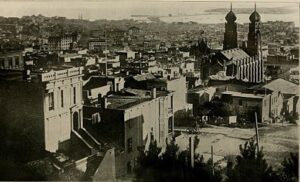

san francisco

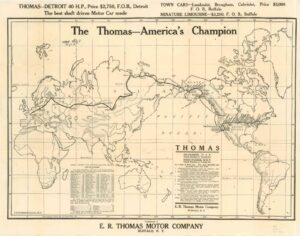

A car race is most often run on a track, with lots of fans cheering everyone on, but in 1908, there was a very strange car race that actually used a track that took the drivers around the world!! How…you might ask?? Well, the car race started in New York City. From there the route took the racers to San Francisco. Normally, San Francisco would be the end of the trail…or the route. You would have reached the Pacific Ocean, and as we all know, cars can’t drive on the ocean…especially cars manufactured in 1908. So, the racers turned to the north and headed for Valdez, Alaska. They would arrive in Valdez in the height of winter…at a time when the Bering Strait was frozen over…theoretically. At that point there was supposed to be an ice bridge across the Bering Strait, making it possible for the cars to drive right over it and into Russia. Once across, the racers would continue on from Russia to Europe and the finish line awaiting them in Paris. It’s amazing to me to think about cars being driven around the world, but of course the Bering Strait in the Winter, supposedly changed everything. In 1908, cars were relatively new, so road infrastructure was limited to only metropolitan areas, and even then, a lot of it was cobbled stone. So, I suppose cross country car travel on dirt trails was not that uncommon.

A car race is most often run on a track, with lots of fans cheering everyone on, but in 1908, there was a very strange car race that actually used a track that took the drivers around the world!! How…you might ask?? Well, the car race started in New York City. From there the route took the racers to San Francisco. Normally, San Francisco would be the end of the trail…or the route. You would have reached the Pacific Ocean, and as we all know, cars can’t drive on the ocean…especially cars manufactured in 1908. So, the racers turned to the north and headed for Valdez, Alaska. They would arrive in Valdez in the height of winter…at a time when the Bering Strait was frozen over…theoretically. At that point there was supposed to be an ice bridge across the Bering Strait, making it possible for the cars to drive right over it and into Russia. Once across, the racers would continue on from Russia to Europe and the finish line awaiting them in Paris. It’s amazing to me to think about cars being driven around the world, but of course the Bering Strait in the Winter, supposedly changed everything. In 1908, cars were relatively new, so road infrastructure was limited to only metropolitan areas, and even then, a lot of it was cobbled stone. So, I suppose cross country car travel on dirt trails was not that uncommon.

The Great Race of 1908 began on February 3rd of that year and immediately ran into challenges. Just to list a few…cars breaking down multiple times, lack of usable roads, car-hating people giving wrong directions, and, oh yeah, SNOW!!! Nevertheless, the teams persevered, and the first team reached San Francisco in 41 days. The came the obstacle of the fact that the proposed route from San Francisco to Alaska did not exist. I guess that they didn’t think it would be feasible to create the route, so the race organizers allowed teams to ship their cars to Valdez, Alaska, then continue on the Ice Bridge. Some might have called that a bit of a cheat, but I guess if all the racers id it, it wasn’t really cheating. Once in Valdez, the teams found out that there is, in fact, no ice bridge across the Bering Strait anymore, because it melted about 20,000 YEARS AGO. Oops…small oversight. So, the racers were allowed to ship their cars across the Pacific to Japan, then Russia, to carry on. Ok, if you’re like me, at this point, you are starting to see that this race had a lot of flaws in the planning. And honestly, while I knew there was no ice bridge on the Bering Strait today, I was unaware that it melted that long ago…meaning there was not an ice bridge since the “Ice Age!!”

So, was this really a car race around the world or a whole lot of non-sense. To be sure, the six teams did end up in Paris after the race, and they drove all of the route that could be driven, but the reality is that much of the race was simply cars being transported by ships across the ocean. Nevertheless, the “official” race was documented as just that…a car race that went around the world. The cars had to fight mud, snow, and mechanical problems. It was “officially” won by The Thomas Flyer, built by the Thomas Motor Company, was a 1907 Model 35 with a 4-cylinder, 60-horsepower engine capable of reaching 60 mph. It was fully loaded with two shovels, two picks, two lanterns, eight searchlights, two extra gas tanks (with a capacity of ten gallons), five hundred feet of rope, a rifle and revolvers. It was also equipped with an attachable top…much like those used on covered wagons…that could wrap the entire car and offer an enclosed place to sleep. On July 30, after 169 days of travel, the Thomas car entered Paris. Even in Paris, they almost didn’t finish, because a police

officer stopped the vehicle, saying it had no working headlight, and couldn’t proceed. A passing bicyclist witnessed the scene and offered to load his bike into the car. Since the bicycle had a working headlight, the officer allowed them to pass. The Thomas Flyer finally finished at 6:00pm. The race was the only “official” car race around the world.

officer stopped the vehicle, saying it had no working headlight, and couldn’t proceed. A passing bicyclist witnessed the scene and offered to load his bike into the car. Since the bicycle had a working headlight, the officer allowed them to pass. The Thomas Flyer finally finished at 6:00pm. The race was the only “official” car race around the world.

On April 18, 1906, many of the people in the San Francisco, California area were sound asleep in their beds. It was, after all, 5:13am. Suddenly, the people were jolted awake by an earthquake, which was estimated to be close to 8.0 on the Richter scale. When the quake struck San Francisco, California, it toppled numerous buildings. The cause of the quake was a slip of the San Andreas Fault over a segment about 275 miles long. The resulting shock waves could be felt from southern Oregon down to Los Angeles.

