United States

When a president leaves office these days, they leave with a lifetime pension, but until 1958, when a president left office, he was not afforded any compensation. That meant that after their time in office, they had to go back to earning a living on their own again. I understand that our presidents have a really big job, but the longest they can be in that office is eight years, so a lifelong pension doesn’t totally make sense to me, but that is clearly another story.

When a president leaves office these days, they leave with a lifetime pension, but until 1958, when a president left office, he was not afforded any compensation. That meant that after their time in office, they had to go back to earning a living on their own again. I understand that our presidents have a really big job, but the longest they can be in that office is eight years, so a lifelong pension doesn’t totally make sense to me, but that is clearly another story.

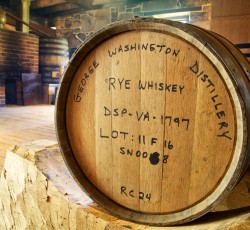

After his term in office, our very first president, George Washington, was approached by James Anderson in 1797, who urged him to open a whiskey distillery. Anderson, who had experience distilling grain in Scotland and Virginia, told Washington that Mount Vernon’s crops, combined with the large merchant gristmill and the abundant water supply, would make a whiskey distillery a very profitable venture, So, after his term, Washington opened that whiskey distillery. By 1799, his distillery was the largest in the country, producing 11,000 gallons of un-aged whiskey!

By the 1810 census, distilleries were quite commonplace in the United States. In fact, there were more than 3,600 operating in Virginia alone, but George Washington’s distillery was one of the largest in the nation at that time, measuring 75 x 30 feet, or 2,250 square feet as opposed to the average being 800 square feet.

George Washington’s whiskey was not bottled, branded, or barrel-aged like most whiskeys of that time. Instead, his was put in an uncharred barrel, which was usually 30 gallons in size. It was then sent into Alexandria, where it was consumed right away as an unaged whiskey. This process brought a hefty stream of cash to Mount Vernon. Not only did George Washington earn his own living, but he also paid taxes on his income. He left office and became a normal everyday citizen again.

George Washington’s Mount Vernon still produces limited batches of both aged and unaged whiskey today. These days, however, the whiskey is placed in branded bottles. It is, nevertheless, produced in the traditional

18th-century way as it was before, in George Washington’s reconstructed distillery, proving yet again that if a president was resourceful, he is unlikely to need a lifelong pension for eight years of work. I have a lot of respect for such a resourceful man like George Washington was. He didn’t expect the American people to carry his lifestyle on their backs for the rest of his life.

18th-century way as it was before, in George Washington’s reconstructed distillery, proving yet again that if a president was resourceful, he is unlikely to need a lifelong pension for eight years of work. I have a lot of respect for such a resourceful man like George Washington was. He didn’t expect the American people to carry his lifestyle on their backs for the rest of his life.

It is a tradition in the United States, that every four years on January 20, there is a transition of power. The incoming president is sworn in and afterward, the outgoing president leaves the White House…or sometimes the outgoing president leaves before the swearing in of the new president. Unfortunately, not every transition is an amiable one or even a peaceful one. I suppose that is because neither side likes to lose. In fact, when the opposing party takes over the White House these days, it usually isn’t a peaceful transition. Often there are protesters and sometimes things get out of hand…and of course, there is plenty of blame to go around. The truth is often very obscured, and the blame is laid on the wrong party. You can like what I say, or not, but the reality is that there is plenty of proof concerning the January 6th event of 2021, and the wrong people were accused.

It is a tradition in the United States, that every four years on January 20, there is a transition of power. The incoming president is sworn in and afterward, the outgoing president leaves the White House…or sometimes the outgoing president leaves before the swearing in of the new president. Unfortunately, not every transition is an amiable one or even a peaceful one. I suppose that is because neither side likes to lose. In fact, when the opposing party takes over the White House these days, it usually isn’t a peaceful transition. Often there are protesters and sometimes things get out of hand…and of course, there is plenty of blame to go around. The truth is often very obscured, and the blame is laid on the wrong party. You can like what I say, or not, but the reality is that there is plenty of proof concerning the January 6th event of 2021, and the wrong people were accused.

We all have our own opinion on the 2020 election, and I won’t dispute that or its outcome, but now the people of this nation have spoken…again, in a truly fair election, and we are about to put President Donald J Trump back in the White House. The transition actually began when he won the United States presidential election on November 5, 2024, becoming the president-elect. Because of our system, his formal election came when the Electoral College voted on December 17, 2024. The results were certified by a joint of Congress on January 6, 2025, and the transition is scheduled to conclude with Trump’s inauguration on January 20, 2025.

