tons

I’m told that the Sun weighs 2,000 million million million million tons. That if course, sounds very heavy, and I suppose it could be fairly accurate. Nevertheless, for me these questions arise. How do they know the weight of the Sun? Who was it that somehow managed to go out there and weight the Sun? And where did they get a scale big enough to set the Sun on to get this very accurate sounding weight? Ok, I’m being sarcastic, but then again, these are legitimate questions. I’m told that there is a formula they use to figure the mass of a planet.

I’m told that the Sun weighs 2,000 million million million million tons. That if course, sounds very heavy, and I suppose it could be fairly accurate. Nevertheless, for me these questions arise. How do they know the weight of the Sun? Who was it that somehow managed to go out there and weight the Sun? And where did they get a scale big enough to set the Sun on to get this very accurate sounding weight? Ok, I’m being sarcastic, but then again, these are legitimate questions. I’m told that there is a formula they use to figure the mass of a planet.

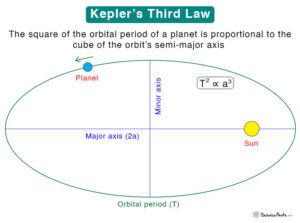

First one has to calculate the mass of the Sun. There are apparently several ways to do so. One way is to use Kepler’s third law: “M = 4r³?²/T²G, where r is the distance between the Earth and the Sun, T is the time it takes for the Earth to orbit the Sun, and G is the gravitational constant. The mass of the Sun is about 2×10³? kg.” Another way is to use the mass formula: “Mass = Density x Volume. The mass of the Sun’s core is estimated to be 3.0 x 10³¹ kg, and the mass of the outer shell is estimated to be 1.1 x 10³¹ kg.” The third way is to “divide the total mass by 1.98855 times 10 to the 30th power.” From what I can see, the common methos is the Kepler’s third law. Once you have that figured, you are ready for the next step…the weight of the Sun.

That process is as complicated as, or nearly as complicated as the methods to figure the mass of the Sun. Apparently, it all has to do with the mass of the Sun, the mass of the Earth, the gravitational pull on the Earth by the Sun, and the distance between the two squared. Or more scientifically written, “The gravitational attraction between the Earth and the sun is G times the sun’s mass times the Earth’s mass, divided by the distance between the Earth and the sun squared. This attraction must be equal to the centripetal force needed to keep the earth in its (almost circular) orbit around the sun.” If that makes perfect sense to you, then you are

likely a better scientist or mathematician than the average person. So even if I could fully understand that process, and I don’t, I still have to ask one question, where is the proof that its true and accurate. I realize that there is no way to definitively prove the weight of the Sun, the Earth, or any other planet, and maybe this is somehow he most accurate guess possible. I don’t know, but maybe they should say that the Sun weighs approximately 2,000 million million million million tons. At least, that would stop such silly questions from people like me.

likely a better scientist or mathematician than the average person. So even if I could fully understand that process, and I don’t, I still have to ask one question, where is the proof that its true and accurate. I realize that there is no way to definitively prove the weight of the Sun, the Earth, or any other planet, and maybe this is somehow he most accurate guess possible. I don’t know, but maybe they should say that the Sun weighs approximately 2,000 million million million million tons. At least, that would stop such silly questions from people like me.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In any war, there are certain weapons, ships, planes, or vehicles that are somewhat, if not totally, feared by the enemy, and World War I was no exception. The Germans has a couple of light cruisers, the Dresden and the Emden. These cruisers were the fastest ships in the German Imperial Navy, capable of traveling at speeds of up to 24.5 knots. They weighed in at 3,600 tons, and they were two of the first German ships to be built with modern steam-turbine engines. The British actually had faster ships, but the Dresden had managed to avoid them…until March 14, 1915, that is. The Dresden was put in service in 1909, and kept very busy. Between August 1, 1914 and March 1915 the Dresden traveled over 21,000 miles.

In the summer of 1914, the Dresden was patrolling the Caribbean Sea. Its assignment was to safeguard German investments and German citizens living abroad in the region. Then, on July 20, during a bitter civil war in Mexico, the Dresden was called upon to give safe passage to Mexican president, Victoriano Huerta, by transporting him and his family as they escaped to Jamaica, where they received asylum from the British government. Then came news from Europe of Austria’s ultimatum to Serbia and the imminent possibility of war. The German’s put the fleet on alert. By the first week of August the nations of Europe were at war. The Dresden was sent to South America to attack British shipping interests there, and it sunk several merchant ships as it traveled to Cape Horn, at the southern tip of Chile. The Dresden eluded the British naval squadron in  the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

the region, commanded by Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. In October, the ship joined Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s German East Asia Squadron at Easter Island in the South Pacific. On November 1, Spee’s squadron, including Dresden, scored a crushing victory over the British in the Battle of Coronel, sinking two cruisers with all hands aboard, including Cradock, who went down with his flagship, Good Hope.

Just five weeks later, the Dresden was the only German ship to escape destruction at the Battle of the Falkland Islands on November 8, when the British light cruisers Inflexible and Invincible, commanded by Sir Doveton Sturdee, sank four of von Spee’s ships. Lost were Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Leipzig and Nurnberg. As a crew member of Dresden wrote later of watching one of the other ships sink, “Each one of us knew he would never see his comrades again, no one on board the cruiser can have had any illusions about his fate.” Then the Dresden escaped under cover of bad weather south of the Falkland Islands.

Dresden consistently avoided capture by the British navy over the next several months, while sinking a number of cargo ships and then seeking refuge in the network of channels and bays in southern Chile. In need of repairs, the Dresden put into an island off the Chilean coast, in Cumberland Bay on March 8th. Captain, Fritz Emil von Luedecke, had decided the repairs were necessary in the wake of such heavy and extended use. Captain von Luedecke sent out many messages asking for fuel in the hopes of reaching any passing coal ships in the area, but the messages were picked up the British ships, Kent and Glasgow six days later. After a  hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.

hurried search, Kent and Glasgow found Dresden. When Kent opened fire, Dresden sent a few shots back, but soon raised the white flag of surrender. They knew they had no chance against the Kent in their current condition. A German representative negotiated a truce with the British sailors to stall for time, and von Luedecke ordered his crew to abandon the ship and scuttle it. Dresden sank slowly at first, then sharply listed to the side. Amid cheers from both the British on board their two ships and the German sailors that had escaped onto land, Dresden disappeared beneath the water, its German ensign flag flying. It was a sad ending to the five year, 21,000-mile career of one of Germany’s most famous World War I commerce-raiding ships.