On April 18, 1906, many of the people in the San Francisco, California area were sound asleep in their beds. It was, after all, 5:13am. Suddenly, the people were jolted awake by an earthquake, which was estimated to be close to 8.0 on the Richter scale. When the quake struck San Francisco, California, it toppled numerous buildings. The cause of the quake was a slip of the San Andreas Fault over a segment about 275 miles long. The resulting shock waves could be felt from southern Oregon down to Los Angeles.

At that time, San Francisco’s had a variety of brick buildings and wooden Victorian structures that were not really earthquake reinforced. Nobody knew about making buildings strong enough to resist destruction from an earthquake. It was one of the things we would learn from the results of a disaster. It seems that with each disaster, we learn how to prevent the loss of so many buildings and lives. The old buildings were devastated. Along with the collapsed buildings, came devastating fires, and because many of the water mains had broken, firefighters were prevented from stopping  the fires. Firestorms soon developed citywide. US Army troops from Fort Mason reported to the Hall of Justice around 7am, and San Francisco Mayor E.E. Schmitz set a dusk-to-dawn curfew and authorized soldiers to shoot to kill anyone found looting. Disasters like these always seem to bring out the worst in people, even those who might not have done such things under normal circumstances.

the fires. Firestorms soon developed citywide. US Army troops from Fort Mason reported to the Hall of Justice around 7am, and San Francisco Mayor E.E. Schmitz set a dusk-to-dawn curfew and authorized soldiers to shoot to kill anyone found looting. Disasters like these always seem to bring out the worst in people, even those who might not have done such things under normal circumstances.

As significant aftershocks continued, firefighters and US troops fought desperately to control the ongoing fires. Sadly, that sometimes meant dynamiting whole city blocks to create firewalls. Many people were trapped where they were, because the fires prevented their escape, even though they were not stuck in a collapsed building. Finally, on April 20th, several thousands of refugees were evacuated from the foot of Van Ness Avenue. The army would eventually house 20,000 refugees in more than 20 military-style tent camps across the city. The people had no idea how long they might have to be there.

Most of the fires were extinguished by April 23rd, and the authorities started the task of rebuilding the devastated city. In all, approximately 3,000 people lost their lives as a result of the Great San Francisco Earthquake and the devastating fires it inflicted upon the city. Almost 30,000 buildings were destroyed, including most of the city’s homes and nearly all the central business district. The rebuilding would take a long time, and the new structures were reinforced to be able to better withstand the shaking of the San Andreas fault. This quake may not have been the “Big One” that is predicted, but at an estimated 7.9 or 8.0, it was right up there.

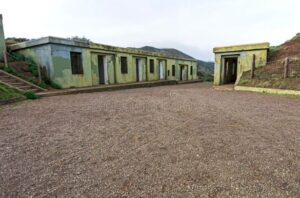

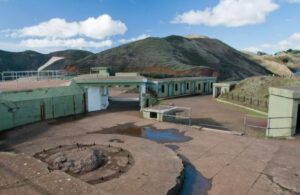

Battery Spencer was a reinforced concrete Endicott Period 12-inch gun battery, which was located on Fort Baker, Lime Point, Marin County, California. The structure still exists today and is a favorite tourist attraction. The battery was named on Feb 14, 1902, after Major General Joseph Spencer, who was a Revolutionary War hero. Spencer died on January 13, 1789. Construction on the battery began in 1893, and it was completed in 1897. Following its completion, it was transferred to the Coast Artillery for use on September 24, 1897, at a total cost of $110,352.70. It was deactivated in 1942 during World War II.

Battery Spencer was a reinforced concrete Endicott Period 12-inch gun battery, which was located on Fort Baker, Lime Point, Marin County, California. The structure still exists today and is a favorite tourist attraction. The battery was named on Feb 14, 1902, after Major General Joseph Spencer, who was a Revolutionary War hero. Spencer died on January 13, 1789. Construction on the battery began in 1893, and it was completed in 1897. Following its completion, it was transferred to the Coast Artillery for use on September 24, 1897, at a total cost of $110,352.70. It was deactivated in 1942 during World War II.

The battery was originally part of the Harbor Defense of San Francisco. The harbor was likely one of the most vulnerable entrances to San Fransisco, and in the early days of the country, when radar didn’t exist, it was hard to tell if an enemy was sneaking into the harbor, especially a submarine. Battery Spencer was a concrete coastal gun battery with three M1888 12-inch guns mounted on long range Barbette M1892 carriages. It was constructed on top of the five front emplacements of Battery Ridge. Back in the early 1900s, Battery Spencer was one of the main protection points for the San Francisco Bay. It featured multiple lookout points that were operated by the military and a few buildings for housing the generators and shells. It was used on and off until World War II when a lot of it was scrapped for war efforts.

The guns were mounted on 3 emplacements. Emplacements #1 and #2 were separated by a magazine with two shell rooms, a powder room, and a shell hoist room. Emplacement #3 had its own shell room, powder room, and hoist room. Spencer Battery was a two-story battery with the magazines on the lower level and the gun emplacements on the upper level. The missiles, or more likely cannon balls at first, were originally moved from the magazine level to the loading level with hand powered projectile hoists. In 1908, the hand powered hoists were replaced with electric Taylor-Raymond front delivery hoists. The new hoists were put into service on September 30, 1908. There were no powder hoists at Battery Spencer, meaning that gun powder had to be moved by hand.

Along the access road that runs north of Emplacement #1, was the BC Post and a separate building that had four rooms. The rooms consisted of a CO room, a guard room, an oil room, and a large 12′ by 43′ plotting room. All of these were used to plan any defensive action taken by the soldiers stationed at Battery Spencer. Two other buildings across the road completed the battery. One housed the tools and rammers, the other a latrine building with separate facilities for officers and enlisted. In 1910 the BC post and the plotting room were remodeled and updated. The work was accepted for service on August 5, 1910, at a cost of $1680.68.

