sioux indians

When Colorado Governor John Evans was looking to win a seat in the United States Senate, he made a bold, but unwise decision to attempt to remove all Native American activity in eastern Colorado Territory. On June 24, 1864, he warned that all peaceful Indians in the region must report to the Sand Creek reservation or risk being attacked. It was truly a halfhearted offer of sanctuary, with an ulterior motive. Evans then made one bad decision after another, when he issued a second proclamation that invited white settlers to indiscriminately “kill and destroy all…hostile Indians.” At the same time, Evans began creating a temporary 100-day militia force to wage war on the Indians. He placed the new regiment under the command of Colonel John Chivington, another ambitious man who hoped to gain high political office by fighting Indians.

When Colorado Governor John Evans was looking to win a seat in the United States Senate, he made a bold, but unwise decision to attempt to remove all Native American activity in eastern Colorado Territory. On June 24, 1864, he warned that all peaceful Indians in the region must report to the Sand Creek reservation or risk being attacked. It was truly a halfhearted offer of sanctuary, with an ulterior motive. Evans then made one bad decision after another, when he issued a second proclamation that invited white settlers to indiscriminately “kill and destroy all…hostile Indians.” At the same time, Evans began creating a temporary 100-day militia force to wage war on the Indians. He placed the new regiment under the command of Colonel John Chivington, another ambitious man who hoped to gain high political office by fighting Indians.

The Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe Indians of eastern Colorado had no idea of the political maneuverings of the White Man. Although some bands had violently resisted white settlers in years past, by the autumn of 1864 many Indians were becoming more receptive to Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle’s argument that they must make peace. Black Kettle had recently returned from a visit to Washington, DC, where President Abraham Lincoln had given him a huge American flag of which Black Kettle was very proud. He had seen the vast numbers of the white people and their powerful machines. The Indians, Black Kettle argued, must make peace or be crushed.

Word of Governor Evans’ June 24 offer of sanctuary was not well received by many of the Indians, most of whom still distrusted the White Man and were unwilling to give up the fight. Only Black Kettle and a few of the  lesser chiefs took Evans up on his offer of amnesty. Evans and Chivington were reluctant to see hostilities further abate before they had won a glorious victory, so they weren’t overjoyed that Black Kettle and his people accepted the offer. Nevertheless, they grudgingly promised Black Kettle that his people would be safe, if they came to Fort Lyon in eastern Colorado. In November 1864, the Indians reported to the fort as requested. Major Edward Wynkoop, the commanding federal officer, told Black Kettle to settle his band about 40 miles away on Sand Creek, where he promised they would be safe.

lesser chiefs took Evans up on his offer of amnesty. Evans and Chivington were reluctant to see hostilities further abate before they had won a glorious victory, so they weren’t overjoyed that Black Kettle and his people accepted the offer. Nevertheless, they grudgingly promised Black Kettle that his people would be safe, if they came to Fort Lyon in eastern Colorado. In November 1864, the Indians reported to the fort as requested. Major Edward Wynkoop, the commanding federal officer, told Black Kettle to settle his band about 40 miles away on Sand Creek, where he promised they would be safe.

Unfortunately, Wynkoop could not control John Chivington, and John Chivington was not inclined to honor the promise of safety. By November, the 100-day enlistment of the soldiers in his Colorado militia was nearly up, and Chivington hadn’t killed any of the Indians. With his political stock falling rapidly, and he seemed almost insane in his desire to kill Indians. “I long to be wading in gore!” he is said to have proclaimed at a dinner party. In his demented state, Chivington apparently decided that it did not matter whether he killed peaceful or hostile Indians. In his mind, Black Kettle’s village on Sand Creek became a legitimate and easy target, and he assumed that no one would ever know the difference.

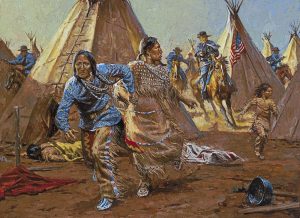

Chivington led 700 men, many of them drunk, in a daybreak raid on Black Kettle’s peaceful village on November 29, 1864. Most of the Cheyenne warriors were away hunting. In the horrific hours that followed, Chivington and his men brutally slaughtered 105 women and children and killed 28 men. The soldiers scalped and mutilated the corpses, carrying body parts back to display in Denver as trophies. Somehow, Black Kettle and a number of other Cheyenne managed to escape. Chivington’s treachery would not go unnoticed as he had supposed, and in the following months, the nation learned of the horror of Sand Creek. Many Americans were

horrified and disgusted. Chivington and his soldiers had left the military and were beyond reach of a court martial. Still, Chivington’s horrific acts killed any chance of realizing his political ambitions, and he spent the rest of his inconsequential life wandering the West. Evans also paid a great price for the scandal. He was forced to resign as governor and his hopes of holding political office were dashed. Evans went on to a successful and lucrative career building and operating Colorado railroads, however. I suppose time can make people forget wrongs done, whether they should be forgotten or not.