I think this country is so ready for the changes President Trump will bring back. His first term in office showed  the people just how prosperous the country could be. We were almost energy independent; gas prices were low, patriotism was high, and things made sense. All that went away when Biden took office. It was as if the whole country went crazy. Now that President Trump is coming back, things are turning around so quickly that it is awe inspiring. The whole feel of things in this country is taking a 180° turn…overnight. It is amazing. The people he has chosen for his cabinet totally add to the air of excitement. And of course, we are very excited with his vice-presidential choice. Vice President JD Vance came up from poor roots, but worked hard to make something of himself, and I think he will be an amazing vice president. This president will bring back common sense.

the people just how prosperous the country could be. We were almost energy independent; gas prices were low, patriotism was high, and things made sense. All that went away when Biden took office. It was as if the whole country went crazy. Now that President Trump is coming back, things are turning around so quickly that it is awe inspiring. The whole feel of things in this country is taking a 180° turn…overnight. It is amazing. The people he has chosen for his cabinet totally add to the air of excitement. And of course, we are very excited with his vice-presidential choice. Vice President JD Vance came up from poor roots, but worked hard to make something of himself, and I think he will be an amazing vice president. This president will bring back common sense.

Trump became the presumptive nominee of his party on March 12, 2024, and formally accepted the nomination at the Republican National Convention in July. On August 16th, Trump announced the formation of the transition team with Linda McMahon, Trump’s former head of the Small Business Administration, and Howard Lutnick, the billionaire CEO of Cantor Fitzgerald and BGC Group, officially named as co-chairs. Vice presidential nominee JD Vance, along with sons Donald Jr. and Eric Trump, were designated as honorary co-chairs. The effort beginning at this time was considered unusually late, as historically, most transition efforts start in late spring. Nevertheless, this team is very capable, and they will have everything in readiness. Attorney Robert F Kennedy Jr and former congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard were added as honorary co-chairs on August 27th. Both are former Democrats who had recently endorsed Trump. Kennedy had initially launched an independent presidential campaign before withdrawing to endorse Trump. Kennedy is reportedly in for a Cabinet position in this administration.

Watching the inauguration today felt like the opening of prison doors. The nation has been under such oppression, and negativity. The future seemed hopeless, but all that changed at 12:01pm in the Capitol Rotunda in Washington DC. President Trump outlined the things he plans to do, and with each on, we began to

feel hope again. He is so sharp, and when he sees something that is wrong, he goes after it. He works to correct the problem and repair the situation. President Trump is a very hands-on, go get ’em kind of guy, and he is not politically correct, an action that has had a crippling effect on this nation. With President Trump’s return to the White House comes dignity, hope, patriotism, transparency, honesty, and truthfulness. I say bring it on President Trump. We are ready for you!!

feel hope again. He is so sharp, and when he sees something that is wrong, he goes after it. He works to correct the problem and repair the situation. President Trump is a very hands-on, go get ’em kind of guy, and he is not politically correct, an action that has had a crippling effect on this nation. With President Trump’s return to the White House comes dignity, hope, patriotism, transparency, honesty, and truthfulness. I say bring it on President Trump. We are ready for you!!

The 83rd anniversary of Pearl Harbor, at least for the Baby Boomer generation and older, prompts reflection on the United States’ stance of often waiting for an initial attack before responding. While this is not always the case, it appears to be a common scenario. The US strives to act as a peacemaker, and the decision to go to war is never taken lightly due to the grave consequences of taking lives. Typically, numerous warnings are issued before any action is taken, and frequently, it’s too late to preemptively strike. The first to strike is often labeled the aggressor, but there are times when ample warning signals an imminent attack, yet the response is still delayed, until the attack occurs, resulting in loss of life and leaving the survivors to deal with the aftermath rather than considering an immediate counterstrike. Of course, the reverse is hard to deal with too, because we would come off as being the aggressor, and that just isn’t our style.

The 83rd anniversary of Pearl Harbor, at least for the Baby Boomer generation and older, prompts reflection on the United States’ stance of often waiting for an initial attack before responding. While this is not always the case, it appears to be a common scenario. The US strives to act as a peacemaker, and the decision to go to war is never taken lightly due to the grave consequences of taking lives. Typically, numerous warnings are issued before any action is taken, and frequently, it’s too late to preemptively strike. The first to strike is often labeled the aggressor, but there are times when ample warning signals an imminent attack, yet the response is still delayed, until the attack occurs, resulting in loss of life and leaving the survivors to deal with the aftermath rather than considering an immediate counterstrike. Of course, the reverse is hard to deal with too, because we would come off as being the aggressor, and that just isn’t our style.

