united states congress

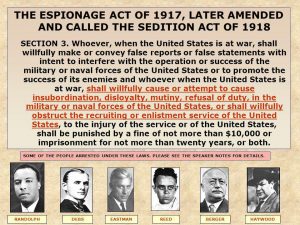

It seems strange to me to create a piece of legislation that protects the government and the war effort from…basically hate speech, but on May 16, 1918, the United States Congress did pass just such an act. What seems even more strange is to have a need for such a piece of legislation during a time of war. Called the Sedition Act, a piece of legislation designed to protect America’s participation in World War I. Along with the Espionage Act of the previous year, the Sedition Act was orchestrated largely by A. Mitchell Palmer, the United States attorney general under President Woodrow Wilson. I think most of us understand espionage, and why such an act was important to the war effort. The Espionage Act, passed shortly after the US entrance into the war in early April 1917, made it a crime for any person to convey information intended to interfere with the U.S. armed forces’ prosecution of the war effort or to promote the success of the country’s enemies.

It seems strange to me to create a piece of legislation that protects the government and the war effort from…basically hate speech, but on May 16, 1918, the United States Congress did pass just such an act. What seems even more strange is to have a need for such a piece of legislation during a time of war. Called the Sedition Act, a piece of legislation designed to protect America’s participation in World War I. Along with the Espionage Act of the previous year, the Sedition Act was orchestrated largely by A. Mitchell Palmer, the United States attorney general under President Woodrow Wilson. I think most of us understand espionage, and why such an act was important to the war effort. The Espionage Act, passed shortly after the US entrance into the war in early April 1917, made it a crime for any person to convey information intended to interfere with the U.S. armed forces’ prosecution of the war effort or to promote the success of the country’s enemies.

The Sedition Act was aimed at socialists, pacifists and other anti-war activists. The Act imposed harsh penalties on anyone who was found guilty of making false statements that interfered with the prosecution of the war; insulting or abusing the United States government, the flag, the Constitution or the military; agitating against the production of necessary war materials; or advocating, teaching or defending any of these acts. Hmmm…I think we have need of this act in today’s America. Those who were found guilty of such actions, would according to the Sedition Act be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both. The penalty was the same as the one for acts of espionage in the earlier legislation.

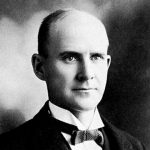

Though Wilson and Congress considered the Sedition Act as crucial in order to stifle the spread of dissent within the country in that time of war, modern legal scholars felt the act was contrary to the letter and spirit of the US Constitution, specifically to the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights. One of the most famous prosecutions under the Sedition Act during World War I was that of Eugene V. Debs, a pacifist labor organizer and founder of the International Workers of the World (IWW Debs had run for president in 1900 as a Social Democrat and in 1904, 1908 and 1912 on the Socialist Party of America ticket. He delivered an anti-war speech in June 1918 in Canton, Ohio and was promptly arrested. After being found guilty, he was sentenced to ten years in prison under the Sedition Act. Debs appealed the decision and upon stating that Debs had acted with the intention of obstructing the war effort the US Supreme Court upheld his conviction.

Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes referred to the earlier landmark case of Schenck v. United States (1919) as the basis for his decision. Charles Schenck, also a Socialist, had been found guilty under the Espionage Act after distributing a flyer urging recently drafted men to oppose the United States conscription policy. Holmes stated that freedom of speech and press could be constrained in certain instances. He said that the question in every case is “whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.”

Debs’ sentence was commuted in 1921 when the Sedition Act was repealed by Congress. Major portions of the Espionage Act remain part of United States law to the present day, although the crime of sedition was largely eliminated by the famous libel case Sullivan v. New York Times (1964), which determined that “the press’s criticism of public officials—unless a plaintiff could prove that the statements were made maliciously or with reckless disregard for the truth—was protected speech under the First Amendment.”