protests

The Vietnam War…often thought of as the one America lost, was an unpopular war, as most people know. Protests were everywhere, and some young men ran away to Canada to avoid going to war. Our soldiers were hated, mocked, and protested…especially when they came home from the war. People didn’t line up at airports to welcome them home, they lined up to protest them…calling them “baby killers” and spitting on them. Although such incidents were rare, the stories were often repeated among US soldiers in Vietnam. These stories added to the soldiers’ resentment of the antiwar movement. Rather than being greeted with anger and hostility, however, most Vietnam veterans received very little reaction when they returned home. They mainly noticed that people seemed uncomfortable around them and did not want to talk about their wartime experiences. “Society as a whole was certainly unable and unwilling to receive these men with the support and understanding they needed,” Christian G Appy explains in his book Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam, “The most common experiences of rejection were not explicit acts of hostility but quieter, sometimes more devastating forms of withdrawal, suspicion, and indifference.” There was no tickertape parade to welcome home the heroes…nothing!! The veterans, who were just following orders, doing their duty, were blamed for the decisions of the government to go to war. It doesn’t matter to me whether this war was unnecessary, a lost cause, or a war we should or should not have been in, the soldiers should never have been blames for it. For years after the war, the Vietnam Veterans were shunned, neglected, and ridiculed.

The Vietnam War…often thought of as the one America lost, was an unpopular war, as most people know. Protests were everywhere, and some young men ran away to Canada to avoid going to war. Our soldiers were hated, mocked, and protested…especially when they came home from the war. People didn’t line up at airports to welcome them home, they lined up to protest them…calling them “baby killers” and spitting on them. Although such incidents were rare, the stories were often repeated among US soldiers in Vietnam. These stories added to the soldiers’ resentment of the antiwar movement. Rather than being greeted with anger and hostility, however, most Vietnam veterans received very little reaction when they returned home. They mainly noticed that people seemed uncomfortable around them and did not want to talk about their wartime experiences. “Society as a whole was certainly unable and unwilling to receive these men with the support and understanding they needed,” Christian G Appy explains in his book Working-Class War: American Combat Soldiers and Vietnam, “The most common experiences of rejection were not explicit acts of hostility but quieter, sometimes more devastating forms of withdrawal, suspicion, and indifference.” There was no tickertape parade to welcome home the heroes…nothing!! The veterans, who were just following orders, doing their duty, were blamed for the decisions of the government to go to war. It doesn’t matter to me whether this war was unnecessary, a lost cause, or a war we should or should not have been in, the soldiers should never have been blames for it. For years after the war, the Vietnam Veterans were shunned, neglected, and ridiculed.

By the 1980s, however, many Americans began to change their views of Vietnam veterans. They began to see that even if the war was wrong, most of the men who fought it were just ordinary guys doing their jobs. Many  people started to feel sympathy and even gratitude toward the veterans. Soldiers who had served in Vietnam finally began receiving recognition and were honored by marching in holiday parades across the country. In 1985, Newsweek reported that “America’s Vietnam veterans, once viewed with a mixture of indifference and outright hostility by their countrymen, are now widely regarded as national heroes.” People had finally begun to understand how wrong they had been to blame the veterans for the war. Many people felt remorse for the horrible way this returning heroes were treated. Those who had this change of heart, began to do what they could to make amends. Better late than never, I guess, but in reality, no veteran should ever be treated that way.

people started to feel sympathy and even gratitude toward the veterans. Soldiers who had served in Vietnam finally began receiving recognition and were honored by marching in holiday parades across the country. In 1985, Newsweek reported that “America’s Vietnam veterans, once viewed with a mixture of indifference and outright hostility by their countrymen, are now widely regarded as national heroes.” People had finally begun to understand how wrong they had been to blame the veterans for the war. Many people felt remorse for the horrible way this returning heroes were treated. Those who had this change of heart, began to do what they could to make amends. Better late than never, I guess, but in reality, no veteran should ever be treated that way.

On November 13, 1982, near the end of a weeklong national salute to the American who fought in the Vietnam War, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated in Washington after a march to its site by thousands of veterans of the conflict. The long-awaited memorial was a simple V-shaped black-granite wall inscribed with the names of the 57,939 Americans who died in the conflict, arranged in order of death, not rank, as was common in other memorials. The designer of the memorial was Maya Lin, a Yale University architecture student who entered a nationwide competition to create a design for the monument. Lin was born in Ohio in 1959, the daughter of Chinese immigrants. Many veterans’ groups were opposed to Lin’s winning design, which lacked a standard memorial’s heroic statues and stirring words. However, a remarkable shift in public opinion occurred  in the months after the memorial’s dedication. Veterans and families of the dead walked the black reflective wall, seeking the names of their loved ones killed in the conflict. Once the name was located, visitors often made an etching or left a private offering, from notes and flowers to dog tags and cans of beer. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial soon became one of the most visited memorials in the nation’s capital. A Smithsonian Institution director called it “a community of feelings, almost a sacred precinct,” and a veteran declared that “it’s the parade we never got.” “The Wall” drew together both those who fought and those who marched against the war and served to promote national healing a decade after the division the conflict had caused.

