starvation

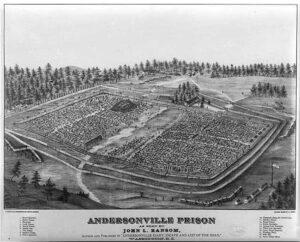

Andersonville POW camp was a Civil War era POW camp that was heavily fortified. It was run by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes when the war was over. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman. The prison is located near Andersonville, Georgia, and today is a national historic site that is also known as Camp Sumpter. To me, its design had a somewhat unusual layout in that it had what is called a “Dead Line”. Some people might know what that is, but any prisoner who dared to tough it, much less try to cross it, found out very quickly what it was, because they were shot instantly…no questions asked. For that reason, prisoners rarely escaped from Andersonville Prison. The “dead line” was set up by the Confederate forces guarding the prison, to assist in prisoner control. The prison operated between February 25, 1864, and May 9, 1864. During that time, a total of 4,588 patients visited the Andersonville prison hospital, and 1,026 never left there alive.

Andersonville POW camp was a Civil War era POW camp that was heavily fortified. It was run by Captain Henry Wirz, who was tried by a military tribunal on charges of war crimes when the war was over. The trial was presided over by Union General Lew Wallace and featured chief Judge Advocate General (JAG) prosecutor Norton Parker Chipman. The prison is located near Andersonville, Georgia, and today is a national historic site that is also known as Camp Sumpter. To me, its design had a somewhat unusual layout in that it had what is called a “Dead Line”. Some people might know what that is, but any prisoner who dared to tough it, much less try to cross it, found out very quickly what it was, because they were shot instantly…no questions asked. For that reason, prisoners rarely escaped from Andersonville Prison. The “dead line” was set up by the Confederate forces guarding the prison, to assist in prisoner control. The prison operated between February 25, 1864, and May 9, 1864. During that time, a total of 4,588 patients visited the Andersonville prison hospital, and 1,026 never left there alive.

According to former prisoner, enlisted soldier John Levi Maile, “It consisted of a narrow strip of board nailed to a row of stakes, about four feet high.” The “dead line” completely encircled Andersonville. Soldiers were told to “shoot any prisoner who touches the ‘dead line'” “It was the standing order to the guards,” Maile explained. “A sick prisoner inadvertently placing his hand on the “dead line” for support… or anyone touching it with suicidal intent, would be instantly shot at, the scattering balls usually striking other than the one aimed at.” It was a risk the prisoners took if they chose to be anywhere near the “dead line” at all. Prisoner Prescott Tracy worked as a clerk in the Andersonville hospital. He said, “I have seen one hundred and fifty bodies waiting passage to the “dead house,” to be buried with those who died in hospital. The average of deaths through the earlier months was thirty a day; at the time I left, the average was over one hundred and thirty, and one day the record showed one hundred and forty-six.” The major threats in the prison camp were diarrhea, dysentery, and scurvy.

A sergeant major in the 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, Robert H. Kellogg what he saw when he entered the camp as a prisoner on May 2, 1864, “As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us. Before us were forms that had once been active and erect…stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness. “Can this be hell?” “God protect us!” and all thought that he alone could bring them out alive from so terrible a place. In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating. The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then.”

After hearing the accounts of men who had the misfortune of being incarcerated in this horrific POW camp, I

wondered if there might have been some changes had the camp been run in more modern times. Of course, there is no guarantee of that, since there has been mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in all wars, and the treatment ultimately falls on the people running the camp and the soldiers monitoring the prisoners. It is, however, a sad state of affairs when prisoners are starved, beaten, frozen, and otherwise mistreated in these camps. The point is to hold them, not murder them.

wondered if there might have been some changes had the camp been run in more modern times. Of course, there is no guarantee of that, since there has been mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in all wars, and the treatment ultimately falls on the people running the camp and the soldiers monitoring the prisoners. It is, however, a sad state of affairs when prisoners are starved, beaten, frozen, and otherwise mistreated in these camps. The point is to hold them, not murder them.

