panic

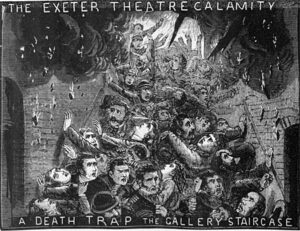

In American schools, and maybe in schools all over the world, children are used to the occasional fire drill, because it is a practice is designed to allow people to escape a fire, instead of losing their lives in a panic. Of course, this practice is fairly new, and came about after a number of fire disasters. One such disaster was the September 5, 1887, Exeter Theatre Royal fire in Exeter, England.

In American schools, and maybe in schools all over the world, children are used to the occasional fire drill, because it is a practice is designed to allow people to escape a fire, instead of losing their lives in a panic. Of course, this practice is fairly new, and came about after a number of fire disasters. One such disaster was the September 5, 1887, Exeter Theatre Royal fire in Exeter, England.

The fire broke out in the backstage area of the theatre during the production of “The Romany Rye” by George Robert Sims and produced by Wilson Barrett. When the fire was known, a panic ensued throughout the theatre. Whenever there is panic, someone is going to get hurt, or worse. In this case, 186 people died from a combination of the direct effects of smoke and flame, crushing and trampling, and trauma injuries from falling or jumping from the roof and balconies. It is such a sad situation, because if they had not panicked, it is likely that all or most of those would have survived. Of course, panic was not the only reason for the deaths, so we will never truly know if this could have been prevented. The Exeter Theatre Royal death toll makes it the worst theatre disaster, the worst single-building fire, and the third worst fire-related disaster in the history of the United Kingdom. Most of those who lost their lives were in the gallery of the theatre, which had only a single exit with several design flaws. The exit quickly became clogged with people trying to escape.

This was not the first time the Theatre Royal had been destroyed. The first Exeter Theatre Royal had been gutted by fire in 1885, and the new theatre was opened, on a new site, in 1886 to the design of well-known theatre architect CJ Phipps. The new theatre was leased exclusively to Sidney Herberte-Basing. The new  building was constructed from stone and red brick on the outside, but the inside was largely constructed of wood. Following the 1885 fire, the licensing authority of Exeter City Council ordered that the new theatre be constructed “in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Metropolitan Board of Works,” which was a statutory requirement in London under The Metropolitan Building Act 1855 (with theatre particulars added in the 1878 amendment), but not required in the regions. In his letter accompanying the plans to the Corporation Surveyor of Exeter City Council, Phipps directly states that the building met all the rules and requirements laid out, ans added that he had extensive experience in these types of construction. The letter stated, “…the theatre is designed in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Board of Works under the Act of 1878 and of the Lord Chamberlain – and having constructed some 40 theatres, I bring a somewhat large experience to bear on this subject.” – C.J. Phipps, Letter of 11 July 1885 from Phipps to the Corporation Surveyor of the City of Exeter.

building was constructed from stone and red brick on the outside, but the inside was largely constructed of wood. Following the 1885 fire, the licensing authority of Exeter City Council ordered that the new theatre be constructed “in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Metropolitan Board of Works,” which was a statutory requirement in London under The Metropolitan Building Act 1855 (with theatre particulars added in the 1878 amendment), but not required in the regions. In his letter accompanying the plans to the Corporation Surveyor of Exeter City Council, Phipps directly states that the building met all the rules and requirements laid out, ans added that he had extensive experience in these types of construction. The letter stated, “…the theatre is designed in accordance with the rules and regulations of the Board of Works under the Act of 1878 and of the Lord Chamberlain – and having constructed some 40 theatres, I bring a somewhat large experience to bear on this subject.” – C.J. Phipps, Letter of 11 July 1885 from Phipps to the Corporation Surveyor of the City of Exeter.

