shipwrecks

Shipwrecks have always intrigued me. Of course, you always hope that everyone got out alive, but the unfortunate truth is that usually that is not the case. Most shipwrecks sink to the bottom of the ocean, and often it takes years to even fins them. That was not the case with the SS Ayrfield, as well as a couple of other ships that “sank” in plain sight.

Shipwrecks have always intrigued me. Of course, you always hope that everyone got out alive, but the unfortunate truth is that usually that is not the case. Most shipwrecks sink to the bottom of the ocean, and often it takes years to even fins them. That was not the case with the SS Ayrfield, as well as a couple of other ships that “sank” in plain sight.

The SS Ayrfield was built in 1911, and it really didn’t sink. The plan was for it to be decommissioned and scrapped. The SS Ayrfield’s fate was sealed. She had served faithfully for 60 years, having been built in Scotland and sailed to Australia. She was used as a transport supply boat to US troops in the Pacific in World War II, and then retired. She was then used to run coal from Newcastle to Sydney for the rest of her working life. She was finally sent to Homebush Bay, which is where the old marine wrecking yards were. Ships didn’t come back from Homebush Bay. That feels a little sad to me. The plan was to scrap the ship, but that wasn’t exactly what happened.

As the ships sat rusting, waiting for the final scrapping, somehow it just didn’t happen. As they sat there, their insides slowly became completely colonized by mangrove trees. Branches and bark replaced the railings and ropes. The trees have taken root and as they have grown, they have created a giant leafy dome over the slowly disappearing hull. The ships have become known as the “Floating Forest” for obvious reasons, and just like a forest, their beauty is amazing.

Homebush Bay is actually home to the remains of the SS Ayrfield, as well as her neighbors, SS Mortlake Bank, steam tugboat SS Heroic, and boom defense vessel HMAS Karangi, all of which were broken up in the early 1970s. It is thought that there may be as many as seven ships in the bay. They now lie near the south-western shore of the bay, and they are completely visible from land and the hundreds of homes just a short distance away. Some people consider the ship graveyard, a little creepy, but since these weren’t sinkings with a loss of life, I think they are very cool.

Unfortunately, during the 20th century, Homebush Bay was a heavy industry center, home to many industrial facilities. When industrial operations scaled down, the bay became a dumping ground for a large range of unwanted material…from waste to broken up ships, even toxic industrial waste. Union Carbide had manufactured chemicals, including Agent Orange, on the site and dioxins produced as a byproduct were buried in landfill or left in drums. The area has been in the process of being reclaimed, but fishing is prohibited, and I would not want to go in the water. It just doesn’t seem safe…even if it is beautiful.

Whenever a ship sinks, it takes with it a lot of gear, personal effects, and sometimes treasures. These days, they send in the submarines, or rather the mini submarines to salvage whatever they can, find out what caused the sinking, and sometimes to aid in raising the ship to the surface. In times past, when a ship went down, it could easily be lost forever, or at least until more modern times when they could finally find it again.

Whenever a ship sinks, it takes with it a lot of gear, personal effects, and sometimes treasures. These days, they send in the submarines, or rather the mini submarines to salvage whatever they can, find out what caused the sinking, and sometimes to aid in raising the ship to the surface. In times past, when a ship went down, it could easily be lost forever, or at least until more modern times when they could finally find it again.

When the Vasa, an amazingly beautiful Swedish warship that sank on its maiden voyage, 1400 yards into its voyage sat in the harbor for years. The did manage to get the cannon from it right away, but everything else sat underwater until the 1950s, when they had a better way to salvage it. When the world’s first completely covered underwater diving suit was invented around 1715, it consisted of an airtight oak barrel. The suit was used mainly for salvage operations of shipwrecks. I wonder what they could have done with Vasa using that. Vasa wasn’t in dangerously deep water, and could have been accessed easily today, but they just didn’t have the equipment.