When the United States entered World War I, it was decided that the large caliber coastal defense gun tubes should be removed from coastal batteries and sent into service in Europe. First, they were sent to arsenals for modification and mounting on mobile carriages, both wheeled and railroad. Strangely, most of the removed gun tubes never made it to Europe. Many were either remounted at the batteries or remained at the arsenals until needed elsewhere. One gun was removed from Battery Spencer emplacement #3 in 1918 and sent to Battery Chester at Fort Miley. The gun at Battery Spencer was never replaced, and the emplacement was considered abandoned. The carriage remained in place until it was ordered salvaged on January 10, 1927. World War II brought the first large scale scrap drive, and the remaining two guns and carriages were ordered scrapped on November 19, 1942.

These days Battery Spencer is part of the Golden Gate Recreation Area (GGNRA) administered by the National Park Service. It is a favorite historical attraction, even though no period guns or carriages are in place. The site is also one of the very best views of the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco.

Building in a war zone!! Sounds crazy, right!! Nevertheless, in the middle of the Civil War, the United States began to build a railroad from Iowa to San Francisco, California. As with any railroad, the objective was to create a transcontinental railroad to facilitate transportation all across the nation. This was not going to be a quick project. In fact, it took six years to complete the entire length, but it was a great success. Named the Pacific Railroad, which is not the same as the Union Pacific Railroad, it was a railroad based in Missouri. It was a predecessor of both the Missouri Pacific Railroad and Saint Louis-San Francisco Railway, being chartered in 1849 by Missouri to extend from Saint Louis to the western boundary of Missouri and after Missouri was reached, to run on to the Pacific Ocean. Construction was delayed due to a cholera epidemic in 1849. That and other delays put the groundbreaking on hold until July 4, 1851. As the work progressed, the railroad purchased its first steam locomotive from a manufacturer in Taunton, Massachusetts. The locomotive arrived at Saint Louis by river in August 1852, which is a sight I would have loved to see. We

Building in a war zone!! Sounds crazy, right!! Nevertheless, in the middle of the Civil War, the United States began to build a railroad from Iowa to San Francisco, California. As with any railroad, the objective was to create a transcontinental railroad to facilitate transportation all across the nation. This was not going to be a quick project. In fact, it took six years to complete the entire length, but it was a great success. Named the Pacific Railroad, which is not the same as the Union Pacific Railroad, it was a railroad based in Missouri. It was a predecessor of both the Missouri Pacific Railroad and Saint Louis-San Francisco Railway, being chartered in 1849 by Missouri to extend from Saint Louis to the western boundary of Missouri and after Missouri was reached, to run on to the Pacific Ocean. Construction was delayed due to a cholera epidemic in 1849. That and other delays put the groundbreaking on hold until July 4, 1851. As the work progressed, the railroad purchased its first steam locomotive from a manufacturer in Taunton, Massachusetts. The locomotive arrived at Saint Louis by river in August 1852, which is a sight I would have loved to see. We  don’t think much about a locomotive being delivered by ship these days…mostly because we have the railroad for that delivery, but also because if it was going to be delivered by ship, out ships today are much bigger and better equipped to handle a locomotive.

don’t think much about a locomotive being delivered by ship these days…mostly because we have the railroad for that delivery, but also because if it was going to be delivered by ship, out ships today are much bigger and better equipped to handle a locomotive.

Finally finished to the first leg, the inaugural run of the locomotive took place on December 9, 1852, the Pacific Railroad had its inaugural run, traveling from its depot on Fourteenth Street, along the Mill Creek Valley, to Cheltenham in about ten minutes. It was a good run for the first one, and by the following May, it had reached Kirkwood. Several months later tunnels west of Kirkwood were completed, allowing the line to reach Franklin. The Southwest Branch of the Pacific Railroad was authorized in 1852 and split off at Franklin. This section was renamed Pacific, Missouri, in 1859. The remainder of the Southwest Pacific Railroad became the main line of the Saint Louis-San Francisco Railway in 1866.

Due to financial difficulties the Pacific Railroad did not reach Washington…a mere eighteen miles away, until February 1855. Nevertheless, the line reached Jefferson City, the state capital, later that year. By July 1858 the Pacific Railroad reached Tipton was the eastern terminal for the Butterfield Overland Mail, which was an overland mail service that went on into San Francisco. Adding the railroad to the coach service reduced mail

delivery times between Saint Louis and San Francisco from about 35 days to less than 25 days. After construction was interrupted by the Civil War, the Pacific Railroad became the first railroad to serve Kansas City in 1865. In 1872, the Pacific Railroad was reorganized as the Missouri Pacific Railroad by new investors after a railroad debt crisis.

delivery times between Saint Louis and San Francisco from about 35 days to less than 25 days. After construction was interrupted by the Civil War, the Pacific Railroad became the first railroad to serve Kansas City in 1865. In 1872, the Pacific Railroad was reorganized as the Missouri Pacific Railroad by new investors after a railroad debt crisis.

As the Covid-19 Pandemic has spread across our nation, so has the battle for or against the wearing of face masks. Part of the problem has been the conflicting analysis as to the value of the masks between one doctor and another, one politician and another, or even the same doctor at different times during the crisis. Many states, cities, and even establishments have rules about wearing a mask, with varied levels of enforcement. Of course, we were told to “shelter in place” and close any “non-essential” businesses, a catastrophic event for the economy. Everything from schools to bars, and theaters to salons was closed. Cities became virtual ghost towns, and things like Facebook and Twitter, Zoom and Google Classroom, texting and phone calls became vital. People’s sanity began to take a hit, and loneliness became the norm…especially for anyone who lived alone.