Nevertheless, during the licensing inspection, several deficiencies were noted and ordered to be corrected, including “installing an additional exit for the audience from the boxes, stalls, and pit, widening the exits to at  least 6 feet, changing some single leaf exit doors to double doors, and supplying 80 feet of hose for each hydrant (of which there were only two – one in the foyer and one in the “prompts” in front of the stage), rather than 40 feet which had been provided.” Unfortunately, there was no inspection of the stage, the mezzanine floor, or the fly galleries above the stage. There was only one exit with four right angled turns in it, from this area, and while two exits were called for, the idea was passed over because Phipps asserted “that a second exit was provided by climbing the railing at the front of the gallery and dropping to the second circle below.” That was, of course a crazy notion, that cost lives in the end. Apparently, this plan was accepted without further argument. In addition, there was to be an iron safety curtain, which was not fitted at the time of the fire, and a fire hydrant in the stage wings was on the plans of the theatre but never installed, despite Phipps being advised that the two hydrants installed were insufficient. In the end, the panic, along with the mishandled inspections and the improper plan design cost 186 people their lives.

least 6 feet, changing some single leaf exit doors to double doors, and supplying 80 feet of hose for each hydrant (of which there were only two – one in the foyer and one in the “prompts” in front of the stage), rather than 40 feet which had been provided.” Unfortunately, there was no inspection of the stage, the mezzanine floor, or the fly galleries above the stage. There was only one exit with four right angled turns in it, from this area, and while two exits were called for, the idea was passed over because Phipps asserted “that a second exit was provided by climbing the railing at the front of the gallery and dropping to the second circle below.” That was, of course a crazy notion, that cost lives in the end. Apparently, this plan was accepted without further argument. In addition, there was to be an iron safety curtain, which was not fitted at the time of the fire, and a fire hydrant in the stage wings was on the plans of the theatre but never installed, despite Phipps being advised that the two hydrants installed were insufficient. In the end, the panic, along with the mishandled inspections and the improper plan design cost 186 people their lives.

One of the most common practices of the school year is the routine fire drill. These days, children are well aware of what is going on, and often look forward to being able to vacate the classroom…even if only for a few minutes. The routine fire drill is designed to insure that the students leave the premises without panic, whether there is an actual fire or not. These drills were not always routine, the ensuing panic could be deadly.

One of the most common practices of the school year is the routine fire drill. These days, children are well aware of what is going on, and often look forward to being able to vacate the classroom…even if only for a few minutes. The routine fire drill is designed to insure that the students leave the premises without panic, whether there is an actual fire or not. These drills were not always routine, the ensuing panic could be deadly.

In 1851, in Greenwich Avenue school, located at 36 to 40 Greenwich Avenue. When the fire alarm sounded, the children panicked. They had not been trained to calmly exit the building, and in the ensuing panic, 40 children were killed. There was no fire, and the fire alarm had been set off by accident, but the children had no idea what to do, and so went running in fear. The deaths were horrible trample deaths. More children were injured.

The tragedy of 1851 was almost repeated in 1882, when a fire drill went off at Grammar School Number 41, at the same sight of the 1851 panic. The situation may have occurred on a different date, but the result was the same…panic. When the fire alarm sounded, someone cried, Fire!!” After that, chaos took over, and the same disaster could have happened, had not the teachers, janitor, firemen, and police stayed calm. Somehow they managed to calm the children down. The adults behaved with such rare intelligence and energy that the panic was stayed and nearly all the children reached the avenue unharmed. Grammar School Number 41 was an all-girl school. At the time of the panic 610 students were in the 11 classrooms of the primary school on the first floor, under Miss Susanna Whitney, and 669 were in the 19 classrooms of the grammar school on the second and third floors, under Miss Lizzie Cavannah. There was a female teacher in each of the classrooms.