The cross between a diving bell and standard diving dress is rather interesting. I wonder if the barrel design John Lethbridge used in 1715 was seriously difficult to move in. It reminds me a of a comical space suit, but I guess it served its purpose. However odd it is, it was the first underwater diving suit, and it is currently located in the Cité de la Mer, a maritime museum in Cherbourg, France.

Lethbridge came up with the idea for his diving suit while working for the East India Company as a salvager. The barrel was airtight, so the diver was protected and safe. The barrel was six feet in length, and the diver had little control of it once it was lowered into the water. The diver had to lay flat on his stomach once the barrel. The barrel had two airtight holes on the sides for the diver’s hands and a hole with glass in the front for use as the diver’s viewing window. During trials, Lethbridge demonstrated that the suit enabled divers to stay 12 fathoms (a unit of length equal to six feet) underwater for at least 30 minutes at a time. That was hard for  me to figure out, until I read that once the diver comes out of the water after 30 minutes, the crew pumped fresh air into the suit through a vent using bellows. At the same time, the used air was let out through another vent. Then, with the fact that the barrel was airtight, the diver was good for another 30 minutes. It wasn’t perfect, but it was much further along than salvage operations had been before it. The suit, while odd and very primitive was an immediate success. It was used mostly to retrieve material from shipwrecks. During Lethbridge’s first salvage…the maiden voyage of the diving suit, as it were, Lethbridge recovered 25 chests of silver and 65 cannons! I would call that a definite success.

me to figure out, until I read that once the diver comes out of the water after 30 minutes, the crew pumped fresh air into the suit through a vent using bellows. At the same time, the used air was let out through another vent. Then, with the fact that the barrel was airtight, the diver was good for another 30 minutes. It wasn’t perfect, but it was much further along than salvage operations had been before it. The suit, while odd and very primitive was an immediate success. It was used mostly to retrieve material from shipwrecks. During Lethbridge’s first salvage…the maiden voyage of the diving suit, as it were, Lethbridge recovered 25 chests of silver and 65 cannons! I would call that a definite success.

I was listening to a book recently about shipwrecks on the Great Lakes and a thought came to my mind that really made me quite sad…though definitely not as sad as when I consider the loss of life that took place in those many wrecks. My Uncle Bill Spencer told me years ago that the Great Lakes are littered with ships that were lost in some of the worst storms on the lakes. In fact, he told me that if you fly over Lake Superior, which is the lake near where he lived most of his life, you could actually see the ships on the bottom of the lake. That thought always made me want to charter a small plane and go see for myself.

I was listening to a book recently about shipwrecks on the Great Lakes and a thought came to my mind that really made me quite sad…though definitely not as sad as when I consider the loss of life that took place in those many wrecks. My Uncle Bill Spencer told me years ago that the Great Lakes are littered with ships that were lost in some of the worst storms on the lakes. In fact, he told me that if you fly over Lake Superior, which is the lake near where he lived most of his life, you could actually see the ships on the bottom of the lake. That thought always made me want to charter a small plane and go see for myself.

Shipwrecks aside, the book told of the different reasons that ships went down, and how the safety regulations were often extremely inadequate. From not enough lifeboats, to lifejackets that were stored to far from the posts to be reached, to companies who regularly pressured their  captains to take their ships out in terrible storms, the life of the sea was very dangerous. Of course, there are still shipwrecks today, although the last sinking on the Great Lakes was on November 10, 1975, when the SS Edmond Fitzgerald went down in a horrible November gale. With more recent safety regulations, the Great Lakes have been able to stave off shipwrecks in the last 45 years.

captains to take their ships out in terrible storms, the life of the sea was very dangerous. Of course, there are still shipwrecks today, although the last sinking on the Great Lakes was on November 10, 1975, when the SS Edmond Fitzgerald went down in a horrible November gale. With more recent safety regulations, the Great Lakes have been able to stave off shipwrecks in the last 45 years.

