pilots

Whether it was World War I or World War II, every flyer knew what a dogfight was. Dogfights were the undisputed, most intense type of aerial combat there was. Basically it was an intense game of chicken…one that no one really wanted to play. The fight for supremacy in the skies over Europe was vital to the war effort. The Axis of Evil nations had to be stopped, and the air war was going to be the way to win the war.

Whether it was World War I or World War II, every flyer knew what a dogfight was. Dogfights were the undisputed, most intense type of aerial combat there was. Basically it was an intense game of chicken…one that no one really wanted to play. The fight for supremacy in the skies over Europe was vital to the war effort. The Axis of Evil nations had to be stopped, and the air war was going to be the way to win the war.

After watching some of the cockpit footage of the dogfights, I don’t know how those pilots did it. In the non-war world, two planes going head to head is not an ideal situation, but that was what the fighter planes of war have to do. As one plane starts to gain dominance over another, the plane being chased often goes into a steep climb, followed by the pursuing plane. The first plane to stall is going to end up being chased, because as he loses power, he drops and then must run first to gain power and then to get away from his attacker. If you thought going head to head with another plane was scary, imagine a deliberate stall…for supremacy!! That just seems insane to me, but that is  the nature of the dogfight. These pilots had to be very brave. There is no way to fly like that, or especially fight like that unless you area very brave pilot…not to mention a skilled pilot. Without that skill, the pilots would not survive long enough to even become an ace.

the nature of the dogfight. These pilots had to be very brave. There is no way to fly like that, or especially fight like that unless you area very brave pilot…not to mention a skilled pilot. Without that skill, the pilots would not survive long enough to even become an ace.

For a fighter pilot to become an ace, he had to shoot down five enemy planes. A gunner could become an ace too, but the majority of aces are fighter pilots. The key to becoming an ace, besides shooting down the enemy, is obviously to stay alive long enough to become an ace. In these dogfights, that was difficult for sure.

Arthur Duperrault dreamed of sailing the high seas. He was a World War II veteran from Green Bay, Wisconsin and he wanted to give his family a sailing adventure. The winter of 1960 was rough, but now the winter of 1961, would be one of sunlight and warmth. Arthur, Jean, Brian, Terry Jo, and Renee, were heading for the Bahamas to soak up some sun. Arthur and his family headed to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where their boat, Bluebelle was waiting for them. It was a sixty foot two-masted sailboat.

Arthur Duperrault dreamed of sailing the high seas. He was a World War II veteran from Green Bay, Wisconsin and he wanted to give his family a sailing adventure. The winter of 1960 was rough, but now the winter of 1961, would be one of sunlight and warmth. Arthur, Jean, Brian, Terry Jo, and Renee, were heading for the Bahamas to soak up some sun. Arthur and his family headed to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where their boat, Bluebelle was waiting for them. It was a sixty foot two-masted sailboat.

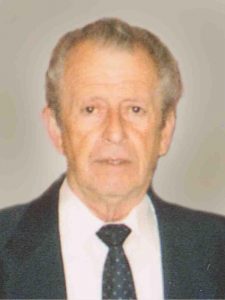

With no real sailing experience, Arthur hired a man named Julian Harvey, who was a decorated Air Force bomber pilot who had served in World War II and the Korean War, to captain for him. Harvey brought along his wife of four months, Mary Dene. On Wednesday, November 8, 1961, Arthur, Julian, and their respective families began their journey. Soon, the occupants of Bluebelle would be in the Bahamas. First, Harvey steered Bluebelle toward Bimini, a miniature island chain. Then headed east, to Sandy Point, a village located on the southwest point of the Great Abaco Island. Here, the vacationers filled their days with snorkeling and picking up shells on the beautiful beaches.

On Sunday, November 12, 1961, Arthur and Julian went to the office of Roderick Pinder, who was Sandy Point’s commissioner, to fill out the forms that they needed to properly leave the Bahamas. Arthur told Roderick. “We’ll be back before Christmas.” Little did Arthur, his wife, or three children know, they would not be coming back for Christmas. Sunday would be Arthur’s last night alive. It would also be last night alive for Jean, Brian, Renee, and Julian Harvey’s wife, Mary Dene. Sunday dinner was cooked by Mary Dene, who made a chicken cacciatore and salad for the two families. At 9:00 pm that night, Terry Jo went to bed. Her room was in a small cabin in the back of the boat. Usually, Renee, her young sister, slept there too, but tonight, she was with her mom, dad, and brother in the cockpit. In the middle of the night, Terry Jo heard her brother scream, “Help, daddy, help!” The screams were followed by running and stamping noises. Terry Jo was terrified. After the running, the stamping, and the screams stopped, there was an eerie silence.