horrified and disgusted. Chivington and his soldiers had left the military and were beyond reach of a court martial. Still, Chivington’s horrific acts killed any chance of realizing his political ambitions, and he spent the rest of his inconsequential life wandering the West. Evans also paid a great price for the scandal. He was forced to resign as governor and his hopes of holding political office were dashed. Evans went on to a successful and lucrative career building and operating Colorado railroads, however. I suppose time can make people forget wrongs done, whether they should be forgotten or not.

The Indian tribes didn’t usually have much use for the White Man, especially the ones who worked for the government. It seemed all they wanted to do was to herd the Indians onto the reservations and take away their lands, culture, and their language. This made the majority of Indians pretty angry, but President Calvin Coolidge was different than most government people. It wasn’t a matter of what he was able to accomplish, but rather what he wished he could accomplish, and maybe what he set the stage for…and mostly what the Indians knew was in his heart.

The Indian tribes didn’t usually have much use for the White Man, especially the ones who worked for the government. It seemed all they wanted to do was to herd the Indians onto the reservations and take away their lands, culture, and their language. This made the majority of Indians pretty angry, but President Calvin Coolidge was different than most government people. It wasn’t a matter of what he was able to accomplish, but rather what he wished he could accomplish, and maybe what he set the stage for…and mostly what the Indians knew was in his heart.

President Coolidge had made it very clear that, on personal moral grounds, he sincerely regretted the state of poverty to which many Indian tribes had sunk after decades of legal persecution and forced assimilation had been forced upon them. Coolidge made a public policy toward Indians, that included the Indian Citizen Act of 1924, which granted automatic United States citizenship to all American tribes, something that made perfect sense, since they had been here longer than the nation had existed. Nevertheless, during his two terms in office, while Coolidge  presented a public image as a strong proponent of tribal rights, the United States government policies of forced assimilation remained in full swing during his administration. At this time, all Indian children were placed in federally funded boarding schools in an effort to familiarize them with white culture and train them in marketable skills. During their schooling, they were separated from their families and stripped of their native language and culture, something that should never have happened, and something that has since been changed.

presented a public image as a strong proponent of tribal rights, the United States government policies of forced assimilation remained in full swing during his administration. At this time, all Indian children were placed in federally funded boarding schools in an effort to familiarize them with white culture and train them in marketable skills. During their schooling, they were separated from their families and stripped of their native language and culture, something that should never have happened, and something that has since been changed.

While not able to fix all the wrongs done to the Indians, Coolidge was still considered a friend of the Indians. In 1927, he planned a trip to the Black Hills region of North Dakota. In anticipation of the trip, the Sioux County Pioneer newspaper reported that a Sioux elder named Chauncey Yellow Robe, a descendant of Sitting Bull and an Indian school administrator, had suggested that Coolidge be inducted into the tribe. The article stated that  Yellow Robe graciously offered the president a “most sincere and hearty welcome” and hoped that Coolidge and his wife would enjoy “rest, peace, quiet and friendship among us.” Calvin Coolidge was very pleased at the offer, and decided to accept. This was not something that was offered to many people, so it was a great honor. The Sioux County Pioneer newspaper of North Dakota reported that on June 23, 1927 President Calvin Coolidge would be “adopted” into a Sioux tribe at Fort Yates on the south central border of North Dakota. At the Sioux ceremony in 1927, photographers captured Coolidge, in suit and tie, as he was given a grand ceremonial feathered headdress by Sioux Chief Henry Standing Bear and officially declared an honorary tribal member.

Yellow Robe graciously offered the president a “most sincere and hearty welcome” and hoped that Coolidge and his wife would enjoy “rest, peace, quiet and friendship among us.” Calvin Coolidge was very pleased at the offer, and decided to accept. This was not something that was offered to many people, so it was a great honor. The Sioux County Pioneer newspaper of North Dakota reported that on June 23, 1927 President Calvin Coolidge would be “adopted” into a Sioux tribe at Fort Yates on the south central border of North Dakota. At the Sioux ceremony in 1927, photographers captured Coolidge, in suit and tie, as he was given a grand ceremonial feathered headdress by Sioux Chief Henry Standing Bear and officially declared an honorary tribal member.