tuberculosis

Lady Jane Grey was the great-granddaughter of King Henry VII and the cousin of King Edward VI. Lady Jane and Edward, who were the same age, and they were almost married in 1549. Nevertheless, in May of 1553, Lady Jane Grey was married to Lord Guildford Dudley, the son of John Dudley, the duke of Northumberland. Soon after her marriage, King Edward fell ill with tuberculosis, which would take his life in the end. This would set off a cacophony of arguments that would not end well.

Lady Jane Grey was the great-granddaughter of King Henry VII and the cousin of King Edward VI. Lady Jane and Edward, who were the same age, and they were almost married in 1549. Nevertheless, in May of 1553, Lady Jane Grey was married to Lord Guildford Dudley, the son of John Dudley, the duke of Northumberland. Soon after her marriage, King Edward fell ill with tuberculosis, which would take his life in the end. This would set off a cacophony of arguments that would not end well.

Even in those days, discord over religion brought fights, even to the point of violence. The Catholics and Protestant religions were at war. Mostly it wasn’t a physical war, but certainly sometimes it was an all-out war. Lady Jane as it turned out, was a Protestant, while King Edward VI’s half-sister, Mary was a Catholic. King Edward VI did not want to hand over his throne to Mary. Lady Jane’s father-in-law, John Dudley agreed, and so persuaded the dying king that Lady Jane, a Protestant, should be chosen the royal successor over Edward’s half-sister Mary, a Catholic. So, in June 1553, the dying Edward VI wrote his will, in which he nominated Jane and her male heirs as successors to the Crown. King Edward VI agreed that Mary should not succeed him because she was Catholic would not support the reformed Church of England, whose foundation Edward laid. The will removed his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, from the line of succession on account of their illegitimacy, subverting their lawful claims under the Third Succession Act. Through Northumberland, Edward’s letters patent in favor of Lady Jane was signed by the entire privy council, bishops, and other notables.

On July 6, 1553, Edward died, and four days later Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed queen of England. The 15-year-old Lady Jane, beautiful and intelligent, had only reluctantly agreed to be put on the throne, and it would be the worst decision of her life. While Lady Jane’s ascendance was supported by the Royal Council, the populace supported Mary, as the rightful heir. Two days into Queen Jane’s reign, Dudley departed London with an army in an effort to suppress Mary’s forces. I don’t know if that was a good idea, or not…likely not, because in his absence the Council declared him a traitor and Mary the queen. Queen Jane’s reign was just nine days.

The next day, July 20th, most of Dudley’s army deserted him, and he was immediately arrested. The same day, now Lady Jane was imprisoned in the Tower of London. Her father-in-law was condemned for high treason, and on August 23rd he was executed. On November 13th, Lady Jane and her husband, Guildford Dudley, were also found guilty of treason. They were both sentenced to death, but because of their youth and relative innocence Queen Mary had chosen not to carry out the death sentences.

Lady Jane’s father, Henry Grey grew furious in early 1554, and joined Sir Thomas Wyatt in an insurrection against Queen Mary, because she had announced her intention to marry Philip II of Spain. While suppressing

the revolt, Queen Mary decided it was going to be necessary to eliminate all her political opponents, whether she wanted to or not, and on February 7th she signed the death warrants of Lady Jane and her husband. On the morning of February 12th, Lady Jane watched her husband being carried away to execution from the window of her cell in the Tower of London. That must have been horrible in so many ways. This was her husband being led to his death, but she also knew that she was next. Then, just two hours later she was also executed. “As British tradition tells the story, after the 16-year-old girl was beheaded, her executioner held Lady Jane’s head aloft and recited the words: ‘So perish all the queen’s enemies! Behold, the head of a traitor!'”

the revolt, Queen Mary decided it was going to be necessary to eliminate all her political opponents, whether she wanted to or not, and on February 7th she signed the death warrants of Lady Jane and her husband. On the morning of February 12th, Lady Jane watched her husband being carried away to execution from the window of her cell in the Tower of London. That must have been horrible in so many ways. This was her husband being led to his death, but she also knew that she was next. Then, just two hours later she was also executed. “As British tradition tells the story, after the 16-year-old girl was beheaded, her executioner held Lady Jane’s head aloft and recited the words: ‘So perish all the queen’s enemies! Behold, the head of a traitor!'”

