motorized

I don’t know what kind of a city New Orleans was in 1788, but much of it changed that year, because on March 21, 1788, the first of two great fires left the city in ruins. There are a number of ways to destroy a city…time, storms, neglect, need, and the worst one, fire. Were it not for two great fires, there might be more of colonial New Orleans left for people to enjoy. Unfortunately, two great fires in the late eighteenth century left New Orleans and its inhabitants very few years to re-establish their institutions before the onset of American domination in 1803, making the city more American than French. Today, there are several fine houses that date to the last colonial decade, as well as the French Quarter, including the Cabildo and the Presbytere, but they are “post-fire” nevertheless.

I don’t know what kind of a city New Orleans was in 1788, but much of it changed that year, because on March 21, 1788, the first of two great fires left the city in ruins. There are a number of ways to destroy a city…time, storms, neglect, need, and the worst one, fire. Were it not for two great fires, there might be more of colonial New Orleans left for people to enjoy. Unfortunately, two great fires in the late eighteenth century left New Orleans and its inhabitants very few years to re-establish their institutions before the onset of American domination in 1803, making the city more American than French. Today, there are several fine houses that date to the last colonial decade, as well as the French Quarter, including the Cabildo and the Presbytere, but they are “post-fire” nevertheless.

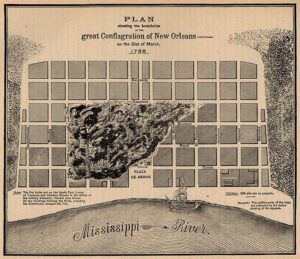

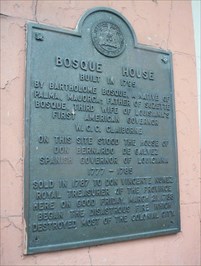

The French Quarter of today is very different from what it once was, and it makes me wonder what it might have been like before. These days, the French Quarter receives millions of visitors annually, and it’s hard to imagine the carnage of the fire of Holy Saturday morning in 1788. The fire was devastating, with smoking ruins stretching from Chartres to Dauphine Street, and from Conti to Saint Philip. The fire actually began on Good Friday morning in the home of Spanish treasurer Don Vincente Nunez at Toulouse and Chartres. The wind was blowing out of the southeast bringing in a blustery cold front. The wind, combined with the fire, reduced over eight hundred homes and public buildings to ashes in a matter of hours. The church, the town hall, and the rectory on the Plaza de Armas were suddenly gone. Governor Esteban Miro told Spanish authorities of the “abject misery, crying, and sobbing” of the people. He wrote that the faces of the families, “told the ruin of a city which in less than five hours has been transformed into an arid and horrible wilderness; the work of seventy years since its foundation.”

The rebuilding of the city began right away, but had barely started when, in 1794 a second fire and two hurricanes swept the city. It seemed that New Orleans was doomed to devastation. The December 8, 1794, fire burned 212 buildings…fewer than the prior fire, but these buildings were more valuable. After the two storms and both fires were done, nearly all the public buildings, homes and businesses, except those fronting the river had been reduced to ashes or badly damaged. Through it all the Ursuline nuns in their convent on Chartres Street had prayed over their hometown, and as the fire got close to the convent on that Good Friday, the wind suddenly shifted. Miraculously, the convent survived and still stands today.

The French Quarter was essentially changed forever. “Baked tile and quarried slate replaced the roofs of ax-hewn cypress shingles. Buildings, set at the sidewalk or banquette, were of all brick, with common firewalls. The wide and shallow hipped roof, galleried townhouse perfected in the French period gave way to vertical, long and narrow Spanish-style town homes, many with overhangs, iron work and entresols or mezzanines. The Cabildo and Presbytere came into being. A new church rose from the ashes. A suburb opened on the upper side of town for residents wary of crowded Quarter conditions. Fire pumps were commissioned. The market moved riverside. Artisans were called in. Protestants gained a foothold. But people went homeless, the city indebted, and lives were lost to death or removal. The city was different.”

