trading post

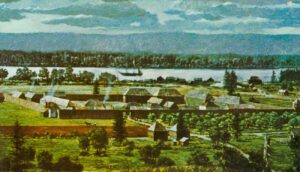

Fort Vancouver was founded in 1824. The fort functioned as a trading post and the main office for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia District. The Columbia District was vast and spanned an area of 700,000 square miles, extending from Russian Alaska to Mexican California, and from the Rocky Mountains to the Hawaiian Islands. The fort itself was located on the northern shore of the Columbia River in what is now Vancouver, Washington, and it was named in honor of Captain George Vancouver. George Simpson of Hudson Bay played a key role in the establishment of the fort, and Dr John McLoughlin was chosen as its inaugural manager. So good at his job, McLoughlin, became known as the Father of Oregon, because he extended a warm welcome and offered assistance to newcomers in the region. While this endeared him for the people, it was not something that the Hudson’s Bay Company was happy about these actions, mostly because new settlers interfered with the lucrative fur trade. In the end, McLoughlin left the organization and founded Oregon City in the Willamette Valley.

Fort Vancouver was founded in 1824. The fort functioned as a trading post and the main office for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Columbia District. The Columbia District was vast and spanned an area of 700,000 square miles, extending from Russian Alaska to Mexican California, and from the Rocky Mountains to the Hawaiian Islands. The fort itself was located on the northern shore of the Columbia River in what is now Vancouver, Washington, and it was named in honor of Captain George Vancouver. George Simpson of Hudson Bay played a key role in the establishment of the fort, and Dr John McLoughlin was chosen as its inaugural manager. So good at his job, McLoughlin, became known as the Father of Oregon, because he extended a warm welcome and offered assistance to newcomers in the region. While this endeared him for the people, it was not something that the Hudson’s Bay Company was happy about these actions, mostly because new settlers interfered with the lucrative fur trade. In the end, McLoughlin left the organization and founded Oregon City in the Willamette Valley.

The fort’s original compound consisted of approximately 40 structures, including residences, a school, library, pharmacy, chapel, blacksmith shop, and a sizable manufacturing plant, all encircled by a 20-foot-tall palisade stretching roughly 750 feet in length and 450 feet in width. Beyond its imposing walls, the extensive corporate entity also constructed supplementary dwellings, a shipyard, hospital, distillery, tannery, sawmill, dairy, farmlands, and orchards. Serving as the district’s administrative hub and main supply depot, the fort functioned as the center of a wide-reaching fur trading network. This network comprised two dozen posts, six vessels, and approximately 600 employees at the height of the trading season, with the majority engaged in agriculture.

Fort Vancouver emerged as a hub of activity and influence, bolstered by a multicultural village home to individuals from more than 35 ethnic and tribal groups. Despite being a British outpost, the predominant languages spoken were Canadian French and Chinook Jargon. It grew to be one of the largest settlements in  the West at that time and acted as the initial terminus of the Oregon Trail for American settlers. In the late 1840s and early 1850s, diminishing profits from trapping and the influx of settlers prompted a transition from fur trading to land-based commerce. This shift altered the village’s dynamics and demographics. The Hawaiian workforce expanded, and by the 1850s, the village was commonly referred to as “Kanaka Town” or “Kanaka Village,” derived from the Hawaiian term for “person.” The village served not only as living quarters for the Company’s employees but also as the location for establishing a permanent US Army presence in the Pacific Northwest. In May 1849, the US Army established Camp Columbia, situated on an elevation 20 feet above the trading post.

the West at that time and acted as the initial terminus of the Oregon Trail for American settlers. In the late 1840s and early 1850s, diminishing profits from trapping and the influx of settlers prompted a transition from fur trading to land-based commerce. This shift altered the village’s dynamics and demographics. The Hawaiian workforce expanded, and by the 1850s, the village was commonly referred to as “Kanaka Town” or “Kanaka Village,” derived from the Hawaiian term for “person.” The village served not only as living quarters for the Company’s employees but also as the location for establishing a permanent US Army presence in the Pacific Northwest. In May 1849, the US Army established Camp Columbia, situated on an elevation 20 feet above the trading post.

Although the Hudson’s Bay Company aided the soldiers by providing access to their sawmill for timber cutting, the construction of the post was delayed due to the California Gold Rush. The rush led to a shortage of labor and supplies, inflated prices, and a high number of desertions. Despite these challenges, the remaining workers persevered, and the construction was finally completed in the spring of 1851. Subsequently, the military post was renamed Columbia Barracks. Initially, traders and soldiers coexisted peacefully, with the Army leasing numerous village buildings and employing additional local residents. During the early 1850s, the Army erected a number of structures, notably the Quartermaster Depot and the residence of Captain Rufus Ingalls, which Ulysses S Grant called home from 1852 to 1853. The military post grew to encompass more than 10,000 acres and was rechristened as Fort Vancouver Military Reservation.

Amidst escalating pressures from new settlers seeking land and diminishing profits from trapping, the relationship between traders and soldiers worsened during the latter part of the 1850s. Ultimately, in June 1860, the Hudson’s Bay Company relocated its operations to Victoria, British Columbia. Soldiers took over some ancient trading post structures, and the Vancouver Arsenal was founded in 1859. Yet, in 1866, a devastating fire obliterated all traces of the original trading post edifices. Nevertheless, the soldiers remained and reconstructed the structures, which included two two-story barracks situated on opposite ends of the parade ground, each featuring a kitchen and a mess hall at the back. Seven log buildings and four framed structures functioned as the Officers’ Quarters. In 1879, the outpost was designated as Vancouver Barracks and underwent expansion during World War I. Subsequently, in World War II, it served as a staging ground for the Seattle Port of Embarkation. The fort was ultimately decommissioned in 1946.

