officers

Out of necessity, comes innovation. Many of history’s great problems were solved because it was a necessity. For the most part, Britain has maintained a small British Army. Somehow, probably mostly due to geography, rather than might, the British Royal Navy was able to protect the island nation from its enemies quite well…until World War I, that is, and indeed, young men did not feel the need to join the army due to patriotic duty, but rather due to a shortage of other working options. In fact, a career in the military wasn’t looked upon favorably at all.

Out of necessity, comes innovation. Many of history’s great problems were solved because it was a necessity. For the most part, Britain has maintained a small British Army. Somehow, probably mostly due to geography, rather than might, the British Royal Navy was able to protect the island nation from its enemies quite well…until World War I, that is, and indeed, young men did not feel the need to join the army due to patriotic duty, but rather due to a shortage of other working options. In fact, a career in the military wasn’t looked upon favorably at all.

When World War I broke out in 1914, Britain suddenly experienced a huge shortage of trained military personnel, especially officers. This was further complicated by heavy casualties in the British Expeditionary Force in France, which dwindled the limited supply even further. That meant to keep up, they were going to need a large number of officers to be sourced and trained quickly. Their only real solution was to take young upper-class men and put them through officer training. These were teenagers, young men still in school, but it was necessary, and so schooling was either ended or postponed.

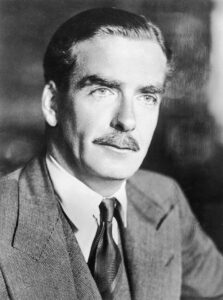

During World War I, as was seen with the RMS Titanic, class was considered of the utmost importance. In Britain, only a gentleman could be an officer. The working-class and lower-class men were put in as the average  soldier. Somehow it was thought that “Short of actual military credentials, a person’s schooling was thought to be a reasonable litmus test for leadership.” To further confuse things in the minds of most Americans these days, a public school in Britain is actually a very exclusive private institution. Eton College, a private institution attended by no fewer than 20 prime ministers, is probably the best example of that. Anthony Eden, who would later become prime minister, was an Eton alum, who also served as an officer in the British Army.

soldier. Somehow it was thought that “Short of actual military credentials, a person’s schooling was thought to be a reasonable litmus test for leadership.” To further confuse things in the minds of most Americans these days, a public school in Britain is actually a very exclusive private institution. Eton College, a private institution attended by no fewer than 20 prime ministers, is probably the best example of that. Anthony Eden, who would later become prime minister, was an Eton alum, who also served as an officer in the British Army.

When World War I broke out, Eden was just 17, and after a rushed officer training course, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant a year later. It seems strange and almost reckless to have upper-class teenagers leading working-class soldiers, but in this case, it actually worked well. The teenage future prime minister recalled his men “were tolerant of me as we were all learning together.” Eden quickly learned that “As long as the officer showed proper concern for the well-being of his men and courage under fire, the men in turn would show great loyalty.”

The commissioned officers were also helped enormously by the noncommissioned officers. The  noncommissioned officers were usually working-class men who had been promoted from the ranks after showing leadership abilities throughout their military careers. Thankfully so, because as Eden would later recall of a sergeant named Arnold Rushworth in his post-war memoirs, “He was my right hand and no small part of my brain as well.” I’m sure that part of the reason this plan of upper-class men becoming officers worked was the sheer compassion of the working-class men, who helped them along the way. It was the way of the times, and I suppose that the men simply accepted their “position” in life as being the way things were, and that it could not be changed.

noncommissioned officers were usually working-class men who had been promoted from the ranks after showing leadership abilities throughout their military careers. Thankfully so, because as Eden would later recall of a sergeant named Arnold Rushworth in his post-war memoirs, “He was my right hand and no small part of my brain as well.” I’m sure that part of the reason this plan of upper-class men becoming officers worked was the sheer compassion of the working-class men, who helped them along the way. It was the way of the times, and I suppose that the men simply accepted their “position” in life as being the way things were, and that it could not be changed.