Since 1794, the French Quarter has been spared large fires, although there have been some smaller fires, and the hurricanes kept coming. They are just common to the area. A great storm that took place on August 19, 1812, swept away a one-year-old French Market building. Another in 1915 damaged the steeple of Saint Louis Cathedral. A fire in September 1816 took the popular Orleans Theater and Orleans Ballroom. Then, the rebuilt theater burned again in 1866. Fire damaged the Bank of Louisiana on Royal Street resulting in the monumental columns installed in the remodeling, which is now the home of the Vieux Carré Commission.

These devastating losses have resulted in a stringent French Quarter fire code. No longer is the Mardi Gras

parade allowed to be motorized. The city takes prevention very seriously, knowing that fire spreading would be devastating to the French Quarter and to the city as a whole. Even with every precaution, the most important fires of the Twentieth Century occurred at individual structures. It is thought, by some historians, that the burning of the Old French Opera House on Bourbon, in 1919, was the “final nail” in the coffin of the old Creole culture in the Quarter, while others adopted that culture, thereby keeping its memory alive. Then, when the Cabildo burned in 1988, two hundred years after the First Great Fire, the citizens of the city felt the loss deeply. The structure was carefully restored, and it stands as a proud reminder of a city’s resolve to safeguard its heritage to this day.

parade allowed to be motorized. The city takes prevention very seriously, knowing that fire spreading would be devastating to the French Quarter and to the city as a whole. Even with every precaution, the most important fires of the Twentieth Century occurred at individual structures. It is thought, by some historians, that the burning of the Old French Opera House on Bourbon, in 1919, was the “final nail” in the coffin of the old Creole culture in the Quarter, while others adopted that culture, thereby keeping its memory alive. Then, when the Cabildo burned in 1988, two hundred years after the First Great Fire, the citizens of the city felt the loss deeply. The structure was carefully restored, and it stands as a proud reminder of a city’s resolve to safeguard its heritage to this day.

The Spencer ancestry is riddled with names that have been passed down from generation to generation. So much so, in fact, that it can get confusing when researching one’s ancestry. Common names are William, Robert, Thomas, John, Allen, and Christopher. My dad’s family was no different than any other of the Spencer families. The boys in the family were William, named after his grandfather, William, who had a great grandfather named William, and many more I’m sure. My dad was Allen, who was named after his dad Allen, who was named after his grandfather Allen. And many of the children also used those same names, so there were cousins named William and Allen too. Most of the time it only created problems with the ancestry, mail, school things, and such, but when a man named Ethan Allen Spencer (relation, I’m sure, but just how I don’t know) decided that he needed a little bit of excitement in his life, he decided to go from a law-abiding farm family background to becoming a bank and train robber. Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer was born the day after Christmas in 1887 near Lenepah in Nowata County. He came from a law-abiding farm family. He married and soon was the father of a baby girl. So, why would he abandon all that to become a criminal.

The Spencer ancestry is riddled with names that have been passed down from generation to generation. So much so, in fact, that it can get confusing when researching one’s ancestry. Common names are William, Robert, Thomas, John, Allen, and Christopher. My dad’s family was no different than any other of the Spencer families. The boys in the family were William, named after his grandfather, William, who had a great grandfather named William, and many more I’m sure. My dad was Allen, who was named after his dad Allen, who was named after his grandfather Allen. And many of the children also used those same names, so there were cousins named William and Allen too. Most of the time it only created problems with the ancestry, mail, school things, and such, but when a man named Ethan Allen Spencer (relation, I’m sure, but just how I don’t know) decided that he needed a little bit of excitement in his life, he decided to go from a law-abiding farm family background to becoming a bank and train robber. Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer was born the day after Christmas in 1887 near Lenepah in Nowata County. He came from a law-abiding farm family. He married and soon was the father of a baby girl. So, why would he abandon all that to become a criminal.

