new york city

While I’m not a bicycle fan, I know that a lot of people really love to go cycling. In the United States, the recreational bicycling fad began on February 11, 1878, when the Boston Bicycle Club became the first organization for recreational cyclists. The fad caught on, and the following year, a club was also formed in Buffalo, New York, followed by a club in New York City in 1880. Soon, clubs were starting up everywhere, as middle-class participation in cycling grew. There were literally hundreds of cycling clubs formed across the United States.

While I’m not a bicycle fan, I know that a lot of people really love to go cycling. In the United States, the recreational bicycling fad began on February 11, 1878, when the Boston Bicycle Club became the first organization for recreational cyclists. The fad caught on, and the following year, a club was also formed in Buffalo, New York, followed by a club in New York City in 1880. Soon, clubs were starting up everywhere, as middle-class participation in cycling grew. There were literally hundreds of cycling clubs formed across the United States.

Once formed, the Boston Bicycle Club organized various rides. They quicky organized events…from tricycle races to 100-mile rides. The trend caught on and less than 20 years after its founding, more than 100 cycling clubs had formed in Massachusetts alone. In fact, according to the Massachusetts Historical Society, the clubs catered to rider expertise, gender, nationality and more. The early bicycles resembled what we might view as a tricycle today, with an oversized front wheel. Nevertheless, they still only had two wheels, and not the three that are found on a tricycle.

In October 1879, Boston Bicycle Club members rode an 87-mile round trip course through the city and its suburbs in an event with the Massachusetts Cycling Club. For short distances, the cyclists achieved speeds of 16 mph, according to the Boston Post. While the club was not necessarily considered an exercise club, the members did a lot of training to prepare for the different events. Of course, when you think about it, you would  need to practice and train to get used to the Victorian-style penny farthings, as they are called.

need to practice and train to get used to the Victorian-style penny farthings, as they are called.

Over the years, the two-wheeler evolved, and the oversized front wheel became a thing of the past, except on vintage bicycles, called Victorian Style Penny Farthings. The changes to the bicycle became a great improvement over the course of a century, thanks to several different inventors. Every so often, someone might decide to test their horses against the bicycles, such as the man in Watertown who was “driving a spirited horse engaged in a race with the riders and was beaten by Terront, the French rider, in about three-quarters of a mile,” according to the Post. It’s funny that the old “horse and buggy crowd” would feel the need to pit their horses against the bicycles. Still, you would have expected the horses to win the race and maybe they would have in a longer distance. Or maybe the horses were a little bit spooked by the contraption beside them. Either way, they lost the race that day.

In 1896, Boston highlighted the club that bore their name. The Boston Globe highlighted the work of the first club in the United States. Since then, “The name and fame of the Boston Bicycle Club has gone all over this fair land, and is spreading to foreign shores, whither some to its members have carried it.” The early bicycle clubs were great advocates for better roads that would be safer for bicyclists. When the automobile entered the scene, bicyclists would quickly find themselves caught between the road, and the cars that now

occupied it with them. Many is the bicyclist that has lost his life at the hands, or wheels of a car. Of course, with the rise of automobiles early in the 20th century, the popularity of recreational cycling declined. In more recent years, bicycling as started to make a comeback, both in the exercise arena and the recreational arena.

occupied it with them. Many is the bicyclist that has lost his life at the hands, or wheels of a car. Of course, with the rise of automobiles early in the 20th century, the popularity of recreational cycling declined. In more recent years, bicycling as started to make a comeback, both in the exercise arena and the recreational arena.

These days, we all know what mass transit is. It’s about taking a trip on a plane, train, ship, or even a bus. Certainly, trains existed prior to 1832, but they were not designed for cross-town travel back then. On November 14, 1832, all that changed when the New York and Harlem Railroad in New York City introduced the nation’s first horse-drawn streetcar. The streetcar service was launched on the Bowery and Fourth Avenue in Manhattan, spanning from Prince to 14th Street, and with that, it became the city’s inaugural mass transit system. The fare for a ride was set at 12.5 cents.

These days, we all know what mass transit is. It’s about taking a trip on a plane, train, ship, or even a bus. Certainly, trains existed prior to 1832, but they were not designed for cross-town travel back then. On November 14, 1832, all that changed when the New York and Harlem Railroad in New York City introduced the nation’s first horse-drawn streetcar. The streetcar service was launched on the Bowery and Fourth Avenue in Manhattan, spanning from Prince to 14th Street, and with that, it became the city’s inaugural mass transit system. The fare for a ride was set at 12.5 cents.

The streetcar was named “John Mason” after the President of Chemical Bank, a prosperous New York businessman and railroad co-founder who financed its creation. It was essentially a horse-drawn bus with seating for about a dozen passengers. However, as reported by the New York Herald, this did not deter people from crowding in, “People are packed into streetcars like sardines in a box, with perspiration for oil. The seats being more than filled, the passengers are placed in rows down the middle, where they hang on by the straps, like smoked hams in a corner grocery.” No one thought about the problems, and in fact dangers of overcrowding, and as it turns out those dangers did not materialize anyway, so the ride, overcrowding and all, was a beloved pastime.