In 1913, Milunka Savic joined the Serbian army in her brother’s place, cutting her hair and donning men’s clothes. You might wonder why she would do such a thing, and why her brother didn’t go and do his duty. This story isn’t about her heroics in the face of her brother’s cowardice, but rather her heroics when her brother truly could not serve. In 1912, Milunka’s brother received call-up papers for mobilization for the First Balkan War, but at the time, he was quite ill with tuberculosis. Milunka could have just told the authorities that he was ill, and he would have been excused, but she knew that the war effort was important, so she chose to go in his place. She started her transformation by cutting her hair and started wearing men’s clothes, then she joined the Serbian army. She saw combat almost immediately, and while many women of that era would have turned tail and run, she did not. She received her first medal and was promoted to corporal in the Battle of Bregalnica. While she was engaged in battle, Milunka was wounded, and as she was being treated in the hospital, her true gender was discovered by some very surprised physicians. I suppose you could say that she hadn’t thought this part of the plan out very well, or maybe she just didn’t plan to be wounded!! Nevertheless, here she was, and she had a problem.

In 1913, Milunka Savic joined the Serbian army in her brother’s place, cutting her hair and donning men’s clothes. You might wonder why she would do such a thing, and why her brother didn’t go and do his duty. This story isn’t about her heroics in the face of her brother’s cowardice, but rather her heroics when her brother truly could not serve. In 1912, Milunka’s brother received call-up papers for mobilization for the First Balkan War, but at the time, he was quite ill with tuberculosis. Milunka could have just told the authorities that he was ill, and he would have been excused, but she knew that the war effort was important, so she chose to go in his place. She started her transformation by cutting her hair and started wearing men’s clothes, then she joined the Serbian army. She saw combat almost immediately, and while many women of that era would have turned tail and run, she did not. She received her first medal and was promoted to corporal in the Battle of Bregalnica. While she was engaged in battle, Milunka was wounded, and as she was being treated in the hospital, her true gender was discovered by some very surprised physicians. I suppose you could say that she hadn’t thought this part of the plan out very well, or maybe she just didn’t plan to be wounded!! Nevertheless, here she was, and she had a problem.

She could have been in a lot of trouble at this point, but she had proven to such a competent soldier, her commanding officers were hesitant to punish her. It was decided that they would send her to a nursing division, but Milunka informed them that she would serve her country only in combat. This had to be an amazing woman, who was far ahead of her time in the area of women in combat. While they could have insisted, I suppose they would have also lost not only a nurse, but a great soldier, so they relented, and she went back to her unit. Milunka went on to fight in three wars and earn seven medals, including the Croix de Guerre and the British medal of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael. It is believed that she may in fact be the most-decorated female combatant not only in Serbia, but in the entire history of warfare. To me, Milunka Savic was not just a hero for her fighting efforts, but for stepping up when her brother could not. I’m sure he is quite proud of his sister.

She was demobilized in 1919, and turned down an offer to move to France, where she was eligible to collect a comfortable French army pension. Milunka found work as a postal worker in Belgrade. In 1923, she married Veljko Gligorijevic, whom she met in Mostar, and divorced immediately after the birth of their daughter Milena. She loved children and went on to adopt three other daughters. In the interwar period, Milunka was largely forgotten by the general public. Life was not easy for her. She worked several menial jobs up to 1927, after which she had steady employment as a cleaning lady in the State Mortgage Bank. Eight years later, she was promoted to cleaning the offices of the general manager…such menial labor for a hero.