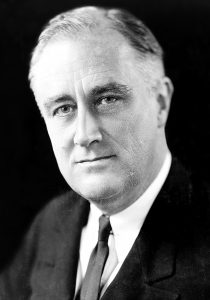

On December 7, 1941, the United States found itself in a precarious position. Despite repeatedly warning Japan, the United States using the Hull Note as a show of the ultimate caution, tried to avoid entering World War II. The Hull Note officially the Outline of Proposed Basis for Agreement Between the United States and Japan, was the final proposal delivered to the Empire of Japan by the United States of America before the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) and the Japanese declaration of war (seven and a half hours after the attack began). Unfortunately, Japan to all that as a show of weakness. Nevertheless, knowing that Japan would likely not comply, and essentially declaring war, the US still hoped they would proceed slowly, perhaps  even reconsider their course. Conversely, Japan acted swiftly, dispatching their strike force towards Pearl Harbor and simultaneously sending a decoy towards Thailand to mislead the US. Then, believing an attack on Thailand was imminent, President Roosevelt implored Emperor Hirohito via telegram to act “for the sake of humanity” and prevent further devastation. The US endeavored to maintain peace.

even reconsider their course. Conversely, Japan acted swiftly, dispatching their strike force towards Pearl Harbor and simultaneously sending a decoy towards Thailand to mislead the US. Then, believing an attack on Thailand was imminent, President Roosevelt implored Emperor Hirohito via telegram to act “for the sake of humanity” and prevent further devastation. The US endeavored to maintain peace.

After transmitting the telegram, President Roosevelt was working on his stamp collection alongside his personal advisor, Harry Hopkins. They deliberated over Japan’s rejection of the Hull Note. Hopkins proposed a preemptive strike by America, but President Roosevelt maintained that it was not an option. Unbeknownst to them, it was already too late for a first strike…time had run out. The Japanese forces were en route to Pearl Harbor, where a significant segment of the Pacific Fleet lay anchored, vulnerable to attack. The impending ambush would devastate 18 US ships, including the Arizona, Virginia, California, Nevada, and West Virginia, either destroyed, sunk, or capsized. Over 180 aircraft were destroyed on the ground, with an additional 150 damaged, leaving a mere 43 operational. American casualties exceeded 3,400, with over 2,400 fatalities—1,000 of which occurred on the Arizona alone. The Japanese incurred fewer than 100 losses.

It often appears that the party who strikes first, swiftly and with the element of surprise, ultimately fares better. The side caught off guard, or the one that ignored the warning signs, is usually defeated. With one of the strongest military forces on Earth, America should not be taken by surprise. I believe that overconfidence in one’s strength, leading to a lack of vigilance, can result in the downfall of even the mightiest. The United States has been such a force, but our reluctance to preemptively strike seems to invite repeated attacks without warning. It is only after such attacks that we seem to retaliate.

It’s indeed a dilemma, perhaps reflective of President Roosevelt’s perspective. If we strike first, we’re vilified globally as the aggressors, akin to those at Pearl Harbor. If we don’t, we face condemnation from our own citizens. Moreover, our intelligence isn’t infallible, leading to situations like the surprise attack on December 7th, 1941, when we expected honor from an adversary who did not feel bound by it. It seems that although being

attacked unprovoked is undesirable, we must still act honorably and not launch a preemptive strike merely based on anticipated aggression. Otherwise, we become indistinguishable from those nations we confront in war for their acts of invasion. Nevertheless, it remains a huge challenge to always be the nation that does the right things, especially when there is a profound mistrust of our enemies…because we know better.

attacked unprovoked is undesirable, we must still act honorably and not launch a preemptive strike merely based on anticipated aggression. Otherwise, we become indistinguishable from those nations we confront in war for their acts of invasion. Nevertheless, it remains a huge challenge to always be the nation that does the right things, especially when there is a profound mistrust of our enemies…because we know better.

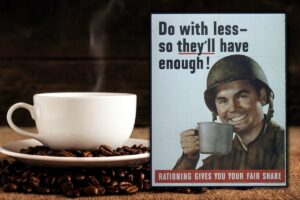

War usually brings with it, shortages and rationing. On November 29, 1942, coffee was added to the list of rationed items in the United States. Now, people can live without some things, but I would think that coffee would be a really hard item to add to that list. The coffee production in Latin America was at a record, but it made no difference, the increasing demand from military and civilian sectors, along with the pressing needs of shipping for other wartime efforts, necessitated the restriction of its availability.

War usually brings with it, shortages and rationing. On November 29, 1942, coffee was added to the list of rationed items in the United States. Now, people can live without some things, but I would think that coffee would be a really hard item to add to that list. The coffee production in Latin America was at a record, but it made no difference, the increasing demand from military and civilian sectors, along with the pressing needs of shipping for other wartime efforts, necessitated the restriction of its availability.

The truth is that scarcity or shortages were seldom the cause of rationing during the war. Rationing was typically implemented for two main reasons…to ensure an equitable distribution of resources and food to all citizens and to prioritize military needs for certain raw materials in light of the current emergency.

At first, the restriction on the use of certain items was voluntary. People were simply asked to cut back. The problem is that voluntary cutting back seldom works. Also, President Roosevelt initiated “scrap drives” to collect discarded rubber items like old garden hoses, tires, and bathing caps, especially after Japan seized the Dutch East Indies, a key rubber supplier for the United States. These collected items could be exchanged at gas stations for a penny per pound. In the early stages of the war, patriotism and the eagerness to support the war effort was enough.

