mount everest

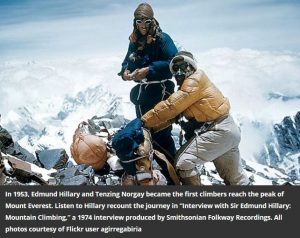

The news of June 2, 1953 was of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, but also of the hailed “good omen” for their country’s future…in reference to the first explorers to reach the summit of Mount Everest, which at 29,035 feet above sea level is the highest point on earth. The landmark assent to the top of the world culminated at 11:30am on May 29, 1953 when Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa of Nepal, made their final assault on the summit after spending a fitful night at 27,900 feet.

The news of June 2, 1953 was of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, but also of the hailed “good omen” for their country’s future…in reference to the first explorers to reach the summit of Mount Everest, which at 29,035 feet above sea level is the highest point on earth. The landmark assent to the top of the world culminated at 11:30am on May 29, 1953 when Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa of Nepal, made their final assault on the summit after spending a fitful night at 27,900 feet.

While the first summit of Mount Everest was an epic accomplishment, it was the words “fitful night” that drew my attention the most. I recently finished a novel by Harry Farthing called “Summit.” While his book was a novel, much of it was based on, if not actual events, actual conditions on the mountain. I am a hiker, and I like hiking to the highest mountains in an area, but let it be known that I am not a mountain climber, and I have no desire to hike through treacherous snow storms to reach the victory of the summit. Nevertheless, many people are obsessed with getting to the world’s highest peaks. Such was the case with Hillary and Norgay. They were determined to make it. I have no idea how prepared they were, but since their victory, and quite possibly before it too, there have been those who misjudged the mountain, the storms, and their own abilities…to their detriment.

While listening to “Summit,” I found myself cheering on the climbers, but also feeling the depths of the many defeats along the way. The biggest necessity on the mountain, is oxygen. At the base camp of Mount Everest, which is 17,500 feet, the air contains 50% of oxygen levels at sea level. At that level, without oxygen, people feel tired and light-headed and develop a headache. They might feel nauseous and even begin to vomit up everything they eat, and then just dry heave themselves to exhaustion. Of course, having oxygen tanks can change this situation into one that is manageable for survival. And that is just at the base camp, which is almost 12,000 feet below the summit. Between Camp 1, at 20,000 feet, and Camp 3, at 24,000 the oxygen levels drop to below 40%. At this point you are prone to hallucinate. Your whole body hurts. You can’t eat, sleep, and most people find breathing next to impossible. From here you operate on sheer willpower. You put one foot in front of the other, and keep moving, because if you do not, you will die. As you near the summit, at 29,035 feet, the air has less that one-third of the sea level oxygen, and can drop as low as 14%…a low level that was recorded in 1996. Twenty climbers lost their fight with the mountain, and their lives, that year. At this point, you should for all intents and purposes be dead. If you are still going, you are probably one of just a few people. On May 8, 1978, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler reached the summit of Mount Everest. They were the first men known to climb it without the use of supplemental oxygen. Two years later, on August 20, 1980, Messner again stood atop the highest mountain in the world, without supplementary oxygen. Cory Richards and Adrian Ballinger also summited the highest mountain in the world in 2017…Ballinger without supplemental oxygen. I don’t know how they did it. Those who have failed to make it to the summit, with or without oxygen, have said that they now know what dying feels like. I’m sure that doesn’t apply to all kinds of death, but certainly death on Mount Everest or any of the other mountains that are nearly as tall, it is like this. The symptoms of death by oxygen depravation quickly take their toll on the body. In the minutes before death, the pain must be excruciating. And then, still before death arrives, the body gives up, and feels no more. The  people that die on Everest are left on Everest. They climbers that go up, pass them along the way. It is a grim reminder that if you are not prepared, you might not be coming down.

people that die on Everest are left on Everest. They climbers that go up, pass them along the way. It is a grim reminder that if you are not prepared, you might not be coming down.

Mount Everest sits on the crest of the Great Himalayas in Asia, lying on the border between Nepal and Tibet. Called Chomo-Lungma, or “Mother Goddess of the Land,” by the Tibetans, the English named the mountain after Sir George Everest, a 19th-century British surveyor of South Asia. It is a majestic mountain, and one I might enjoy seeing…from an airplane…but it is not one that I would ever choose to climb, even though I love to hike. Nevertheless, you can’t help be to be in awe of those who would climb the mountain and receive that treacherous victory.