In reality, they gave science a bad name. The calculations made by German scientists before the invasion of Leningrad was launched in September of 1941, estimated that as many as 30 million Russian civilians would succumb to starvation. Hitler’s plan was to annihilate the Russian population and establish new German colonies in Eastern Europe. Hitler had a very specific idea of “the perfect race” and he would stop at nothing to achieve his goal.

In reality, they gave science a bad name. The calculations made by German scientists before the invasion of Leningrad was launched in September of 1941, estimated that as many as 30 million Russian civilians would succumb to starvation. Hitler’s plan was to annihilate the Russian population and establish new German colonies in Eastern Europe. Hitler had a very specific idea of “the perfect race” and he would stop at nothing to achieve his goal.

The people of Leningrad would experience Hitler’s cold German indifference to suffering firsthand. I suppose “German indifference” isn’t totally fair, because many of the German people were against the cruelty Hitler was so comfortable with. When the city was surrounded by September 1941, the Axis forces chose not to close in and engage in costly urban fighting, but to pound Leningrad from a safe distance and let hunger do the rest. They planned to block all transportation of vehicles in and out of the city, until all food ran out, and the people died from starvation.

Hitler’s plan left out one thing…a Surrender Option. The people could not surrender and live. They wanted then to die, and that was going to be their only option. Hitler’s direct order was to ignore the offer to surrender, saying “Requests for surrender resulting from the city’s encirclement will be denied, since the problem of relocating and feeding the population cannot and should not be solved by us.”

Hitler was ruthless. The city’s water and food supplies were cut off, and extreme famine soon set in. The siege of Leningrad began on September 8, 1941, and ended after a grueling two-year period on January 27, 1944. Yes, the siege produced starvation and disease, but Hitler took it a step further…to psychological torment. On Hitler’s orders, Leningrad suffered a daily barrage of artillery attacks from the German and Finnish forces that encircled it. The people were already starving, and lack of food or drink for long periods of time, can make something like an artillery attack, be that much more unsettling…even to the point of more than terror. They are dealing with gnawing hunger, and the terror of wondering if the artillery will hit them, and they should be, because Hitler would not care if he hit a civilian, accidently or on purpose. The people had no recourse, and no way out. After 872 days of starvation, disease, and the artillery attacks, the citizens of Leningrad…the ones who

were left anyway, were freed, but to what. Their city had been overtaken, many had family members who had died, their businesses were gone, their homes were gone…they had lost it all. In total, roughly 1.5 million people were killed during the siege of Leningrad while some 1.4 million were evacuated. I’m sure Hitler was still disappointed with the outcome, because he wanted them all dead.

were left anyway, were freed, but to what. Their city had been overtaken, many had family members who had died, their businesses were gone, their homes were gone…they had lost it all. In total, roughly 1.5 million people were killed during the siege of Leningrad while some 1.4 million were evacuated. I’m sure Hitler was still disappointed with the outcome, because he wanted them all dead.

Being Jewish during the Holocaust meant doing whatever it took to survive. For some, that means hiding in walls or changing one’s identity, then so be it. Still, there were other Jews who had no way of doing either of these things, so they had to make due with what they had. The path to freedom and life was a difficult one, no matter what path they chose. There were close calls, starvation, fear, and a lot of quiet. Two families decided that they had no choice, but to take refuge in a hayloft over a pigsty offered by the owner, Francisca Halamajowa, a kindly Polish Catholic woman, and her daughter, Helena, who protected these families.

Being Jewish during the Holocaust meant doing whatever it took to survive. For some, that means hiding in walls or changing one’s identity, then so be it. Still, there were other Jews who had no way of doing either of these things, so they had to make due with what they had. The path to freedom and life was a difficult one, no matter what path they chose. There were close calls, starvation, fear, and a lot of quiet. Two families decided that they had no choice, but to take refuge in a hayloft over a pigsty offered by the owner, Francisca Halamajowa, a kindly Polish Catholic woman, and her daughter, Helena, who protected these families.