Due to its historical importance, the location was designated a US National Monument on June 19, 1948, and

was later reclassified as the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site on June 30, 1961. Presently, the site features a full-scale reconstruction of the original fort, complete with the manager’s house, bakery, blacksmith shop, central stores, and fur storage area. A variety of exhibits are open for public viewing, and the site hosts re-enactments and demonstrations year-round.

was later reclassified as the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site on June 30, 1961. Presently, the site features a full-scale reconstruction of the original fort, complete with the manager’s house, bakery, blacksmith shop, central stores, and fur storage area. A variety of exhibits are open for public viewing, and the site hosts re-enactments and demonstrations year-round.

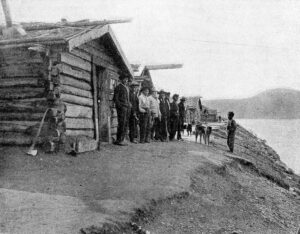

Fort Selkirk was built as a trading post on the Yukon River at the junction of the Pelly River in Canada’s Yukon. For many years it was home to the Selkirk First Nation, also known a Northern Tutchone. The Selkirk First Nation is a First Nation self-government in the Canadian territory, Yukon. “First Nation self-government is a formal structure through which Indigenous communities may control the administration of their people, land, resources, and related programs and policies, through agreements with federal and provincial governments. It is about First Nations taking greater control over and making their own decisions about matters that affect their communities within the Canadian constitutional framework. First Nations have their own governments with responsibilities, structures, resources, and taxation powers similar to other municipal or territorial governments in Canada. These First Nations are guided by their Final Land Claim Agreements, Self-Government Agreements, and Constitutions.” I suppose this would be similar to the Indian Nations in the United States, who are government entities in their own right.

Fort Selkirk was built as a trading post on the Yukon River at the junction of the Pelly River in Canada’s Yukon. For many years it was home to the Selkirk First Nation, also known a Northern Tutchone. The Selkirk First Nation is a First Nation self-government in the Canadian territory, Yukon. “First Nation self-government is a formal structure through which Indigenous communities may control the administration of their people, land, resources, and related programs and policies, through agreements with federal and provincial governments. It is about First Nations taking greater control over and making their own decisions about matters that affect their communities within the Canadian constitutional framework. First Nations have their own governments with responsibilities, structures, resources, and taxation powers similar to other municipal or territorial governments in Canada. These First Nations are guided by their Final Land Claim Agreements, Self-Government Agreements, and Constitutions.” I suppose this would be similar to the Indian Nations in the United States, who are government entities in their own right.

The trading post of Fort Selkirk was the hub of the community, allowing the buying, selling, and trading of  items needed for everyday life. Most of the people lived nearby, but these days, most of its citizens now live in Pelly Crossing, Yukon where the Klondike Highway crosses the Pelly River. The original language of the people was Northern Tutchone. These days, there is an effort to ensure that the language and culture are not lost. Archaeological evidence shows that the site has been in use for at least 8,000 years.

items needed for everyday life. Most of the people lived nearby, but these days, most of its citizens now live in Pelly Crossing, Yukon where the Klondike Highway crosses the Pelly River. The original language of the people was Northern Tutchone. These days, there is an effort to ensure that the language and culture are not lost. Archaeological evidence shows that the site has been in use for at least 8,000 years.

In 1848, Robert Campbell established a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post nearby, and in early 1852, he moved the post to its current location. This caused a lot of resentment due to the interference of the Hudson’s Bay Company with their traditional trade with interior Athabaskan First Nations. So, on August 21, 1852, the Chilkat Tlingit First Nation warriors attacked and looted the post. For a time, after the attack, the fort was in ruins. It was rebuilt about 40 years later and once again became an important supply point along the Yukon River.

The fort was basically abandoned again in the mid-1950s, after the Klondike Highway bypassed it and Yukon River traffic died down. These days it would be considered a ghost town I suppose. Nevertheless, many of the

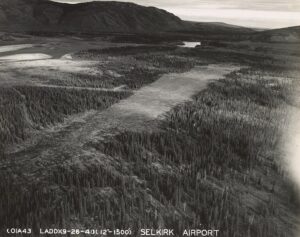

buildings have been restored and the Fort Selkirk Historic Site is owned and managed jointly by the Selkirk First Nation and the Yukon Government’s Department of Tourism and Culture. That doesn’t mean that it has become a tourist hub, because the fact remains that there is no road access to the site. Most visitors get there by boat, though there is an airstrip, Fort Selkirk Aerodrome, at the site. A person would have to have a specific reason for going to the site, or they would be unlikely to make the journey.

buildings have been restored and the Fort Selkirk Historic Site is owned and managed jointly by the Selkirk First Nation and the Yukon Government’s Department of Tourism and Culture. That doesn’t mean that it has become a tourist hub, because the fact remains that there is no road access to the site. Most visitors get there by boat, though there is an airstrip, Fort Selkirk Aerodrome, at the site. A person would have to have a specific reason for going to the site, or they would be unlikely to make the journey.