Horse-drawn carriages had always existed in New York City, but the omnibus was different because it ran along a designated route and was a more affordable option. “Omni” meant the bus carried everyone and anyone. The ride was cushioned with steel springs, but wheels were solid metal and wood. I can imagine the rough ride its passengers must have experienced, and the amount of effort needed by the draft animals to pull the oversize coaches along New York City’s cobblestone, unfinished, and litter-strewn streets. While riding was a trick sometimes, getting off was just as strange. To signal their desire to disembark from the large stagecoach, passengers would pull on a leather strap connected to the driver’s ankle. Imagine how annoying that constant pulling on the ankle must have been for the driver. I suppose he got used to it, but to me it seems like it would be a huge annoyance.

The next step took over 50 years, but in 1883, New York saw its first steam-powered streetcar, which replaced

the horse-drawn omnibus. From there, change was rapid. By 1909, electric trolleys were introduced to the city. Even the local baseball team got in on the streetcar craze. Baseball historians tell of the Brooklyn Dodgers, originally the “Trolley Dodgers,” who earned their name because the borough’s baseball team fans quite often had to navigate through busy streetcar traffic.

the horse-drawn omnibus. From there, change was rapid. By 1909, electric trolleys were introduced to the city. Even the local baseball team got in on the streetcar craze. Baseball historians tell of the Brooklyn Dodgers, originally the “Trolley Dodgers,” who earned their name because the borough’s baseball team fans quite often had to navigate through busy streetcar traffic.

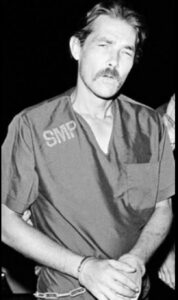

Jack Henry Abbott spent nearly his entire life behind bars. Sent to a Utah reform school at nine, he was later arrested and convicted of forgery shortly after his release. During his sentence at the Utah state penitentiary, he killed an inmate in 1966, claiming self-defense, which nevertheless resulted in an additional 14-year sentence. In 1971, Abbott fled from incarceration and committed a bank robbery in Denver, only to be apprehended later.

Jack Henry Abbott spent nearly his entire life behind bars. Sent to a Utah reform school at nine, he was later arrested and convicted of forgery shortly after his release. During his sentence at the Utah state penitentiary, he killed an inmate in 1966, claiming self-defense, which nevertheless resulted in an additional 14-year sentence. In 1971, Abbott fled from incarceration and committed a bank robbery in Denver, only to be apprehended later.

While incarcerated again, Abbott learned of Norman Mailer’s project on Gary Gilmore, who was awaiting execution in Utah, and started sending Mailer detailed letters about his alleged mistreatment behind bars. Mailer, who strangely thought that Abbott had talent as a writer, persuaded the New York Review of Books to publish some of his letters. Subsequently, Random House published Abbott’s book, “In the Belly of the Beast.” Pointing out Abbott’s potential in writing, Mailer proposed to hire him as a researcher, and with his backing, on June 5, 1981, Abbott was released to a halfway house in New York City.

Now released, and finding himself embraced by the New York literary scene, Abbott nevertheless felt more at ease among the petty criminals of the city’s Lower East Side. A mere six weeks post-parole, Abbott instigated a confrontation with waiter Richard Adan at the Bonibon restaurant, fatally stabbing him in the chest. Fleeing to a small village in Mexico, but his inability to communicate in Spanish hindered him there, so he was forced to return to the United States.

Deciding to return in a different area, he thought that perhaps he could escape detection. Nevertheless, an extensive search ensued, and Abbott was ultimately captured in the Louisiana oil fields after a two-month chase. The manhunt started when he killed Richard Adan at the Binibon restaurant in New York City on July 18 was finally over. At that time of the murder, Abbott was on parole, a privilege granted in part because of author  Norman Mailer’s support of his considerable writing talent, which convinced the authorities. Unfortunately for Adan, the writing skills Abbott had, didn’t do anything to curb his anger.

Norman Mailer’s support of his considerable writing talent, which convinced the authorities. Unfortunately for Adan, the writing skills Abbott had, didn’t do anything to curb his anger.

Incredibly, back in New York, Abbott received the minimum sentence for the murder of Adan. He was sentenced to a mere 15 years to life…partly due to Mailer’s plea for leniency to the court. Mailer believed that “culture is worth a little risk.” I seriously doubt that Adan or his family would agree. As a result of his ability to get off easy, Abbott gained further notoriety, and his book achieved bestseller status. In the end, I suppose one could say that justice was finally served when Abbott took his own life in prison on February 10, 2002.

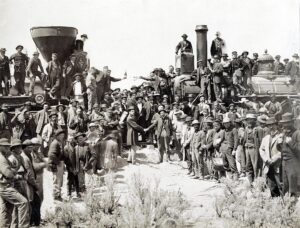

When people started moving west in the United States, the trips took approximately four months by wagon train. At that time, saying “goodbye” to loved ones was a very sad moment, because many times people would never see each other again. The distance was just too great and the cost too much, and unless people were moving permanently, they simply couldn’t take the trip. At that time…the 1860s, they likely had no idea that things would get easier either.