As the Covid-19 Pandemic has spread across our nation, so has the battle for or against the wearing of face masks. Part of the problem has been the conflicting analysis as to the value of the masks between one doctor and another, one politician and another, or even the same doctor at different times during the crisis. Many states, cities, and even establishments have rules about wearing a mask, with varied levels of enforcement. Of course, we were told to “shelter in place” and close any “non-essential” businesses, a catastrophic event for the economy. Everything from schools to bars, and theaters to salons was closed. Cities became virtual ghost towns, and things like Facebook and Twitter, Zoom and Google Classroom, texting and phone calls became vital. People’s sanity began to take a hit, and loneliness became the norm…especially for anyone who lived alone.

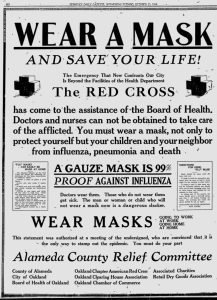

It’s been a grim time, but it isn’t the first time. During the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic, mask wearing started with the first masks being made out of gauze, which was quite porous. Still, in an effort to stop the spread, or as we would say these days, flatten the curve, all the people were now asked to wear masks. In fact, in the Fall of 1918, it became mandatory. With the second surge in December 1918, new restrictions went into place. The January 1919 ordinance had a much larger impact in creating resistance to wearing a mask in public by American citizens. However, it too was short lived, and on February 1, 1919 the city ordinance requiring every citizen of San Francisco going out in public to wear masks was voted down. The mandatory mask laws for COVID-19 are not new. This has already happened twice in American history and if you do feel strongly about not wearing one, it has been protested successfully before in a pandemic caused by a much deadlier virus.

I don’t believe the resistance, with was called the Anti-Mask League of San Francisco fell along party lines, like  much of today’s resistance seems to be, but were rather a diverse bunch of individuals with varying professional backgrounds. Its members included physicians, libertarians, and many others. Many of the same arguments we have today, were in place then, and it is debatable as to whether or not the masks of today are any better than the ones back then…with the possible exception of the medical grad hazard wear, the N-95 mask, and the Head gear. Pretty much everything we’ve tried with Covic-19 was also used in 1918 to try to prevent the spread of the flu…close schools, wear masks, don’t cough or sneeze in someone’s face, avoid large events and hold them outside when possible, and of course, no spitting. There were many ways to get the word out, like in Philadelphia, where streetcar signs warned “Spit Spreads Death.” In New York City, officials enforced no-spitting ordinances and encouraged residents to cough or sneeze into handkerchiefs (a practice that caught on after the pandemic). The city’s health department even advised people not to kiss “except through a handkerchief,” and wire reports spread the message around the country. I don’t know…does any of this sound familiar to you, because it sure does to me. I guess there really is nothing new under the sun. In western states, some cities even called mask ordinances a patriotic duty. In October 1918, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a public service announcement telling readers that “The man or woman or child who will not wear a mask now is a dangerous slacker.” This was in reference to the type of World War I “slacker” who didn’t help the war effort. One sign in California threatened, “Wear a Mask or Go to Jail.” The PSA in the Chronicle appeared on October 22, just over a week before San Francisco had scheduled its mask ordinance to begin on November 1. It was signed by the mayor, the city’s board of health, the American Red Cross and several other departments and organizations, and it was very clear about its message: “Wear a Mask and Save Your Life!”

much of today’s resistance seems to be, but were rather a diverse bunch of individuals with varying professional backgrounds. Its members included physicians, libertarians, and many others. Many of the same arguments we have today, were in place then, and it is debatable as to whether or not the masks of today are any better than the ones back then…with the possible exception of the medical grad hazard wear, the N-95 mask, and the Head gear. Pretty much everything we’ve tried with Covic-19 was also used in 1918 to try to prevent the spread of the flu…close schools, wear masks, don’t cough or sneeze in someone’s face, avoid large events and hold them outside when possible, and of course, no spitting. There were many ways to get the word out, like in Philadelphia, where streetcar signs warned “Spit Spreads Death.” In New York City, officials enforced no-spitting ordinances and encouraged residents to cough or sneeze into handkerchiefs (a practice that caught on after the pandemic). The city’s health department even advised people not to kiss “except through a handkerchief,” and wire reports spread the message around the country. I don’t know…does any of this sound familiar to you, because it sure does to me. I guess there really is nothing new under the sun. In western states, some cities even called mask ordinances a patriotic duty. In October 1918, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a public service announcement telling readers that “The man or woman or child who will not wear a mask now is a dangerous slacker.” This was in reference to the type of World War I “slacker” who didn’t help the war effort. One sign in California threatened, “Wear a Mask or Go to Jail.” The PSA in the Chronicle appeared on October 22, just over a week before San Francisco had scheduled its mask ordinance to begin on November 1. It was signed by the mayor, the city’s board of health, the American Red Cross and several other departments and organizations, and it was very clear about its message: “Wear a Mask and Save Your Life!”

“Red Cross headquarters in San Francisco made 5,000 masks available to the public at 11:00am, October 22. By noon it had none,” wrote the late historian Alfred W Crosby in America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. “By noon the next day Red Cross headquarters had dispensed 40,000 masks. By the twenty-sixth 100,000 had been distributed in the city… In addition, San Franciscans were making thousands for themselves.” Lasting from February 1918 to April 1920, the Spanish Flu Pandemic infected 500 million people…about a third  of the world’s population at the time, in four successive waves. The death toll is typically estimated to have been somewhere between 17 million and 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. With all the safeguards, and the lack of success in “stopping the spread,” I guess it is up to each individual to decide on the effectiveness, or the lack thereof, concerning the safeguards that were put in place. To me, it seems that we have done pretty much the same things today as they did in 1918, so only time will tell us if they were successful, or a waste of time and money. Still, since the Spanish Flue had 4 waves, it doesn’t seem like we successfully stopped anything.

of the world’s population at the time, in four successive waves. The death toll is typically estimated to have been somewhere between 17 million and 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. With all the safeguards, and the lack of success in “stopping the spread,” I guess it is up to each individual to decide on the effectiveness, or the lack thereof, concerning the safeguards that were put in place. To me, it seems that we have done pretty much the same things today as they did in 1918, so only time will tell us if they were successful, or a waste of time and money. Still, since the Spanish Flue had 4 waves, it doesn’t seem like we successfully stopped anything.