Still, it is not the number of wrecks, or even the lives lost, that has me considering a loss that is even greater…and least from the viewpoint of genealogy. As I was listening to the book, I heard that in several situations, they could not get an exact count of the lost, even if they technically knew how many were on board. The ships manifests had gone down with the ship. My mind raced. If there were people on those ships who had  immigrated here, and their names were not recorded somewhere, they could virtually disappear and along with them, their line in the family tree they came from. I know that the many genealogy fanatics, like me, would just cringe at the thought of one of our ancestors simply vanishing. There are so many ways for a family line to get muddied. Name changes, marriages, undocumented deaths, as well as those who just left without telling anyone, are all among the lost ones, but I hadn’t considered those who meant to stay in touch, but who were never heard from, and their family back in Europe or wherever they came from, had no idea what happened. All they knew was that they were lost forever.

immigrated here, and their names were not recorded somewhere, they could virtually disappear and along with them, their line in the family tree they came from. I know that the many genealogy fanatics, like me, would just cringe at the thought of one of our ancestors simply vanishing. There are so many ways for a family line to get muddied. Name changes, marriages, undocumented deaths, as well as those who just left without telling anyone, are all among the lost ones, but I hadn’t considered those who meant to stay in touch, but who were never heard from, and their family back in Europe or wherever they came from, had no idea what happened. All they knew was that they were lost forever.

When my daughter, Amy Royce and her family moved to Washington state a few years ago, I began to take an interest in the Pacific Northwest. I think mostly it was so that I could tell her about things to go see. I don’t know how interested a non-tourist is about those things, but I have certainly found that I am.

When my daughter, Amy Royce and her family moved to Washington state a few years ago, I began to take an interest in the Pacific Northwest. I think mostly it was so that I could tell her about things to go see. I don’t know how interested a non-tourist is about those things, but I have certainly found that I am.

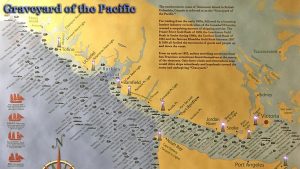

Like anyplace where there is shipping, there is likely to be shipwrecks. The Great Lakes, with their horrible weather conditions in the winter months, are littered with them. The waters of the Pacific Northwest have somehow always seemed rather benign to me, but as I learned about an area called The Graveyard of the Pacific, it occurred to me that maybe they are anything but benign. The Graveyard of the Pacific is a somewhat loosely defined stretch of the Pacific Northwest coast stretching from around Tillamook Bay on the Oregon Coast, running northward past the treacherous Columbia Bar and Juan de Fuca Strait, and up the rocky western coast of Vancouver Island to Cape Scott. Unpredictable weather conditions, fog and coastal characteristics such as shifting sandbars, tidal rips and rocky reefs and shorelines which are common to the area, have claimed more than 2,000 shipwrecks in this area. That makes the area, in my mind anyway, practically cluttered with debris.

In a way, it makes perfect sense, given the fact that many of our nation’s storms enter the continental United States from that area…excluding the tropical hurricanes, of course. With the unpredictable and frequently heavy weather and a rocky coastline, especially along Vancouver Island and its northwestern tip at Cape Scott, have endangered and wrecked thousands of marine vessels since European exploration of the area began in the 18th century. The area has claimed more than 2000 vessels and 700 lives near the Columbia Bar alone, and one book about shipwrecks lists 484 wrecks at the south and west sides of Vancouver Island. Combinations of fog, wind, storm, current and waves have crashed hundreds of ships in the region by the middle of the twentieth century, including famous wrecks in regional history.

The area is home to some famous and dangerous landmarks…Columbia Bar, a giant sandbar at the mouth of the Columbia River; Cape Flattery Reefs and rocks lining the west coast of Vancouver Island; and the Strait of San Juan de Fuca. The shipwreck charts of the area are studded with wreck sites. There have been a number of salvage attempts, but they are often unsuccessful or of limited success, and physical wreckage is usually minimal anyway due to the age of many wrecks. The weather is very unpredictable and the sea conditions harsh. This brings extensive damage to the vessels at the time they were wrecked.