During the German occupation of Serbia in World War II, Milunka refused to attend a banquet organized by Milan Nedic, which was to be attended by German generals and officers. She was arrested and taken to Banjica concentration camp, where she was imprisoned for ten months. By the late 1950s, her daughter became ill, and before long she found herself living in poverty. In 1972, public pressure and a newspaper article highlighting her difficult housing and financial situation led to her finally receiving the recognition she deserved. She was given a small apartment by the Belgrade City Assembly. She died in Belgrade on October 5, 1973, at the age of 85, and was buried in Belgrade New Cemetery.

Marie Sklodowska was born in an era when women seldom got a very long education, if they got one at all. Born on November 7, 1867 in Warsaw (modern-day Poland). Sklodowska was the youngest of five children, following siblings Zosia, Józef, Bronya and Hela. Their parents were both teachers. Her father, Wladyslaw, was a math and physics instructor. When she was only 10, Sklodowska lost her mother, Bronislawa, to tuberculosis. Sklodowska, being a woman, probably should have grown up to be a wide and mother, dependent on her husband for everything…not that that is a horrible thing, because it isn’t, but it was not all she wanted. She had a good mind for Physics and Chemistry…both subjects were almost unheard of for women in those days.

Marie Sklodowska was born in an era when women seldom got a very long education, if they got one at all. Born on November 7, 1867 in Warsaw (modern-day Poland). Sklodowska was the youngest of five children, following siblings Zosia, Józef, Bronya and Hela. Their parents were both teachers. Her father, Wladyslaw, was a math and physics instructor. When she was only 10, Sklodowska lost her mother, Bronislawa, to tuberculosis. Sklodowska, being a woman, probably should have grown up to be a wide and mother, dependent on her husband for everything…not that that is a horrible thing, because it isn’t, but it was not all she wanted. She had a good mind for Physics and Chemistry…both subjects were almost unheard of for women in those days.

As a child, Sklodowska took after her father. She was bright and curious, and she excelled at school. Still, despite being a top student in her secondary school, she could not attend the men’s-only University of Warsaw. She instead continued her education in Warsaw’s “floating university,” a set of underground, informal classes held in secret. Both Marie and her sister, Bronya dreamed of going abroad to earn an official degree, but they lacked the financial resources to pay for more schooling. Sklodowska would not give up her dream. She worked out a deal with her sister, “She would work to support Bronya while she was in school, and Bronya would return the favor after she completed her studies.”

Sklodowska worked as a tutor and a governess for the next five years. She didn’t want to get behind, so she used her spare time to study…reading about physics, chemistry and math. Then in 1891, Sklodowska finally made her way to Paris and enrolled at the Sorbonne. She threw herself into her studies, but this dedication had a personal cost: with little money, Sklodowska survived on buttered bread and tea. Sometimes, her health suffered because of her poor diet. Nevertheless, Sklodowska completed her master’s degree in physics in 1893 and earned another degree in mathematics the following year.

You might be wondering exactly who Marie Sklodowska was, and why she was important. It might help to know that on July 26, 1895, Marie got married to French physicist, Pierre Curie. They were introduced by a colleague of Marie’s after she graduated from Sorbonne University. Marie had received a commission to perform a study on different types of steel and their magnetic properties and needed a lab for her work. As most people already know, she did her work at a great cost to her own health, but what most people probably don’t know, is that the radiation levels Curie was exposed to were so powerful that her notebooks must now be kept in lead-lined boxes, and it’s not just Curie’s manuscripts that are too dangerous to touch, either. If you visit the Pierre and Marie Curie collection at the Bibliotheque Nationale in France, many of her personal possessions…from her furniture to her cookbooks…require protective clothing to be safely handled. You’ll also have to sign a liability waiver, just in case.