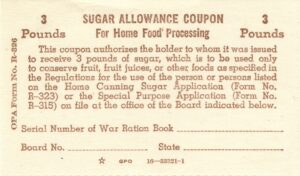

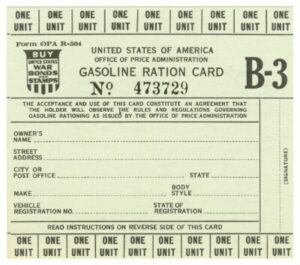

As US shipping, including oil tankers, became increasingly susceptible to German U-boat attacks, gasoline was the first commodity to be rationed. In seventeen eastern states, car owners were limited to three gallons of gasoline weekly beginning in May 1942. By year’s end, rationing had expanded nationwide, with drivers required to affix ration stamps to their car windshields. Things like butter, were reserved for military use, and so were also rationed. Also limited were coffee, sugar, and milk. In fact, approximately one-third of all food typically consumed by civilians was rationed during the war at some point. We had to make sure our troops had what they needed. They were fighting for our freedom, and we would sacrifice so they could have

what they needed. The American people were determined and willing. Of course, that didn’t stop the black market from becoming a source for rationed items, selling goods at prices above those set by the Office of Price Administration to Americans who could afford the marked-up costs. Nevertheless, certain items were removed from the rationing list ahead of time; coffee became available in July 1943, but sugar remained rationed until June 1947.

what they needed. The American people were determined and willing. Of course, that didn’t stop the black market from becoming a source for rationed items, selling goods at prices above those set by the Office of Price Administration to Americans who could afford the marked-up costs. Nevertheless, certain items were removed from the rationing list ahead of time; coffee became available in July 1943, but sugar remained rationed until June 1947.

As with any attack, planning must be done before any action can take place. The attack on Pearl Harbor was no exception. A little more than a month, on November 5, 1941, the Combined Japanese Fleet received Top-Secret Order Number 1, stating that in just over a month, Pearl Harbor, along with Malaya (now Malaysia), the Dutch East Indies, and the Philippines, was to be bombed. There was much preparation to do, and very little time to do it. Failure would not be an option, because failure would mean death, and in fact, the battle was a planned death for the kamikaze pilots.

As with any attack, planning must be done before any action can take place. The attack on Pearl Harbor was no exception. A little more than a month, on November 5, 1941, the Combined Japanese Fleet received Top-Secret Order Number 1, stating that in just over a month, Pearl Harbor, along with Malaya (now Malaysia), the Dutch East Indies, and the Philippines, was to be bombed. There was much preparation to do, and very little time to do it. Failure would not be an option, because failure would mean death, and in fact, the battle was a planned death for the kamikaze pilots.

The problem was that the relationship between the United States and Japan had rapidly worsened following Japan’s occupation of Indochina in 1940 and the subsequent threat to the Philippines, which is an American territory. With the seizure of the Cam Ranh naval base, located roughly 800 miles from Manila, something had to be dome. In response, the United States seized all Japanese assets within its borders and shut the Panama Canal to Japanese shipping. In September 1941, President Roosevelt, with a statement prepared by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, warned that the United States would go to war with Japan if it continued to invade territories in Southeast Asia or the South Pacific. The United States hoped, and yes even expected the Japanese to comply.

Nevertheless, despite ongoing negotiations between the United States Secretary of State and his Japanese counterpart to alleviate tensions, Hideki Tojo, the War Minister soon to become Prime Minister, was not inclined to retreat from occupied territories. Viewing the American “threat” of war as an ultimatum, he readied to initiate the first strike in a confrontation with the United States…the attack on Pearl Harbor.

We all know what happened next, but could it have been prevented? I don’t believe that Japan had any interest in preventing a war with the United States. So, it would have been up to the United States to pave the way for peace between the two countries…if that was even possible. Since I don’t believe it was possible, due to Japan’s plans, The other aspect of the question is how America might have prevented Pearl Harbor. It is likely that intelligence shortcomings and underestimation of the Japanese played a role. However, it is argued that the American military hawks and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt may have seen the attack as a necessary catalyst to persuade the nation to enter the war against the tyrannies of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. I don’t know for sure, and I hate to say that was exactly it, but I wonder if they expected the attack to be as bad as it ended up being.

Numerous theories speculate on whether Roosevelt, or even Great Britain’s Winston Churchill, had foreknowledge of the impending attack. However, it seems improbable. Military leaders typically do not permit such attacks due to the unpredictability of the consequences. Consider the possibilities: the attack occurring prematurely and sinking the carriers, the destruction of oil facilities, or the Japanese invasion and occupation of Hawaii. These are risks that no military leader would willingly take, regardless of their desire for a pretext to enter the war. It is probable that Roosevelt anticipated an attack, although the specifics of when and where remained uncertain.