The term, The Graveyard of the Pacific is believed to have originated from the earliest days of the maritime fur trade, not only as increasing numbers of traders’ ships began to be wrecked, but also because of the ongoing

state of incipient warfare in the area between Russia, Spain, Great Britain, and native tribal peoples, making it one of the most dangerous and deadly regions to trade in the Pacific for political as well as climatic reasons. Although major wrecks have declined since the 1920s, several lives are still lost annually. The Graveyard of the Pacific remains a dangerous area, but with modern science, storms aren’t as unpredictable, so watching weather reports can prevent many dangerous situations.

state of incipient warfare in the area between Russia, Spain, Great Britain, and native tribal peoples, making it one of the most dangerous and deadly regions to trade in the Pacific for political as well as climatic reasons. Although major wrecks have declined since the 1920s, several lives are still lost annually. The Graveyard of the Pacific remains a dangerous area, but with modern science, storms aren’t as unpredictable, so watching weather reports can prevent many dangerous situations.

When a lake, or group of lakes, are almost the size of a small sea, with all the storm possibilities that go with a body of water the size of the sea, shipwrecks and other disasters on the water are bound to occur. There is a stretch of land along the Michigan coast, known to many as the Shipwreck Coast or the Graveyard of the Great Lakes. It is an 80 mile stretch between Grand Island and Whitefish Point, and the vicious waters have sunk hundreds of ships. Edmund Fitzgerald, Cyprus, and Vienna are just a few of the vessels lost beneath the waves, where they took their crew to a watery grave…their names forever etched in maritime lore. Their wreckages lie in varying depths of Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes.

When a lake, or group of lakes, are almost the size of a small sea, with all the storm possibilities that go with a body of water the size of the sea, shipwrecks and other disasters on the water are bound to occur. There is a stretch of land along the Michigan coast, known to many as the Shipwreck Coast or the Graveyard of the Great Lakes. It is an 80 mile stretch between Grand Island and Whitefish Point, and the vicious waters have sunk hundreds of ships. Edmund Fitzgerald, Cyprus, and Vienna are just a few of the vessels lost beneath the waves, where they took their crew to a watery grave…their names forever etched in maritime lore. Their wreckages lie in varying depths of Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes.

My husband, Bob and I came up for a visit in 1975, and my Uncle Bill Spencer, the original family historian, told us about the shipwrecks of Lake Superior, and how there were many that could be seen pretty clearly when flying over the lake. I wished we could have taken such a flight, and seen those ships for myself. My thoughts drifted to the time of the wrecks, and how the accident happened and about the people who lost their lives there.

My husband, Bob and I came up for a visit in 1975, and my Uncle Bill Spencer, the original family historian, told us about the shipwrecks of Lake Superior, and how there were many that could be seen pretty clearly when flying over the lake. I wished we could have taken such a flight, and seen those ships for myself. My thoughts drifted to the time of the wrecks, and how the accident happened and about the people who lost their lives there.

Lake Superior was known for its big storms, and when the November gales came it was treacherous, especially along the Shipwreck Coast. “This part of Lake Superior is particularly treacherous thanks to a unique combination of geography and storm patterns,” Bruce Lynn, executive director of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Paradise, Michigan says. “Storms build up over Canada and the Great Plains. Their strong winds blow uninterrupted over 200 miles of open waters, building up enormous waves that drive ships into the coast or break them in half.” Fog, snow squalls, smoke from forest fires, traffic jams on the busy waters and human error add to sailing hazards.

One massive ore carrier, the Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest to sail Lake Superior, nevertheless, it was a gale or a rogue wave that caused its sinking, but what it was is debated to this day. Gordon Lightfoot immortalized the tragedy in his song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” The Fitzgerald’s 200 pound bronze bell was salvaged from the bottom of the lake later on, and and restored. The men were never recovered, because as most people know, Lake Superior never gives up her dead. The ship darted out on November 7, 1975, hoping to make Whitefish Point, but that was not to be. I think that just the questions behind the shipwrecks on Lake Superior makes the thousands of shipwrecks a huge mystery.

