pool of peace

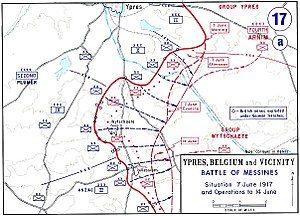

World War I found the British Army with a big problem. The German 4th Army was deeply entrenched at Messines Ridge in northern France, and the British had to remove them…somehow. The British came up with a plan, and for the 18 months prior to June 7, 1917, soldiers had been secretly working to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the German stronghold positions were located. The plan was put into action by the British 2nd Army under the supervision of General Sir Herbert Plumer. The joint explosion of the mines at Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”.

World War I found the British Army with a big problem. The German 4th Army was deeply entrenched at Messines Ridge in northern France, and the British had to remove them…somehow. The British came up with a plan, and for the 18 months prior to June 7, 1917, soldiers had been secretly working to place nearly 1 million pounds of explosives in tunnels under the German positions. The tunnels extended to some 2,000 feet in length, and some were as much as 100 feet below the surface of the ridge, where the German stronghold positions were located. The plan was put into action by the British 2nd Army under the supervision of General Sir Herbert Plumer. The joint explosion of the mines at Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army, remarked to the press, “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”.

On June 7, 1917, they were ready to carry out their secret attack. The explosions created 19 large craters. It would be a crushing victory over the Germans who had no idea of the impending disaster they were about to face. This attack would mark the successful beginning of an Allied offensive designed to break the grinding stalemate on the Western Front in World War I. The time of the attack was set for 3:10am. Precisely on schedule, a series of simultaneous explosions rocked the area. The blast from the detonation of all those landmines was heard as far away as London. A German observer described the explosions, “nineteen gigantic roses with carmine petals, or enormous mushrooms, rose up slowly and majestically out of the ground and

then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

then split into pieces with a mighty roar, sending up multi-colored columns of flame mixed with a mass of earth and splinters high in the sky.” German losses that day included more than 10,000 men who died instantly, along with some 7,000 prisoners…men too stunned and disoriented by the explosions to resist the infantry assault.

Although Messines Ridge battle was, itself was a relatively limited victory, it had a considerable effect on the German morale. The Germans were forced to retreat to the east, a sacrifice that marked the beginning of their gradual, but continuous loss of territory on the Western Front. It also secured the right flank of the British thrust towards the highly contested Ypres region, which was the eventual objective of the planned offensive. Over the next month and a half, British forces continued to push the Germans back toward the high ridge at Passchendaele, which on July 31 saw the launch of the British offensive known as the Battle of Passchendaele. The Battle of Messines marked the high point of mine warfare. On August 10, 1917, the Royal Engineers fired the last British deep mine of the war, at Givenchy-en-Gohelle near Arras.

The explosions left a mine crater 40 feet deep. The attack had done its job. Still, after the war was over, the crater remained, and some wanted to change the “feel” of the place. Nowadays, this mine crater is a serene, contemplative place. I’m sure that many who visit there feel the significance of the location, but also know just  how necessary it was to ensure the freedom of France from the tyranny of the German forces. Named The Pool of Peace, it is a 40 foot deep lake near Messines, Belgium. It fills one of the craters made in 1917 when the British detonated a mine containing 45 tons of explosives. The pool stretches 423 feet across, and remains a place of solace that receives many visitors every year. It seems to me that, while most of those killed in the mine fields on June 7, 1917, were Germans, and therefore, the enemy, they were also people, many of whom didn’t want to be there any more than the Allies did. They were there under orders, and that was all there was to it. For that reason, I believe that place should be, finally, a place of peace.

how necessary it was to ensure the freedom of France from the tyranny of the German forces. Named The Pool of Peace, it is a 40 foot deep lake near Messines, Belgium. It fills one of the craters made in 1917 when the British detonated a mine containing 45 tons of explosives. The pool stretches 423 feet across, and remains a place of solace that receives many visitors every year. It seems to me that, while most of those killed in the mine fields on June 7, 1917, were Germans, and therefore, the enemy, they were also people, many of whom didn’t want to be there any more than the Allies did. They were there under orders, and that was all there was to it. For that reason, I believe that place should be, finally, a place of peace.