Very few people these days haven’t heard of Captain Chesley B. “Sulley” Sullenberger III and co-pilot Jeff Skiles who made their now famous landing on the Hudson River in New York City after a bird strike left them powerless. We all know that everyone “miraculously” survived that crash landing. It was an undeniable miracle, but it was not the first time such a thing had happened. On October 16, 1956, Pan Am Flight 6, a Boeing 377 Stratocruiser on a nighttime flight from Honolulu to San Francisco, developed engine trouble in one and then two of its four engines. Pan Am Flight 6 was about halfway across the Pacific Ocean at the time and the malfunctioning engine propeller sent the airplane into a descent. I can only imagine the thoughts racing through the minds of the pilots, given the fact that they were not going to find a highway or a field on which to land safely. There was only ocean. This was not the first time a plane had to ditch in the ocean, but I doubt that was any comfort to the men who were flying the plane, since the other ditching events had fatalities.

Very few people these days haven’t heard of Captain Chesley B. “Sulley” Sullenberger III and co-pilot Jeff Skiles who made their now famous landing on the Hudson River in New York City after a bird strike left them powerless. We all know that everyone “miraculously” survived that crash landing. It was an undeniable miracle, but it was not the first time such a thing had happened. On October 16, 1956, Pan Am Flight 6, a Boeing 377 Stratocruiser on a nighttime flight from Honolulu to San Francisco, developed engine trouble in one and then two of its four engines. Pan Am Flight 6 was about halfway across the Pacific Ocean at the time and the malfunctioning engine propeller sent the airplane into a descent. I can only imagine the thoughts racing through the minds of the pilots, given the fact that they were not going to find a highway or a field on which to land safely. There was only ocean. This was not the first time a plane had to ditch in the ocean, but I doubt that was any comfort to the men who were flying the plane, since the other ditching events had fatalities.

Pan Am World Airways first started flying in 1927, delivering mail between Florida and Cuba. The carrier was based out of New York City for nearly 30 years, until it went out of business in 1991. The airline left a legacy of firsts. “It was first across the Atlantic, first with flights across the Pacific and the first to offer around-the-world service,” said Kelly Cusack, the curator of the Pan Am Museum Foundation. Most airlines celebrate a lot of their firsts, but there is one first that no airline wants to celebrate, or have on their list of firsts at all…a crash. Nevertheless, on October 16, 1956, a crash was exactly what was going to happen. This crash took place 53 years before “Sulley’s” famous water landing into the Hudson River. “This is a particularly memorable and a proud part of our legacy because of two words: happy ending,” said Jeff Kriendler, who was Pan Am’s vice president for corporate communications in the 1980s and has written several anthologies about the airline. Airlines have ditched in the ocean before, but this was the first to do so with no fatalities. Like “Sulley’s” famous flight, ditching in the ocean without fatalities…was unheard of. Unlike “Sulley’s” landing, which was caught on camera, a nighttime flight in the middle of the ocean in 1956 was not likely to be caught on camera.

The flight started out smoothly, but then developed engine trouble in one, and then two of its four engines. Pan  Am Flight 6 was about halfway across the Pacific Ocean at the time and the malfunctioning engine propeller sent the airplane into a descent. The decision to land the plane in the sea with 24 passengers and seven crew members aboard was not made until all other options had been considered. Captain Richard Ogg, the pilot, wrote an account of the episode a year later, saying that he had to weigh many factors. Should he jettison fuel and try to land on the water immediately or fly until daylight provided better visibility? One thing was clear, the bad propeller was causing the plane to burn fuel too fast. He would not make it to San Francisco or Honolulu. Apparently, it was no coincidence that the ship was nearby. In the early days of long flights over water, Coast Guard ships were positioned in the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans, offering weather information to flight crews and relaying radio messages, according to Doak Walker, a Coast Guard historian who participated in the rescue of Flight 6. In preparation, the cutters were placed near what was expected to be the point of no return. That is the area where a plane would have burned too much fuel to turn back in case of an emergency.

Am Flight 6 was about halfway across the Pacific Ocean at the time and the malfunctioning engine propeller sent the airplane into a descent. The decision to land the plane in the sea with 24 passengers and seven crew members aboard was not made until all other options had been considered. Captain Richard Ogg, the pilot, wrote an account of the episode a year later, saying that he had to weigh many factors. Should he jettison fuel and try to land on the water immediately or fly until daylight provided better visibility? One thing was clear, the bad propeller was causing the plane to burn fuel too fast. He would not make it to San Francisco or Honolulu. Apparently, it was no coincidence that the ship was nearby. In the early days of long flights over water, Coast Guard ships were positioned in the Pacific and the Atlantic Oceans, offering weather information to flight crews and relaying radio messages, according to Doak Walker, a Coast Guard historian who participated in the rescue of Flight 6. In preparation, the cutters were placed near what was expected to be the point of no return. That is the area where a plane would have burned too much fuel to turn back in case of an emergency.

Ogg opted to fly an eight-mile circuit above the Pontchartrain until morning while planning for the water landing. Remembering that during another Pan Am Stratocruiser ditching, the tail had broken off, Ogg had the passengers in the back of the plane move forward and asked those seated by the engine to move as well. “We will try to stay aloft until daylight,” Ogg radioed to the Pontchartrain. When the passengers learned the flight would circle and not attempt to land in the dark, “it gave them a lot of confidence,” said Frank Garcia, 91, the flight engineer and a guest of honor at the Pan Am event. Passengers were also comforted knowing “someone was out there waiting to give them as much aid as they can,” Garcia said. Standing watch on the cutter just after 8 a.m., Walker, 83, recalled that “the seas were extremely calm and the weather was good and we were hoping there wouldn’t be much of a problem.”

