several states. After graduation, Allen joined the United States Navy, and became a corpsman. After his training, he was stationed at Bethesda, Maryland at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, where he cared for, among others, the President of the United States.

Following his time at Walter Reed, Allen was stationed in Japan. I think that of all his travels, it was this period that was his favorite. It was there that he met his wife, Gaby, who  changed his life forever. Gaby was also in the United States Navy. He was immediately taken with her, and they soon became an item. Eventually, Allen took Gaby on a trip to Bali, where he proposed, and she accepted. Allen felt complete, but their travels were not over.

changed his life forever. Gaby was also in the United States Navy. He was immediately taken with her, and they soon became an item. Eventually, Allen took Gaby on a trip to Bali, where he proposed, and she accepted. Allen felt complete, but their travels were not over.

Allen and Gaby moved back to Bethesda, Maryland, where both of them finished their Navy time, and began their college educations. After Allen finished his college, with a degree in hospital administration, and Gaby had decided on Nursing, the time had come to move again. This move to a place where Gaby could get into a good nursing program. It was this move that surprised our whole family the most. Gaby looked around, and found  that the nursing program right here in Casper, Wyoming, where most of Allen’s family lives, was the best one. So they moved to Casper. It was a good decision for Allen too, because with his degree and his skills, he was quickly grabbed by Wyoming Medical Center to work in administration there. Allen is the department manager over the referral and communications departments. Allen loves his job, and of course, his family all hope that they will stay here in Casper after Gaby’s college is over. We have really enjoyed having them here, close to the family, after so much of his life was spent so far away from us. Today is Allen’s birthday. Happy birthday Allen!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

that the nursing program right here in Casper, Wyoming, where most of Allen’s family lives, was the best one. So they moved to Casper. It was a good decision for Allen too, because with his degree and his skills, he was quickly grabbed by Wyoming Medical Center to work in administration there. Allen is the department manager over the referral and communications departments. Allen loves his job, and of course, his family all hope that they will stay here in Casper after Gaby’s college is over. We have really enjoyed having them here, close to the family, after so much of his life was spent so far away from us. Today is Allen’s birthday. Happy birthday Allen!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

The morning of December 6, 1945 found the United States Navy desperately searching the area known as the Bermuda Triangle for a group of planes. Flight 19 was a routine navigation and combat training exercise in TBM-type aircraft. The group had set out on December 5, 1945 at 2:10pm from Fort Lauderdale Naval Air Station. Their training would take them due east toward the Bermuda Triangle. Much mystery has surrounded the Bermuda Triangle, with ship and planes alike reporting navigation problems in the area, and some disappearing forever. I don’t exactly know what I believe about the Bermuda Triangle, but it is my opinion that there is a logical explanation for the events that have taken place there. Still, many of the lost planes and ship were never heard from again, and never located, so I don’t know.

The morning of December 6, 1945 found the United States Navy desperately searching the area known as the Bermuda Triangle for a group of planes. Flight 19 was a routine navigation and combat training exercise in TBM-type aircraft. The group had set out on December 5, 1945 at 2:10pm from Fort Lauderdale Naval Air Station. Their training would take them due east toward the Bermuda Triangle. Much mystery has surrounded the Bermuda Triangle, with ship and planes alike reporting navigation problems in the area, and some disappearing forever. I don’t exactly know what I believe about the Bermuda Triangle, but it is my opinion that there is a logical explanation for the events that have taken place there. Still, many of the lost planes and ship were never heard from again, and never located, so I don’t know.

Flight 19 consisted of five TBM Avenger torpedo bombers, all of which disappeared on December 5, 1945, during the overwater navigation training flight from Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale, Florida. In all, 14 airmen on the flight were lost, as were all 13 crew members of a PBM Mariner flying boat that was searching for the planes. It is assumed by professional investigators to have exploded in mid-air. Navy investigators could not determine the cause of the loss of Flight 19, but said the aircraft may have become disoriented and ditched in rough seas after running out of fuel. While that is logical, no debris was ever found, nor were the planes ever located, although some think they know where the planes are these days.