Terry Jo was terrified, but found the courage to leave her cabin. The main cabin, a kitchen and dining room during the day, transformed into a bedroom at night. There she saw her mom and big brother, in a pool of blood…dead. Cautiously, she went to check the other areas of the boat. Near the cockpit, she saw more blood and a knife. She made her way to the front of the boat. As Terry Jo was viewing the horror in front of her, somebody lunged at her. It wasn’t a stranger…it was the captain, Julian Harvey. “Get back down there!” he  screamed. With her heart pounding, Terry Jo went back to her cabin. She crawled into her bunk. Soon, water coming into the cabin told her that Bluebelle was sinking. She was too afraid to move. However, Harvey was moving all over the place. Soon, she saw Harvey in the doorway holding her big brother’s rifle. Then Harvey turned and walked out of the cabin, and she heard him climb the stairs back to the upper deck.

screamed. With her heart pounding, Terry Jo went back to her cabin. She crawled into her bunk. Soon, water coming into the cabin told her that Bluebelle was sinking. She was too afraid to move. However, Harvey was moving all over the place. Soon, she saw Harvey in the doorway holding her big brother’s rifle. Then Harvey turned and walked out of the cabin, and she heard him climb the stairs back to the upper deck.

With water reaching the top of her mattress, Terry Jo knew she had to get out. Wading through the water, she climbed to the deck again. On deck she saw that the ship’s dinghy and rubber life raft were floating beside the boat. “Is the ship sinking?” she called out. “Yes!” Harvey shouted, coming up from behind her. He pushed the line to the dinghy into her hands. “Hold this!” he shouted. Numb from shock, Terry Jo let the line slip through her fingers. The dinghy slowly drifted away from the sinking Bluebelle. Harvey jumped overboard to catch it, and Terry Jo watched him swim after the dinghy and disappear into the night. She remembered the cork life float that was kept lashed to the top right side of the main cabin, which was now just barely above-water. She scrambled to the small, oblong float and quickly untied it. Just as the float came free, the boat deck sank beneath her feet. She pushed the float into the open water, and climbed onto the float. One of its lines snagged on the sinking ship. For a moment, she and the float were pulled underwater as the Bluebelle went down. Then the line came free, and they popped back to the surface. She huddled low on the float, afraid that the captain might be coming back. She had no water, no food, and nothing to protect her from the cold. The night was so dark that she couldn’t see anything.

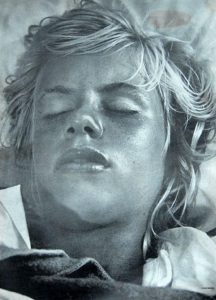

For three days Terry Jo was battered by the salt water, and scorched by the sun…her only companions, a pod of porpoises. She had no food or water. Each day brought her closer to death. On Tuesday, a small red plane circled overhead. She waved at it for a long time with her blouse. The plane passed directly over her, but at an angle that made it impossible for the pilots to see her. When the sun rose on Thursday, she did not feel its burning rays. She was in a deep sleep close to death. Only the faintest spark of life was left. About midmorning she emerged from her stupor and opened her eyes. A huge shadow loomed above her like a great beast. Its rumble was so deep that she could feel its pounding rhythm in her chest. It seemed like a dream, until she looked up to the top of that great wall, and saw heads and waving arms. She could hear voices shouting. Finally, she felt herself lifted from the water. She passed out again. Terry Jo spent 11 days in a Miami hospital but had no permanent injuries

The day after the Bluebelle went down, an oil tanker spotted Harvey. When the captain pulled the tanker closer, he yelled, “My name is Julian Harvey. I am master of the Bluebelle.” In the days that followed, Harvey told the Coast Guard in Miami that he was the sole survivor of a grave accident. In the middle of the previous night, he said that a sudden squall damaged the sailboat. His wife, Mary Dene, and the Duperraults were injured when the masts and rigging collapsed. Gas lines in the engine room ruptured, and the ship caught fire as it sank. Harvey said he had managed to get in the dinghy, but tangled rigging trapped everyone else on board. A few days later, staying at the Sandman Hotel, Harvey heard that Terry Jo had survived. The next day, a maid at the hotel found Harvey’s bloody, lifeless body on the floor. He had killed himself.

A week after her rescue, officials questioned Terry Jo in her hospital bed. Her story, disproved Harvey’s account. Her father, mother, brother, and younger sister, along with Mary Dene Harvey, had been slaughtered aboard the Bluebelle, at the hands of Julian Harvey. The police suspect that Harvey killed his wife to collect money from her life insurance, and one theory suggests that Duperrault caught Harvey in the act, prompting the other murders. Terry Jo returned to Green Bay to live with her father’s sister and three cousins. When she was 12, she changed her name to Tere. Nearly 50 years later, in 2010, Tere finally revealed the details of the night her family was killed and her days spent drifting in open water in her book, Alone: Orphaned on the Ocean.