Just as Ogg had expected, the tail broke off as soon as the plane hit the sea. Then the nose of the airliner went under the water. “I felt as if somebody had grabbed the seat of my pants and was pulling,” Garcia said. “I saw the water. I was more frightened if the windows broke, then the water would come in.” From the cockpit,  all Garcia saw was water. “I can’t tell you how many seconds, it was less than a minute, and I saw the water receding,” Garcia said, as the front of plane surfaced. On the Pontchartrain many thought they had just witnessed a disaster, Walker said. “It was so sad,” he said. “We knew nobody could survive that.” Rescue boats sped toward the plane, while other Coast Guardsmen filmed the event. Captured moments included life rafts bobbing by the aircraft’s fuselage, transferring survivors to rescue boats, the sinking plane, and the lifting of twin toddlers, Maureen and Elizabeth Gordon, from a lifeboat into waiting seamen’s arms. And, everyone was saved. It was a miracle at sea.

all Garcia saw was water. “I can’t tell you how many seconds, it was less than a minute, and I saw the water receding,” Garcia said, as the front of plane surfaced. On the Pontchartrain many thought they had just witnessed a disaster, Walker said. “It was so sad,” he said. “We knew nobody could survive that.” Rescue boats sped toward the plane, while other Coast Guardsmen filmed the event. Captured moments included life rafts bobbing by the aircraft’s fuselage, transferring survivors to rescue boats, the sinking plane, and the lifting of twin toddlers, Maureen and Elizabeth Gordon, from a lifeboat into waiting seamen’s arms. And, everyone was saved. It was a miracle at sea.

The massive number of ships that sail and have sailed the oceans are mostly safe, but by pure logic, there would also be a number of them for whom safe passage was not to be. For the steamer Alaska, August 8, 1921 would go down in history as the day when her number was up. Shortly after 9:00 pm, the Alaska was sailing south along the California coast, bound for San Francisco, when it hit Blunts Reef…twice. Blunts Reef is located 40 nautical miles south of Eureka, California.

The massive number of ships that sail and have sailed the oceans are mostly safe, but by pure logic, there would also be a number of them for whom safe passage was not to be. For the steamer Alaska, August 8, 1921 would go down in history as the day when her number was up. Shortly after 9:00 pm, the Alaska was sailing south along the California coast, bound for San Francisco, when it hit Blunts Reef…twice. Blunts Reef is located 40 nautical miles south of Eureka, California.

Immediately, the crew knew they were in trouble. Wireless distress signals were flashed. Five miles away the steamer Anyox of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada picked up the signals…quickly, while disregarding fog and placing themselves in danger of striking the same rocks as the Alaska, put on full speed to the rescue. At 9:30 pm the Anyox received the Alaska‘s final message: “We are sinking by the head.” Before the Anyox could reach the stricken Alaska the ship had sunk, but that was not all that happened to the Alaska.

As the ship sunk, the ship’s boilers exploded…passengers and members of the crew of the steamer Alaska were blown from the decks of the vessel into the ocean. The Anyox, traveling dangerously fast in the foggy night, came upon a lifeboat with survivors from the Alaska. The boat was partially filled with sea water and oily scum. The oil, survivors said, had been thrown over them and into their boat by the explosion of the Alaska‘s boilers, which wrecked the Alaska amidships. The sinking of the Alaska took the lives of 48 of the 214 people on board.

According to the survivors, some of the deaths were caused by the explosion, which threw some passengers and members of the crew into the ocean. Some of those blown into the sea regained the vessel or were saved by clinging to wreckage or finding their way into lifeboats. Others, unfortunately, were either killed or drowned before help came. The Alaska’s sinking came so quickly that all the vessel’s lifeboats could not be deployed. JH Moss and CL Vilin, both of Chicago, said the lifeboat they finally reached had been swept off the decks of the Alaska as the ship settled into the ocean. Other lifeboats, never left their davits and went down with the ship. HS Laughlin of Washington DC, where he worked with the United States Shipping Board, said that a Mr and Mrs Phillips tried for an hour to be taken into a lifeboat after they had been thrown off the Alaska into the water. The survivors all praised the efforts of the officers and crew of the rescue ship Anyox under Captain Snoddy, without whom they would not have been alive.

When the Anyox picked up the first lifeboat and took its passengers aboard Second Officer Andrew Sinclair requested permission from Captain Snoddy to take the Alaska‘s lifeboat and seek survivors in the water who were swimming about and clinging to wreckage. Permission given, three seamen volunteered to accompany  Sinclair. They took the lifeboat and within thirty minutes had rescued thirty persons from the water, rafts, and wreckage, and had put them aboard the Anyox. Captain Harry Hobey of the Alaska, the survivors declared, went down with his ship. Coast Guard vessels Sunday patrolled the waters looking for the wreck. The Coast Guard tugboat, Hanger brought in twelve bodies, all covered with oil. Later fishermen brought five additional bodies to San Francisco. Passengers criticized the Alaska‘s lifeboats. It was said some were not properly manned, had insufficient oars and leaked when put into the water. Nevertheless, those lifeboats had held long enough tp get the complaining passengers to safety. Sometimes, it seems like people forget to be thankful.

Sinclair. They took the lifeboat and within thirty minutes had rescued thirty persons from the water, rafts, and wreckage, and had put them aboard the Anyox. Captain Harry Hobey of the Alaska, the survivors declared, went down with his ship. Coast Guard vessels Sunday patrolled the waters looking for the wreck. The Coast Guard tugboat, Hanger brought in twelve bodies, all covered with oil. Later fishermen brought five additional bodies to San Francisco. Passengers criticized the Alaska‘s lifeboats. It was said some were not properly manned, had insufficient oars and leaked when put into the water. Nevertheless, those lifeboats had held long enough tp get the complaining passengers to safety. Sometimes, it seems like people forget to be thankful.