in the months after the memorial’s dedication. Veterans and families of the dead walked the black reflective wall, seeking the names of their loved ones killed in the conflict. Once the name was located, visitors often made an etching or left a private offering, from notes and flowers to dog tags and cans of beer. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial soon became one of the most visited memorials in the nation’s capital. A Smithsonian Institution director called it “a community of feelings, almost a sacred precinct,” and a veteran declared that “it’s the parade we never got.” “The Wall” drew together both those who fought and those who marched against the war and served to promote national healing a decade after the division the conflict had caused.

These days, every military veteran has available to them, a compensation package to thank them for their service. Returning servicemen have access to unemployment compensation, low-interest home and business loans, and…most importantly, funding for education, but this was not always the case. In fact, there was a time when returning veterans had to fight for bonuses they were supposed to receive, which brought about the 1932 Bonus March, in which 20,000 unemployed veterans and their families flocked in protest to Washington. I think most of us would agree that our veterans should not have to fight for the things promised to them for their service, after they have already spent time fighting for their country.

These days, every military veteran has available to them, a compensation package to thank them for their service. Returning servicemen have access to unemployment compensation, low-interest home and business loans, and…most importantly, funding for education, but this was not always the case. In fact, there was a time when returning veterans had to fight for bonuses they were supposed to receive, which brought about the 1932 Bonus March, in which 20,000 unemployed veterans and their families flocked in protest to Washington. I think most of us would agree that our veterans should not have to fight for the things promised to them for their service, after they have already spent time fighting for their country.

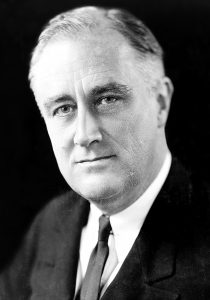

President Franklin D Roosevelt was responsible for the sweeping New Deal reforms, many of which were really not good for this nation or its people, but there was one part of that legislation that has been a good thing for returning veterans…the G.I. Bill. On this day June 22, 1944, President Franklin D Roosevelt signed the G.I. Bill. It was an unprecedented act of legislation designed to compensate returning members of the armed services, known as G.I.s, for their efforts in World War II. The G.I. Bill…officially the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944…was proposed in an effort to avoid a relapse into the Great Depression after the war ended. The American Legion, a veteran’s organization, successfully fought for many of the provisions included in the bill, which gave returning servicemen the compensations they now have. By giving veterans money for tuition, living expenses, books, supplies and  equipment, the G.I. Bill effectively transformed higher education in America. Before the war, college had been an option for only 10-15 percent of young Americans, and university campuses had become known as a haven for the most privileged classes. This was not what America was supposed to be about. By 1947, the contrast was striking. Veterans made up half of the nation’s college enrollment. Three years later, nearly 500,000 Americans graduated from college, compared with 160,000 in 1939. Sure, they had to serve their country, but for many young people, this was not only what they felt was their duty, but it also became a scholarship program.

equipment, the G.I. Bill effectively transformed higher education in America. Before the war, college had been an option for only 10-15 percent of young Americans, and university campuses had become known as a haven for the most privileged classes. This was not what America was supposed to be about. By 1947, the contrast was striking. Veterans made up half of the nation’s college enrollment. Three years later, nearly 500,000 Americans graduated from college, compared with 160,000 in 1939. Sure, they had to serve their country, but for many young people, this was not only what they felt was their duty, but it also became a scholarship program.

As educational institutions opened their doors to this diverse new group of students, overcrowded classrooms and residences prompted widespread improvement and expansion of university facilities and teaching staffs. The bill was not only good for the veterans, but also for the economy, as more teaching jobs were created. An array of new vocational courses were developed across the country, including advanced training in education, agriculture, commerce, mining and fishing…skills that had previously been taught only informally. Some of these classes are responsible for some of the jobs that everyday Americans, even those without college educations have held. Jobs such as mining, and farming, and even fishing became commonplace.

The G.I. Bill became one of the major forces for economic expansion in America that lasted 30 years after World War II. Only 20% of the money set aside for unemployment compensation under the bill was given out. Most veterans found jobs or pursued higher education. Low interest loans enabled millions of American families to move out of cities and buy or build homes outside the city, changing the face of the suburbs. Over 50 years, the impact of the G.I. Bill was enormous, with 20 million veterans and dependents using the education benefits and 14 million home loans guaranteed, for a total federal investment of $67 billion. Among the millions of Americans who have taken advantage of the bill are former Presidents George H.W. Bush and Gerald Ford, former Vice President Al Gore and entertainers Johnny Cash, Ed McMahon, Paul Newman and Clint Eastwood, and closer to home, my brother-in-law, Ron Schulenberg, as well as my nephew, Allen Beach and soon, his wife, Gabby.