Somehow, all of the 1200+ students got out alive. When the school reopened, an order was received from City Superintendent John Jasper to perfect the scholars in the fire drill. “Each scholar has a numbered peg on which to hang her clothes, and the fire drill consisted in sounding an alarm, when the scholars are required to get their clothes and collect their books and return to their seats. Meanwhile preparations were made for the teachers to be on the landings of the seven staircases, four of which are fire-proof, which lead to the four exits on Greenwich-avenue. At a signal the children were to rise and go out calmly. Going down the stairs one only was permitted to be on each side of the staircase, where there is a handrail, and the exit to the avenue was required to be in an orderly manner.”

Previously, the fire drill alarm was sounded on the tinkling class bells from bell handles in the assembly room of the primary and grammar departments. This was deemed unsafe, as it necessitated the pulling of as many handles as there were classrooms. It had to change. To make a simultaneous alarm, three large fire-gongs were installed, so that the whole school could be notified by pulling at three handles. It does not appear that the students knew of the new arrangement. Some of them had heard of the gongs, but they had not heard them strike, and they did not receive instructions about them, which would have helped immensely. It was agreed between Miss Whitney and Miss Cavannah that a fire drill should be held on a particular day. They believed that the 140 new and untrained students in the primary school and 90 new girls in the grammar school would follow the example of the trained students. At 2:40pm, Miss Cavannah had the alarm struck on the second and third floors. Six strokes were sounded on each gong. The deep, loud noise, resembling the clang of a fire engine gong, startled even the trained students, and as they whispered to each other “fire drill” in going for their clothes the untrained students misunderstood them, and believed that the school was on fire, and that the noise of the gongs was the bells of the engines summoned to the school. There was a panic immediately, and 50 fearful girls ran screaming and bareheaded from the grammar school to the street before the teachers could spring to the doorways, bar exit, and command order. The screaming and confusion overheard alarmed  the students and teachers in the primary school, but the doors were guarded before more than 25 or 30 children escaped. For several minutes the teachers had hard work to keep back the imprisoned children. The trained students were as alarmed as the new ones, and some of them wept and begged piteously as they, despite the assurances of their teachers, who all behaved bravely except for one instance, that of a new instructress, who for a time did not understand the situation. Some of the children even ran home and told their parents and neighbors that the school was on fire and the children were burning. It almost created a panic of the whole town. It quickly became clear that prior to the first drill, the students needed instruction on procedure.

the students and teachers in the primary school, but the doors were guarded before more than 25 or 30 children escaped. For several minutes the teachers had hard work to keep back the imprisoned children. The trained students were as alarmed as the new ones, and some of them wept and begged piteously as they, despite the assurances of their teachers, who all behaved bravely except for one instance, that of a new instructress, who for a time did not understand the situation. Some of the children even ran home and told their parents and neighbors that the school was on fire and the children were burning. It almost created a panic of the whole town. It quickly became clear that prior to the first drill, the students needed instruction on procedure.

At a time when television was in the very early stages of its existence, and not really available to the public, people got their entertainment from the radio. People listened to everything from news, to music, to fictional shows, which were of course, acted out only by the actors verbalizing the parts. Most of the shows were a normal story line, probably often Westerns, and so the people were able to distinguish the fiction from the news. On this day, October 30, 1938, all that changed, when the Mercury Theater company decided to put Orson Welles on the radio in the H.G. Wells novel, War Of The Worlds. Welles had previously been the voice of The Shadow, which apparently was not a show that the people took seriously, even though it was scary. The same would not be true with War Of The Worlds, which was a dramatization of a Martian invasion of Earth. I find it odd that people would believe either show, but that is beside the point.

At a time when television was in the very early stages of its existence, and not really available to the public, people got their entertainment from the radio. People listened to everything from news, to music, to fictional shows, which were of course, acted out only by the actors verbalizing the parts. Most of the shows were a normal story line, probably often Westerns, and so the people were able to distinguish the fiction from the news. On this day, October 30, 1938, all that changed, when the Mercury Theater company decided to put Orson Welles on the radio in the H.G. Wells novel, War Of The Worlds. Welles had previously been the voice of The Shadow, which apparently was not a show that the people took seriously, even though it was scary. The same would not be true with War Of The Worlds, which was a dramatization of a Martian invasion of Earth. I find it odd that people would believe either show, but that is beside the point.