To address the question of how America could have avoided Pearl Harbor, one must dig deeper into history, far beyond the oil embargoes of the early 1940s. It could be argued that the path to Pearl Harbor was set as early as July 8, 1853, when American Commodore Matthew Perry entered Tokyo Bay with his four ships, aiming to reestablish regular trade between Japan and the Western world. It all seemed innocent enough, but while Japan was once receptive to Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch influences. Then, with each nation attempting to introduce Western culture and religion, Japan began to have issues with them. Within a few decades, these Western powers were expelled, leaving only the Dutch with limited trading privileges through Dejima, a small man-made island in Nagasaki.

The Japanese quickly assimilated the practices of their adversaries, which included adopting a Western-trained military. The Army was advised by the French and later the Germans, while the Navy was guided by British advisors and equipped with British-built warships. Japan managed to defeat its long-standing rival China, annexing Taiwan and Korea into its gradually expanding empire. In 1904-1905, Japan, was hardly a regional power a mere fifty years prior, overwhelmed Imperial Russia in a fierce conflict. The victory followed a surprise assault on the Russian Navy at Port Arthur…something that American military planners in 1941 should have taken notice of! The initial attack aimed to incapacitate the Russians, yet the pivotal battle occurred at Tsushima Straits, where Admiral Togo Heihaciro led the Japanese fleet to obliterate eight Russian battleships.

In World War I, which followed less than ten years later, Japan joined with the Russians and aided the British in seizing the German-held Tsingtao in China. Japan also took control of the Marianas, the Caroline Islands, and the Marshall Islands. All this further fueled Japan’s ambitions concerning Chinese territories and the American-

controlled Philippines for potential expansion. Then, came “the straw that broke the camel’s back” for the Americans, and with the threat against the Philippines, the attack of Pearl Harbor was set in motion…all due to the actions taken to protect the Philippines.

controlled Philippines for potential expansion. Then, came “the straw that broke the camel’s back” for the Americans, and with the threat against the Philippines, the attack of Pearl Harbor was set in motion…all due to the actions taken to protect the Philippines.

Had Perry not “opened” Japan, this sequence of events might not have unfolded. This is not to imply Japan would not have modernized, but the trajectory could have been altered. Without the Emperor’s restoration, the Boshin War might not have taken place, possibly preventing the swift military reforms that followed. Of course, all this could be speculation, but the experts think it is fact.

As in most new ventures, there is risk involved, but sometimes it seems like the risk is too much. When the race to put a man in space began, the fight was on between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was a fight that would eventually be won by the Soviet Union…but at what cost. Putting a man in space was going to be a big deal, but no one knew if space was a safe place, or if humans could even survive in space. It was an unusual dilemma, and it needed an unusual solution.

As in most new ventures, there is risk involved, but sometimes it seems like the risk is too much. When the race to put a man in space began, the fight was on between the United States and the Soviet Union. It was a fight that would eventually be won by the Soviet Union…but at what cost. Putting a man in space was going to be a big deal, but no one knew if space was a safe place, or if humans could even survive in space. It was an unusual dilemma, and it needed an unusual solution.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Soviet space program utilized dogs for sub-orbital and orbital space flights to assess the viability of human spaceflight. These dogs, including the first animal in space, named Laika, were used to orbit the Earth, and underwent surgical modifications to collect vital data for human survival in space. The program often selected female dogs for their anatomical fit with the spacesuits and mixed-breed dogs for their perceived resilience, but there was just one problem. The dogs didn’t really understand what was going on, and there was no human to calm them down.

Laika, a part-Siberian Husky, was once a stray wandering the streets of Moscow before being recruited into the Soviet space program. She was used to little human contact. Nevertheless, she got used to it is the space program. While in space, she endured several hours aboard the USSR’s second artificial Earth satellite, sustained by an advanced life-support system. Electrodes connected to her body transmitted vital data to ground scientists about the physiological impacts of spaceflight. I just don’t see how poor Laika could have possibly understood all of this. Unfortunately, Laika died due to overheating and severe emotional stress.

During this period of testing, the Soviet Union conducted missions that included at least 57 dogs as passengers. Several dogs were sent on multiple flights. The majority survived, with most fatalities resulting from technical

failures within the test parameters. Laika was a notable exception, as her death was anticipated during the Sputnik 2 mission orbiting Earth on November 3, 1957.

failures within the test parameters. Laika was a notable exception, as her death was anticipated during the Sputnik 2 mission orbiting Earth on November 3, 1957.