When dealing with one of the world’s more horrible murdering dictators, armies will try just about anything to take them down. Adolf Hitler seemed to be one of those dictators who just couldn’t be taken down. He even flaunted it in the face of his enemies, sending it across the airways, that he was still alive, even after they tried to kill him again. July 21, 1944, was one of those times when Adolf Hitler took to the airwaves to announce that the attempt on his life has failed and that “accounts will be settled.” Not only was Hitler good at dodging a bullet, but he was arrogant too.

When dealing with one of the world’s more horrible murdering dictators, armies will try just about anything to take them down. Adolf Hitler seemed to be one of those dictators who just couldn’t be taken down. He even flaunted it in the face of his enemies, sending it across the airways, that he was still alive, even after they tried to kill him again. July 21, 1944, was one of those times when Adolf Hitler took to the airwaves to announce that the attempt on his life has failed and that “accounts will be settled.” Not only was Hitler good at dodging a bullet, but he was arrogant too.

On this particular day, Hitler had survived the bomb that was meant to take his life. He didn’t get off unscathed, however. Hitler suffered punctured eardrums, some burns and minor wounds, but nothing that would keep him from regaining control of the government and finding the rebels. In fact, it only took a mere 11½ hours, to put down the coup d’etat, that was supposed to accompany the planned assassination of Hitler. In Berlin, Army Major Otto Remer, believed to be apolitical by the conspirators and willing to carry out any orders given him, was told that the Fuhrer was dead and that he, Remer, was to arrest Joseph Goebbels, Minister of Propaganda. But Goebbels had news for Remer.  Hitler was alive. He proved it, by getting him on the phone, because the rebels had forgotten to cut the phone lines. Hitler immediately gave Remer direct orders to put down any army rebellion and to follow only his orders or those of Goebbels or Himmler. Remer obeyed and let Goebbels go. The SS then snapped into action, arriving in Berlin, which was now in chaos, just in time to convince many high German officers to remain loyal to Hitler.

Hitler was alive. He proved it, by getting him on the phone, because the rebels had forgotten to cut the phone lines. Hitler immediately gave Remer direct orders to put down any army rebellion and to follow only his orders or those of Goebbels or Himmler. Remer obeyed and let Goebbels go. The SS then snapped into action, arriving in Berlin, which was now in chaos, just in time to convince many high German officers to remain loyal to Hitler.

What followed forth rebels was hideous. Arrests, torture sessions, executions, and suicides were the order of the day. Count Claus von Stauffenberg, was the man who actually planted the explosive in the room with Hitler. He had insisted to his co-conspirators that “the explosion was as if a 15 millimeter shell had hit. No one in that room can still be alive.” But it was Stauffenberg who would not be alive for much longer. He was shot dead the very day of the attempt by a pro-Hitler officer. There was no trial, and no second chance given.  The plot was completely demolished.

The plot was completely demolished.

Then, Hitler set out to restore calm and confidence to the German civilian population. At 1am on July 21, Hitler’s voice broke through the radio airwaves: “I am unhurt and well…. A very small clique of ambitious, irresponsible…and stupid officers had concocted a plot to eliminate me… It is a gang of criminal elements which will be destroyed without mercy. I therefore give orders now that no military authority…is to obey orders from this crew of usurpers… This time we shall settle account with them in the manner to which we National Socialists are accustomed.” The attempt on his life was over, and Hitler would live…to die another day.

Israel Putnam Spencer, who is my sixth cousin twice removed, was a writer in his own right. He wrote a journal of sorts that dated back to his earliest recollections, beginning at about four or five years of age. Not everyone can remember very much about themselves at that age, although I think a number of us can. Usually it is some traumatic even, such as illness, a death, or as in my cast, an accident, in which I lost a fight with an escalator. For Israel, it was both illness and death. Israel states that he was just “getting over a spell of sickness” in the town of DeRuyter, Madison County, New York. He talks of moving to Corning, Steuben County, New York where the family lived another four years. This place had no stove, so cooking was done over the fire in the fireplace. It was in Corning that he and his sister got the measles, and his aunt, his mother’s sister died…probably also of measles, as they were very dangerous in those days. His writings tell of hard times…of moving to live with his mother’s brother, Frank Lewis. Hard times in that after finding a dog and being so excited to have a pet, they had to give the dog to a cousin. I’m sure these things all seemed extra hard to a young boy of about nine or ten. Yet, in the midst of those hard times, the family arrived at Israel’s Uncle Frank’s house, to find the dog, that they hadn’t seen in two years…and the dog remembered them, and was so excited to see them. That friendship must have felt like the sun coming out after a long raging storm.