I love to hike, but that does not include going to the highest peak I can find. Don’t get me wrong, because I have hiked to the top of some mountains. They just weren’t on the level of Everest or K2. While I love to challenge myself by hiking up some pretty big mountains, I’m just not interested in taking on the ones where the air is so thin that you need oxygen, and the snow never melts. There are, nevertheless, people who feel the challenge to ascend to the highest peaks in the world. They throw caution to the wind, to go where few people have ever gone before. Believe me, I admire their tenacity, but that is simply not a goal I have, or ever will set, for myself.

I love to hike, but that does not include going to the highest peak I can find. Don’t get me wrong, because I have hiked to the top of some mountains. They just weren’t on the level of Everest or K2. While I love to challenge myself by hiking up some pretty big mountains, I’m just not interested in taking on the ones where the air is so thin that you need oxygen, and the snow never melts. There are, nevertheless, people who feel the challenge to ascend to the highest peaks in the world. They throw caution to the wind, to go where few people have ever gone before. Believe me, I admire their tenacity, but that is simply not a goal I have, or ever will set, for myself.

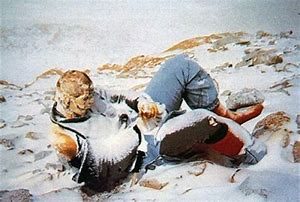

Mount Everest is a very unforgiving mountain. In the years that people have been climbing it, there have been over 200 deaths on it slopes. These were experienced climbers who knew what they were up against, and yet, the elements and the lack of breathable oxygen, beat them in the end. Of those 200+ people who lost their lives to Everest, many are still up on the slopes, right where they fell. They didn’t get off the beaten paths, they just didn’t get back down quickly enough, and now their bodies serve as a grim reminder of the harsh reality that is Everest. These people might have truly believed that they could make it, and many of them had no idea that they were dying. Severe cold and lack of oxygen will do that to a person.

In a gruesome ritual, each new climber who takes the challenge and starts up the mountain, must pass by the unfortunate ones who didn’t make it back down. To me, the bodies would serve as a warning to turn around and go back down, now…to use my head and stay alive, rather than my ambition to succeed at something that, to most of us, seems insane. I know that there are people who would disagree, believing that challenge is worth the risk, and it might be, right up to the point when you realize that you are about to become a statistic of Mount Everest. Of course, by the time you realize that, it is too late.

Mount Everest, located some 186 miles north-east of Kathmandu, holds the impressive title of tallest mountain in the world, but many people don’t know about its other, more gruesome title…the world’s largest open-air graveyard. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay first scaled the summit in 1953. Since then, over 4,000 people have followed in their footsteps, braving the harsh climate and dangerous terrain in the hope of a few moments of glory. Unfortunately, some of them never left the mountain. The top portion of the mountain, roughly everything above 26,000 feet, is known as the “death zone.” In the “death zone” the oxygen levels are only at a third of what they are at sea level, and the barometric pressure causes weight to feel ten times heavier. The combination of those two factors makes climbers feel sluggish, disoriented and fatigued…and can cause extreme stress on organs. For this reason, climbers don’t usually last more than 48 hours in this area.

The climbers that overstay their safety window are usually left with lasting effects. The ones that don’t make it out are left where they fall…it’s standard protocol, unfortunately, and so these corpses remain to spend eternity on the mountaintop, serving as a warning to climbers as well as gruesome mile markers. Each climber who attempts Mount Everest knows the possibilities. One of the most famous corpses, known as “Green Boots” was passed by almost every climber to reach the death zone. The identity of Green Boots while highly contested, is believed to be Tsewang Paljor, an Indian climber who died in 1996. Before the body’s recent removal, Green Boot’s body rested near a cave that all climbers must pass on their way to the peak. The body became a grim landmark used to gauge how close one is to the summit. He is famous for his green boots. According to one seasoned adventurer “about 80% of people also take a rest at the shelter where Green Boots is, and it’s hard  to miss the person lying there.” “Green Boots” is known as such because of the neon boots he was wearing when he died.

to miss the person lying there.” “Green Boots” is known as such because of the neon boots he was wearing when he died.