In those days, things like radiation and it’s dangers were not known. Marie Curie was basically walking around with bottles of polonium and radium, both highly radioactive compounds, in her pockets all the time. She even kept capsules full of the dangerous chemicals on her shelf. “One of our joys was to go into our workroom at night; we then perceived on all sides the feebly luminous silhouettes of the bottles of capsules containing our products,” Marie, the Nobel Prize-winning scientist wrote in her autobiography. “It was really a lovely sight and one always new to us. The glowing tubes looked like faint, fairy lights.” In case you didn’t know, Marie Curie discovered radioactivity. Also, along with her husband, Pierre, they discovered the radioactive elements, Polonium and Radium, while working with the mineral, Pitchblende…a form of the mineral Uraninite occurring in  brown or black masses and containing radium. She also championed the development of X-rays, following her husband’s death in a street accident in Paris on 19 April 1906.

brown or black masses and containing radium. She also championed the development of X-rays, following her husband’s death in a street accident in Paris on 19 April 1906.

The fact that the notebook and related paraphernalia are still radioactive a century later is not as well known. The most common isotope of radium, the deadly chemical Curie carried in her pockets, has a half-life of 1,601 years. That said, people will not be able to go digging through the Curie’s library any time in this century, either. It is also known now, but wasn’t then, that the chemicals would end Curie’s life at a fairly early age. Curie died on July 4, 1934, of aplastic anemia, believed to be caused by prolonged exposure to radiation. She was 58 years old.

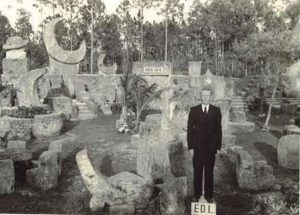

Edward Leedskalnin was a bit of an eccentric, which might have been caused by the sadness of lost love. When Edward was suddenly rejected by his 16 year old fiancée Agnes Skuvst in Latvia, just one day before the wedding, he decided to immigrate to America. Once there, he came down with allegedly terminal tuberculosis, but was spontaneously healed. He believed that magnets had some effect on his disease. I don’t know about that part, but he lived much longer that he was ever expected to.

Edward Leedskalnin was a bit of an eccentric, which might have been caused by the sadness of lost love. When Edward was suddenly rejected by his 16 year old fiancée Agnes Skuvst in Latvia, just one day before the wedding, he decided to immigrate to America. Once there, he came down with allegedly terminal tuberculosis, but was spontaneously healed. He believed that magnets had some effect on his disease. I don’t know about that part, but he lived much longer that he was ever expected to.

Leedskalnin decided to build himself a home where he could live out his years in solitude. The resulting “home” was eventually names Coral Castle, but was originally named “Ed’s Place.” Leedskalnin originally built the castle in Florida City, Florida, around 1923. Florida City, which borders the Everglades, is the southernmost city in the United States that is not on an island. It was an extremely remote location with very little development at the time. Leedskalnin built the castle by himself, out of Oolite Limestone. Edward spent more than 28 years building Coral Castle, refusing to allow anyone to view him while he worked. A few teenagers claimed to have watched his work a few times and reported that he had caused the blocks of coral to move like hydrogen balloons. The only tool that Leedskalnin spoke of using was a “perpetual motion holder”. The stones are fastened together without mortar. They are set on top of each other using their weight to keep them together. The craftsmanship detail is so skillful and the stones are connected with such precision that no light passes through the joints. The 8-foot tall vertical stones that make up the perimeter wall have a uniform height. Even with the passage of decades the stones have not shifted.

Leedskalnin purchased the land from Ruben Moser whose wife had assisted him when he had a very bad bout with tuberculosis. The castle remained in Florida City until about 1936 when Leedskalnin decided to move and take the castle with him. He renamed it “Rock Gate.” The move was an even more amazing feat the the first building of the castle. Its second and final location has the mailing address of 28655 South Dixie Highway, Miami, FL 33033, which now appears within Leisure City but which is actually unincorporated county territory. He reportedly chose relocation as a means to protect his privacy when discussion about developing land in the original area of the castle started. He spent three years moving the component structures of Coral Castle 10 miles north of Florida City to its current location outside Homestead, Florida.