The assignment was called “Navigation problem No. 1,” which seems ironic in retrospect. The name was given before the planes experienced problems. “Navigation problem No. 1” was a combination of bombing and navigation, which other flights had completed or were scheduled to undertake that day. The leader for Flight 19 was United States Navy Lieutenant Charles Carroll Taylor who had about 2,500 flying hours, mostly in aircraft of this type, while his trainee pilots had 300 total, and 60 flight hours in the Avenger. Taylor had recently arrived from Naval Air Station Miami where he had also been a VTB instructor. The student pilots had recently completed other training missions in the area where the flight was to take place. They were United States Marine Captains Edward Joseph Powers and George William Stivers, United States Marine Second Lieutenant Forrest James Gerber and United States Navy Ensign Joseph Tipton Bossi. The callsigns for the flight started with ‘Fox Tair,’ or FT and the plane number.

Each aircraft was fully fueled, and during pre-flight checks it was discovered they were all missing clocks. Navigation of the route was intended to teach dead reckoning principles, which involved calculating among other things elapsed time. I suppose that if trained, a person could do that, but I don’t think I could. The apparent lack of timekeeping equipment was not a cause for concern as it was assumed each man had his own watch. Takeoff was scheduled for 13:45 local military time, but the late arrival of Taylor delayed departure until 14:10. The weather at NAS Fort Lauderdale was described as “favorable, sea state moderate to rough.” Taylor was supervising the mission, and a trainee pilot had the role of leader out front.

This exercise was called “Naval Air Station, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, navigation problem No. 1,” and involved three different legs. There should have actually been four flown. After take off, the planes flew on heading 091°, which is almost due east for 56 nautical miles, until they reached Hen and Chickens Shoals where low level bombing practice was carried out. The flight was to continue on that heading for another 67 nautical miles before turning onto a course of 346° for 73 nautical miles, in the process over-flying Grand Bahama island. The next scheduled turn was to a heading of 241° to fly 120 nautical miles at the end of which the exercise was completed and the Avengers turned left to return to NAS Fort Lauderdale.

Radio conversations between the pilots were overheard by base and other aircraft in the area. The practice bombing operation was carried out because at about 15:00 a pilot requested and was given permission to drop his last bomb. Forty minutes later thins began to go wrong, when another flight instructor, Lieutenant Robert F. Cox in FT-74, forming up with his group of students for the same mission, received an unidentified transmission. An unidentified crew member asked Powers, one of the students, for his compass reading. Powers replied: “I don’t know where we are. We must have got lost after that last turn.” Cox then transmitted; “This is FT-74, plane or boat calling ‘Powers’ please identify yourself so someone can help you.” The response after a few moments was a request from the others in the flight for suggestions. FT-74 tried again and a man identified as FT-28 (Taylor) came on. “FT-28, this is FT-74, what is your trouble?” “Both of my compasses are out”, Taylor replied, “and I am trying to find Fort Lauderdale, Florida. I am over land but it’s broken. I am sure I’m in the Keys but I don’t know how far down and I don’t know how to get to Fort Lauderdale.” As the weather deteriorated, radio contact became intermittent, and it was believed that the five aircraft were actually by that time more than 200 nautical miles out to sea east of the Florida peninsula. Taylor radioed “We’ll fly 270 degrees west until landfall or running out of gas.” The last known location of Flight 19 was 75 miles northeast of Cocoa, Florida.

Had Flight 19 actually been where Taylor believed it to be, landfall with the Florida coastline would have been reached in a matter of 10 to 20 minutes or less, depending on how far down they were. However, a later reconstruction of the incident showed that the islands visible to Taylor were probably the Bahamas, well northeast of the Keys, and that Flight 19 was exactly where it should have been. The board of investigation found that because of his belief that he was on a base course toward Florida, Taylor actually guided the flight further northeast and out to sea. The only problem I have with that idea is that they never found any debris, and never located the planes. Had they crashed into the ocean, they should have shown up somewhere.