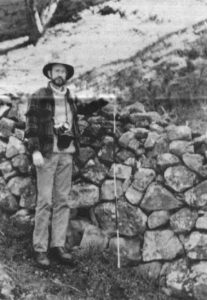

There is a wall that lots o people might have known about, or maybe few people know about, but while I’m sure I’ve seen parts of it in movies, I didn’t really know about it. The series of walls, known as the East Bay Walls or the Berkeley Mystery Walls. Of course that doesn’t really apply to one area, because the reality is that there are many of the crude walls throughout the hills surrounding the San Francisco Bay area. In some place the walls are as much as 3 feet tall, and 3 feet wide. The walls are very old and they were built without mortar. The walls run in sections, and they can be a few feet to over a mile long. Even more odd, is the fact that the rocks are a variety of sizes ranging from basketball-sized rocks, to large sandstone boulders weighing a ton or more. Parts of the walls seem to be just piles of rocks, but in other places it appears the walls were carefully constructed. No one knows the exact age of the walls, but they have an old appearance. Many of the formations have sunk far into the earth, and are often completely overgrown with different plants. The walls are not continuous, so they are not fences. They are not tall enough to have been used as defensive walls. The East Bay Regional Park District simply calls them “rock walls” and insists that they are not mysterious. Livestock, such as cattle, have grazed in the east and south Bay Area hills since the arrival of European

There is a wall that lots o people might have known about, or maybe few people know about, but while I’m sure I’ve seen parts of it in movies, I didn’t really know about it. The series of walls, known as the East Bay Walls or the Berkeley Mystery Walls. Of course that doesn’t really apply to one area, because the reality is that there are many of the crude walls throughout the hills surrounding the San Francisco Bay area. In some place the walls are as much as 3 feet tall, and 3 feet wide. The walls are very old and they were built without mortar. The walls run in sections, and they can be a few feet to over a mile long. Even more odd, is the fact that the rocks are a variety of sizes ranging from basketball-sized rocks, to large sandstone boulders weighing a ton or more. Parts of the walls seem to be just piles of rocks, but in other places it appears the walls were carefully constructed. No one knows the exact age of the walls, but they have an old appearance. Many of the formations have sunk far into the earth, and are often completely overgrown with different plants. The walls are not continuous, so they are not fences. They are not tall enough to have been used as defensive walls. The East Bay Regional Park District simply calls them “rock walls” and insists that they are not mysterious. Livestock, such as cattle, have grazed in the east and south Bay Area hills since the arrival of European  settlers. Clearing land of scattered rocks would have eased the ability to move livestock. Placing the rocks into walls would have helped to guide the movement of the animals or to help corral them. That makes sense, but some of those rocks were very heavy. So how did they do that.

settlers. Clearing land of scattered rocks would have eased the ability to move livestock. Placing the rocks into walls would have helped to guide the movement of the animals or to help corral them. That makes sense, but some of those rocks were very heavy. So how did they do that.

There is no written documentation to identify when they were built, by whom, or why. So, some people consider them mysterious. It has been suggested that the Ohlone Indians might have been the builders, but in reality, they were hunter-gatherers, and didn’t build permanent structures. Some specialists have mentioned that the walls look similar to structures found in rural Massachusetts, Vermont, and Maine, but they are different in that those walls were built around farms by the early setters, and these don’t have the same kinds of layouts. In 1904, UC-Berkeley Professor John Fryer suggested that the walls were made by Mongolian Chinese who traveled to California before the Europeans. Unfortunately, there is little evidence for this or for pre-Columbian Chinese influence in America. Forensic geologist Scott Wolter has theorized that the wall is only two to three hundred years old, suggested by the thick weathering rind on the limestone rock he was authorized to sample. Recent testing of lichen on the rocks suggests that they were probably built between 1850 and 1880, the early American era in California. Settlers might have built the walls using Chinese, Mexican, or Native American laborers, although specifically who built them has not been determined.

One of the many old stone walls that appear around the San Francisco Bay area is in the foothills of eastern  Santa Clara County. The stone walls are accessible in several area parks, including Ed R. Levin County Park in Santa Clara County and Mission Peak Regional Preserve in Alameda County, as well as many other parks. As of 2016, archaeologist Jeffrey Fentress has been measuring and mapping the walls, hoping to eventually gain protection from development or other destruction. Additional stone walls with unclear origin or purpose occur in other places near the San Francisco Bay, and researchers continue to discover more information about the walls. Whether these walls had a purpose at one time or not, they are certainly strange to those who try to look into them these days.

Santa Clara County. The stone walls are accessible in several area parks, including Ed R. Levin County Park in Santa Clara County and Mission Peak Regional Preserve in Alameda County, as well as many other parks. As of 2016, archaeologist Jeffrey Fentress has been measuring and mapping the walls, hoping to eventually gain protection from development or other destruction. Additional stone walls with unclear origin or purpose occur in other places near the San Francisco Bay, and researchers continue to discover more information about the walls. Whether these walls had a purpose at one time or not, they are certainly strange to those who try to look into them these days.

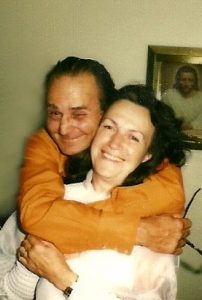

My Aunt Ruth Wolfe was raised on a farm, around horses, and she loved them, as well as most other animals. She really thrived on the country life. She worked hard, alongside her mom and siblings, especially during World War II, when her brother, my dad, Allen Spencer was serving in the Army Air Forces. She helped at the farm and also as a welder at the shipyards…one of the women known as riveters. Later in her life, when she was married, she and my Uncle Jim Wolfe lived in the country outside Casper, Wyoming. They gardened, canned, and raised farm animals. Aunt Ruth was one tough lady. She could do just about anything she set her mind to. From that hard work of farming, to canning, to haying, to playing any instrument, to painting, my Aunt Ruth was simply a multi-talented woman.