The Malkin and Kinder families went into hiding in 1942, just before the town’s Jewish ghetto was liquidated, but unfortunately, after 4 year old Fay Malkin’s father and others were killed in an old brick factory nearby. Years later in 2011, Fay Malkin told of the heroic acts of Halamajowa. Fay Malkin almost died shortly before her 5th birthday, while hiding in that hayloft. She told the Holocaust remembrance gathering at UJA-Federation of New York on May 3rd: “Hitler didn’t win, we’re here.” Malkin tells of the 20 months that the family and two other families stayed hidden in order to stay alive…and to protect their protectors, who would have also lost their lives if they were caught.

The families worried that 4-year-old Fay would give them away with her crying. The little girl promised not to cry, but that is really a lot to ask of a little girl. Malkin couldn’t control herself once in the hayloft. After trying many other approaches, the adults finally made the excruciating decision to poison little Fay in order to save the rest. Malkin would have almost certainly been killed, if they were discovered. Malkin said her memory of the incident is faint, but she remembers pushing out the pill put in her mouth. Just before she was put in a bag to be buried, a doctor who was among those hiding felt a slight pulse. She was saved. “I became the miracle child,” she said. Having lived with the story her whole life, Fay smiled when she said that her crying after that was controlled by pillows. The families were saved, not only because of the kindness and courage of their fellow townspeople, but by the miracle of a little child that didn’t die. I realize that the fact that little Fay Malkin lived through the attempted poisoning may not seem like something that saved the families, but in reality, how could they have lived with themselves? Yes, they would have been alive, but they would have been almost as bad as the Nazis who were trying to kill them.

The Malkin family lived in Sokal, then part of Poland…now in Ukraine. Before World War II, there were 6,000 Jews in Sokal. By the end of the war, only about 30 had survived, and half of them were sheltered by Halamajowa. For 20 months, the families stayed in that tiny hayloft…never daring to leave or even make a sound. Halamajowa and her daughter, Helena, risked their lives by feeding them surreptitiously and otherwise helping them, all the while disguising their actions from her neighbors and the occupying German army. In July 1944, the town was liberated by the Soviets. When the Malkin and Kindler families were finally able to come down from the hayloft, they learned that Halamajowa had also been sheltering another Jewish family in a hole dug under her kitchen floor. What these two women did was above and beyond expectation, and very brave.

Of course, most Jews never spoke of the experience. They didn’t want to get anyone in trouble, and their  protectors felt the same way. They didn’t trust the government, even with the war over. Halamajowa died in Russia in 1960…never having revealed her secrets. Nevertheless, in 1986 she was honored at Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile…a fitting title. In 2007, Malkin, Maltz, and several others from the hayloft and celler families, returned to Sokal. The trip was part of a film project that led to No. 4 Street of Our Lady. A basis for the film was the diary kept by Fay’s cousin, Moshe Maltz. Malkin said it was important but highly emotional going back to Sokal, especially seeing where her father was killed. Included in the group traveling there were the two granddaughters of Halamajowa, who now live in Connecticut. I’m sure it was very emotional.

protectors felt the same way. They didn’t trust the government, even with the war over. Halamajowa died in Russia in 1960…never having revealed her secrets. Nevertheless, in 1986 she was honored at Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile…a fitting title. In 2007, Malkin, Maltz, and several others from the hayloft and celler families, returned to Sokal. The trip was part of a film project that led to No. 4 Street of Our Lady. A basis for the film was the diary kept by Fay’s cousin, Moshe Maltz. Malkin said it was important but highly emotional going back to Sokal, especially seeing where her father was killed. Included in the group traveling there were the two granddaughters of Halamajowa, who now live in Connecticut. I’m sure it was very emotional.

When an evil empire, such as Hitler’s regime in Nazi Germany, decides to rule the world, they begin to take over neighboring nations…by any means possible. If the nation is too weak to fight, it is easy, but if the nation can fight it becomes much harder to succeed. Nevertheless, they always seem to find a way, if they are determined enough. And Hitler was nothing, if not determined. The Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in late September, and surrounded Leningrad soon after. The months that followed, found the people of the city trying to establish supply lines from the Soviet interior and attempting to evacuate its citizens. It was a tough process and they often found themselves using a hazardous “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga. A successful land corridor was finally created in January 1943, and the Red Army finally managed to drive off the Germans the following year. Nevertheless, all that took time, and in the end, the siege lasted nearly 900 days and resulted in the deaths of more than 1 million Soviet civilians.