One massive ore carrier, the Edmund Fitzgerald was the largest to sail Lake Superior, nevertheless, it was a gale or a rogue wave that caused its sinking, but what it was is debated to this day. Gordon Lightfoot immortalized the tragedy in his song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” The Fitzgerald’s 200 pound bronze bell was salvaged from the bottom of the lake later on, and and restored. The men were never recovered, because as most people know, Lake Superior never gives up her dead. The ship darted out on November 7, 1975, hoping to make Whitefish Point, but that was not to be. I think that just the questions behind the shipwrecks on Lake Superior makes the thousands of shipwrecks a huge mystery.

In September of 1975, my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I made a trip to Superior, Wisconsin to visit my Uncle Bill Spencer and his family. Uncle Bill and I had always been close, and it was a trip I thoroughly enjoyed. Part of the trip included driving around the shores of Lake Superior, while Uncle Bill gave us some history of the area, including the many shipwrecks that had occurred in the lake. Lake Superior is the largest fresh water lake in the world, and in reality it is more a sea than a lake. The lake experiences treacherous storms, especially in November when the Winter gales sweep over the it. With a huge shipping industry operating on the lake every year, accidents are bound to happen periodically, especially if a ship is caught out on the lake too late in the season. Listening to Uncle Bill tell us about the ghosts of Lake Superior, as the wrecks were called, and how you could see them beneath the water if you flew over the lake, peeked my curiosity about when and where the ships had lost their battles with the lake.

In September of 1975, my husband, Bob Schulenberg and I made a trip to Superior, Wisconsin to visit my Uncle Bill Spencer and his family. Uncle Bill and I had always been close, and it was a trip I thoroughly enjoyed. Part of the trip included driving around the shores of Lake Superior, while Uncle Bill gave us some history of the area, including the many shipwrecks that had occurred in the lake. Lake Superior is the largest fresh water lake in the world, and in reality it is more a sea than a lake. The lake experiences treacherous storms, especially in November when the Winter gales sweep over the it. With a huge shipping industry operating on the lake every year, accidents are bound to happen periodically, especially if a ship is caught out on the lake too late in the season. Listening to Uncle Bill tell us about the ghosts of Lake Superior, as the wrecks were called, and how you could see them beneath the water if you flew over the lake, peeked my curiosity about when and where the ships had lost their battles with the lake.

Just a month later, on November 10, 1975, while driving around the lake on his way back from a gun show, Uncle Bill experienced the gales of November from the lake shore, not knowing at the time that the SS Edmond Fitzgerald was fighting for its life, in a losing battle on the lake. The ship had made a run for it from Superior, Wisconsin, but found itself in serious trouble the next day. This was not going to be a battle the ship or her  crew would survive. The SS Edmund Fitzgerald had once been the largest and fastest ship on the Great Lakes, at 729 feet in length. First launched in 1958, its service would be cut short that fateful day in 1975.

crew would survive. The SS Edmund Fitzgerald had once been the largest and fastest ship on the Great Lakes, at 729 feet in length. First launched in 1958, its service would be cut short that fateful day in 1975.

The ship left Burlington Northern Railroad Dock, Number 1 at Superior, Wisconsin on November 9th, carrying 26,116 tons of iron ore pellets. The next day it was hit with a storm packing 60 mile per hour winds and waves in excess of 15 feet. Captain Ernest McSorley steered north, trying to make it to safety in Whitefish Bay, but then the radar failed and the storm took out the power at Whitefish Bay taking with it Whitefish Point’s radio beacon. McSorley was traveling blind. The huge wave swept over the ship, and it began taking on water. A ship taking on water is never a good thing, but when you add to that 26,116 tons of iron ore pellets, that ship is in trouble. Another ship, the Anderson stayed in radio contact with the Fitzgerald, trying to help it reach the bay, but to no avail. Just after 7pm on November 10th, 17 miles from Whitefish Bay, the Fitzgerald made its last radio transmission. The ship, sunk lower and lower from the added weight of the water until its bow pitched down into the lake and the vessel was unable to recover. The ship broke in two, either from waves and water or on its way to the bottom, taking with it cargo and crew. None of the 29 men aboard survived.

