pawn

Some people seem to have an exceptional mind. They might be a genius, or they might just be very good at one thing or a few things. Whatever the case may be, they are virtually impossible to beat at that one thing. The game of chess is one that many people don’t understand how to play. I played it many years ago, but I can’t say that I was ever very good at. I could play, and I could beat some players, provided they were not better than novice level. But, there are chess players who could only be classified as genius when it comes to the game of chess.

Some people seem to have an exceptional mind. They might be a genius, or they might just be very good at one thing or a few things. Whatever the case may be, they are virtually impossible to beat at that one thing. The game of chess is one that many people don’t understand how to play. I played it many years ago, but I can’t say that I was ever very good at. I could play, and I could beat some players, provided they were not better than novice level. But, there are chess players who could only be classified as genius when it comes to the game of chess.

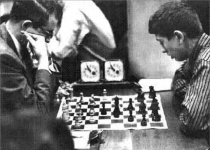

Two such players were 26 year old Donald Byrne, who on October 17, 1956, took part in what was destined to be called The Game of the Century. In the end Byrne would lose the game to 13 year old Bobby Fischer, in the Rosenwald Memorial Tournament in New York City. The competition took place at the Marshall Chess Club. It was nicknamed “The Game of the Century” by Hans Kmoch in Chess Review. Kmoch wrote, “The following game, a stunning masterpiece of combination play performed by a boy of 13 against a formidable opponent, matches the finest on record in the history of chess prodigies.”

I don’t suppose Mr Byrne expected to be bested by a 13 year old boy, nor did he likely appreciate all the publicity that came of his unfortunate loss. Donald Byrne was one of the leading American chess masters at the time of this game. He won the 1953 U.S. Open Championship, and later represented the United States in the 1962, 1964, and 1968 Chess Olympiads. He became an International Master in 1962, and probably would have risen further if not for ill health. Robert “Bobby” Fischer (1943–2008) was at this time a promising young master. Following this game, he had a meteoric rise, winning the 1957 U.S. Open on tiebreaks, winning the 1957–58 U.S. (Closed) Championship, and all seven later championships in which he played, qualifying for the Candidates Tournament and becoming in 1958 the world’s youngest grandmaster at the age of 15. He won the world championship in 1972, and is considered by many to be the greatest chess player of all time.

According to Kmoch’s recap of the game, Fischer, who was playing Black, demonstrated noteworthy innovation  and improvisation. Byrne, who was playing White, after a standard opening, makes a seemingly minor mistake on move 11, losing a tempo by moving the same piece twice. Fischer pounces with brilliant sacrificial play, culminating in a queen sacrifice on move 17. Byrne captures the queen, but Fischer gets far too much material for it…a rook, two bishops, and a pawn. At the end, Fischer’s pieces coordinate to force checkmate, while Byrne’s queen sits, useless, on the other side of the board. Responding to an interviewer’s question about how he was able to bring off such a brilliant win, Fischer said, “I just made the moves I thought were best. I was just lucky.” Looking at his lifelong record, I doubt that anyone would agree with that statement. Fischer’s wins were anything but luck. They were rather a matter of skill, focus, and a strategic mind.

and improvisation. Byrne, who was playing White, after a standard opening, makes a seemingly minor mistake on move 11, losing a tempo by moving the same piece twice. Fischer pounces with brilliant sacrificial play, culminating in a queen sacrifice on move 17. Byrne captures the queen, but Fischer gets far too much material for it…a rook, two bishops, and a pawn. At the end, Fischer’s pieces coordinate to force checkmate, while Byrne’s queen sits, useless, on the other side of the board. Responding to an interviewer’s question about how he was able to bring off such a brilliant win, Fischer said, “I just made the moves I thought were best. I was just lucky.” Looking at his lifelong record, I doubt that anyone would agree with that statement. Fischer’s wins were anything but luck. They were rather a matter of skill, focus, and a strategic mind.