In preparation for the first manned Soviet space mission, over a dozen Russian dogs were sent into space, and unfortunately, at least five died during the flight. I think that if it were me, I would be pretty apprehensive about going into space after five dogs had died trying to do so. Nevertheless, on April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet cosmonaut, made history as the first person ever to journey into space. Traveling aboard Vostok 1, he completed one orbit around Earth before safely returning to the USSR. While it was a man that made history as the first person in space, it was a dog name Laika that actually paved the way…giving her life in the effort.

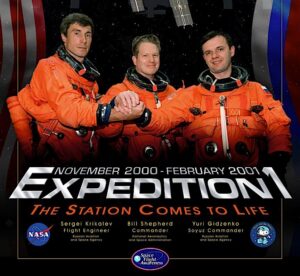

I think most people who followed the building of the International Spece Station were excited about this new venture in the history of space travel. The idea of men and women living and working up there for extended periods of time was amazing…especially when you considered the fact that they would be from multiple countries. Finally, on November 2, 2000, the first residential crew arrived to basically take possession of the International Space Station. The arrival of Expedition 1 heralded a new era of international cooperation in space and the start of the longest continuous human habitation in low Earth orbit. The fact that it is still going on to this day further adds to the enormity of the accomplishment.

I think most people who followed the building of the International Spece Station were excited about this new venture in the history of space travel. The idea of men and women living and working up there for extended periods of time was amazing…especially when you considered the fact that they would be from multiple countries. Finally, on November 2, 2000, the first residential crew arrived to basically take possession of the International Space Station. The arrival of Expedition 1 heralded a new era of international cooperation in space and the start of the longest continuous human habitation in low Earth orbit. The fact that it is still going on to this day further adds to the enormity of the accomplishment.

The space agencies of the United States, Russia, Canada, Japan, and Europe agreed in 1998 to collaborate on the ISS, and its initial components were launched into orbit that year. That in and of itself is amazing. For all these nations to agree to work together to benefit mankind is awesome. Five space shuttle flights and two unmanned Russian flights delivered many core components and partially assembled the station. Yuri Gidzenko

and Sergei Krikalev of Russia, along with NASA’s Bill Shepherd, were the chosen crew for Expedition 1.

and Sergei Krikalev of Russia, along with NASA’s Bill Shepherd, were the chosen crew for Expedition 1.

The trio reached the ISS aboard a Russian Soyuz rocket launched from Kazakhstan. Expedition 1’s tasks primarily involved constructing and installing various components and activating others, a process that proved challenging at times. In one process, for instance, the crew spent over a day activating one of the station’s food warmers. That was probably motivated by hunger!! Of course, I’m sure they had temporary rations available…just in case. During their mission, they received visits and supplies from two unmanned Russian rockets and three space shuttle missions, one of which delivered the photovoltaic arrays, the giant solar panels that provide most of the station’s power. I suppose that was similar to having house guests. Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev were the first to adapt to long-term life in low orbit, orbiting Earth approximately 15.5 times a day and exercising at least two hours daily to counteract muscle atrophy due to low gravity. You wouldn’t think that humans could lose muscle mass in space (or at least, I didn’t), but like with any other muscle strength, it really is a “use it or lose it” situation.

All in all, the three men were in space for a little over three months. It was a momentous event. Then, on March 10, the space shuttle Discovery brought three new residents to replace the Expedition 1 crew. Shepherd, Gidzenko, and Krikalev returned to Earth at the Kennedy Space Center on March 21. Since then, humans have

continuously lived on the ISS, with plans to extend the mission until at least 2030. To date, 236 individuals from 18 countries have visited the station, and several new modules have been added, many aimed at conducting biological research. Like Niel Armstrong said when he stepped on the surface of the moon in 1969, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Yes, it was…and so was this.

continuously lived on the ISS, with plans to extend the mission until at least 2030. To date, 236 individuals from 18 countries have visited the station, and several new modules have been added, many aimed at conducting biological research. Like Niel Armstrong said when he stepped on the surface of the moon in 1969, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” Yes, it was…and so was this.

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

Understandably, the size of the various armies has grown along with human civilization. It is estimated that nearly 28 million armed forces personnel stand at the ready globally in this present day, according to the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of course, peacetime armies would likely be smaller than wartime armies. World War II saw the most soldiers ever to be amassed…with about 70 million soldiers. Approximately 42 million of those soldiers were from the United States, the Soviet Union, Germany, and Japan. These nations armies and related services were four of the largest ever rallied to the battlefield. The largest three were the United States (12,209,000 troops in August 1945), the German Reich (12,070,000 troops in June 1944), and the Soviet Union (11,000,000 troops in June 1943). Those numbers are staggering to think about.