At Florida City, Leedskalnin allowed visitors to the castle, charging them ten cents apiece to tour the castle grounds, but after moving to Homestead, he asked for donations of twenty five cents. Nevertheless, he let visitors enter free if they had no money. There are signs carved into rocks at the front gate to “Ring Bell Twice.” He would come down from his living quarters in the second story of the castle tower close to the gate and conduct the tour. Leedskalnin never told anyone who asked him how he made the castle. He would simply answer “It’s not difficult if you know how.” When Leedskalnin became ill in November 1951, he put a sign on the door of the front gate “Going to the Hospital” and took the bus to Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami. Leedskalnin suffered a stroke at one point, either before he left for the hospital or at the hospital. He died twenty-eight days later of Pyelonephritis (a kidney infection) at the age of 64. His death certificate noted that his death was a result of “uremia; failure of kidneys, as a result of the infection and abscess.” While the property was being investigated, $3,500 was found among Leedskalnin’s personal belongings. Leedskalnin had made his income from conducting tours, selling pamphlets about various subjects (including magnetic currents) and the sale of a portion of his 10-acre property for the construction of U.S. Route 1. As Leedskalnin had no will, the castle became the property of his closest living relative in America, a nephew from Michigan named Harry. Coral Castle’s website reports that the nephew was in poor health and he sold the castle to an Illinois family in 1953. However, this story differs from the obituary of a former Coral Castle owner, Julius

Levin, a retired jeweler from Chicago, Illinois. The obituary states Levin had purchased the land from the state of Florida in 1952 and may not have been aware there was even a castle on the land. The new owners turned it into a tourist attraction and changed the name of Rock Gate to Rock Gate Park, and later to Coral Castle. In January 1981, Levin sold the castle to Coral Castle, Inc., for $175,000. The company retains ownership today.

Levin, a retired jeweler from Chicago, Illinois. The obituary states Levin had purchased the land from the state of Florida in 1952 and may not have been aware there was even a castle on the land. The new owners turned it into a tourist attraction and changed the name of Rock Gate to Rock Gate Park, and later to Coral Castle. In January 1981, Levin sold the castle to Coral Castle, Inc., for $175,000. The company retains ownership today.

Tuberculosis was a disease that brought terror to the hearts of people over the years…especially right after World War II, but even before World War II, being diagnosed with Tuberculosis was like being given a death sentence. People had to be quarantined, so they wouldn’t infect those around them, since the disease is airborne. All too often it was too late by the time they knew they needed to be quarantined. Any serious disease can be scary for the people in areas affected, but this one was taken to a completely different level. In an effort to prevent Tuberculosis from being passed from child to child, the schools began a new movement, known as the Open-Air School. The movement required the establishment of schools that combined medical surveillance with A method of learning that was adapted to students with pre-tuberculosis…an obsolete term for the pre-clinical stage of tuberculosis. The new institution was established by doctors researching new prophylactic methods, and educators interested in an open air educational experience.

Tuberculosis was a disease that brought terror to the hearts of people over the years…especially right after World War II, but even before World War II, being diagnosed with Tuberculosis was like being given a death sentence. People had to be quarantined, so they wouldn’t infect those around them, since the disease is airborne. All too often it was too late by the time they knew they needed to be quarantined. Any serious disease can be scary for the people in areas affected, but this one was taken to a completely different level. In an effort to prevent Tuberculosis from being passed from child to child, the schools began a new movement, known as the Open-Air School. The movement required the establishment of schools that combined medical surveillance with A method of learning that was adapted to students with pre-tuberculosis…an obsolete term for the pre-clinical stage of tuberculosis. The new institution was established by doctors researching new prophylactic methods, and educators interested in an open air educational experience.