When people started moving west in the United States, the trips took approximately four months by wagon train. At that time, saying “goodbye” to loved ones was a very sad moment, because many times people would never see each other again. The distance was just too great and the cost too much, and unless people were moving permanently, they simply couldn’t take the trip. At that time…the 1860s, they likely had no idea that things would get easier either.

Nevertheless, just a short sixteen years later, all that changed. The train wasn’t a completely new invention in the 1860s, and in fact was invented in 1829. Still, as the United States was experiencing its expansion to the west, there were few towns and no railroads. So, moving west still meant that families might never see their departing loved ones again, and if the did, it would be a number of years. During the early 19th century, when Thomas Jefferson first dreamed of an American nation stretching from “sea to shining sea,” it took the president 10 days to travel the 225 miles from Monticello to Philadelphia via carriage. The distance from New York to San Francisco (which was founded in 1776, but didn’t become part of the United States until the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848). Jefferson was president from 1801 to 1809. The distance from New York City to San Francisco is 2,565 miles from New York City, making the carriage time in those days approximately 114 days, or a little less than a third of a year. If you weren’t moving west, you would also have to make the return trip. It just wasn’t feasible.

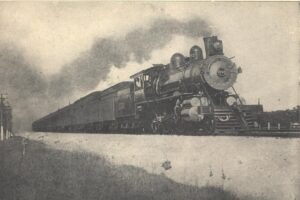

Jefferson saw a possible answer to his dilemma as early as 1802, with “the introduction of so powerful an agent as steam.” At that time, he predicted, the possibility of “a carriage on wheels” that would make “a great change in the situation of man.” For Jefferson, the change would not come soon enough, and he never witnessed the  “carriage on wheels” he had envisioned. Nevertheless, within half a century, America would have more railroads than any other nation in the world, and by 1869, America would see the first transcontinental line linking the coasts was completed. Now, those journeys that were impossible for any reason but moving, that had previously taken months using horses, could be made in less than a week. In fact, on June 4, 1876, the Transcontinental Express train traveled from New York City to San Francisco in a mere 83 hours.

“carriage on wheels” he had envisioned. Nevertheless, within half a century, America would have more railroads than any other nation in the world, and by 1869, America would see the first transcontinental line linking the coasts was completed. Now, those journeys that were impossible for any reason but moving, that had previously taken months using horses, could be made in less than a week. In fact, on June 4, 1876, the Transcontinental Express train traveled from New York City to San Francisco in a mere 83 hours.

It seemed inconceivable that a human being could travel across the entire nation in less than four days. Nevertheless, now the impossible had become not only possible, but a reality, and the United States became a very mobile nation. Prior to that time, the coast were months apart, and it was speculated that the nation couldn’t possibly stay united. They couldn’t even communicate very well, much less see each other. Now, those problems were in the past. Just five days later, daily passenger service began. You simply can’t hold progress back. Once the technology is available, the reality isn’t far behind. Americans were amazed at the speed and comfort of this new form of travel. Of course, it wasn’t for everyone, because as with all new inventions, it was expensive and therefore, only for the wealthy. The train was luxurious, with first-class passengers riding in beautifully appointed cars with plush velvet seats that converted into snug sleeping berths. The finer amenities included steam heat, fresh linen daily and gracious porters who catered to their every whim. For an extra $4 a day, the wealthy traveler could opt to take the weekly Pacific Hotel Express, which offered first-class dining on board. As one happy passenger wrote, “The rarest and richest of all my journeying through life is this three-thousand miles by rail.”

A third-class ticket could be purchased for only $40–less than half the price of the first-class fare. At this low rate, the traveler received no luxuries. Their cars, fitted with rows of narrow wooden benches, were congested,  noisy and uncomfortable. The railroad often attached the coach cars to freight cars that were constantly shunted aside to make way for the express trains. Consequently, the third-class traveler’s journey west might take 10 or more days. Still, no one complained, because 10 days was far better than four months, and sitting on a hard bench seat was still much better than six months walking alongside a Conestoga wagon on the Oregon Trail. Of course, this amazing method of transportation would only be amazing for a short time in history, as trains gave way to cars and eventually airplanes. Still those things were either a way off, or would have to wait for the necessary roads and airports to make those forms of travel available. Trains were here now, and life was good!!

noisy and uncomfortable. The railroad often attached the coach cars to freight cars that were constantly shunted aside to make way for the express trains. Consequently, the third-class traveler’s journey west might take 10 or more days. Still, no one complained, because 10 days was far better than four months, and sitting on a hard bench seat was still much better than six months walking alongside a Conestoga wagon on the Oregon Trail. Of course, this amazing method of transportation would only be amazing for a short time in history, as trains gave way to cars and eventually airplanes. Still those things were either a way off, or would have to wait for the necessary roads and airports to make those forms of travel available. Trains were here now, and life was good!!

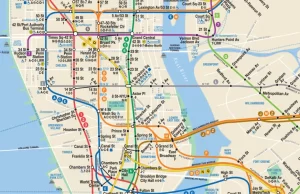

In areas of the country that are more rural, most everyone has their own car, and while we have bus systems, the majority of people drive themselves to do their errands and such. In large metropolis places, like New York City, however, where parking is hard to find, and costs a fortune, many people choose not to own a vehicle. That said, getting around there is not as easy as it is for those of us who simply go out and get in our car, and drive away. For New York City the best solution was to build a subway. As most people know, a subway is a rapid transit system. The one in New York City serves four of the five boroughs of New York City, including the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. The subway is operated by is the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA), which is controlled by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) of New York. In 2016 alone, an average of 5.66 million passengers used the system every day, making it the busiest rapid transit system in the United States and the seventh busiest in the world.