In 1986, the wreckage of an Avenger was found off the Florida coast during the search for the wreckage of the Space Shuttle Challenger. Aviation archaeologist Jon Myhre raised the wreck from the ocean floor in 1990. He was convinced it was one of the missing planes, but positive identification could not be made. In 1991, the wreckage of five Avengers was discovered off the coast of Florida, but engine serial numbers revealed they  were not Flight 19. They had crashed on five different days all within 1.5 miles of each other. Records revealed that the various discovered aircraft, including the group of five, were declared either unfit for maintenance/repair or obsolete, and were simply disposed of at sea. Records also showed training accidents between 1942 and 1945 accounted for the loss of 95 aviation personnel from NAS Fort Lauderdale. In 1992, another expedition located scattered debris on the ocean floor, but nothing could be identified. In the last decade, searchers have been expanding their area to include farther east, into the Atlantic Ocean, but the remains of Flight 19 have still never been confirmed found.

were not Flight 19. They had crashed on five different days all within 1.5 miles of each other. Records revealed that the various discovered aircraft, including the group of five, were declared either unfit for maintenance/repair or obsolete, and were simply disposed of at sea. Records also showed training accidents between 1942 and 1945 accounted for the loss of 95 aviation personnel from NAS Fort Lauderdale. In 1992, another expedition located scattered debris on the ocean floor, but nothing could be identified. In the last decade, searchers have been expanding their area to include farther east, into the Atlantic Ocean, but the remains of Flight 19 have still never been confirmed found.

I always knew that my uncle, George Hushman served in the United States Navy during World War II, but like many of the men who fight in wars, discussing what happened during their deployment is something that few want to talk about. My family spent quite a bit of time with Uncle George and Aunt Evelyn, who was my mom’s sister, and their family, but in all those visits, I never heard my dad, Allen Spencer, or my Uncle George ever talk about their time in the war. In fact, had it not been for an old picture of the two couples going to the Military Ball, I don’t think I would have even known what branch of the military Uncle George was in.

I always knew that my uncle, George Hushman served in the United States Navy during World War II, but like many of the men who fight in wars, discussing what happened during their deployment is something that few want to talk about. My family spent quite a bit of time with Uncle George and Aunt Evelyn, who was my mom’s sister, and their family, but in all those visits, I never heard my dad, Allen Spencer, or my Uncle George ever talk about their time in the war. In fact, had it not been for an old picture of the two couples going to the Military Ball, I don’t think I would have even known what branch of the military Uncle George was in.

Recently, while researching my family history, I came across some Muster Rolls for the United States Navy, for one USS Gurke. The USS Gurke was a DD Type destroyer whose mission was to provide anti-submarine and anti-surface defense to other surface forces. The Gurke is one of 103 Gearing Class destroyers that were built at 8 different shipyards. It was originally laid down as USS John A. Bole in October of 1944, but was renamed USS Henry Gurke (DD-783) prior to her launching on February 15, 1945 at the Todd-Pacific Shipyards, Inc, in Tacoma, Washington. The ship’s sponsor was Mrs. Julius Gurke, mother of Private Gurke, for whom the ship was named. The destroyer was commissioned 12 May 1945, under the command of Commander  Kenneth Loveland. It was to this ship that my Uncle George was assigned beginning May 12, 1945. Prior to that he had been a S2c V6 on the USS LCI (G) 23, which was a transport ship.

Kenneth Loveland. It was to this ship that my Uncle George was assigned beginning May 12, 1945. Prior to that he had been a S2c V6 on the USS LCI (G) 23, which was a transport ship.

On the Gurke, Uncle George had a rating of S1c V6. I wasn’t sure what that meant, but I’m sure that any navy veteran would know. A V6 is a person who volunteered in World War II. As a V6 they had to be discharged by six months after the war was over. An S1c was a seamen first class. So now I knew what my uncle did during the war. Seaman first class was the rank right below a Petty Officer. The Seaman did a variety of jobs onboard the ship and could have worked anywhere on the ship. I suppose it would be a rank similar to the private, or in non-military verbiage, a laborer. That was the rank that many men went into the navy with, but a seaman first class was no longer a trainee. He had been trained to do his duties, and didn’t have to be told.

After a shakedown along the West Coast, the Gurke sailed for the Western Pacific August 27, 1945, reaching  Pearl Harbor on September 2nd. From there she continued west to participate in the occupation of Japan and former Japanese possessions. Returning to home port of San Diego, in February 1946, the Gurke participated in training operations until September 4, 1947, when she sailed for another WestPac cruise. Two further WestPac cruises, alternating with operations out of San Diego, and a cruise to Alaska in 1948 aiding the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Yukon gold rush, filled Gurke’s schedule until the outbreak of the Korean War. Of course, I assume that upon Gurke’s return to her home port of San Diego, my uncle was either assigned to another ship, was at home port, or discharged. I am very proud of his service. Today is Uncle George’s 93rd birthday. Happy birthday Uncle George!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

