the congressional limited

Monday, September 6, 1943, was the Labor Day holiday and the Pennsylvania Railroad company had laid on 16-car trains to accommodate the expected high demand. At 4pm, the passenger count on the premier train, the Congressional Limited was at 541 people on the 16 cars, being hauled by PRR GG1 electric locomotive number 4930, scheduled to travel nonstop from Washington’s Union Station to Pennsylvania Station in New York.

Monday, September 6, 1943, was the Labor Day holiday and the Pennsylvania Railroad company had laid on 16-car trains to accommodate the expected high demand. At 4pm, the passenger count on the premier train, the Congressional Limited was at 541 people on the 16 cars, being hauled by PRR GG1 electric locomotive number 4930, scheduled to travel nonstop from Washington’s Union Station to Pennsylvania Station in New York.

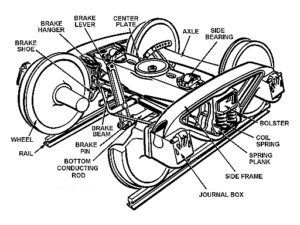

As the train reached Frankford Junction the train derailed in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, killing 79 people and injuring 117 others. As the train passed through the North Philadelphia station, everything seemed to be in order. The train was even coming in a little bit ahead of schedule. It began to slow its speed, but shortly afterward, as it passed a rail yard, workers saw flames coming from a journal box (a hot box) on one of the cars. Jumping into action, they rang the next signal tower at Frankford Junction, but unfortunately, that call came too late. Before the worker who was manning the tower could react, disaster struck as the train passed his signal tower at 6:06 pm traveling at a speed of 56 miles per hour. The journal box on the front of car #7 had seized and an axle snapped, which caught the truck and  catapulted it upwards. The car subsequently struck a signal gantry, which peeled off its roof along the line of windows “like a can of sardines.” From there everything fell apart like a house of cards. Car #8 wrapped itself around the gantry upright in a figure U. The next six cars were scattered at odd angles over the tracks, with only the last two cars remaining undamaged. The scene was one of devastation, with the bodies of the 79 dead lying scattered over the tracks.

catapulted it upwards. The car subsequently struck a signal gantry, which peeled off its roof along the line of windows “like a can of sardines.” From there everything fell apart like a house of cards. Car #8 wrapped itself around the gantry upright in a figure U. The next six cars were scattered at odd angles over the tracks, with only the last two cars remaining undamaged. The scene was one of devastation, with the bodies of the 79 dead lying scattered over the tracks.

Because the derailment happened during wartime, there were a number of servicemen onboard who were on leave. The men immediately jumped into action, helping the injured. Workers from the nearby Cramp’s shipyard arrived with acetylene torches to cut open cars to rescue the injured. That is a long process, that took until the following morning. The rescue work was directed by Mayor Bernard Samuel. The gruesome work of removing the dead was not completed until 24 hours after the accident. The Congressional Limited traveled between Washington DC and New York City, normally making one stop in Newark, New Jersey, covering the 236 miles in 3½ hours at speeds up to 80 miles per hour, which seems fast for the time. All the deaths occurred in cars #7 and #8, and 117 other passengers were injured, some seriously. There were survivors, of course, one of whom was Chinese author Lin Yutang.

The inquiry centered on the journal box on car #7 as the cause of the accident. The railroad mechanics who had inspected and lubricated the box earlier that day swore it had been in good order. Normal practice was for signal towermen to watch passing train wheels for signs of problems and for train crew to look back as trains rounded curves. Somehow, the overheated and eventually burning journal box was missed. How that happened was never explained. Did the towermen and train crew simply become lax in their duties, thinking that nothing ever happened on their train, were they possibly over tired that day, or were the just busy with other tasks. These are questions we will never have answers for, unfortunately.