When an evil empire, such as Hitler’s regime in Nazi Germany, decides to rule the world, they begin to take over neighboring nations…by any means possible. If the nation is too weak to fight, it is easy, but if the nation can fight it becomes much harder to succeed. Nevertheless, they always seem to find a way, if they are determined enough. And Hitler was nothing, if not determined. The Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in late September, and surrounded Leningrad soon after. The months that followed, found the people of the city trying to establish supply lines from the Soviet interior and attempting to evacuate its citizens. It was a tough process and they often found themselves using a hazardous “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga. A successful land corridor was finally created in January 1943, and the Red Army finally managed to drive off the Germans the following year. Nevertheless, all that took time, and in the end, the siege lasted nearly 900 days and resulted in the deaths of more than 1 million Soviet civilians.

The German and Finnish forces besieged Lenin’s namesake city after their spectacular initial advance during Operation Barbarossa in the summer of 1941. Nevertheless, it was not going to be an easy task to bring the Soviet people into submission. A German Army Group struggled against stubborn Soviet resistance to isolate and seize the city before the onset of winter. The fighting was heaviest during August. German forces reached the city’s suburbs and the shores of Lake Ladoga, severing Soviet ground communications with the city. In  November 1941, Soviet forces repelled a renewed German offensive and clung to tenuous resupply routes across the frozen waters of Lake Ladoga. After that, German and Soviet strategic attention shifted to other more critical sectors of the Eastern Front, and Leningrad…its defending forces and its large civilian population…endured an 880 day siege of unparalleled severity and hardship. I simply can’t imagine the cruelty of a regime that would let a million people starve to death to obtain power. Despite desperate Soviet use of an “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga to resupply its three million encircled soldiers and civilians and to evacuate one million civilians, over one million civilians perished during that bitter siege. Another 300,000 Soviet soldiers died defending the city or attempting to end the siege. In January 1943, Soviet forces opened a narrow land corridor into the city through which vital rations and supplies again flowed. But it was not until January 1944, that the Red Army successes in other front sectors enable the Soviets to end the siege. By this time, the besieging German forces were so weak that renewed Soviet attacks drove them away from the city and from Soviet soil. Determination simply wasn’t enough to win that victory for Hitler.

November 1941, Soviet forces repelled a renewed German offensive and clung to tenuous resupply routes across the frozen waters of Lake Ladoga. After that, German and Soviet strategic attention shifted to other more critical sectors of the Eastern Front, and Leningrad…its defending forces and its large civilian population…endured an 880 day siege of unparalleled severity and hardship. I simply can’t imagine the cruelty of a regime that would let a million people starve to death to obtain power. Despite desperate Soviet use of an “ice and water road” across Lake Ladoga to resupply its three million encircled soldiers and civilians and to evacuate one million civilians, over one million civilians perished during that bitter siege. Another 300,000 Soviet soldiers died defending the city or attempting to end the siege. In January 1943, Soviet forces opened a narrow land corridor into the city through which vital rations and supplies again flowed. But it was not until January 1944, that the Red Army successes in other front sectors enable the Soviets to end the siege. By this time, the besieging German forces were so weak that renewed Soviet attacks drove them away from the city and from Soviet soil. Determination simply wasn’t enough to win that victory for Hitler.