In 1904, Dr Bernhard Bendix and pedagogue Hermann Neufert founded the first school of this kind: the Waldeschule of Charlottenburg, near Berlin, Germany. Classes were conducted in the woods to offer open-air therapy to young city dwellers with pre-tuberculosis. The experiment, conducted by the International Congresses of Hygiene, was immediately attempted throughout Europe and North America: in Belgium in 1904, in Switzerland, England, Italy, and France in 1907, in the United States in 1908, in Hungary in 1910, and in Sweden in 1914. The schools were called “schools of the woods” or “open air schools.” Often they were remote from cities, set up in tents, prefabricated barracks, or re-purposed structures, and were run during the summer. Some of the more noteworthy experiments were the School in the Sun, in Cergnat, Switzerland and the school of Uffculme near Birmingham, England.  The School of the Sun used helio-therapy in 1910. Dr Auguste Rollier sent the children up to the mountains every morning equipped with portable equipment. The school of Uffculme, noted for its architecture, allowed each class to occupy its own independent pavilion in 1911.

The School of the Sun used helio-therapy in 1910. Dr Auguste Rollier sent the children up to the mountains every morning equipped with portable equipment. The school of Uffculme, noted for its architecture, allowed each class to occupy its own independent pavilion in 1911.

After World War I the movement became organized. The first International Congress took place in Paris in 1922, at the initiative of The League for Open Air Education created in France in 1906, and of its president, Gaston Lemonier. There were four more congresses: in Belgium in 1931; in Germany in 1936, marked by the involvement of German doctor Karl Triebold; in Italy in 1949; and in Switzerland in 1956. National committees were created. Jean Duperthuis, a close associate of Adolphe Ferrière (1879–1960), the well-known pedagogue and theorist of New Education, created the International Bureau of Open Air Schools to collect information on how these schools worked. Testimonies described an educational experience inspired by New Education, with much physical exercise, regular medical checkups, and a closely monitored diet, but there has been little formal study of the majority of these schools.

According to the ideas of the open air school, the architecture had to provide wide access to the outdoors, with large bay windows and a heating system that would permit working with the windows open. The most remarkable of these schools were in Amsterdam, Holland by architect Jan Duiker (1929–1930), in Suresnes, France by Eugène Beaudoin and Marcel Lods (1931–1935), and Copenhagen, Denmark by Kai Gottlob (1935–1938). From what I have seen, most of these school were held completely outdoors. I don’t know if the impact on Tuberculosis was as profound as they had hoped, but there were good things that came out of the  experiments. The movement had an influence on the evolution of education, hygiene, and architecture. School buildings, for example, adopted the concept of classes open to the outdoors, as in Bale, Switzerland (1938–1939, architect Hermann Baur), Impington, England (1939, Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry), and in Los Angeles (1935, Richard Neutra). This influence is the major contribution of the open air schools movement, although the introduction of antibiotics, which increasingly provided a cure for Tuberculosis, pretty much made them obsolete after World War II. Nevertheless, fresh air, exercise, and playtime for young children have all remained an important part of the school day, and thankfully, Tuberculosis is on the decline, although it still ranks in the top 10 of fatal diseases.

experiments. The movement had an influence on the evolution of education, hygiene, and architecture. School buildings, for example, adopted the concept of classes open to the outdoors, as in Bale, Switzerland (1938–1939, architect Hermann Baur), Impington, England (1939, Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry), and in Los Angeles (1935, Richard Neutra). This influence is the major contribution of the open air schools movement, although the introduction of antibiotics, which increasingly provided a cure for Tuberculosis, pretty much made them obsolete after World War II. Nevertheless, fresh air, exercise, and playtime for young children have all remained an important part of the school day, and thankfully, Tuberculosis is on the decline, although it still ranks in the top 10 of fatal diseases.