In areas of the country that are more rural, most everyone has their own car, and while we have bus systems, the majority of people drive themselves to do their errands and such. In large metropolis places, like New York City, however, where parking is hard to find, and costs a fortune, many people choose not to own a vehicle. That said, getting around there is not as easy as it is for those of us who simply go out and get in our car, and drive away. For New York City the best solution was to build a subway. As most people know, a subway is a rapid transit system. The one in New York City serves four of the five boroughs of New York City, including the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens. The subway is operated by is the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA), which is controlled by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) of New York. In 2016 alone, an average of 5.66 million passengers used the system every day, making it the busiest rapid transit system in the United States and the seventh busiest in the world.

As New York City grew (it currently has 10 times the amount of people as Wyoming – the smallest state by population), it became obvious that there was going to have to be a public transport system. Work began on  the New York Subway on March 24, 1900, and the first underground line opened on October 27, 1904. The opening of the subway was almost 35 years after the opening of the first elevated line in New York City, which became the IRT Ninth Avenue Line. By the time the first subway opened, the two elevated lines had been consolidated into two privately owned systems, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT, later Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation, BMT) and the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT). All lines built for the IRT and most lines for the BRT were built by the city and leased to the companies after 1913. When the first line of the city-owned and operated Independent Subway System (IND) opened in 1932, it was intended to compete with the private systems and replace some of the elevated railways. The problem was that it was required to be run “at cost,” By necessity, the fares were up to double the five-cent fare, that was popular at the time…thereby, completely defeating the intended purpose.

the New York Subway on March 24, 1900, and the first underground line opened on October 27, 1904. The opening of the subway was almost 35 years after the opening of the first elevated line in New York City, which became the IRT Ninth Avenue Line. By the time the first subway opened, the two elevated lines had been consolidated into two privately owned systems, the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company (BRT, later Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation, BMT) and the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT). All lines built for the IRT and most lines for the BRT were built by the city and leased to the companies after 1913. When the first line of the city-owned and operated Independent Subway System (IND) opened in 1932, it was intended to compete with the private systems and replace some of the elevated railways. The problem was that it was required to be run “at cost,” By necessity, the fares were up to double the five-cent fare, that was popular at the time…thereby, completely defeating the intended purpose.

While the city tried to keep the elevated system running too, and succeeded to a degree, many were had to be closed, because it became too expensive to maintain them. Graffiti, crime, and dilapidation became common. The New York City Subway had to make many service cutbacks and defer necessary maintenance projects just to stay solvent. In the 1980s an $18 billion financing program for the rehabilitation of the subway began. Today, the subway systems remain an important part of the transport system, in New York City. They are also vulnerable to attack, as well as simple maintenance problems. The September 11 attacks prove this without question. The attacks resulted in service disruptions, particularly on the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line, which ran directly underneath the World Trade Center. Several sections were crushed, requiring suspension of  service on that line south of Chambers Street. Work began immediately to repair the damage, and by March 2002, seven of the closed stations had been rebuilt and reopened. All but one of them. Then, on September 15, 2002, that one also reopened with full service along the line. Since the 2000s, expansions include the 7 Subway Extension that opened in September 2015, and the Second Avenue Subway, the first phase of which opened on January 1, 2017. However, at the same time, under-investment in the subway system led to a transit crisis that peaked in 2017. Subways will most likely always be an important part of transportation, especially in big cities. Nevertheless, it will also always have its vulnerabilities.

service on that line south of Chambers Street. Work began immediately to repair the damage, and by March 2002, seven of the closed stations had been rebuilt and reopened. All but one of them. Then, on September 15, 2002, that one also reopened with full service along the line. Since the 2000s, expansions include the 7 Subway Extension that opened in September 2015, and the Second Avenue Subway, the first phase of which opened on January 1, 2017. However, at the same time, under-investment in the subway system led to a transit crisis that peaked in 2017. Subways will most likely always be an important part of transportation, especially in big cities. Nevertheless, it will also always have its vulnerabilities.

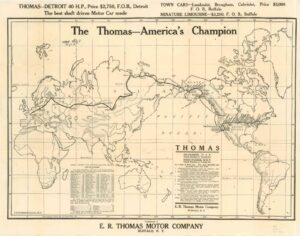

A car race is most often run on a track, with lots of fans cheering everyone on, but in 1908, there was a very strange car race that actually used a track that took the drivers around the world!! How…you might ask?? Well, the car race started in New York City. From there the route took the racers to San Francisco. Normally, San Francisco would be the end of the trail…or the route. You would have reached the Pacific Ocean, and as we all know, cars can’t drive on the ocean…especially cars manufactured in 1908. So, the racers turned to the north and headed for Valdez, Alaska. They would arrive in Valdez in the height of winter…at a time when the Bering Strait was frozen over…theoretically. At that point there was supposed to be an ice bridge across the Bering Strait, making it possible for the cars to drive right over it and into Russia. Once across, the racers would continue on from Russia to Europe and the finish line awaiting them in Paris. It’s amazing to me to think about cars being driven around the world, but of course the Bering Strait in the Winter, supposedly changed everything. In 1908, cars were relatively new, so road infrastructure was limited to only metropolitan areas, and even then, a lot of it was cobbled stone. So, I suppose cross country car travel on dirt trails was not that uncommon.