After November 1941, possession of Leningrad held only symbolic significance. In holding the “ice and water road” the Soviets were able to bring in enough supplies to stave of the ongoing starvation, so the siege has a  little less effect. The Germans maintained their siege with a single army, and defending Soviet forces numbered less than 15 percent of their total strength on the German-Soviet front. The Leningrad sector was clearly of secondary importance, and the Soviets raised the siege only after the fate of German arms had been decided in more critical front sectors. Despite its diminished strategic significance, the suffering and sacrifices of Leningrad’s dwindling population and defending forces inspired the Soviet war effort as a whole. No nation can lose that many people and not feel its impact. The siege ended on January 27, 1944, but I don’t think the people felt that it was such a big victory, considering the loss of life.

little less effect. The Germans maintained their siege with a single army, and defending Soviet forces numbered less than 15 percent of their total strength on the German-Soviet front. The Leningrad sector was clearly of secondary importance, and the Soviets raised the siege only after the fate of German arms had been decided in more critical front sectors. Despite its diminished strategic significance, the suffering and sacrifices of Leningrad’s dwindling population and defending forces inspired the Soviet war effort as a whole. No nation can lose that many people and not feel its impact. The siege ended on January 27, 1944, but I don’t think the people felt that it was such a big victory, considering the loss of life.

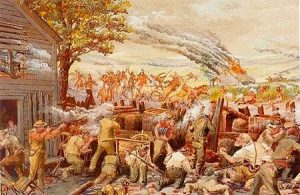

As the pioneers headed west, there were various disputes over ownership of the lands they were settling into. The Native American people did not think that they should have to surrender their lands to the White Man, but it seemed that they had no choice. Still, there were some Native Americans who refused to be pushed around by the government. On August 17, 1862, violence erupted in Minnesota as desperate Dakota Indians attacked white settlements along the Minnesota River. This was a fight that the Dakota Indians would eventually lose. They were no match for the US military, and six weeks later, it was over.

As the pioneers headed west, there were various disputes over ownership of the lands they were settling into. The Native American people did not think that they should have to surrender their lands to the White Man, but it seemed that they had no choice. Still, there were some Native Americans who refused to be pushed around by the government. On August 17, 1862, violence erupted in Minnesota as desperate Dakota Indians attacked white settlements along the Minnesota River. This was a fight that the Dakota Indians would eventually lose. They were no match for the US military, and six weeks later, it was over.

The Dakota Indians were often referred to as the Sioux, which I did not know was a derogatory name derived from part of a French word meaning “little snake.” It almost makes it seem like they were talking badly about them to their face, but so they couldn’t understand it. The government treated the Dakota poorly, and the Dakota saw their hunting lands dwindling  down, and apparently the provisions that the government promised to supply, rarely arrived. And now, to top it off, a wave of white settlers surrounded them too. To make matters worse, the summer of 1862 had been a harsh one, and cutworms had destroyed much of the crops. The Dakota were starving.

down, and apparently the provisions that the government promised to supply, rarely arrived. And now, to top it off, a wave of white settlers surrounded them too. To make matters worse, the summer of 1862 had been a harsh one, and cutworms had destroyed much of the crops. The Dakota were starving.

On August 17, the situation exploded when four young Dakota warriors returning from an unsuccessful hunt, stopped to steal some eggs from a white settlement. The were caught and they picked a fight with the hen’s owner. The encounter turned tragic when the Dakotas killed five members of the family. Now, the Dakota knew that they would be attacked. Dakota leaders, knew that war was at hand, so they seized the initiative. Led by Taoyateduta, also known as Little Crow, the Dakota attacked local agencies and the settlement of New  Ulm. Over 500 white settlers lost their lives along with about 150 Dakota warriors.

Ulm. Over 500 white settlers lost their lives along with about 150 Dakota warriors.

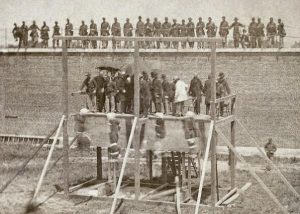

President Abraham Lincoln dispatched General John Pope, fresh from his defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run, Virginia. Pope was to organize the Military Department of the Northwest. Some of the Dakota immediately fled Minnesota for North Dakota, but more than 2,000 were rounded up and over 300 warriors were sentenced to death. President Lincoln commuted most of their sentences, but on December 26, 1862, 38 Dakota men were executed at Mankato, Minnesota. It was the largest mass execution in American history, and it was all because they were starving, and had no hope of living through that year.