Orson Welles was just 23 years old when War Of The Worlds was first broadcast on air, but he had been in radio for several years. The War Of The Worlds show was not planned to be a radio hoax, and Welles had no idea of the havoc the show would cause. The show began on Sunday, October 30, at 8 pm. A voice announced: “The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theater on the air in ‘War of the Worlds’ by H.G. Wells.” Sunday evening was considered prime time in the world of 1938 radio. Apparently, the show prior to this one wasn’t very good, and so many people tuned in too late to hear the announcement that the War Of The Worlds was a science fiction story, and the story was already underway. Welles introduced his radio play with a spoken introduction, followed by an announcer reading a weather report. Then, the announcer seemingly abandoned the storyline, and took listeners to “the Meridian Room in the Hotel Park Plaza in downtown New York, where you will be entertained by the music of Ramon Raquello and his orchestra.” Dance music played for a while, and then the scare began. An announcer broke in to report that “Professor Farrell of the Mount Jenning Observatory” had detected explosions on the planet Mars. Then the dance music came back on, followed by another interruption in which listeners were informed that a large meteor had crashed into a farmer’s field in Grovers Mills, New Jersey. At this point, those who tuned in late, were wondering what was going on, and maybe the ones who tuned in on time were wondering too.

Soon, an announcer was at the crash site describing a Martian emerging from a large metallic cylinder. “Good heavens,” he declared, “something’s wriggling out of the shadow like a gray snake. Now here’s another and another one and another one. They look like tentacles to me…I can see the thing’s body now. It’s large, large as a bear. It glistens like wet leather. But that face, it… it…ladies and gentlemen, it’s indescribable. I can hardly force myself to keep looking at it, it’s so awful. The eyes are black and gleam like a serpent. The mouth is kind of V-shaped with saliva dripping from its rimless lips that seem to quiver and pulsate.” The story continued when the announcer said, “The Martians mounted walking war machines and fired ‘heat-ray’ weapons at the puny humans gathered around the crash site. They annihilated a force of 7,000 National Guardsman, and after being attacked by artillery and bombers the Martians released a poisonous gas into the air.” Then they declared that “Martian cylinders” had landed in Chicago and St. Louis. The radio play was extremely realistic. Welles even used sophisticated sound effects and his talented actors did an excellent job portraying terrified announcers and other characters. An announcer reported that “widespread panic had broken out in the vicinity of the landing sites, with thousands desperately trying to flee.”

In fact, that was not far from the truth, because as many as a million radio listeners believed the invasion was real. Panic broke out across the country. In this day and age, this all seems crazy, because we have seen every possible invasion story imaginable, but back then, not so much. In New Jersey, terrified people reportedly hit the highways seeking a way of escape from the alien invasion. People begged police for gas masks to save them from the toxic gas and asked electric companies to turn off the power so that the Martians wouldn’t see  their lights. One woman ran into an Indianapolis church where evening services were being held and yelled, “New York has been destroyed! It’s the end of the world! Go home and prepare to die!”

their lights. One woman ran into an Indianapolis church where evening services were being held and yelled, “New York has been destroyed! It’s the end of the world! Go home and prepare to die!”

When the studio heard of the panic, Orson Welles went on the air as himself to remind listeners that it was just fiction. It was reported that the show caused suicides, but that was never confirmed. The Federal Communications Commission investigated the program, but found no law was broken. Networks did agree to be more cautious in their programming in the future. Orson Welles worried that the controversy would ruin his career, but the opposite was true. The publicity helped him to land a contract with a Hollywood studio, and in 1941 he wrote, directed, produced, and starred in Citizen Kane…a movie that many have called the greatest American film ever made. Of course, there are those who said that the whole thing was a hoax, but I guess we will never know for sure.