“Al” Spencer became a criminal as the era of horseback riding was coming to an end, and modern motorized criminals were just getting started. That fact, made Spencer an almost forgotten outlaw. Spencer began his career in crime by getting caught stealing cattle in his early 30s. Then in 1919, he and two men burglarized a clothing store in Neodesha, Kansas. Detectives recovered most of the stolen property and arrested Spencer in La Junta, Colorado. The Kansas court convicted and sentenced him to five years in prison. Then the Oklahoma authorities gained custody of Spencer so they could try him on charges of cattle theft. Spencer pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three to 10 years in the Oklahoma penitentiary at McAlester. He began serving his sentence in March 1920. If you ask me, he should have stuck to farming, because he wasn’t very good at crime. Spencer became friends with another convict named Henry Wells and learned a great deal about crime…becoming better, I suppose…at least as long has Wells was with him. In the 1920s, it was not unusual for Oklahoma governors to grant convicts a leave of absence from prison…even some convicted of major crimes. Spencer was given leave on July 26, 1921, to attend to “some family business” supposedly. He returned to McAlester a month later and became a trustee and was trained to be an electrician. Early in 1922, he was assigned to do electrical work outside the prison in someone’s home. He completed the work, but then he packed up his tools and didn’t return to the prison.

Within a month, Spencer had hooked up with Silas Meigs, who had escaped in a similar fashion from the prison. The pair robbed the American National Bank at Pawhuska, making a “major” haul of $147. Soon the two men robbed a bank at Broken Bow, and this one netted a little more profit. They escaped with between $7,000 and $8,500. They forced a motorist to take them three miles north of town where they had left two horses. The robbers rode away. A few days later Meigs was killed in a gun battle with lawmen northwest of Bartlesville, where he had gone to visit his brother. Spencer remained hidden in the Osage Hills, a vast stretch of country with timber, rocky canyons and thickets of almost impenetrable scrub oak. Friends and relatives brought him food. Spencer later joined up with Henry Wells and two other criminals and robbed a bank at Pineville in  southwest Missouri. Spencer soon hopped a freight train bound for Oklahoma. Spencer found three other men to help him burglarize a store in Ochelata south of Bartlesville. They were surprised by the town’s night marshal who was shot and killed before the outlaws fled in a car. On June 16, Spencer and another man robbed the Elgin State Bank in Chautauqua County, Kansas. They fled with about $2,000 in cash and $20,000 in bonds.

southwest Missouri. Spencer soon hopped a freight train bound for Oklahoma. Spencer found three other men to help him burglarize a store in Ochelata south of Bartlesville. They were surprised by the town’s night marshal who was shot and killed before the outlaws fled in a car. On June 16, Spencer and another man robbed the Elgin State Bank in Chautauqua County, Kansas. They fled with about $2,000 in cash and $20,000 in bonds.

Exactly how many banks were robbed by Ethan Allen “Al” Spencer during the eighteen months following his escape is not known. Evidence suggests he probably robbed at least 20 banks in Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas. The end of his crime spree came on a Saturday evening, September 15, 1923, when he was shot and killed. There is, however, debate on just how he was killed. U.S. Marshal Alva McDonald, a veteran lawman and personal friend of Teddy Roosevelt, claimed he and other lawmen shot Spencer just south of Caney, Kansas. Another account reported that Spencer was killed about five miles north of Coffeyville, Kansas. The third account came from outlaw Henry Wells’ autobiography. Wells claims that Stanley Snyder, a friend of Spencer’s, killed the outlaw with a shotgun while Spencer was eating supper. Some friend he must have been, but then I guess there is no honor among thieves. Al Spencer’s outlaw days were over, nevertheless, and a new breed of bad men soon took his place using only automobiles. Spencer was the last major Oklahoma outlaw to use horses in his crimes.