A car race is most often run on a track, with lots of fans cheering everyone on, but in 1908, there was a very strange car race that actually used a track that took the drivers around the world!! How…you might ask?? Well, the car race started in New York City. From there the route took the racers to San Francisco. Normally, San Francisco would be the end of the trail…or the route. You would have reached the Pacific Ocean, and as we all know, cars can’t drive on the ocean…especially cars manufactured in 1908. So, the racers turned to the north and headed for Valdez, Alaska. They would arrive in Valdez in the height of winter…at a time when the Bering Strait was frozen over…theoretically. At that point there was supposed to be an ice bridge across the Bering Strait, making it possible for the cars to drive right over it and into Russia. Once across, the racers would continue on from Russia to Europe and the finish line awaiting them in Paris. It’s amazing to me to think about cars being driven around the world, but of course the Bering Strait in the Winter, supposedly changed everything. In 1908, cars were relatively new, so road infrastructure was limited to only metropolitan areas, and even then, a lot of it was cobbled stone. So, I suppose cross country car travel on dirt trails was not that uncommon.

The Great Race of 1908 began on February 3rd of that year and immediately ran into challenges. Just to list a few…cars breaking down multiple times, lack of usable roads, car-hating people giving wrong directions, and, oh yeah, SNOW!!! Nevertheless, the teams persevered, and the first team reached San Francisco in 41 days. The came the obstacle of the fact that the proposed route from San Francisco to Alaska did not exist. I guess that they didn’t think it would be feasible to create the route, so the race organizers allowed teams to ship their cars to Valdez, Alaska, then continue on the Ice Bridge. Some might have called that a bit of a cheat, but I guess if all the racers id it, it wasn’t really cheating. Once in Valdez, the teams found out that there is, in fact, no ice bridge across the Bering Strait anymore, because it melted about 20,000 YEARS AGO. Oops…small oversight. So, the racers were allowed to ship their cars across the Pacific to Japan, then Russia, to carry on. Ok, if you’re like me, at this point, you are starting to see that this race had a lot of flaws in the planning. And honestly, while I knew there was no ice bridge on the Bering Strait today, I was unaware that it melted that long ago…meaning there was not an ice bridge since the “Ice Age!!”

So, was this really a car race around the world or a whole lot of non-sense. To be sure, the six teams did end up in Paris after the race, and they drove all of the route that could be driven, but the reality is that much of the race was simply cars being transported by ships across the ocean. Nevertheless, the “official” race was documented as just that…a car race that went around the world. The cars had to fight mud, snow, and mechanical problems. It was “officially” won by The Thomas Flyer, built by the Thomas Motor Company, was a 1907 Model 35 with a 4-cylinder, 60-horsepower engine capable of reaching 60 mph. It was fully loaded with two shovels, two picks, two lanterns, eight searchlights, two extra gas tanks (with a capacity of ten gallons), five hundred feet of rope, a rifle and revolvers. It was also equipped with an attachable top…much like those used on covered wagons…that could wrap the entire car and offer an enclosed place to sleep. On July 30, after 169 days of travel, the Thomas car entered Paris. Even in Paris, they almost didn’t finish, because a police

officer stopped the vehicle, saying it had no working headlight, and couldn’t proceed. A passing bicyclist witnessed the scene and offered to load his bike into the car. Since the bicycle had a working headlight, the officer allowed them to pass. The Thomas Flyer finally finished at 6:00pm. The race was the only “official” car race around the world.

officer stopped the vehicle, saying it had no working headlight, and couldn’t proceed. A passing bicyclist witnessed the scene and offered to load his bike into the car. Since the bicycle had a working headlight, the officer allowed them to pass. The Thomas Flyer finally finished at 6:00pm. The race was the only “official” car race around the world.

New safety laws usually come about as a direct result of a disaster or some other traumatic event. Such was the case with the laws formed after the fire and subsequent sinking of SS Yarmouth Castle. The ship was originally built as Evangeline, and it was an American steamship. It was the second of two identical ships built by the William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Company for the Eastern Steamship Lines for service on the New York City to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia route, operating in practice out of Boston as well. As with many ships, Evangeline was pulled into service during World War II and turned over to the War Shipping Administration, which operated all oceangoing vessels for the United States. During its war years, it was used primarily as an army troop transport. On July 1, 1946, after the war was over, Eastern Steamship Lines resumed control of the ship. Following its war service, it was put back in normal service for a short period and then, the ship was laid up. In 1954, it was sold and put under Liberian registry, operating from Boston to Nova Scotia, then to the Caribbean. In 1963 Evangeline was sold again, put under Panamanian registry. Then, it was renamed SS Yarmouth Castle. It was operated by Yarmouth Cruise Lines between Miami and Nassau, Bahamas, from 1964 until the disaster on November 13, 1965.