Plane crashes are always tragic events. The loss of life and property is devastating. Sometimes, however, a pilot and his crew are able to pull off a landing in unbelievable circumstances. Something like that leaves everyone from the passengers, families, the NTSB, and the world scratching their heads in disbelief. Years ago I watched a movie about just such a flight. The flight was Air Canada Flight 143. A couple of days ago, I saw that it was the 33rd anniversary of that flight which occurred on July 23, 1983, and I thought about what a miracle that whole situation was. Canada Air had just made the conversion from pounds of fuel to kilograms of fuel. Unfortunately, as is often the case in these types of conversions, things were not converting as smoothly as the airline had hoped. On 22 July 1983, Air Canada’s Boeing 767, registered as C-GAUN, c/n 22520/47, from Toronto to Edmonton where it underwent routine checks. The next day, it was flown to Montreal. Following a crew change, it departed Montreal as Flight 143 for the return trip to Edmonton via Ottawa, with Captain Robert (Bob) Pearson and First Officer Maurice Quintal at the controls. The crew had been somewhat leery of taking off with the fuel indicator taped off as inoperable. It would seem logical to most of us that Air Canada should have waited until all systems were operable before using the plane, but that was not the case.

Plane crashes are always tragic events. The loss of life and property is devastating. Sometimes, however, a pilot and his crew are able to pull off a landing in unbelievable circumstances. Something like that leaves everyone from the passengers, families, the NTSB, and the world scratching their heads in disbelief. Years ago I watched a movie about just such a flight. The flight was Air Canada Flight 143. A couple of days ago, I saw that it was the 33rd anniversary of that flight which occurred on July 23, 1983, and I thought about what a miracle that whole situation was. Canada Air had just made the conversion from pounds of fuel to kilograms of fuel. Unfortunately, as is often the case in these types of conversions, things were not converting as smoothly as the airline had hoped. On 22 July 1983, Air Canada’s Boeing 767, registered as C-GAUN, c/n 22520/47, from Toronto to Edmonton where it underwent routine checks. The next day, it was flown to Montreal. Following a crew change, it departed Montreal as Flight 143 for the return trip to Edmonton via Ottawa, with Captain Robert (Bob) Pearson and First Officer Maurice Quintal at the controls. The crew had been somewhat leery of taking off with the fuel indicator taped off as inoperable. It would seem logical to most of us that Air Canada should have waited until all systems were operable before using the plane, but that was not the case.

The flight seemed to be going smoothly, but about half way between Montreal and Edmonton, at an altitude on 41,000 feet, the aircraft’s cockpit warning system sounded, indicating a fuel pressure problem on the aircraft’s left side. Assuming a fuel pump had failed, the pilots turned it off, since gravity should feed fuel to the aircraft’s two engines. In most situations, that would have worked, but when the plane was fueled, the technician failed to accurately convert the fuel from pounds to kilograms, and the plane had run out of fuel. Running out of fuel  in a small plane, flying at much lower altitudes has been known to get people killed, but this was a Boeing 767, and it was at an altitude of 41,000 feet. This had all the makings of a disaster…but somehow, that was not what happened. In this case, the event would prove to be the finest hour for the pilot and crew.

in a small plane, flying at much lower altitudes has been known to get people killed, but this was a Boeing 767, and it was at an altitude of 41,000 feet. This had all the makings of a disaster…but somehow, that was not what happened. In this case, the event would prove to be the finest hour for the pilot and crew.

The passengers on this plane had the unusual advantage of having at the controls, a pilot who was an experienced glider pilot. Now, as you know gliders have no fuel in them. You are pulled into the air by another plane and then released to glide in for a landing. That’s an easy enough task for a trained glider pilot in a glider plane, but this was a modern day, wide body jet. The idea of gliding this plane in for a safe landing was…well, unheard of. Robert “Bob” Pearson was that pilot, and with the help of his crew and an air traffic controller, he safely glided the plane into an abandoned Royal Canadian Air Force airstrip that was being used as a drag strip…at the very moment of the landing of the plane. The men could not see that, however, until they were almost on top of the people. Thankfully, the people on the runway saw the plane and got out of the way.

The crew had hoped to make Winnipeg, but with the best glide speed and the rate of descent, there was no way. Then, Quintal remembered Gimli, and the abandoned strip became their last hope. They were too high for it, so Pearson performed a slip, which is a glide maneuver to increase drag, causing the plane to lose altitude quickly. To add to the problem, the nose gear came down, but did not lock as the rest of the gear had. Could things have been more dire? In the end, Captain Pearson executed the landing perfectly, in spite of all of the problems, and the fact that the Winnipeg Sports Car Club was on the field with everything needed to assist in

this emergency, the plane landed without a single death in the plane or on the ground, and the fuel starvation scenario became part of the pilots training in their simulators. The first pilots to try the program in the simulator all crashed, and believed that it was an impossible scenario, until they were told that it had happened, and that the pilot landed safely. The flight has since been dubbed the Gimli Glider. And, that’s a miracle for the books.

this emergency, the plane landed without a single death in the plane or on the ground, and the fuel starvation scenario became part of the pilots training in their simulators. The first pilots to try the program in the simulator all crashed, and believed that it was an impossible scenario, until they were told that it had happened, and that the pilot landed safely. The flight has since been dubbed the Gimli Glider. And, that’s a miracle for the books.