Israel Putnam Spencer, who is my sixth cousin twice removed, was a writer in his own right. He wrote a journal of sorts that dated back to his earliest recollections, beginning at about four or five years of age. Not everyone can remember very much about themselves at that age, although I think a number of us can. Usually it is some traumatic even, such as illness, a death, or as in my cast, an accident, in which I lost a fight with an escalator. For Israel, it was both illness and death. Israel states that he was just “getting over a spell of sickness” in the town of DeRuyter, Madison County, New York. He talks of moving to Corning, Steuben County, New York where the family lived another four years. This place had no stove, so cooking was done over the fire in the fireplace. It was in Corning that he and his sister got the measles, and his aunt, his mother’s sister died…probably also of measles, as they were very dangerous in those days. His writings tell of hard times…of moving to live with his mother’s brother, Frank Lewis. Hard times in that after finding a dog and being so excited to have a pet, they had to give the dog to a cousin. I’m sure these things all seemed extra hard to a young boy of about nine or ten. Yet, in the midst of those hard times, the family arrived at Israel’s Uncle Frank’s house, to find the dog, that they hadn’t seen in two years…and the dog remembered them, and was so excited to see them. That friendship must have felt like the sun coming out after a long raging storm.

Soon things were looking up for the family, and Israel’s dad bought a farm where the family lived until Israel was fourteen and then he traded that farm for a 100 acre farm just a sort distance away. That farm brought about a big change for the Israel and his brothers because they now have to work the farm, in order to keep up. They went to school in the winter and worked the farm in summer. Then Israel writes of reaching an age where he got a “big head” like most boys did at about 15 to 18 years of age. He said that he got to a point where he was convinced that he knew more than the teachers and his parents combined, and so he quit school at 17 years old. He got odd jobs, and made about $15.00 a month…about average for a 17 year old in those days, I suppose, but maybe less than if he had more schooling…these days anyway.

Then came the biggest change of Israel’s life…the Civil War started in 1861. His oldest brother, Morton Spencer  enlisted in Company E, 23rd New York Infantry for two years. Shortly thereafter, Israel’s brother Fred Spencer enlisted, and Israel joined him. It was August 6th of 1862, and Israel was 18 years and 2 months old. Israel tells of his time spent in the war, with an insider’s view that most of us never got to hear about. The northern army, and I suspect the southern army as well, were having trouble keeping their officers. Back then, they didn’t have the came controls over the people in the army. A person could be missing for weeks before anyone really got word of it. Of course, when an officer goes missing, and you are one of his men, you know it, and that is what happened at times…especially when the war put brother against brother, as was the case in the Civil War. He survived the war, as did his brothers, but those were days of hunger and lack. He chose in later years, not to talk about them much, because who would want to remember such a time. He did write about those day, and there are many more tales to tell of the Civil War, but that is a story for another day.

enlisted in Company E, 23rd New York Infantry for two years. Shortly thereafter, Israel’s brother Fred Spencer enlisted, and Israel joined him. It was August 6th of 1862, and Israel was 18 years and 2 months old. Israel tells of his time spent in the war, with an insider’s view that most of us never got to hear about. The northern army, and I suspect the southern army as well, were having trouble keeping their officers. Back then, they didn’t have the came controls over the people in the army. A person could be missing for weeks before anyone really got word of it. Of course, when an officer goes missing, and you are one of his men, you know it, and that is what happened at times…especially when the war put brother against brother, as was the case in the Civil War. He survived the war, as did his brothers, but those were days of hunger and lack. He chose in later years, not to talk about them much, because who would want to remember such a time. He did write about those day, and there are many more tales to tell of the Civil War, but that is a story for another day.