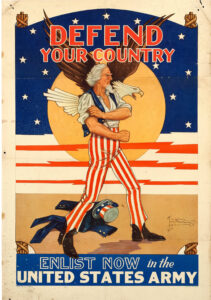

As is expected in a world war, many soldiers are needed. So, the World War II army of the US became the biggest army in history. Citizens of the United States are notorious for patriotism, when we have been attacked. It is like waking a sleeping giant, and we will retaliate with a vengeance. Due in part to that surge of American patriotism and also because of conscription (the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service,

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

mainly a military service), the US Army numbered 12,209,000 soldiers by the end of the war in 1945. It is little surprise that the Japanese found themselves surrendering to the United States on this day, September 2, 1945. of course, the use of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, left little doubt that the Americans not only had the atomic bomb, but we would us it. Basically, their choices were to stay in the fight and die or surrender. They chose the latter, and the rest is history.

In order to determine which of the armies were the largest in history, 24/7 Wall Street reviewed a list of military superpowers from Business Insider. These armies were ranked based on the total number of troops that were serving a country or empire at the point when the army was at its largest. Without doubt, the United States was, and remains to this day, the nation with the largest army in history. Over the years, the armed forces of the United States have been larger and smaller, depending on the need at the time, the administration

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

in charge, and since the draft was discontinued, the number of people who chose to join up to serve their country and to qualify for the GI Bill so that they can get free college. No matter how they got in the service, or how long they stayed, I am very proud of all of our soldiers over the many years of this nation…and I thank them for their service. On this day, the largest army in history accepted the surrender of the Japanese, who had once had the nerve to attack us on our own soil. That was their biggest mistake ever.

As mining work started up in the United States, the need for housing in the area of the mines started up too. This need brought about the “company town” as a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company. Of course, this meant that quite often, all or most of the wages paid to workers, came back to the company in purchases, and as we all know stores and such always have a markup so that they make a profit. Still, they did meet a need, and there was often nowhere else to go. Company towns were often planned with a number of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets, and recreation facilities.

As mining work started up in the United States, the need for housing in the area of the mines started up too. This need brought about the “company town” as a place where all or most of the stores and housing in the town are owned by the same company. Of course, this meant that quite often, all or most of the wages paid to workers, came back to the company in purchases, and as we all know stores and such always have a markup so that they make a profit. Still, they did meet a need, and there was often nowhere else to go. Company towns were often planned with a number of amenities such as stores, houses of worship, schools, markets, and recreation facilities.

The initial motive of building the “company towns” was to improve living conditions for workers. Nevertheless, many have been regarded as controlling and often exploitative. Others were not planned, such as Summit Hill, Pennsylvania, United States, one of the oldest, which began as a Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company mining camp and mine site nine miles from the nearest outside road. Just being that far from anything else around, was prohibitive to those who felt like they were the victims of gouging. Today, many of those “company towns” are ghost towns…lost to a bygone era.

One such town, the town of Kempton, West Virginia was located just a few feet inside the West Virginia border. This strategic location allowed the company to operate using scrip rather than cash. To me that seems like a move to a cashless system that further held the workers there, because the scrip was only accepted at the company businesses, thereby eliminating outside competition. As with any monopoly, this created price  gouging. To make matters worse, if an employee needed a “big ticket” item, such as such as washing machines, radios, and refrigerators, they could get them and make payments. This put many miners in debt, and they were required to pay off the debt before they could move away. The town of Kempton was “founded in 1913 by the Davis Coal and Coke Company, a strip of land 3/4 of a mile long and several hundred feet wide was cleared for the construction of company houses, four to six rooms each with a front yard and a garden in the back. In 1915, J Weimer became the first schoolteacher at $40 a month with 53 pupils. The company store was located on the West Virginia side along with the Opera House that contained the lunchroom, bowling alley, pool table, dancing floor, auditorium, and the post office.” These towns were in reality, “privatized” towns run by a government that was neither elected nor fair, they were simply the ones in control, and if people wanted a job they dealt with the rules.

gouging. To make matters worse, if an employee needed a “big ticket” item, such as such as washing machines, radios, and refrigerators, they could get them and make payments. This put many miners in debt, and they were required to pay off the debt before they could move away. The town of Kempton was “founded in 1913 by the Davis Coal and Coke Company, a strip of land 3/4 of a mile long and several hundred feet wide was cleared for the construction of company houses, four to six rooms each with a front yard and a garden in the back. In 1915, J Weimer became the first schoolteacher at $40 a month with 53 pupils. The company store was located on the West Virginia side along with the Opera House that contained the lunchroom, bowling alley, pool table, dancing floor, auditorium, and the post office.” These towns were in reality, “privatized” towns run by a government that was neither elected nor fair, they were simply the ones in control, and if people wanted a job they dealt with the rules.