I always thought that train travel was similar to air travel, and accidents were not very common. Unlike air travel, train derailments are really quite common, mostly because they are like flat tires on cars…they do happen, and depending on how fast you’re going and where you are, it can be a minor delay, or a major problem. Having a flat tire in your own driveway is no big deal, but when a tire explodes on the highway…that’s a major problem. Blowouts have been known to cause terrible accidents and deaths. Now, consider that there are over 170,000 miles of railroad track in the United States. The possibilities suddenly seem endless. The good news is that many of these “derailments” are very minor and bring no injury or death, but that is not always the case. Speed plays a huge role in the outcome of a derailment, and I don’t mean that the train was necessarily speeding, just that it was going faster than the slow, “in the yard” pace.

I always thought that train travel was similar to air travel, and accidents were not very common. Unlike air travel, train derailments are really quite common, mostly because they are like flat tires on cars…they do happen, and depending on how fast you’re going and where you are, it can be a minor delay, or a major problem. Having a flat tire in your own driveway is no big deal, but when a tire explodes on the highway…that’s a major problem. Blowouts have been known to cause terrible accidents and deaths. Now, consider that there are over 170,000 miles of railroad track in the United States. The possibilities suddenly seem endless. The good news is that many of these “derailments” are very minor and bring no injury or death, but that is not always the case. Speed plays a huge role in the outcome of a derailment, and I don’t mean that the train was necessarily speeding, just that it was going faster than the slow, “in the yard” pace.

When high speed trains first came out, they seemed pretty risky, and maybe they were, but it was only because engineers weren’t used to those speeds, and possibly the equipment wasn’t ready for those speeds  either. That would become all to obvious on September 6, 1943, when an apparent defect in an older car attached to the train, combined with the placement of a signal gantry resulted in a deadly accident. The train was called the Congressional Limited and was a newly designed train that carried its passengers through the Northeast corridor at the previously unheard-of speed of 65 miles per hour. The Congressional Limited was traveling between New York City and Washington DC, and had just left Philadelphia. It began to pick up speed as it moved northeast out of the city, The dining car, that had just been added, began to experience axle problems. That day, there were so many customers seeking to ride from Washington to New York that it was decided that another dining car should be added to the train…a car of an older design. Observers near the track reported that the axle of that older car was burning and throwing off sparks. Two miles further down the track, in Frankford Junction, Pennsylvania, the axle fell off, derailing the dining car.

either. That would become all to obvious on September 6, 1943, when an apparent defect in an older car attached to the train, combined with the placement of a signal gantry resulted in a deadly accident. The train was called the Congressional Limited and was a newly designed train that carried its passengers through the Northeast corridor at the previously unheard-of speed of 65 miles per hour. The Congressional Limited was traveling between New York City and Washington DC, and had just left Philadelphia. It began to pick up speed as it moved northeast out of the city, The dining car, that had just been added, began to experience axle problems. That day, there were so many customers seeking to ride from Washington to New York that it was decided that another dining car should be added to the train…a car of an older design. Observers near the track reported that the axle of that older car was burning and throwing off sparks. Two miles further down the track, in Frankford Junction, Pennsylvania, the axle fell off, derailing the dining car.

The derailment happened just as the train was approaching a signal gantry…a steel structure built right next to  the tracks. The gantry sliced right through the dining car, instantly killing many of the passengers on that car. Seven more cars were pulled off the tracks by the dining car. In addition to the 79 people who lost their lives, almost 100 more were seriously injured. The train was carrying 541 passengers that day, many of whom were World War II soldiers returning from leave…probably the reason that an additional dining car was needed. A subsequent inquiry placed more of the blame on the location of the signal gantry than the decision to add the old dining car to the speedy new Congressional Limited, which doesn’t make sense to me, because if the axel hadn’t fallen off, the derailment would not have happened at all, and the gantry had been there for a long time.

the tracks. The gantry sliced right through the dining car, instantly killing many of the passengers on that car. Seven more cars were pulled off the tracks by the dining car. In addition to the 79 people who lost their lives, almost 100 more were seriously injured. The train was carrying 541 passengers that day, many of whom were World War II soldiers returning from leave…probably the reason that an additional dining car was needed. A subsequent inquiry placed more of the blame on the location of the signal gantry than the decision to add the old dining car to the speedy new Congressional Limited, which doesn’t make sense to me, because if the axel hadn’t fallen off, the derailment would not have happened at all, and the gantry had been there for a long time.