rock springs

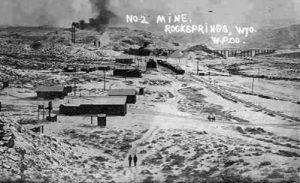

In 1885, coal miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory were trying to unionize, and were trying to strike for better working conditions, but the Union Pacific Railroad company had been besting them in their efforts for a long time. In those days, the companies often had the advantage over the workers. Working conditions suffered as a result of this disadvantage. Unions and companies were constantly at odds, for obvious reasons. I suppose that in any business, there are good and bad people. Sometimes, when people come into power in an organization, corruption follows. The companies of that time didn’t want to do what was necessary to make working in the mines safe, and as most people know, underground mining can be a very dangerous occupation. The chance of cave ins or explosions exists in even the safest mines, as well as having poisonous gasses leaking into the limited air supply, bringing death to the miners.

In 1885, coal miners in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory were trying to unionize, and were trying to strike for better working conditions, but the Union Pacific Railroad company had been besting them in their efforts for a long time. In those days, the companies often had the advantage over the workers. Working conditions suffered as a result of this disadvantage. Unions and companies were constantly at odds, for obvious reasons. I suppose that in any business, there are good and bad people. Sometimes, when people come into power in an organization, corruption follows. The companies of that time didn’t want to do what was necessary to make working in the mines safe, and as most people know, underground mining can be a very dangerous occupation. The chance of cave ins or explosions exists in even the safest mines, as well as having poisonous gasses leaking into the limited air supply, bringing death to the miners.

The situation took a deadly turn on September 2, 1885, when 150 white miners brutally attacked their Chinese coworkers, killing 28 and wounding 11 others, while driving several others out of town. The Chinese weren’t really the problem, except that they were hard workers, and so the company had initially decided to bring them in as strikebreakers. The Chinese workers showed very little interest in the miners’ union, and I’m sure this  made the rest of the miners very angry. The miners became outraged by a company decision to allow the Chinese miners to work in the richest coal mines, and before long, the situation turned into a mob of white miners deciding to strike back by attacking the small area of Rock Springs known as Chinatown.

made the rest of the miners very angry. The miners became outraged by a company decision to allow the Chinese miners to work in the richest coal mines, and before long, the situation turned into a mob of white miners deciding to strike back by attacking the small area of Rock Springs known as Chinatown.

When the Chinese saw the white miners coming, most of them abandoned their homes and business, running for the hills. Those who failed to get out in time were brutally beaten, and 28 of them, beaten to death. One week later, on September 9, United States troops escorted the surviving Chinese back into the town where many of them returned to work. I guess they were either very loyal, desperate for the money, or had no other real choices, because I can’t imagine going back to work in that situation. Eventually the Union Pacific fired 45 of the white miners for their roles in the massacre, but no effective legal action was ever taken against any of the participants…no repercussion for the brutal murder of 28 Chinese men.

I wound never agree with murder, but it was also wrong to use the Chinese in this way. By bringing them in as strikebreakers, the Union Pacific Railroad effectively caused the anti-Chinese sentiment that was shared by  many, and began to come to the West in the mid-nineteenth century, fleeing famine and political upheaval in their own country. The Chinese were many Americans at that time. The Chinese had been victims of prejudice and violence ever since they first widely blamed for all sorts of social ills. They were also singled-out for attack by some national politicians who popularized strident slogans like “The Chinese Must Go” and helped pass an 1882 law that closed the United States to any further Chinese immigration. The Rock Springs massacre was just another symptom in this climate of racial hatred, violent attacks against the Chinese in the West became all too common. But, the Rock Springs massacre was the worst, both for its size and savage brutality.

many, and began to come to the West in the mid-nineteenth century, fleeing famine and political upheaval in their own country. The Chinese were many Americans at that time. The Chinese had been victims of prejudice and violence ever since they first widely blamed for all sorts of social ills. They were also singled-out for attack by some national politicians who popularized strident slogans like “The Chinese Must Go” and helped pass an 1882 law that closed the United States to any further Chinese immigration. The Rock Springs massacre was just another symptom in this climate of racial hatred, violent attacks against the Chinese in the West became all too common. But, the Rock Springs massacre was the worst, both for its size and savage brutality.