It’s not hard to imagine why the shipwrecks are called the Ghosts of Lake Superior, because many, if not all of

them took with them the men and women who had been their crew. Most of those lost souls are still there in a watery grave, because it is too difficult to recover the bodies. The Edmund Fitzgerald now lies under 530 feet of water, broken in two sections. It is just one of at least 52 ships that litter the bottom of the lake. On July 4, 1995, the ship’s bell was recovered from the wreck, and a replica, engraved with the names of the crew members who perished in this tragedy, was left in its place. The original bell is on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point in Michigan.

them took with them the men and women who had been their crew. Most of those lost souls are still there in a watery grave, because it is too difficult to recover the bodies. The Edmund Fitzgerald now lies under 530 feet of water, broken in two sections. It is just one of at least 52 ships that litter the bottom of the lake. On July 4, 1995, the ship’s bell was recovered from the wreck, and a replica, engraved with the names of the crew members who perished in this tragedy, was left in its place. The original bell is on display at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point in Michigan.

When we think of hurricanes, we think of the ocean, but on November 7, 1913, there was a storm over the Great Lakes that would go down in United States history as the largest inland maritime disaster, in terms of number of ships lost. The storm was nicknamed the White Hurricane. The storm system brought blizzard conditions to areas all around the Great Lakes, with hurricane force winds. The nature of the storm was unique and powerful, and caught even the most seasoned captain by surprise. Two low pressure centers merged and rapidly intensified over the Lake Huron, with periods of storm-force winds occurring over a four day period. Surrounding ports signaled it was a level-four storm, but for some vessels, it was already too late. Major ship wrecks took place on all the Great Lakes except for Lake Ontario. Vessels at that time could withstand 90 mile per hour winds and 35 foot waves, but it was the whiteout conditions and accumulation of ice on the ships that turned an already dangerous situation into a deadly one. Ship captains were unable to maintain navigation, resulting in 12 shipwrecks, 19 ships stranded, and an estimated 250 lives lost. On land, 24 inches of snow shut down traffic and communication, causing millions of dollars in damage.

When we think of hurricanes, we think of the ocean, but on November 7, 1913, there was a storm over the Great Lakes that would go down in United States history as the largest inland maritime disaster, in terms of number of ships lost. The storm was nicknamed the White Hurricane. The storm system brought blizzard conditions to areas all around the Great Lakes, with hurricane force winds. The nature of the storm was unique and powerful, and caught even the most seasoned captain by surprise. Two low pressure centers merged and rapidly intensified over the Lake Huron, with periods of storm-force winds occurring over a four day period. Surrounding ports signaled it was a level-four storm, but for some vessels, it was already too late. Major ship wrecks took place on all the Great Lakes except for Lake Ontario. Vessels at that time could withstand 90 mile per hour winds and 35 foot waves, but it was the whiteout conditions and accumulation of ice on the ships that turned an already dangerous situation into a deadly one. Ship captains were unable to maintain navigation, resulting in 12 shipwrecks, 19 ships stranded, and an estimated 250 lives lost. On land, 24 inches of snow shut down traffic and communication, causing millions of dollars in damage.

The storm took place before the time when weather forecasters had the luxury of computer models, the detailed surface and upper air observations, weather satellites, or radar needed to make the most accurate predictions. Had weather forecasters then been able to access modern forecasting equipment, they may have been able to determine the likely development of this type of storm system in advance, as they did with Superstorm Sandy in 2012. As part of the forecast for Sandy forecasters were able to predict storm force winds over the lower Great Lakes five days in advance. The technology and forecast models available to forecasters today led to a more accurate forecast which saved mariners, recreational boaters, and businesses millions, as they were able to make preparations in advance of Sandy’s storm force winds and near 20 foot waves.