In 2006 another climber joined in Green Boots in his cave, sitting, arms around his knees in the corner, forever. David Sharp was attempting to summit Everest on his own, which is never advisable. Even the most advanced climbers would warn against it. He had stopped to rest in Green Boots’ cave, as so many had done before him. Over the course of several hours, he froze to death, his body stuck in a huddled position, just feet from one of the most famous Mount Everest bodies. Green Boots most likely died unnoticed, due to the small amount of people hiking at that time, but at least 40 people passed by Sharp that day. Incredibly, not one of them stopped. Sharpe’s death sparked a moral debate about the culture of Everest climbers. Though many had passed by Sharp as he lay dying, and their eyewitness accounts claim he was visibly alive and in distress, no one offered their help. How could they even live with themselves after that?

Sir Edmund Hillary, the first man to ever summit the mountain, criticized the climbers who had passed by Sharp and attributed it to the mind-numbing desire to reach the top. “If you have someone who is in great need and you are still strong and energetic, then you have a duty, really, to give all you can to get the man down and getting to the summit becomes very secondary,” he told the New Zealand Herald, after news of Sharp’s death broke. “I think the whole attitude towards climbing Mount Everest has become rather horrifying,” he added. “The people just want to get to the top. They don’t give a damn for anybody else who may be in distress and it doesn’t impress me at all that they leave someone lying under a rock to die.” The media termed this phenomenon “summit fever,” and it’s happened more times than most people realize.

In 1999, the oldest known body was found on Everest. George Mallory’s body was found 75 years after his 1924 death after an unusually warm spring. Mallory had attempted to be the first person to climb Everest, though he had disappeared before it could be found out if he had achieved his goal.

His body was found in 1999, his upper torso, half of his legs, and his left arm almost perfectly preserved. He was dressed in a tweed suit and surrounded by primitive climbing equipment and heavy oxygen bottles. He had a rope injury around his waist, which led those who found him to believe he had been roped to another climber when he fell from the side of a cliff. The fate of the other climber is unknown, and no one knows if Mallory made it to the top, so the title of “the first man to climb Everest” was given to someone else. Though he may not have made it, rumors of Mallory’s climb had swirled for years, leading many to wonder. He was a famous mountaineer at the time and when asked why he wanted to climb the then unconquered mountain, he famously replied, “Because it’s there.”

One of the most horrifying sights on Mount Everest is the body of Hannelore Schmatz. In 1979, Schmatz became not only the first German citizen to perish on the mountain but also the first woman. Schmatz had actually reached her goal of summiting the mountain, before ultimately succumbing to exhaustion on the way down. Her Sherpa’s warned her not to set up camp in the “death zone,” but she did anyway. She managed to survive a snowstorm hitting overnight, and made it almost the rest of the way down to camp before a lack of oxygen and frostbite resulted in her giving into exhaustion. This poor woman fell just 330 feet from base camp. That is a devastating loss…so close and yet too far. Her body remains on the mountain, extremely well preserved due to the consistently below zero temperatures. For a long time, her body remained in plain view of the mountain’s Southern Route, leaning against a long deteriorated backpack with her eyes open and her hair blowing in the wind. Then, 70-80 mph winds either blew a covering of snow over her or pushed her off the mountain. Her final resting place is currently unknown.

It’s due to the same things that kill these climbers that recovery of their bodies can’t take place. To us that seems insane, but when someone dies on Everest, especially in the death zone, it is almost impossible to retrieve the body. The weather conditions, the terrain, and the lack of oxygen makes it difficult to get to the bodies. Even if they can be found, they are usually stuck to the ground, frozen in place. In fact, two rescuers died while trying to recover Schmatz’s body and countless others have perished while trying to reach the rest. Despite those risks, and the bodies they know they will encounter, thousands of people still flock to Everest every year to attempt one of the most impressive, if not insane, feats known to man today.

It’s due to the same things that kill these climbers that recovery of their bodies can’t take place. To us that seems insane, but when someone dies on Everest, especially in the death zone, it is almost impossible to retrieve the body. The weather conditions, the terrain, and the lack of oxygen makes it difficult to get to the bodies. Even if they can be found, they are usually stuck to the ground, frozen in place. In fact, two rescuers died while trying to recover Schmatz’s body and countless others have perished while trying to reach the rest. Despite those risks, and the bodies they know they will encounter, thousands of people still flock to Everest every year to attempt one of the most impressive, if not insane, feats known to man today.