New safety laws usually come about as a direct result of a disaster or some other traumatic event. Such was the case with the laws formed after the fire and subsequent sinking of SS Yarmouth Castle. The ship was originally built as Evangeline, and it was an American steamship. It was the second of two identical ships built by the William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Company for the Eastern Steamship Lines for service on the New York City to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia route, operating in practice out of Boston as well. As with many ships, Evangeline was pulled into service during World War II and turned over to the War Shipping Administration, which operated all oceangoing vessels for the United States. During its war years, it was used primarily as an army troop transport. On July 1, 1946, after the war was over, Eastern Steamship Lines resumed control of the ship. Following its war service, it was put back in normal service for a short period and then, the ship was laid up. In 1954, it was sold and put under Liberian registry, operating from Boston to Nova Scotia, then to the Caribbean. In 1963 Evangeline was sold again, put under Panamanian registry. Then, it was renamed SS Yarmouth Castle. It was operated by Yarmouth Cruise Lines between Miami and Nassau, Bahamas, from 1964 until the disaster on November 13, 1965.

On November 12, 1965, Yarmouth Castle departed Miami for Nassau carrying 376 passengers and 176 crew members for a total of 552 people. The ship was due to arrive in Nassau the next day. The captain on the voyage was 35-year-old Byron Voutsinas. Shortly after midnight on November 13, a fire broke out in room 610 on the main deck. Being used as a storage space, the room was filled with mattresses, chairs, and other combustible materials. Unfortunately, the room did not have a sprinkler system, and in the end, the source of the fire could not be determined. It is thought that jury-rigged wiring might have thrown sparks that then entered the room through the ventilation ducts, but simple carelessness was not ruled out either.

A normal patrol went by the room between 12:30am and 12:50am, but they failed to systematically check all areas of the ship and detect the fire. At some point between midnight and 1:00am, the crew and passengers began noticing smoke and heat. Finally, a search was started to find the fire. By the time they discovered it in room 610 and the toilet above that room, it had already begun to spread and attempts to fight the fire with fire extinguishers were useless. Attempts to activate a fire alarm box were also unsuccessful. The bridge was unaware of the fire until about 1:10am, and by that time, Yarmouth Castle was 120 miles east of Miami and 60 miles northwest of Nassau, and in deep trouble. Since the radio room became involved, they were unable to call for help, or even call for the passengers to abandon ship.

The captain proceeded to the lifeboat containing the emergency radio, but he could not reach it. He and several crew members launched another lifeboat and abandoned ship at about 1:45am. The captain later testified that he wanted to reach one of the rescue vessels to make an emergency call. The remaining crew proceeded to alert passengers and attempted to help them escape their cabins. Some passengers tried to escape through cabin windows but couldn’t open them due to improper maintenance. The sprinkler system finally activated but was pretty much ineffective due to the severity of the fire. Crew members attempted to battle the flames with hoses, but they were hampered by low hydrant pressure. The investigation later determined that more valves were open than the pumps could handle.

Some of the lifeboats burned and others could not be launched due to mechanical problems. Only about half of the ship’s boats made it safely away. Passengers near the bow could not reach the lifeboats, but some were later picked up by boats from rescue vessels. The Finnish freighter Finnpulp was just eight miles ahead of Yarmouth Castle, also headed east. That ship’ crew noticed at 1:30am, that Yarmouth Castle had slowed significantly on the radar screen. Looking back, they saw the flames and notified their captain, John Lehto, who had been asleep. Lehto immediately ordered Finnpulp turned around. The Finnpulp successfully contacted the Coast Guard in Miami. It was the first distress call sent out. The passenger liner Bahama Star was following Yarmouth Castle at about twelve miles distance. At 2:15am, Captain Carl Brown noticed rising smoke and a red glow on the water. Realizing that this was Yarmouth Castle, he ordered the ship ahead at full speed. Bahama Star radioed the US Coast Guard at 2:20am.

Though rescue efforts were largely successful, for those who survived, 90 people lost their lives. Yarmouth  Castle capsized onto her port side just before 6:00am and sank at 6:03am. The wreck has not been located but is thought to rest 10,800 feet below the Atlantic. “The Yarmouth Castle disaster prompted updates to the Safety of Life at Sea law, or SOLAS. The updated law brought new maritime safety rules, requiring fire drills, safety inspections, and structural changes to new ships. Under SOLAS, any vessel carrying more than 50 overnight passengers is required to be built entirely of non-combustible materials such as steel. Yarmouth Castle’s largely wooden superstructure was found to be the main cause of the fire’s rapid spread.”

Castle capsized onto her port side just before 6:00am and sank at 6:03am. The wreck has not been located but is thought to rest 10,800 feet below the Atlantic. “The Yarmouth Castle disaster prompted updates to the Safety of Life at Sea law, or SOLAS. The updated law brought new maritime safety rules, requiring fire drills, safety inspections, and structural changes to new ships. Under SOLAS, any vessel carrying more than 50 overnight passengers is required to be built entirely of non-combustible materials such as steel. Yarmouth Castle’s largely wooden superstructure was found to be the main cause of the fire’s rapid spread.”