Pearl Harbor on September 2nd. From there she continued west to participate in the occupation of Japan and former Japanese possessions. Returning to home port of San Diego, in February 1946, the Gurke participated in training operations until September 4, 1947, when she sailed for another WestPac cruise. Two further WestPac cruises, alternating with operations out of San Diego, and a cruise to Alaska in 1948 aiding the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Yukon gold rush, filled Gurke’s schedule until the outbreak of the Korean War. Of course, I assume that upon Gurke’s return to her home port of San Diego, my uncle was either assigned to another ship, was at home port, or discharged. I am very proud of his service. Today is Uncle George’s 93rd birthday. Happy birthday Uncle George!! Have a great day!! We love you!!

I think most of us have heard of the Hindenburg…the hydrogen filled blimp like airship the crashed in a ball of fire on May 6, 1937, bringing with it a loss of 36 lives…amazing when you consider that there were 97 people on board when that ball of fire crashed. What many people may not know is that the Hindenburg was not the only hydrogen powered airship. The USS Macon (ARS-5), named for Macon, Georgia and operated by the United States Navy for scouting and served as a “flying aircraft carrier” as well. It was designed to carry biplane parasite aircraft. Macon held single seat Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawks for scouting or two seat Fleet N2Y-1 for training. The Macon was a little under 20 feet shorter than the Hindenburg. The USS Macon also had a sister ship…the USS Akron (ARS-4).

I think most of us have heard of the Hindenburg…the hydrogen filled blimp like airship the crashed in a ball of fire on May 6, 1937, bringing with it a loss of 36 lives…amazing when you consider that there were 97 people on board when that ball of fire crashed. What many people may not know is that the Hindenburg was not the only hydrogen powered airship. The USS Macon (ARS-5), named for Macon, Georgia and operated by the United States Navy for scouting and served as a “flying aircraft carrier” as well. It was designed to carry biplane parasite aircraft. Macon held single seat Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawks for scouting or two seat Fleet N2Y-1 for training. The Macon was a little under 20 feet shorter than the Hindenburg. The USS Macon also had a sister ship…the USS Akron (ARS-4).

The USS Macon was in service less than two years, when on February 12, 1935 it was damaged in a storm and crashed off California’s Big Sur coast. Most of the crew was saved, and the wreckage remains on the ocean floor. The site of the wreckage remains on the United States National Register of Historic Places. I find myself interested in things like shipwrecks and plane crashes, but the ones underwater are especially interesting, because they are so inaccessible to most people. The USS Macon, like the Hindenburg proved not to be the best choice of an airship. There were really to many conditions that could easily bring them down. And the fact that they contained so much helium made then a flying bomb, in all reality. I don’t suppose that was something they considered when making these machines, but I’m sure it later became the reason that they discontinues this type of airship. I find it quite sad that it too two crashes to realize that they were not the safest way to fly.

I suppose they served their purpose though. I think it’s amazing that they could actually carry a plane on a hook and let it take off from the air. Launching and recovery from the airship in flight was done using a skyhook. The Sparrowhawk had a hook mounted above its top wing that attached to the cross-bar of a trapeze mounted on the carrier airship. For launching, the trapeze was lowered clear of the hull into the moving airship’s slipstream. With engine running, the Sparrowhawk would then disengage its hook and fall away from the airship. For recovery, the biplane would fly underneath the airship, until it was beneath the trapeze. The

pilot would climb up from below, and hook onto the cross-bar. Once the Sparrowhawk was secure, it could be hoisted by the trapeze back within the airship’s hull, the engine was cut as it passed the hangar door. To me, this seems like a tricky maneuver, but the pilots soon learned the technique and said it was much easier than landing on a moving aircraft carrier. Soon, the pilots acquired the nickname “The men on the Flying Trapeze” and their aircraft were decorated with appropriate emblems. Now to me…that is cool!!

pilot would climb up from below, and hook onto the cross-bar. Once the Sparrowhawk was secure, it could be hoisted by the trapeze back within the airship’s hull, the engine was cut as it passed the hangar door. To me, this seems like a tricky maneuver, but the pilots soon learned the technique and said it was much easier than landing on a moving aircraft carrier. Soon, the pilots acquired the nickname “The men on the Flying Trapeze” and their aircraft were decorated with appropriate emblems. Now to me…that is cool!!