One hundred years later, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, in the Great Lakes is commemorating the Storm of 1913, not only for the pivotal role it played in the history of the Great Lakes, but also for its enduring influence. Modern systems of shipping communication, weather prediction, and storm preparedness have all been fundamentally shaped by the events of November 1913. It’s strange to think that one storm could make such a lasting impact on so many systems, but then it is the need for something better that spurs great inventive minds to invent a solution to a serious problem.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration plays a major role in protecting maritime relics of the past. Included are many of the ships lost in 1913. They have remained preserved deep below the surface of the Great Lakes. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary is a 48-square-mile area of protected territory with one of America’s best preserved and nationally significant collections of shipwrecks. Located in northwestern Lake Huron, Thunder Bay is adjacent to one of the most treacherous stretches of water within the Great Lakes system. Unpredictable weather, murky fog banks, sudden gales, and rocky shoals earned the area the name “Shipwreck Alley.” To date, more than 50 shipwrecks have been discovered within the sanctuary including the Isaac M. Scott, a 504 foot steel freighter lost in the storm of 1913.

This storm holds an interest for me, because at that time in history, my grandparents, Allen and Anna Spencer were living in the Great Lakes area. My grandfather was not part of the crew of any ship, and so any effect to them would have come in the form of very deep snow. My Aunt Laura would have been just 16 months old at  the time. I’m sure that the thought of being stranded in her home, was not a pleasant one for my grandmother, considering Aunt Laura’s very young age, but they survived the White Hurricane, as did most other people, at least those on land anyway. It still seems incredible to me that a storm of that magnitude could have brewed in an inland setting, but then anyone who knows the Great Lakes will tell you that they are so big that they might just as well be considered a sea. The November Gales have long been known as killers, especially over Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes. I’m glad that modern weather forecasting equipment had at least lessened the possibility of ships and lives being lost in the Great Lakes, as well as the oceans.

the time. I’m sure that the thought of being stranded in her home, was not a pleasant one for my grandmother, considering Aunt Laura’s very young age, but they survived the White Hurricane, as did most other people, at least those on land anyway. It still seems incredible to me that a storm of that magnitude could have brewed in an inland setting, but then anyone who knows the Great Lakes will tell you that they are so big that they might just as well be considered a sea. The November Gales have long been known as killers, especially over Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes. I’m glad that modern weather forecasting equipment had at least lessened the possibility of ships and lives being lost in the Great Lakes, as well as the oceans.

The Great Lakes are a beautiful series of lakes in the northern United States that for all intents and purposes might as well be the ocean. They are wonderful places for all kinds of recreation, but they are also working lakes, because the Great Lakes handles shipping from all over the world. That said, the summers can be very busy on the Great Lakes, but the winters are a very different thing. Most of the Great Lakes ice over in the winter, or at least enough to make travel on them pretty much impossible. Since the winters are long in the north, the shipping companies try to get every bit of use out of the lakes that they can, and that can bring hazardous and even tragic results.

The Great Lakes are a beautiful series of lakes in the northern United States that for all intents and purposes might as well be the ocean. They are wonderful places for all kinds of recreation, but they are also working lakes, because the Great Lakes handles shipping from all over the world. That said, the summers can be very busy on the Great Lakes, but the winters are a very different thing. Most of the Great Lakes ice over in the winter, or at least enough to make travel on them pretty much impossible. Since the winters are long in the north, the shipping companies try to get every bit of use out of the lakes that they can, and that can bring hazardous and even tragic results.

November is known for screaming into the area, and with it come the Gales. I suppose that to most people, the thought of a dangerous storm of a lake seems a little odd. Yes, if it were a small boat, just about any storm could make for a dangerous situation on the lake, but when you are a big ocean going vessel or ore boat, you wouldn’t think a storm on the lake would be a big deal. You would find that you are wrong on that one though. Over the years, many lives and many ships have been lost on the Great Lakes when the ship was out on the water just a little too late in the season.