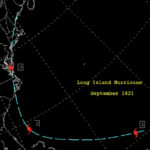

The normal hurricane season is from June 1 to November 30, and since we have our first hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico right now, it looks like it’s right on time. Nevertheless, for places like New York, where it is normally a little cooler, the hurricane season starts a little later, and may not really arrive at all. However, on June 4, 1825, a rare early hurricane arrived, moving off the East Coast and tracking south of New York. The hurricane caused several ship wrecks, and killed seven people.

The normal hurricane season is from June 1 to November 30, and since we have our first hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico right now, it looks like it’s right on time. Nevertheless, for places like New York, where it is normally a little cooler, the hurricane season starts a little later, and may not really arrive at all. However, on June 4, 1825, a rare early hurricane arrived, moving off the East Coast and tracking south of New York. The hurricane caused several ship wrecks, and killed seven people.

The National Hurricane Center, states that on average, hurricane winds have impacted the New York City area every 19 years, and major hurricanes, of a Category 3 or higher, only every 74 years. The highest hurricane reading, Category 5 hurricane is not expected to occur there at all, because of the climate conditions there.

Nevertheless, on June 4, 1825, forming ahead of what is now considered hurricane season, a severe tropical storm surprised the Atlantic seaboard from Florida to New York City. At that time, they did not have the prediction capabilities, and this storm was first sighted near Santo Domingo on May 28th. It moved across Cuba on June 1st, with gale force winds,  beginning at Saint Augustine, and approaching US soil on the June 2nd, and impacting Charleston, North Carolina on June 3rd.

beginning at Saint Augustine, and approaching US soil on the June 2nd, and impacting Charleston, North Carolina on June 3rd.

The tide in North Carolina rose six feet at New Bern and fourteen feet at Adams Creek. As the tide rushed in, more than 25 ships were driven ashore at Ocracoke, 27 near Washington, and also some at New Bern. The plantations on the coastal areas near the South River were inundated with water, causing a heavy loss of crops and livestock. New Bern experienced heavy damage near the waterfront.

The storm pummeled Norfolk, with horrific force for 27 hours as the storm passed by to the east beginning on the  morning of June 3rd. The wind was relentless, uprooting trees as it went. At noon on June 4th, stores on the wharves were flooded in a surge up five feet deep. High winds howled through the Washington DC area. The storm then moved northeast past Nantucket on June 5th.

morning of June 3rd. The wind was relentless, uprooting trees as it went. At noon on June 4th, stores on the wharves were flooded in a surge up five feet deep. High winds howled through the Washington DC area. The storm then moved northeast past Nantucket on June 5th.

The storm reminded many people of the September gale of 1821, except that the September gale would have been much more common. There haven’t been many early June hurricanes in that area since 1825, but there have been a number of hurricanes to hit the area since, including Hurricane Sandy, which did much damage in New York City, including the subway area.

The day after the debut of the Barbi doll on March 9, 1959, at the American Toy Fair in New York City, the doll had become an instant sensation. Basically, her debut makes Barbie 63 years old. The old girl has aged very well. In fact, she hasn’t aged a bit, although she can’t say she hasn’t had any work done. The reality is that Barbie has been redesigned at least every year. Of course, that isn’t saying she has had plastic surgery…or is it? She is, after all, made of plastic.

The day after the debut of the Barbi doll on March 9, 1959, at the American Toy Fair in New York City, the doll had become an instant sensation. Basically, her debut makes Barbie 63 years old. The old girl has aged very well. In fact, she hasn’t aged a bit, although she can’t say she hasn’t had any work done. The reality is that Barbie has been redesigned at least every year. Of course, that isn’t saying she has had plastic surgery…or is it? She is, after all, made of plastic.

Barbie stands eleven inches tall, and at first anyway, had long blond hair. These days, of course as hairstyles have changed and it was decided that not all girls are blonds, her hair color and style have changed with the times. She has been given lots of cool clothes, shoes, a house, car, RV, and boat…and probably many other things. Barbie was the first mass-produced toy doll in the United States with adult features. I suppose that she caused quite a stir with many parents, but for girls everywhere, she was the princess they were going to be when they grew up. I know I couldn’t wait to get one.

The woman behind Barbie was Ruth Handler, who co-founded Mattel, Inc with her husband in 1945. Handler witnessed her young daughter ignore her baby dolls to play make-believe with paper dolls of adult women, at which point she realized there was an important niche in the market for a toy that allowed little girls to imagine the future. Barbie’s appearance was modeled on a doll named Lilli, based on a German comic strip character. Lilli was originally marketed as a racy gag gift to adult men in tobacco shops, but she later became extremely popular with children. Mattel bought the rights to Lilli and made its own version, which Handler named after her daughter, Barbara.

In 1955, Mattel became a sponsor of the “Mickey Mouse Club” TV program. With that, Mattel became one of the first toy companies to broadcast commercials aimed specifically at children. They used their commercials to promote their new toy, and by 1961, the enormous consumer demand for the doll led Mattel to release a boyfriend for Barbie. Handler named him Ken, after her son. Then, Barbie’s best friend, Midge, came out in 1963; her little sister, Skipper, debuted in 1964.