In the old west, few women went on to get a higher education, and even fewer became doctors. It was thought of as a man’s occupation, and the few women who dared to go into that field, were often looked at with distrust, and even disdain. People thought that women belonged in the home raising a family. Some didn’t even attempt to hide the dislike of women in medicine. Susan Anderson, MD was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1870. Her family moved to the mining camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado during her childhood. In 1893, Anderson left Cripple Creek to attend medical school at the University of Michigan. She graduated in 1897. During her time in medical school, Anderson contracted tuberculosis and soon returned to her family in Cripple Creek, where she set up her first practice.

In the old west, few women went on to get a higher education, and even fewer became doctors. It was thought of as a man’s occupation, and the few women who dared to go into that field, were often looked at with distrust, and even disdain. People thought that women belonged in the home raising a family. Some didn’t even attempt to hide the dislike of women in medicine. Susan Anderson, MD was born in Fort Wayne, Indiana in 1870. Her family moved to the mining camp of Cripple Creek, Colorado during her childhood. In 1893, Anderson left Cripple Creek to attend medical school at the University of Michigan. She graduated in 1897. During her time in medical school, Anderson contracted tuberculosis and soon returned to her family in Cripple Creek, where she set up her first practice.

Anderson spent the next three years sympathetically tending to patients, but her father insisted that Cripple Creek, a lawless mining town at the time. He felt like it was no place for a woman, so Anderson moved to Denver. In Denver, she had a tough time securing patients. The people in Denver were reluctant to see a woman doctor. She then moved to Greeley, Colorado, where she worked as a nurse for six years. Somehow, people accepted a woman as a nurse, probably because they looked at it as just following the orders of the doctor, who was ultimately in charge.

Her tuberculosis got worse during this time, so she felt she needed a more cold and dry climate. She made the  decision to move to Fraser, Colorado in 1907. Fraser’s elevation of over 8,500 feet, definitely made the area cold and dry. Anderson was most concerned with getting her disease under control and didn’t open a practice. She didn’t even tell people that she was a doctor. Nevertheless, the word soon got out and the locals began to ask for her advice on various ailments, which soon led to her practicing her skills once again. Her reputation spread as she treated families, ranchers, loggers, railroad workers, and even an occasional horse or cow, which was not uncommon at the time. The vast majority of her patients required her to make house calls, though she never owned a horse or a car. Instead, she dressed in layers, wore high hip boots, and trekked through deep snows and freezing temperatures to reach her patients. Now that is dedication…especially for a woman trying to recover from Tuberculosis.

decision to move to Fraser, Colorado in 1907. Fraser’s elevation of over 8,500 feet, definitely made the area cold and dry. Anderson was most concerned with getting her disease under control and didn’t open a practice. She didn’t even tell people that she was a doctor. Nevertheless, the word soon got out and the locals began to ask for her advice on various ailments, which soon led to her practicing her skills once again. Her reputation spread as she treated families, ranchers, loggers, railroad workers, and even an occasional horse or cow, which was not uncommon at the time. The vast majority of her patients required her to make house calls, though she never owned a horse or a car. Instead, she dressed in layers, wore high hip boots, and trekked through deep snows and freezing temperatures to reach her patients. Now that is dedication…especially for a woman trying to recover from Tuberculosis.

During the many years that “Doc Susie,” which she familiarly became known as, practiced in the high mountains of Grand County, one of her busiest times was during the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919. Like people all over the world, Fraser locals also became sick in great numbers, and Dr Anderson found herself rushing from one deathbed to the next.

Another busy time for her was when the six-mile Moffat Tunnel was being built through the Rocky Mountains. Not long after construction began, she found herself treating numerous men who were injured during  construction. During this time, she was also asked to become the Grand County Coroner, a position that enabled her to confront the Tunnel Commission regarding working conditions and accidents. She hoped to make a difference. In the five years it took to complete the tunnel, there were about 19 who died and hundreds injured.

construction. During this time, she was also asked to become the Grand County Coroner, a position that enabled her to confront the Tunnel Commission regarding working conditions and accidents. She hoped to make a difference. In the five years it took to complete the tunnel, there were about 19 who died and hundreds injured.