Sometimes, it would be a captain who took a chance on the weather, and got himself into trouble, but other times, it would be a situation when the November Gales fooled them and showed up early. Of course, those types of accidents were much more common before all the the weather tracking equipment that is available these days. Some of the deadliest storms were 1860 when the Lady Elgin sank, killing over 400, the 1835 Lake Huron “Cyclone” which claimed 254 lives, the 1913 Great Storm which claimed 244 lives, the 1880 Alpena  Storm which killed about 100, the 1940 Armistice Day storm which took 66 lives, the 1916 Black Friday storm which killed 49, the 1958 sinking of the Bradley with 33 lives lost, the 1905 Blow whish killed 32, the 1975 sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald which took 29 lives, the 1966 sinking of the Morrel which left 28 dead, and the 1894 May Gale which killed 27. These are big storms with big loss of life. On our small lakes, if a summer brings a couple of drownings, we cnsider it a bad year. I can’t imagine what it would be like to lose so many lives all at once on a lake, and yet it is a possibility those in the shipping businesses on the Great Lakes live with every year.

Storm which killed about 100, the 1940 Armistice Day storm which took 66 lives, the 1916 Black Friday storm which killed 49, the 1958 sinking of the Bradley with 33 lives lost, the 1905 Blow whish killed 32, the 1975 sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald which took 29 lives, the 1966 sinking of the Morrel which left 28 dead, and the 1894 May Gale which killed 27. These are big storms with big loss of life. On our small lakes, if a summer brings a couple of drownings, we cnsider it a bad year. I can’t imagine what it would be like to lose so many lives all at once on a lake, and yet it is a possibility those in the shipping businesses on the Great Lakes live with every year.

I remember a visit to my birthplace, Superior, Wisconsin, that my family took when I was a little girl. My Uncle Bill and his family lived up there and still do today. Uncle Bill was and is an interesting sort. He has always liked to collect things. I remember that he had a slot machine in his basement, years ago. Of course, no one was allowed to use it that wasn’t family…a guy could get into trouble otherwise. He collected guns and coins, and he is fanatical about the family history, which I suppose is how I got started writing about the good old days. Uncle Bill got me interested in my past, and my daughters, Corrie and Amy got me into blogging. Writing about the past just seemed to be a good fit for me.

I remember a visit to my birthplace, Superior, Wisconsin, that my family took when I was a little girl. My Uncle Bill and his family lived up there and still do today. Uncle Bill was and is an interesting sort. He has always liked to collect things. I remember that he had a slot machine in his basement, years ago. Of course, no one was allowed to use it that wasn’t family…a guy could get into trouble otherwise. He collected guns and coins, and he is fanatical about the family history, which I suppose is how I got started writing about the good old days. Uncle Bill got me interested in my past, and my daughters, Corrie and Amy got me into blogging. Writing about the past just seemed to be a good fit for me.

As I said, Uncle Bill liked to do things a little differently. I remember going out to pick blueberries and experiencing the difference you can only get when you eat blueberries that have just been picked. It is hard to describe how amazing that taste is.

Uncle Bill was a history buff too. He has always been interested in the shipwrecks in Lake Superior. He could probably tell you about every one. When Bob and I went up to visit the year after our marriage, he told us about many of those wrecks, and how many were visible from the air. That seems odd to me considering the fact that Lake Superior is the deepest of the Great Lakes.

But, one of the most unusual things that Uncle Bill did was a complete surprise and totally delightful to all of us. We had gone for a visit, and he was going to take us out for dinner. When we got to the restraunt, it was not what we expected. It was an ice cream shop. We looked at him in amazement, and he announced that we were having an Ice Cream Supper. So, we went in and Uncle Bill said to order whatever we wanted. We had a wonderful time and supper was delicious. Uncle Bill insisted on everyone eating their fill of ice cream. So, when we were all full, Uncle Bill said, “Now…what do you want for dessert!!”