My Aunt Ruth Wolfe was raised on a farm, around horses, and she loved them, as well as most other animals. She really thrived on the country life. She worked hard, alongside her mom and siblings, especially during World War II, when her brother, my dad, Allen Spencer was serving in the Army Air Forces. She helped at the farm and also as a welder at the shipyards…one of the women known as riveters. Later in her life, when she was married, she and my Uncle Jim Wolfe lived in the country outside Casper, Wyoming. They gardened, canned, and raised farm animals. Aunt Ruth was one tough lady. She could do just about anything she set her mind to. From that hard work of farming, to canning, to haying, to playing any instrument, to painting, my Aunt Ruth was simply a multi-talented woman.

I think one of the strangest moves Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim made was the one to Vallejo, California. I couldn’t quite figure out why a person who loved the country so much, would move to a city. Vallejo is a suburb of San Francisco, California, and very different from Casper, Wyoming or Holyoke, Minnesota. I suppose they decided that they wanted a change of pace, and I can understand that, because my family and I lived in the country for a number of years before we moved into town in Casper. For us, the city life was more…us, at least the small city life. I don’t think I would want to live in a big city like New York or San Francisco. Still, I can understand why my aunt and uncle might be drawn to the big city life, and the warmer California weather.

After a time in California, the quiet country life again drew them from the big city to the mountains of Washington state. I can’t say that the move to the mountains surprised me much, because it seems like country life was like the blood that ran through my aunt and uncle’s veins. It was a part of who they were, as

much as their DNA was who they were. Once they settled in eastern Washington, they never moved again. They bought the top of a mountain, and built three cabins there…one for them, one for their daughter, Shirley and her husband, Shorty Cameron; and one for their son Terry and his family. For Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim, this would be their forever home. Having been on their mountain top, I can say that I understand why they thought it was so beautiful, but in the years since I moved back to town, I know that I would not want to live permanently in the country, or on a mountain top again. Nevertheless, that was their favorite place to be. Today would have been my Aunt Ruth’s 92nd birthday. It’s hard to believe she has been gone 26 years now. Happy birthday in Heaven Aunt Ruth. We love and miss you so very much, and can’t wait to see you again.

much as their DNA was who they were. Once they settled in eastern Washington, they never moved again. They bought the top of a mountain, and built three cabins there…one for them, one for their daughter, Shirley and her husband, Shorty Cameron; and one for their son Terry and his family. For Aunt Ruth and Uncle Jim, this would be their forever home. Having been on their mountain top, I can say that I understand why they thought it was so beautiful, but in the years since I moved back to town, I know that I would not want to live permanently in the country, or on a mountain top again. Nevertheless, that was their favorite place to be. Today would have been my Aunt Ruth’s 92nd birthday. It’s hard to believe she has been gone 26 years now. Happy birthday in Heaven Aunt Ruth. We love and miss you so very much, and can’t wait to see you again.

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

Most people would agree that the prospect of taking a nation into war is a scary one at best…especially for its citizens. In 1916, the world was in the middle of World War I. Isolationism had been the order of the day, as the United States tried to stay out of this war, but by the summer of 1916, with the Great War raging in Europe, and with the United States and other neutral ships threatened by German submarine aggression, it had become clear to many in the United States that their country could no longer stand on the sidelines. With that in mind, some of the leading business figures in San Francisco planned a parade in honor of American military preparedness. The day was dubbed Preparedness Day, and with the isolationist, anti-war, and anti-preparedness feeling that still ran high among a significant population of the city…and the country, not only among such radical organizations as International Workers of the World (the so-called “Wobblies”) but among mainstream labor leaders. These opponents of the Preparedness Day event undoubtedly shared the view voiced publicly by one critic, former U.S. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who claimed that the organizers, San Francisco’s financiers and factory owners, were acting in pure self-interest, as they clearly stood to benefit from an increased production of munitions. At the same time, with the rise of Bolshevism and labor unrest, San Francisco’s business community was justifiably nervous. The Chamber of Commerce organized a Law and Order Committee, despite the diminishing influence and political clout of local labor organizations. Radical labor was a small but vociferous minority which few took seriously. Nevertheless, it became obvious that violence was imminent.

A radical pamphlet of mid-July read in part, “We are going to use a little direct action on the 22nd to show that militarism can’t be forced on us and our children without a violent protest.” It was in this environment that the Preparedness Parade found itself on July 22, 1916. In spite of that, the 3½ hour long procession of some 51,329 marchers, including 52 bands and 2,134 organizations, comprising military, civic, judicial, state and municipal divisions as well as newspaper, telephone, telegraph and streetcar unions, went ahead as planned. At 2:06pm, about a half hour after the parade began, a bomb concealed in a suitcase exploded on the west side of Steuart Street, just south of Market Street, near the Ferry Building. Ten bystanders were killed by the explosion, and 40 more were wounded, in what became the worst terrorist act in San Francisco history. The city and the nation were outraged, and they declared that justice would be served.

Two radical labor leaders, Thomas Mooney and Warren K Billings, were quickly arrested and tried for the  attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.

attack. In the trial that followed, the two men were convicted, despite widespread belief that they had been framed by the prosecution. Mooney was sentenced to death and Billings to life in prison. After evidence surfaced as to the corrupt nature of the prosecution, President Woodrow Wilson called on California Governor William Stephens to look further into the case. Two weeks before Mooney’s scheduled execution, Stephens commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, the same punishment Billings had received. Investigation into the case continued over the next two decades. By 1939, evidence of perjury and false testimony at the trial had so mounted that Governor Culbert Olson pardoned both men, and the true identity of the Preparedness Day bomber, or bombers, remains forever unknown.