Unlike physicians of today, Dr Anderson never became “rich” practicing her skills. Im not even sure you would say she made a middle class living, because she was often paid in firewood, food, services, and other items that could be bartered. Doc Susie continued to practice in Fraser until 1956. She died in Denver on April 16, 1960 and was buried in Cripple Creek, Colorado.

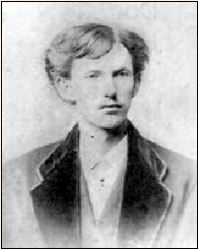

When we think of gunslingers from the old west, a number of names come to mind…among them, Doc Holliday. John Henry “Doc” Holliday was born August 14, 1851 in Griffin, Georgia, to Henry Burroughs Holliday and Alice Jane (McKey) Holliday. When John was just 15 years old, his mother died of Tuberculosis on September 16, 1866. His adopted brother also died of Tuberculosis. In 1870, at the age of 19, Holliday left home for Philadelphia, and on March 1, 1872, he received his Doctor of Dental Surgery degree from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery. Holliday graduated five months before his 21st birthday, so the school held his degree until he turned 21, which was the minimum age required to practice dentistry.

When we think of gunslingers from the old west, a number of names come to mind…among them, Doc Holliday. John Henry “Doc” Holliday was born August 14, 1851 in Griffin, Georgia, to Henry Burroughs Holliday and Alice Jane (McKey) Holliday. When John was just 15 years old, his mother died of Tuberculosis on September 16, 1866. His adopted brother also died of Tuberculosis. In 1870, at the age of 19, Holliday left home for Philadelphia, and on March 1, 1872, he received his Doctor of Dental Surgery degree from the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery. Holliday graduated five months before his 21st birthday, so the school held his degree until he turned 21, which was the minimum age required to practice dentistry.

Many people remember Doc Holliday from the gunfight at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, but prior to that time, he was in Saint Louis, Missouri and Atlanta, Georgia. He started has practice in Saint Louis, but switched to Atlanta less than four months later  to join a dental practice there. While in Atlanta, Holliday and some friends got into an altercation, and in the end, Holliday went and got a shotgun. He came back and started shooting, either at or over the heads of the other men. Whether or not anyone was killed is up for debate, but Holliday gained a reputation as a gunslinger.

to join a dental practice there. While in Atlanta, Holliday and some friends got into an altercation, and in the end, Holliday went and got a shotgun. He came back and started shooting, either at or over the heads of the other men. Whether or not anyone was killed is up for debate, but Holliday gained a reputation as a gunslinger.

Soon after moving to Atlanta, Holliday developed a bad cough. The doctors told him that he had Tuberculosis. I can’t even begin to imagine how Holliday felt about that diagnosis. He had watched his mother die of that very disease, as well as his adopted brother. Holliday was told he needed to move to a dryer  climate, if he wanted to extend his life. He moved to Dallas, Texas. His dental practice could have suffered because of his ill health, or it could have been caused by the fact that he would rather play poker than work on teeth. Holliday was a decent poker player, so he found that it was a pretty good way to make a living. In 1875, Holliday was arrested in Dallas for participating in a shootout.

climate, if he wanted to extend his life. He moved to Dallas, Texas. His dental practice could have suffered because of his ill health, or it could have been caused by the fact that he would rather play poker than work on teeth. Holliday was a decent poker player, so he found that it was a pretty good way to make a living. In 1875, Holliday was arrested in Dallas for participating in a shootout.

Holliday left Dallas and began drifting between booming Wild West towns like Denver, Cheyenne, Deadwood, and Dodge City. He made his living at card tables, with heavy drinking and late night. All of these things were quite aggravating to his Tuberculosis. By 1887, Holliday’s hard life had caught up with him, forcing him to seek treatment in a sanitarium in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. Finally, on this day, November 8, 1887, Doc Holliday, gunslinger, gambler, and occasional dentist, lost his battle with Tuberculosis, just like his mother and adoptive brother before him.