Cut out of the Appalachian wilderness, the town of Kempton flourished and became a vibrant community rich in culture and familial spirit. Then, when the mine closed in April of 1950, it just as quickly faded into oblivion. Nevertheless, the former residents tried to keep their connections alive. They held a reunion in 1952 to share their memories and to recall a strong sense of home. Unfortunately, what were once good intention, faded as life got busy and people moved around. Finally, the forest began to reclaim many of the houses as weeds took over and neglect allowed for decay. These days, the fruit trees and annual flowers that were planted long ago

by people who loved the place “still bloom to greet the Spring” and a few of the broken-down buildings still dot the landscape, if one in incline to look around. Newer homes have been built, that are privately owned, and mixed in are a few of the old remnants of times past. With mine reclamation laws in place now, groups have come in and performed archeological digs to recover old work items from the past and restore the site to historical status.

by people who loved the place “still bloom to greet the Spring” and a few of the broken-down buildings still dot the landscape, if one in incline to look around. Newer homes have been built, that are privately owned, and mixed in are a few of the old remnants of times past. With mine reclamation laws in place now, groups have come in and performed archeological digs to recover old work items from the past and restore the site to historical status.

The mission began on July 29, 1953. The B-50 Superfortress piloted by Captain Stanley K O’Kelley had a total of seventeen crewmembers aboard. Its mission was a reconnaissance flight over North Korea. It took off from Honshu, Japan. As the plane headed out across the Sea of Japan, on its way to North Korea, it was intercepted and shot down by a pair of MiG-17s (or possibly MiG-15s) piloted by two Soviet pilots (Yablonskiy and Rybakov), south of Askold Island near Vladivostok. They immediately opened fire, and quickly shot down B-50 Superfortress number 15830. The plane crashed into the Sea of Japan. Amazingly, there was one survivor, and unfortunately, the rest of the crew died in the crash.

The mission began on July 29, 1953. The B-50 Superfortress piloted by Captain Stanley K O’Kelley had a total of seventeen crewmembers aboard. Its mission was a reconnaissance flight over North Korea. It took off from Honshu, Japan. As the plane headed out across the Sea of Japan, on its way to North Korea, it was intercepted and shot down by a pair of MiG-17s (or possibly MiG-15s) piloted by two Soviet pilots (Yablonskiy and Rybakov), south of Askold Island near Vladivostok. They immediately opened fire, and quickly shot down B-50 Superfortress number 15830. The plane crashed into the Sea of Japan. Amazingly, there was one survivor, and unfortunately, the rest of the crew died in the crash.

Captain John Ernst Roche was that survivor, and when it became known that the bomber had failed to return, a search was started. It was thought that some of the other crew might have survived, and life rafts were dropped, but no one else was saved in the end. It was thought that at least four of them (and possibly more) were seen sitting in the raft. Also seen were nine Soviet PT-type boats in the area and at least six of them were heading to the location where debris from the aircraft was later discovered. A Soviet trawler was also spotted in the approximate area. Knowing that, I suppose any of the other survivors were killed. The United States conducted a thorough search of the area by air and sea and was assisted by an Australian ship near the crash site. The search was halted due to dense fog and approaching darkness, and the search was resumed on the morning of July 30, 1953. Captain John Roche, co-pilot of the plane, was wounded but survived the crash by holding onto pieces of the wreckage. He was finally picked up by the Navy ship USS Picking in the early morning hours of July 30, 1953, after floating in the Sea of Japan for about 22 hours. Unfortunately, no other survivors were found. The bodies of Captain Stanley O’Kelley and Master Sergeant Francis Brown were later recovered along the coast of Japan. The remaining 14 members of the crew, which included Robert Stalnaker, were never found. The crew members were First Lieutenant Frank E Beyer (MIA), Master Sergeant Francis L Brown (body recovered), First Lieutenant Edmund J Czyc (MIA), Staff Sergeant Donald W Gabree, (MIA), Airman First Class Roland E Goulet (status unknown), Staff Sergeant Donald G Hill (MIA), First Lieutenant James G Keith (KIA), Captain Stanley K O’Kelley (body recovered), Airman Second Class Earl W Radelin Jr (MIA), Captain John E Roche (rescued the next day on July 30, 1953), Airman Second Class, Charles J Russell (MIA), First Lieutenant Warren J Sanderson (MIA), First Lieutenant Robert E Stalnaker (MIA), Major Francisco J Tejeda (MIA), Captain John C Ward (MIA), First Lieutenant Lloyd C Wiggins (MIA), and Airman Second Class James E Woods (MIA).

The B50 Superfortress number 47-145 (Manufacture Number 15830) was built by Boeing. It was delivered to the US Air Force (USAF) as B-50B-50-BO Superfortress serial number 47-145. So that the bomber could be

used as a spy plane, it was modified as RB-50G ELINT with additional radar and B-50D type nose, sometimes also referred to as RB-50D. It was then assigned as a spy plane, to the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (91st SRS) based at Yokato AFB. It was working in that capacity when it was shot down.

used as a spy plane, it was modified as RB-50G ELINT with additional radar and B-50D type nose, sometimes also referred to as RB-50D. It was then assigned as a spy plane, to the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron (91st SRS) based at Yokato AFB. It was working in that capacity when it was shot down.