Of course, the Barbie doll was not without controversy. On a positive note, many women saw Barbie as providing an alternative to traditional 1950s gender roles. Her many careers, like airline stewardess, doctor, pilot, astronaut, Olympic athlete, and even US presidential candidate made some women see a possible future that was different

than was common in the 1950s. Others thought Barbie’s never-ending supply of designer outfits, cars, and “Dream Houses” encouraged kids to be materialistic. However, the biggest controversy was over Barbie’s appearance. Her figure was unrealistic for a real woman. It was estimated that if she were a real woman, her measurements would be 36-18-38–led many to claim that Barbie provided little girls with an unrealistic and harmful example and fostered negative body image. Nevertheless, even with the criticism, Barbie never lost her appeal, and in fact she is as popular today as she ever was. I was just 3 years old when Barbie came out, and today, my great granddaughter, Cambree Petersen loves her Barbie dolls as much as I did, even if Barbie is…old!!!

than was common in the 1950s. Others thought Barbie’s never-ending supply of designer outfits, cars, and “Dream Houses” encouraged kids to be materialistic. However, the biggest controversy was over Barbie’s appearance. Her figure was unrealistic for a real woman. It was estimated that if she were a real woman, her measurements would be 36-18-38–led many to claim that Barbie provided little girls with an unrealistic and harmful example and fostered negative body image. Nevertheless, even with the criticism, Barbie never lost her appeal, and in fact she is as popular today as she ever was. I was just 3 years old when Barbie came out, and today, my great granddaughter, Cambree Petersen loves her Barbie dolls as much as I did, even if Barbie is…old!!!

We don’t often think of the United States having castles, but some do exist. Most are not considered true castles, but are rather country houses, follies, or other types of buildings built to give the appearance of a castle. In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but suggesting through its appearance some other purpose, or of such extravagant appearance that it transcends the range of usual garden buildings. Castles seem like almost ancient history items to most of us, and when it came to the United States, many people thought of the Old West and homestead type dwellings. Nevertheless, there are a few real castles here in the United States, even if we don’t have royalty here.

We don’t often think of the United States having castles, but some do exist. Most are not considered true castles, but are rather country houses, follies, or other types of buildings built to give the appearance of a castle. In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but suggesting through its appearance some other purpose, or of such extravagant appearance that it transcends the range of usual garden buildings. Castles seem like almost ancient history items to most of us, and when it came to the United States, many people thought of the Old West and homestead type dwellings. Nevertheless, there are a few real castles here in the United States, even if we don’t have royalty here.

One such castle is Bannerman Castle in New York. The castle is located on Pollepel Island, about 50 miles north of New York City, on the Hudson River. The castle is in serious disrepair, but the Bannerman Castle Trust, Inc is trying to shore up the buildings so they don’t deteriorate further. The analysis that has been done indicates that 5 out of the 7 buildings on the island could be shored up. The others are too far gone. The castle has a strange history, and I suppose some would debate it’s claim as a true castle. The castle was built by Frank Bannerman VI over a period of 17 years. The island’s buildings were personally designed by Bannerman without professional help from architects, engineers, or contractors. The island has buildings, docks, turrets, garden walls, and a moat in the style of old Scottish castles. That was his passion. He loved Scottish castles and built his castle with a Scottish flare. All of the buildings are elaborately decorated, from biblical quotations cast into all fireplace mantles, to a shield between the towers with a coat of arms, and a wreath of thistle leaves and flowers.

Bannerman’s family immigrated to America in 1854, when he was three. They settled in Brooklyn, New York, where his father established a business selling flags, rope, and other articles acquired at Navy auctions. He was a patriotic man, who joined the union army during the Civil War. At that time young Frank began running the business. He was 13 years old. When the Civil War ended, the US government auctioned off military goods by the ton, mostly to be scrapped for their metal. It was young Frank who saw the importance of these materials, and it was his wise purchases that earned him the moniker “Father of the Army-Navy Store.” He could see that much of what was being sold had a market value higher than scrap. Under the guidance of the younger Bannerman, the Bannerman family became the world’s largest buyer of surplus military equipment. By this time, their storeroom and showroom took up a full block at 501 Broadway. Bannerman made his store into a type of museum/store. It opened to the public in 1905. Of it, the New York Herald said, “No museum in the world exceeds it in the number of exhibits.”

Frank was very prosperous, and it was during a business trip to Ireland that he met his future wife, Helen Boyce. They had three children. At the close of the Spanish American War, Frank Bannerman purchased 90

percent of all captured goods in a sealed bid. After that, it became necessary to find a secure place to store their large quantity of very volatile black powder. His son, David saw Pollepel Island, in the Hudson, and Frank Bannerman purchased it in 1900. Following the purchase, the building of the castle began. Today, the island is owned by the state of New York, and at this time visits are prohibited until the buildings can be made safer.

percent of all captured goods in a sealed bid. After that, it became necessary to find a secure place to store their large quantity of very volatile black powder. His son, David saw Pollepel Island, in the Hudson, and Frank Bannerman purchased it in 1900. Following the purchase, the building of the castle began. Today, the island is owned by the state of New York, and at this time visits are prohibited until the buildings can be made safer.