Recently, I saw an article on an app I have on my phone, called QuakeFeed. It is, of course, an app that tells me when there are earthquakes anywhere in the world, but my settings alert me if they are bigger 5.0. It’s not that earthquakes scare me or even concern me especially, because I don’t live in a really high earthquake area. I’m just naturally curious, and when a quake happens, I go to the map part of the app to see where it was. The app also has stories about the quakes that occur, especially is there was any damage or loss of life. Periodically, I look at the article part of the app, and that was where I saw the article concerning Mount Everest.

Recently, I saw an article on an app I have on my phone, called QuakeFeed. It is, of course, an app that tells me when there are earthquakes anywhere in the world, but my settings alert me if they are bigger 5.0. It’s not that earthquakes scare me or even concern me especially, because I don’t live in a really high earthquake area. I’m just naturally curious, and when a quake happens, I go to the map part of the app to see where it was. The app also has stories about the quakes that occur, especially is there was any damage or loss of life. Periodically, I look at the article part of the app, and that was where I saw the article concerning Mount Everest.

The article talked about an anomaly that I had not considered before. Now, maybe anomaly isn’t really the right word, but in my mind, that’s what it is. It mentioned that there was a possibility that due to earthquakes in the area, Mount Everest might have…shrunk. In case you didn’t know, Mount Everest is located in India and is part of the Himalayan mountain range. Mount Everest sports the crown  as the world’s highest elevation, at 29,028 feet. The next highest elevation in a mountain is K2 in Pakistan. At 28,251 it is a full 777 feet lower than Mount Everest…at last measurement anyway. On April 25, 2015, a 7.8 earthquake hit Nepal at 11:56am, Nepal Standard Time. Known as the Gorkha earthquake, it killed nearly 9,000 people and injured nearly 22,000. Now, the Smithsonian Magazine is reporting that shortly after that quake, Satellite data was used to determine that large swaths of land in Nepal had risen more than 30 feet, while others had dropped. The school of thought is that the possibility exists that Mount Everest has actually shrunk. As I said, to me that seems like an anomaly, but it’s quite possible that Mount Everest, and all the other mountains of the world, have repeatedly changed in altitude. Somehow, I guess I had it in my head that mountain heights are permanent, but that isn’t even logical. The mountains were created by earthquakes. Their size must be subject to change by an earthquake too. It is the only logical conclusion.

as the world’s highest elevation, at 29,028 feet. The next highest elevation in a mountain is K2 in Pakistan. At 28,251 it is a full 777 feet lower than Mount Everest…at last measurement anyway. On April 25, 2015, a 7.8 earthquake hit Nepal at 11:56am, Nepal Standard Time. Known as the Gorkha earthquake, it killed nearly 9,000 people and injured nearly 22,000. Now, the Smithsonian Magazine is reporting that shortly after that quake, Satellite data was used to determine that large swaths of land in Nepal had risen more than 30 feet, while others had dropped. The school of thought is that the possibility exists that Mount Everest has actually shrunk. As I said, to me that seems like an anomaly, but it’s quite possible that Mount Everest, and all the other mountains of the world, have repeatedly changed in altitude. Somehow, I guess I had it in my head that mountain heights are permanent, but that isn’t even logical. The mountains were created by earthquakes. Their size must be subject to change by an earthquake too. It is the only logical conclusion.

The last time Mount Everest was measured was more than six decades ago, so I guess I wasn’t the only one  who thought it wouldn’t change. Nevertheless, now India’s surveyor-general, Dr Swarna Subba Rao has plans to send an expedition to Mount Everest. Their mission is to “re-measure the hulking rock.” They do not expect that Everest has shrunk below 29,000 feet, but the technology has changed on the last 60 years, so it is possible that there might be some discrepancies. These days, scientists will measure Everest’s height using GPS equipment and triangulation techniques. “The observational data would take a month to collect and another 15 days to compute,” said Rao. I for one am excited to hear what their findings are. And, to be honest, I hope that the elevation has changed. To me, that would be like watching history in the making.

who thought it wouldn’t change. Nevertheless, now India’s surveyor-general, Dr Swarna Subba Rao has plans to send an expedition to Mount Everest. Their mission is to “re-measure the hulking rock.” They do not expect that Everest has shrunk below 29,000 feet, but the technology has changed on the last 60 years, so it is possible that there might be some discrepancies. These days, scientists will measure Everest’s height using GPS equipment and triangulation techniques. “The observational data would take a month to collect and another 15 days to compute,” said Rao. I for one am excited to hear what their findings are. And, to be honest, I hope that the elevation has changed. To me, that would be like watching history in the making.